To understand abortion, historically, socially, and procedurally, one must first understand the polarizing effects it has. The National Right to Life, America’s oldest and largest pro-life organization, defines abortion as “any premature expulsion of a human fetus” (“Defining Abortion”). At the other side of the spectrum, Planned Parenthood, a nonprofit organization that provides both physical healthcare as well as education on sex and reproductive rights, defines abortion as simply “ending a pregnancy” (“Planned Parenthood”; “Glossary”). The difference in word choice between these two views – pro-life and pro-choice, respectively – represents a larger division that has been present throughout history and that continues to appear in US contemporary society and politics.

Currently, there are many different forms of purposeful abortion, ranging from pharmaceutical to surgical, that each cater to a different stage of prenatal development. However, neither the variety of abortive types nor the accessibility to them has been constant throughout US history. This encyclopedia entry will explore the different biomedical and social issues under the umbrella of “abortion”, provide insight into the politicization of the issue, and analyze the development of the two throughout American history.

Overview and Definitions

The following section outlines the biomedical terminology used to discuss abortion. It should be noted that the commonplace use of the word “abortion” alludes to an induced abortion.

Abortion is classified into two broad categories, natural and induced. A natural abortion can occur either via miscarriage – when an embryo/fetus dies in the uterus before 20 weeks and is then expelled by the body – or via stillbirth – when an infant is delivered at 20 weeks or more without signs of life (L. Palmer and X. Palmer 4). An induced abortion, on the other hand, is categorized into elective, eugenic, or therapeutic. An elective abortion is voluntary and independent of medical justification; a eugenic abortion is undergone on the basis of the undesired qualities of the baby – disability, race, sex, etc.; a therapeutic abortion is one done to save the health and/or livelihood of the mother (L. Palmer and X. Palmer 4).

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, a “professional membership organization dedicated to the improvement of women’s health that produces [OB/GYN] guidelines and other educational material,” there are several distinctions made throughout prenatal development (“About Us”). The broadest distinction is between an “embryo” and a “fetus”. An embryo is a less-developed organism that exists from weeks 3-8 of pregnancy (“Prenatal Development”). A fetus is a more-developed classification and exists from weeks 9-38 of pregnancy, or until the baby is delivered (“Prenatal Development”).

Duration of pregnancy is often divided into three sections, called “trimesters”, which each last around 12-14 weeks (“Prenatal Development”). The first trimester is weeks 1-13, the second is weeks 14-27, and the third varies but is around weeks 28-40 (“Prenatal Development”).

There are other, less regimented points of development at which laws and beliefs were founded upon. “Quickening”, is the point at which a pregnant woman first feels the movements of the embryo/fetus (Brind’Amour, “Quickening”). “Viability” refers to the point at which a fetus has the potential to live outside of the mother’s womb, either with or without artificial aids, and usually occurs around six months of development (Mohr 279).

Abortion: Historical Context

In 17th century England, the legal status of a fetus was not explicitly stated, but, as seen through many cases (one with attempted induced abortion that was concluded as manslaughter), the law leans towards classifying a fetus as a citizen (L. Palmer and X. Palmer 4). This ambiguous scorn of abortion continued across the ocean to the colonies and was not questioned until the 19th century (L. Palmer and X. Palmer 4).

It wasn’t until 1821 that abortion was explicitly mentioned in legislature; then, Connecticut passed a law preventing women from inducing abortion via “poison” after their fourth month of pregnancy (Stern 84). Throughout the rest of the 19th century, anti-abortion/pro-life proponents aimed to illegalize abortion but settled for narrowing the legality to include only therapeutic abortion. Dr. Horatio Storer, one of these proponents, partnered with the American Medical Association to regulate states’ anti-abortion laws in 1856 (Dyer 17). The Comstock Act, passed in 1873, reaffirmed the illegalization of abortion by outlawing access to information about abortion and birth control (Snodgrass 181). This act, which can be found on the Library of Congress’s American Memory website here (under “CHAP CCLVIII”), was wholeheartedly instigated by Anthony Comstock, “chief agent of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV) and postal inspector by congressional appointment” (Tone 435).

The time between the implementation of anti-abortion legislation and the slow overturn of said legislation has been characterized as “birth control’s bleakest chapter” (Tone 437). When looking solely at the legislation and other government documents, this is true. However, as Andrea Tone, a historian and professor of medical history and psychiatry at McGill University, outlines in her article, “Black Market Birth Control: Contraceptive Entrepreneurship and Criminality in the Gilded Age”, this was far from the truth (“Biography”; Tone). In this article, Tone outlines how individuals and groups at each level of society – ranging from the conception providers themselves to the post office and the local and federal judicatures – silently rebelled against Comstock. While the official jurisdiction rendered abortion illegal until the 20th century, the American citizens of the time hardly agreed and acted as such (Tone).

These rumblings of change that occurred before the legalization of abortion in the 20th century were also led by a woman named Margaret Sanger. In 1916, Sanger founded the first birth control clinic in America (“Margaret Sanger – Our Founder” 7). The clinic was located in Brooklyn, New York and had pamphlets with information on how to avoid abortions, available in English, Italian, and Yiddish (“Margaret Sanger – Our Founder” 7). These clinics later became known as Planned Parenthood and began to offer abortions on the first day that New York sanctioned abortion as legal in 1970 (“Margaret Sanger – Our Founder” 12; Greenhouse and Siegel 140). Sanger is often criticized, however, for her support of eugenics – a theory of improving society through purposeful genetic breeding to remove “undesirable” traits (“Margaret Sanger – Our Founder” 7). Claims have frequently been made that she strategically placed clinics in areas heavily populated with blacks and other non-whites (Franks 33). Supporters of Sanger, however, claim that her language and demeanor simply reflected that of the time.

Nevertheless, abortion was still illegal during the majority of the 19th and 20th centuries and was considered a felony in nearly all states by 1967 (Greenhouse and Siegel 121-122). During this decade, President John F. Kennedy established the Presidential Advisory Council on the Status of Women, which called for the repeal of abortion laws (American Women). This national pressure for states to abandon their abortion laws worked; in 1970, New York repealed its previous 19th century ban on abortion and thus legalized abortion “on demand” up to the 24th week of pregnancy (Greenhouse and Siegel 140). Alaska, Hawaii, and Washington soon followed with similar repeals (Greenhouse and Siegel 122).

The following year, the infamous Roe v. Wade Supreme Court case began (Mohr 247). Norma McCorvey, better known as her pseudonym Jane Roe, was a single, pregnant woman in Texas who took action against Henry Wade, the District Attorney of Dallas County to prevent him from enforcing Texas’s “unconstitutional” anti-abortion statute (Mohr 247). Two years later, in 1973, the Supreme Court ruled that these statutes (which existed in most states) were unconstitutional (Mohr 247). The Court also outlined the state’s rights and influential capabilities in the matters of a woman’s desire to abort, which increased each trimester (Mohr 248). The same year, Doe v. Bolton (a “companion case” to Roe v. Wade) was enacted (“Doe v. Bolton (1973)”). Sandra Cano, a married, 9-week pregnant woman filed a court case against Arthur Bolton, Attorney General of Georgia, using the pseudonym of Mary Doe (Zachry 470). She aimed to overturn the unconstitutional Georgia statute that outlawed abortion, except for extreme cases of therapeutic abortion and the Supreme Court ruled in her favor (Zachry 471). One last major Supreme Court case in the 20th century was Bellotti v. Baird. In this 1976 case, the Supreme Court ruled that the Massachusetts Act – which required that any pregnant minor must have parental consent to have an abortion – was unconstitutional, and thus abolished it (Watts 1869-1870). To learn more about the Massachusetts Act and how it, along with the Supreme Court’s converse, affected the abortion rates, read this academic journal: “Parental Consent for Abortion: Impact of the Massachusetts Law”.

By the end of the 20th century, abortion was mostly legalized. While this agreed consensus may appear to be the end of the battle for abortion rights, a closer look reveals that it is not. As with each politically divisive topic, legislation may reflect one side but is completely subject to change at each change of leadership. Such is the case with the current Trump administration. Now, more than ever in the 21st century, there is a strong possibility that the access to abortion may be diminished. President Donald Trump said here that there should be “some form of punishment” for women who undergo abortion (YouTube). Whether or not Trump will act on this statement is hard to discern, as he has gone back and forth on his view of abortion (McKee et al. 750-751). However, Vice President Mike Pence voices a clear pro-life attitude: he has previously supported a bill to “distinguish ‘forcible’ from other types of rape” as well as one to mandate funerals for all fetuses (McKee et al. 751). Pence, as well as the Congressional Republican Party, are “overwhelmingly committed to defunding Planned Parenthood and other reproductive health care providers, reversing the Roe v. Wade decision that [legalized] abortion across the USA, and reducing access to birth control and sex education” (McKee et al. 751).

Abortion Techniques

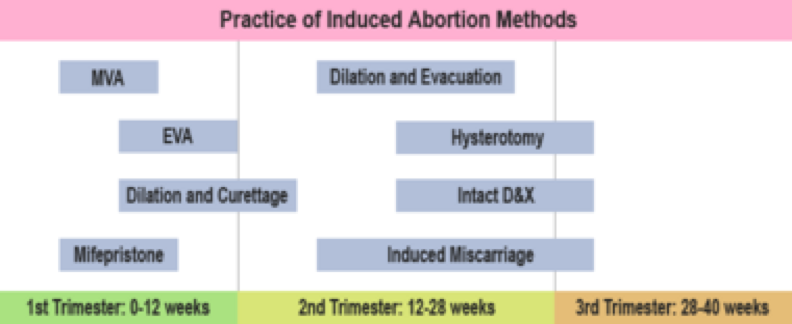

In the actual procedures of induced abortion, there are two main categories: surgical and medical/chemical. The most common form of surgical abortion for the first twelve weeks of gestation is suction-aspiration or vacuum abortion (“Vacuum Aspiration for Abortion”). Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) removes the embryo/fetus via suction of a manual syringe; electric vacuum aspiration (EVA) undergoes the same process but uses an electric pump (“Vacuum Aspiration for Abortion”). The vacuum methods do not require dilation of the cervix but the other two early pregnancy surgical methods, dilation and evacuation (D and E) and dilation and curettage (D and C), do (“US Congressional” 4). D and E involves opening the cervix and emptying it using surgical instruments and suction; D and C is similar, but only involves a curette, which scrapes the walls of the uterus (“US Congressional” 4).

A spoon-like tool, the curette, which is used to clear the uterine walls in the dilation and curettage form of abortion. Found at http://www.innomed.net/hip_tools_curettes.htm.

As the pregnancy develops, abortions become more difficult and invasive. By the third trimester, there are limited options as there is a developed fetus to evacuate. The late development surgical abortions begin with a prostaglandin, which induces premature delivery, and/or an injection to stop the fetal heart (“US Congressional” 5). From there, one can undergo intact dilation and extraction (also called a “partial-birth abortion”) – where the fetus’s head is surgically decompressed and evacuated with forceps – or a hysterotomy abortion – where the fetus is removed via the abdomen, similar to a Caesarian section (“US Congressional” 5).

Within the first 49 days of pregnancy, a woman may choose to undergo the less invasive route of a medical abortion (World Health Organization 8). By pairing the labor-inducing prostaglandin with methotrexate (an immunosuppressive drug), abortion can be induced (World Health Organization 17-18). These drugs are the same ones used for the dilation methods, but early on they can allow for the simple passing of the fetus (“US Congressional” 5).

A chart depicting the different forms of induced abortion as they pertain to each stage of prenatal development. Found at www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Abortion.

There are other, non-regulated, alternative options for inducing labor, many of which were and are used due to legal restriction or inaccessibility to health care. The most common of these include causing trauma to the abdomen, forcefully inserting knitting needles and clothes hangers into the uterus, and consuming potentially life-threatening herbs like tansy and pennyroyal (Gal 105-107). A video demonstrating one of these alternative methods can be found here.

An interesting historical account of a 1970s ‘underground’ abortion service, “Jane”, can be found here. The story provides the techniques of abortion under a historical lens, noting the struggles and successes that the women behind “Jane” encountered (“The Most Remarkable”).

Politicization of Abortion: Pro-Life vs. Pro-Choice

As seen throughout history, there is a strong divide between those who support abortion (“pro-choice”) and those who do not (“pro-life”). Pro-choice activists base their arguments in the belief that the priority of life lies with a woman and she should be able to make choices that impact her own life and body (“Abortion ProCon”). Pro-life activists, on the other hand, focus on the creation of life, often in a religious (usually Christian) context, and argue that it begins at conception, not at birth or viability (“Abortion ProCon”). To further illustrate the opposing viewpoints, take the example of a pregnancy after rape. A pro-choice individual would argue that the woman should exercise her own right to choose whether or not to keep the baby. If she does keep it against her own will, they would say, she may neglect the child and be severely traumatized. A pro-life individual, on the other hand, would argue that she should keep the baby or, at the very least, carry it to term and give it up for adoption. This person would likely say that that baby could be loved by a family who may not have the ability to have a baby of their own, and would stress God’s love for the baby.

It should be noted that the lines between “pro-life” and “pro-choice” are frequently blurred (especially with abortions due to incest and rape). You can find a quiz here that may provide insight into your personal views. Also, there is an account here of a woman who has had an abortion and identifies as both pro-life and pro-choice.

These conflicting views often are the source of many heated debates. They transcend not only to the political debates on reproductive rights, but also to many fields of science. Prenatal genetic testing, for example, is highly controversial, as some pro-life individuals may find it to allow for a eugenic abortion, which may be against their personal beliefs or the beliefs of their religion. Eugene Pergament, a researcher at the Northwestern University Reproductive Genetics center, notes that the semi-recent discovery of the human genome has opened many doors for the world of prenatal screenings (1291-1292). He notes that these tests can screen for individual gene/chromosomal mutations and more recent technology (especially common, non-invasive methods) can detect “a series of genes and gene interactions that impact on different stages of life in both positive and negative manners” (Pergament 1292). To learn more about the different types of genetic testing, visit the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ webpage about it here. More information on one of the most common reasons for aborting after genetic testing, intellectual disability, can be found in this article featured in the National Institute of Health’s archive (Pergament 1295). Lastly, this article from the American Journal of Medical Genetics analyzes the socioeconomic and racial/ethnic factors that contribute to prenatal genetic screening and consequent abortion.

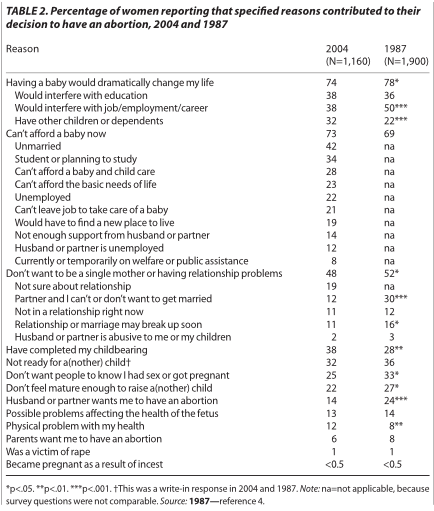

With knowledge of the various diseases and disabilities a baby is at risk for, a parent may choose to abort the baby – either for the benefit of themselves (financial, etc.) or for the benefit of the baby (Pergament 1295). However, there are many other reasons why a woman may choose to have an abortion. In an article written in 1988, Aida Torres and Jacqueline Darroch Forrest shed tremendous light on some of the largest reasons why women have abortions, most of which are still representative of women in the 21st century. These reasons include: wanting to uphold current responsibilities like school or work that a baby would interfere with, lack of maturity to be a parent (especially with teenagers), lack of knowledge of pregnancy, and fear of telling a partner or parent (Torres and Forrest 169). These have withstood throughout history and contemporary reasons for abortion may include the increasingly popular desire for women to be childless but sexually active. Two of the largest, most universally agreed-upon reasons to get an abortion are for incest and rape. Usually, even pro-life individuals claim that abortion is warranted in those cases (but they may prefer the alternative of adoption).

An interesting table showing the difference between attitudes about and reasoning for abortion is shown here (Finer 113).

On the other hand, women may refuse to get an abortion for a variety of reasons. Cultural and religious pressures can play a large role as they may view abortion as “sinful” (Finer 118). It is most frequently moral obligations like these that prohibit a woman from undergoing or even considering an abortion.

An interesting perspective arises when consulting college students on their own perspectives of abortion, especially with the increasing prevalence of the “hookup culture” and commonality of sex. On Vanderbilt’s campus, like most other universities, the loudest voices protest and argue for reproductive rights, including access to abortion. When asked their opinion on abortion, one pro-choice student majoring in MHS and Psychology stated the following:

“I think access to abortion is undeniably a human right. A woman’s body is at her own discretion. If she, for whatever reason, thinks that her bringing a baby into this world would prevent the baby from having the best life possible, she should abort. It makes more sense for a fetus to be subjected to a little (but questionable) pain than for a human to be subjected to a lifetime of pain. It’s not unethical to have a backup plan.”

In contrast, a student who identifies as pro-life and is majoring in Special Education gave this statement:

“I think that everyone should have the right to have an abortion. I think in the case of women getting raped, lacking enough money to afford birth control or support another child, or teen pregnancies, abortions could be justified. While it’s not something I necessarily agree with or would choose to do myself, I can sympathize with others who might need it and don’t think it’s fair to take away the option for anyone to have an abortion by making it illegal.”

The pro-life student’s answer displays more of an “in the middle” stance on abortion, which is very common on more liberal college campuses. While they do agree that abortion should be accessible, they do not agree that eugenic abortions or abortions with social justification are right.

The interplay of pro-life and pro-choice views extends past the realm of college and, especially recently, frequently makes news headlines. On November 27, 2015, Robert Lewis Dear, devout evangelical Christian and pro-lifer, fatally shot and killed three people in a Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood (Hughes). While this was one of the only violent protests, there have been several nonviolent ones, on both sides. The Women’s March on January 21, 2017 protested for reproductive rights, as well as many other rights. As for pro-life protests, there are frequently demonstrations like the one below staged in cities and sometimes near Planned Parenthoods.

Pro-life demonstration by a pro-life group at University of Texas at Arlington that was met with backlash. Found at http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/apr/3/pro-life-display-featuring-crosses-faces-backlash-/.

This encyclopedia entry only references US abortion tendencies. For a global perspective on induced abortion, read this article.

Abortion and Politics of Health

This topic relates to politics of health because it quite literally embodies how politicized health can become. The opinions on abortion, for and against, permeate into the political sphere and into legislature. This can be seen throughout the entire history of abortion in the United States. More specifically, abortion relates to politics of health through its connection to medicalization and pharmaceuticalization.

Medicalization, as Peter Conrad outlines, refers to the “creation of new medical categories with subsequent expansion of medical jurisdiction” (3). Induced abortion has been medicalized throughout the course of history, as seen through the creation of multiple surgical procedures, medicinal treatments, and clinics solely for abortion. The government and its legislature have a strong influence on this change, as the legalization of abortion allowed for a demand of abortive products and services. It will be interesting to analyze if abortion is illegalized in the future, as the de-medicalization of the abortion industry would have a tremendous impact.

Similarly, the increasing prevalence of medical abortions is an example of pharmaceuticalization. Social scientists Simon Williams, Paul Martin and Jonathan Gabe define the term as “the translation or transformation of human conditions, capabilities, and capacities into opportunities for pharmaceutical intervention” (Williams et al. 711). As noted earlier in the entry, abortion has not always been pharmaceutical – whether it be due to social, legislative, or socioeconomic restraints. In our contemporary society, however the appeal for medical abortions is clear: “low costs”, “low requirements for inpatient care” due to complications, no anesthesia, “less invasive and more ‘natural” (Ashok et al. 2964; Henshaw 715). Back-up contraceptives (meant for the morning after unprotected sex) like “Plan B One Step” have also contributed to the pharmaceuticalization of abortion.

Bibliography

“Abortion ProCon” ProConorg Headlines, abortion.procon.org/.

“About Us.” About Us – ACOG, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, www.acog.org/About-ACOG/About-Us.

American Women: Report of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women. Govt. Pr., 1963.

Ashok, P. W., et al. “An effective regimen for early medical abortion: a report of 2000 consecutive cases.” Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 13.10 (1998): 2962-2965.

“Biography.” Dr. Andrea Tone | Social Studies of Medicine, McGill University, www.mcgill.ca/ssom/staff/tone.

Brind’Amour, Katherine, “Quickening”. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2007-10-30). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1717.

Conrad, Peter. “The Shifting Engines of Medicalization∗.” Journal of health and social behavior 46.1 (2005): 3-14.

“Defining Abortion.” Abortion Techniques, National Right to Life, www.nrlc.org/archive/abortion/facts/abortiontimeline.html.

“Doe v. Bolton (1973).” Doe v. Bolton, End Roe, www.endroe.org/doe-v-bolton.aspx.

Dyer, Frederick N. “Horatio Robinson Storer, MD and the Physicians’ Crusade Against Abortion.” Life and Learning 9 (1999): 2.

Finer, L. B., Frohwirth, L. F., Dauphinee, L. A., Singh, S. and Moore, A. M. (2005), Reasons U.S. Women Have Abortions: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37: 110–118. doi:10.1111/j.1931-2393.2005.tb00045.x

Franks, Angela. Margaret Sanger’s Eugenic Legacy: the Control of Female Fertility. McFarland & Co, Inc., 2005.

“Glossary of Sexual Health Terms.” Planned Parenthood, Planned Parenthood Federation of America, www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/glossary.

Greenhouse, Linda, and Reva B. Siegel. Before Roe v. Wade: Voices That Shaped the Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court’s Ruling. Kaplan, 2010.

Gul, Somia, et al. “Herbal drugs for abortion may prove as better option in terms of safety, cost & privacy.” Journal of Scientific and Innovative Research 4.2 (2015): 105-108.

Henshaw, R. C., et al. “Comparison of medical abortion with surgical vacuum aspiration: women’s preferences and acceptability of treatment.” Bmj 307.6906 (1993): 714-717.

Hughes, Trevor. “Planned Parenthood Shooter ‘Happy’ with His Attack.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 12 Apr. 2016,www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/04/11/planned-parenthood-shooter-happy-his-attack/32579921/.

“Large Bone Curettes.” Innomed Orthopedic Instruments, http://www.innomed.net/hip_tools_curettes.htm.

“Margaret Sanger – Our Founder.” www.plannedparenthood.org/files/9214/7612/8734/Sanger_Fact_Sheet_Oct_2016.pdf.

McKee, Martin, Scott L Greer, David Stuckler, What will Donald Trump’s presidency mean for health? A scorecard, In The Lancet, Volume 389, Issue 10070, 2017, Pages 748-754, ISSN 0140-6736, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30122-8. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673617301228)

Mohr, James C. Abortion in America: The origins and evolution of national policy. Oxford University Press, 1979.

Palmer, Louis J., Jr., and Xueyan Z. Palmer. Encyclopedia of Abortion in the United States, McFarland & Company, Incorporated Publishers, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/vand/detail.action?docID=1593739.

Pergament, Eugene. “The future of prenatal diagnosis and screening.” Journal of clinical medicine 3.4 (2014): 1291-1301.

“Prenatal Development: How Your Baby Grows During Pregnancy.” Prenatal Development, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, June 2015, www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Prenatal-Development-How-Your-Baby-Grows-During-Pregnancy.

“Planned Parenthood at a Glance.” Planned Parenthood, Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc., www.plannedparenthood.org/about-us/who-we-are/planned-parenthood-at-a-glance.

Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. The Civil War Era and Reconstruction: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History. Routledge, 2015.

Stern, Loren G., Abortion: Reform and the Law, 59 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 84 (1968)

Tanabe, Jennifer. “Abortion Methods.” New World Encyclopedia, 15 May 2007, www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Abortion.

“The Most Remarkable Abortion Story Ever Told.” The Most Remarkable Abortion Story Ever Told, The CWLU Herstory Website, http://webtraxstudio.pairserver.com/cwluherstory/CWLUFeature/Remarkable1.html

Tone, Andrea. “Black Market Birth Control: Contraceptive Enterpreneurship and Criminality in the Gilded Age.” The Journal of American History, vol. 87, no. 2, 2000, pp. 435–459. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2568759.

Torres, Aida, and Jacqueline Darroch Forrest. “Why Do Women Have Abortions?” Family Planning Perspectives, vol. 20, no. 4, 1988, pp. 169–176. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2135792.

U.S. Congressional Research Service. Abortion Procedures (95-1101 SPR; Oct. 8, 1998), by Irene E. Stith-Coleman. Text in: ProQuest® Congressional Research Digital Collection; Accessed: October 12, 2017.

“Vacuum Aspiration for Abortion.” WebMD, WebMD, www.webmd.com/women/manual-and-vacuum-aspiration-for-abortion.

Watts, William W. “Parent, Child, and the Decision to Abort: A Critique of the Supreme Court’s Statutory Proposal in Bellotti v. Baird.” Southern California Law Review 52.6 (1979): 1869-1916.

Williams, Simon J., Paul Martin, and Jonathan Gabe. “The pharmaceuticalisation of society? A framework for analysis.” Sociology of Health & Illness 33.5 (2011): 710-725.

World Health Organization. Frequently Asked Clinical Questions about Medical Abortion : Conclusions of an International Consensus Conference on Medical Abortion in Early First Trimester, Bellagio, Italy, World Health Organization, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/lib/Vand/detail.action?docID=286835.

YouTube. TMP TV, 30 Mar. 2016. Web. 13 Oct. 2017. <https://youtu.be/sQfJpTUYr2Q>.

Zachry, H. Cam. “The Abortion Decisions: Roe v. Wade, Doe v. Bolton.” Journal of Family Law 12.3 (1972): 459-480.

« Back to Glossary Index