Why do we read literature?

No, really, why?

Good literature goes beyond entertainment—it reaches down into the core of us and jerks us back into the heart of the world, into the heart of humanity, into the whirling depths of the human soul.

That is what we need to remember.

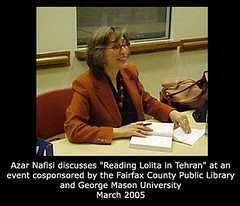

Azar Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Tehran, came to speak at Vanderbilt today, and I had the chance to attend a student-led conversation with her this afternoon.

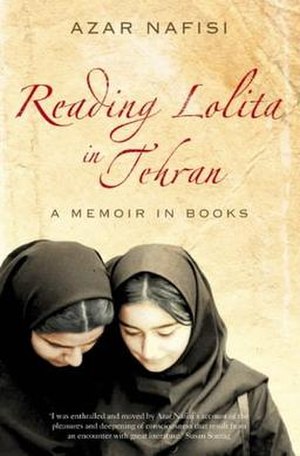

Nafisi’s book, Reading Lolita in Tehran, is the memoir that describes her experiences as a professor of literature under the rule of the Islamic Republic of Iran. After the revolution of 1978, Iran became a place where religion was a forced act of state rather than a personal, spiritual belief. Reacting to these changes—the enforcement of the veil and the brutality of the Taliban—Nafisi used literature, from Nabakov’s Lolita to The Great Gatsby and Huckleberry Finn, to help herself and her female students understand their situations and deal with their own personal traumas.

At the beginning of the conversation, she took out a manila folder of old family pictures and passed them around the conference room. There was her grandmother as a young woman, and there was her mother, and there she was, too. All of them with full lips and black arched eyebrows, none of them wearing the veil except for the grandmother—who thought of it as a personal choice, and was appalled when the government enforced it on all women.

“Imagine,” Nafisi told us, “if suddenly the United States enforced Babtism— a single denomination of a religion—on an entire country, and told you that you—no matter who you were—had to wear a cross around your neck.”

Imagination—it’s a powerful thing. As Nafisi told us today, imagination is what allows us to have empathy. Imagination is what banishes blindness and unwavering ideology. Imagination is the thing that threatens dictatorship and frightens oppression.

And great literature—Lolita, Gatsby, Pride & Prejudice, Huck Finn, and the rest—is the door that allows us to tap into that imagination and those greater human truths.

“That, of course, is what great works of imagination do for us: They make us a little restless, destabilize us, question our preconceived notions and formulas.” – Azar Nafisi

I loved Nafisi’s analysis of the way stories work—the chambers that they open inside us, the thoughts they stir to the surface, the questions they cause us to ask of authority—and specifically of ideological authority.

The past few weeks I’ve been following a blog, Reading the Short Story, by a retired literature professor named Charles E. May. His blog is rather technical, and not altogether engaging unless you are interested in the components of the short story. I read May’s blog because I am interested in the techniques of story, and how these techniques can be applied to my own fiction.

In one of his more interesting posts, though, May writes about C.S. Lewis’ distinction between “good” art and “bad” art, and this distinction is at the heart of what Nafisi differentiates as the narrative of the state vs. the goal of literature.

May writes, “Bad art may be “liked,” but it never “startles, prostrates, and takes captive,” says Lewis. “The patrons of sentimental poetry, bad novels, bad pictures, and merely catchy tunes are usually enjoying precisely what is there. And their enjoyment, as I have argued, is not in any way comparable to the enjoyment that other people derive from good art.”

Good literature—the literature Nafisi read in Iran—allows for complexity.

Good literature—the literature Nafisi read in Iran—allows for complexity.

Too often these days, we’re polarized, shuttled into different “types” of people and frozen into these limited, suffocating identities. White vs. Black, Republican vs. Democrat, Christian vs. Muslim.

In an essay on the illuminating powers of imagination, Nafisi wrote that, “… a culture that has lost its poetry and its soul is a culture that faces death. And death does not always come in the image of totalitarian rulers who belong to distant countries; it lives among us, in different guises, not as enemy but as friend.” –

Good fiction, then, is our escape—an escape route that leads us back into the wonderfully twisted, amorphous human heart.

Where else do we find the ambiguity we so desperately need? The complexity we shy away from, but deep down—so desperately desire?

![]()