Paige

Albion Nation

“An Injury to One, is an Injury to All.”

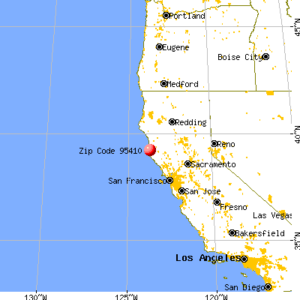

Albion Nation came into existence in 1968; the commune at Table Mountain Ranch became the first of many on Albion Ridge on the Mendocino coast in California (2).

Former Navy pilot Walter Schneider, along with Duncan Ray, bought the 120 acres for $50,000 and invited a few friends to join them. Soon thereafter in the following decade, hundreds moved there, and thousands passed through. This became the Albion nation: “a community of communards and back-to-the-landers, as well as a miscellany of antinomians who made their homes [there]” (2).

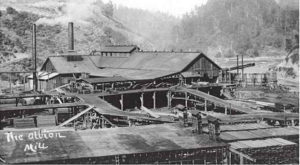

During the 20 years prior to establishment, conquerors and colonizers drove out all inhabitants and cleared the land of its redwoods. Loggers came from eastern parts of America, as well as from Europe and Asia, to profit from the logging industry. This, however, came at a price. Fires incinerated entire ecosystems, specie populations, native plants, and even the dwellings the people themselves had built. “San

Francisco News” reported it as being a ghost town where “no trace of earlier habitations remained […] except […] some blackened ruin, a few rusty chains hanging from a rocky coast […] weather beaten and lichen covered shacks stand gaping open” (2). Despite the recovery efforts, watersheds suffered, and salmon populations decreased exponentially. A revival project seemed near impossible.

By the late 1960s, California had entered its “gypsy years” (which is when Schneider and Ray came into the timeline of it all). In the years to follow, additional communes popped up around Table Mountain Ranch. In 1791, Robert Greenway, Sally Shook, and their seven children settled at Salmon Creek Farm. Carmen Goodyear and Jeannie Tetrault established Thai Farm, the first women’s commune in this area. Albion Nation came to be a group of communes, all with a similar goal in response to the vicious degradation of the Earth that took place, as I mentioned above.

“Our prime commitment is sustainable forestry and the health of the Albion and Salmon Creek watersheds. We are engaged in such environmental issues because as part of local communities and stewardships we believe our struggles are of significance in motion towards a larger goal; that of communities everywhere in contact with the soul of their commons and embracing their local stewardship towards a new/evolutionary social order” (1).

By the mid-’70s, the communards/back-to-the-landers, that is, “‘permanent’ settlers on Albion Ridge may have numbered 500 or more” (2). The living spaces became cramped, and because of this, some of the communes established membership periods in which they ensured the dedication, seriousness, and intention(s) of the potential “member.” They did this because “it was well known that the open communes were already failing. The issues of responsibility and trust were made all the more intense by belief in consensus” (2). This being said, it was certainly not the lifestyle for everyone, as conditions remained primitive: no electricity, no plumbing, no electronics- except for the single vehicle and chainsaw that were shared.

“The Albion communards, so unlike other utopians, past and contemporary, shared no grand vision, no religion, no structures; they were not the followers of a particular leader, there were no gurus. ‘It’s not that we were willfully ignorant; we knew the history of the communal movement. We wanted something different.’ We did not [declare] authority […] We were non-religious, in terms of formal religion, so there were no religious leaders, and we had to develop these systems as gently as we could, without using the techniques that are usually used—the authority of religion and the authority of politics and the authority of money, the power of money’” (2).

However, like many other hippie/communal living groups we’ve discussed, the Albion people wanted to share, cooperate together, live and raise children in common, experiment, explore spontaneity and philosophies, and reject limits. Every action was very much community-focused, a shared responsibility. Because of this, there weren’t any particular individuals who had greater importance within the commune; everyone was more or less equal.

Also similar to that of our notion of a traditional commune, Albion nation had its fair share of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Marijuana and hallucinogens, namely peyote, were quite prevalent in their drug rituals and celebratory events to stay on the sacred path of embracing their spirituality; however, it should be noted that none of these communes sold drugs (mainly because they were anticapitalist).

So… Why did it end? Well in 1980, the counterrevolution was enthroned, and within the communes, “the gap between external change and inner spiritual transformation [seemed] never to have been truly bridged” (2). Concepts of the human condition didn’t just disappear with this lifestyle: jealousy, exclusion/inclusion, general participation, tension and conflict, amongst many others. (Interestingly enough, the more intense disputes occurred on male-female communes, whereas within women’s communes, personal relations were less strained, and arguments were resolved relatively quickly.

The main trouble was the idea that one could merely live simply and ecologically, facing daily the material and cultural scarcity. Desires changed, and as they did, Albion communards began to see the communes as inflexible, confining, and lacking development themselves. They became isolating, rather than accepting, and people began leaving to take on new, flexible lifestyles in various locations across America. Ten years following its establishment, Salmon Creek Farm ended, Trillum 12, and Table Mountain almost 20. (A major flaw of Albion Nation is that it promoted self-connection and stewardship, though there were constraints even to such. If the community had generally been less limiting and restricting, I believe it would have existed much longer.)

By this time, the Albion nation had successfully campaigned against offshore drilling, Japanese whalers, nuclear power, and war; they had succeeded in maintaining focus towards their commitment and making progress. Though it all depends on your own idea of a utopia, I did not see this community as such. I truly cannot see any community as a utopia, especially if we’re aligning our standard/baseline with the fact that everything is “perfect.” Nothing will ever be perfect. We won’t all get along. We won’t all have the exact same ideals, priorities, values, desires. We won’t all be the same people. And that’s okay. What’s important to recognize is not how perfect a specific community is, but rather the issues it specifically addresses as needing improvement, as well as the actions taken in response to such. Albion nation might not have had a Garden of Eden, but it had a garden, and that itself was a step in the direction of the back-to-the land, naturalistic ideology.

***Salmon Creek Farm was purchased by American artist Fritz Haeg in November 2014, and he is currently reviving it as a long-term project. Perhaps the legacy of Albion nation will continue onwards.

Sources:

(1) “Albion Nation.” Albion Nation, Albion Nation, www.albionnation.org/.

(2) Boal, Iain, et al. West Of Eden: Communes and Utopia in Northern California. PM Press, 2012.

(3) Bush, Chuck. “The Albion Nation.” Kelley House Museum, The Kelley House Museum, 10 Sept. 2015, www.kelleyhousemuseum.org/the-albion-nation/.