Definition

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine where certain points on the body are stimulated by inserting and manipulating special needles. Acupuncture literally means “to puncture with a needle,” which comes from the Latin words acus (needle) and punctura (puncture) (Lewith). The practice originated in China thousands of years ago as an ancient medical technique for “relieving pain, curing disease, and improving general health” (“Acupuncture”). Acupuncture is based on the traditional Chinese concepts of “qi,” “yin,” and “yang,” which represent dynamic energy, forces of life, and connections between the natural world and the human body (Kung). The actual process of acupuncture consists of placing needles into hundreds of possible points on the body based on diagrams and models, depending on the area of pain. Typically, needles are inserted 0.1 to 0.4 inches in depth, while some procedures call for 10 inches (“Acupuncture”). After the needles are inserted, they may be twisted and turned to create nerve stimulation and release endorphins.

Historical Context

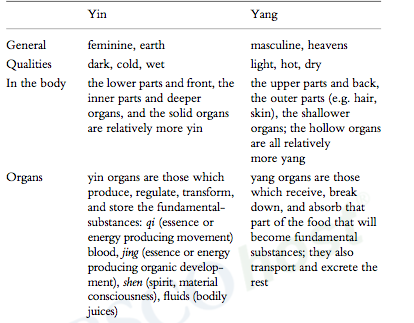

Although acupuncture began as a form of traditional Chinese medicine, it eventually spread and influenced other areas of the world. Acupuncture was created before 2500 BCE and was based on Chinese philosophies like the yin, the yang, and the qi (“Acupuncture”). The yin is known as the feminine and earthly force with general qualities being dark, cold, and wet. The yang is known as the masculine and heavenly force with general qualities being light, hot, and dry (Bivens). Because traditional Chinese medicine focused more on the physiology of the body, as opposed to the physical structure, certain organs were related to the forces of yin and yang and treatments were determined based on the symptoms and body parts as shown in the chart below (Bivens).

Image: Shows the differences between the yin and yang and their effects on the human body (Bivens).

The goal of traditional Chinese medicine is to have the forces of the yin and the yang balanced. Therefore, these forces act similarly in the human body as they do in the natural universe. For example, disease causes an imbalance in the human body, but Chinese medicine attempts to bring harmony and restore the human to health (“Acupuncture”). In addition to the forces of yin and yang, the qi is a life force that is based off of twelve pathways in the human body which are associated with a major organ and function. Organs, tissues, veins, and nerves are all connected through this energy network (“Traditional”). Ultimately, traditional Chinese doctors believed that when needles are inserted into specific pathway points of the body, the flow of the qi will be readjusted and the yin and yang will be balanced (“Traditional”).

Acupuncture became well known throughout the United States in 1971 when a reporter accompanying President Nixon in China, James Reston, received relief after an appendectomy surgery by the means of acupuncture (Ulett). His experience was reported in the media and created enthusiasm in the public, but physicians were hesitant to practice acupuncture due to the lack of scientific basis (Ulett). Retson’s experience sparked interest and research among the medical community. Eventually, it was discovered that acupuncture’s needling technique may be responsible for releasing endorphins in the brain (Ernst). Since then, scientific research has led to NIH’s conclusion in 1973 that “acupuncture holds some promise as an anaesthetic for certain surgical operations and for the treatment of some acute and chronic painful conditions” (Ulett). The historical context of acupuncture is based on traditional Chinese medicine, as opposed to science. The practice of acupuncture existed first, and eventually the limited scientific evidence followed.

Perspectives

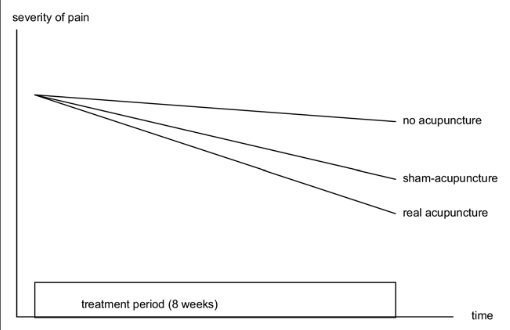

Even though acupuncture is widely practiced in the United States, it is not entirely understood nor supported. Supporters of acupuncture claim that the practice is not only effective, but it also has fewer adverse side effects compared to other common Western medical treatments like drugs or medical procedures (National Institutes of Health). Many studies have shown that acupuncture can cause biological responses in humans and animals which occur either at the site of stimulation, or at a distance away from the site through sensory neurons in the central nervous system (National Institutes of Health). Ultimately, this can lead to physiological systems in the brain to be effected as well. It has been documented that stimulation through acupuncture has a role in releasing endorphins, “natural painkillers,” into the bloodstream (Dupler). In fact in 2008, acupuncture was practiced in all U.S. 50 states and 15 million Americans have used it as therapy due to its reputation of being effective (Dupler). In a randomized control trial studying the effect of acupuncture on chronic pain, no acupuncture, “sham” acupuncture, and real acupuncture were used as independent variables. Sham acupuncture uses needling at nonacupuncture points, but real acupuncture is the authentic treatment. As shown in the image, sham acupuncture still is more effective in reducing pain than no acupuncture. Therefore, acupuncture enthusiasts believe that any kind of acupuncture is clearly better than none at all (Ernst).

Image: The severity of chronic pain based on the designated treatment for 8 weeks (Ernst).

The uncertainty of the medical world is mostly based off of the lack of science behind the traditional Chinese medicine practice. Supporters are dedicated to prove that acupuncture continues to show levels of effectiveness in clinical tests, despite the ambiguity of the specific biochemisty involved (Dupler).

On the other hand, critics of acupuncture rely heavily on the argument that the practice itself is simply a placebo effect. The ambiguity of the true biochemical effects, along with the ambiguity of points in which to place the needles, leads to doubt among skeptics. Treatment is applied to acupuncture points and “originally there were 365 such points, corresponding to the days of the year, but the number identified by proponents during the past 2,000 years has increased gradually to about 2,000” (Barrett). Critics of acupuncture also emphasize the fact that patients may experience positive results because they expect positive results, which is a part of the placebo effect. Even in “fake” or “sham” acupuncture procedures, patients claim to experience benefits and relief. This relief is less than “real” acupuncture, but more than no treatment at all. In fact, “a treatment that generates only nonspecific effects (for conditions that are amendable to specific treatments) cannot be categorized as truly effective or useful” (Ernst). Therefore, some critics believe that acupuncture, as a placebo, “works” because practitioners present it as a treatment, and the patients trust the practitioner doing it (Ernst).

Politics of Health

Acupuncture is related to politics of health because it is a form of alternative medicine that has been involved in the discussion of differences between alternative medicine and conventional medicine. The controversy over whether acupuncture is effective and has real scientific benefits, or whether it is the embodiment of the placebo effect, contributes to the discussion of alternative medicine and conventional medicine. Alternative medicine is normally used in place of conventional medicine, like medical drugs and surgeries. It is considered alternative because it is based on ideas about health that differ dramatically from the regular medical community (Clow). This phrase first emerged in the 1960s and 1970s when an increasing amount of patients either turned away from conventional care or became interested in natural healing (Clow). In the previous decades, acupuncture was clearly defined as a form of alternative medicine as a result of its background from traditional Chinese medicine, but its increasing popularity and scientific base could contribute to its integration into conventional medicine and medical orthodoxy.

Works Cited

“Acupuncture.” Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 Apr. 2016. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/acupuncture/3626. Accessed 15 Nov. 2017.

Barrett, Stephen. “The Effectiveness of Acupuncture Has Not Been Proven.” Medicine, edited by Laura K. Egendorf, Greenhaven Press, 2003. Opposing Viewpoints. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/EJ3010302215/OVIC? u=nash87800&xid=a781d357. Accessed 19 Nov. 2017. Originally published as “Acupuncture, Qigong, and ‘Chinese Medicine,’,” Quackwatch, 2 Sept. 2001.

Bivins, Roberta E. Alternative Medicine? : a History. OUP Oxford, 2010. EBSCOhost, proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx? direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=381035&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Clow, Barbara. “alternative medicine.” The Oxford Companion to Canadian History. : Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference. 2004. Date Accessed 19 Nov. 2017 <http://www.oxfordreference.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/view/10.1093/acref/ 9780195415599.001.0001/acref-9780195415599-e-56>.

“Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).” Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 6 Apr. 2017. academic.eb.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/levels/collegiate/ article/complementary-and-alternative-medicine/604955. Accessed 19 Nov. 2017.

Dupler, Douglas, et al. “Acupuncture Is Suitable for Treating a Wide Range of Conditions.” Alternative Therapies, edited by Sylvia Engdahl, Greenhaven Press, 2012. Current Controversies. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/ EJ3010562243/OVIC?u=nash87800&xid=fcdc6924. Accessed 19 Nov. 2017. Originally published as “Acupuncture,” Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine, , p. 3E.

Ernst, Edzard. “The Recent History of Acupuncture.” Vanderbilt Library, ScienceDirect, Dec. 2008, www.sciencedirect.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/science/article/pii/ S0002934308005688?via%3Dihub.

Kung, Christine C. “Defining a Standard of Care in the Practice of Acupuncture.” American Journal of Law and Medicine 31.1 (2005): 117-30. ProQuest. Web. 16 Nov. 2017.

Lewith, George. “acupuncture.” The Oxford Companion to Medicine. : Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference. 2006. Date Accessed 15 Nov. 2017 <http:// www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192629500.001.0001/acref-9780192629500-e-7>.

National Institutes of Health. “Acupuncture Is a Useful Treatment.” Medicine, edited by Laura K. Egendorf, Greenhaven Press, 2003. Opposing Viewpoints. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/EJ3010302214/OVIC?u=nash87800&xid=4b1a7e6d. Accessed 19 Nov. 2017. Originally published as “Acupuncture,” National Institutes of Health consensus statement, 40607 Nov. 1997.

“Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).” Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 20 Oct.2017. academic.eb.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/levels/collegiate/article/traditional-Chinese-medicine/474446. Accessed 18 Nov. 2017.

« Back to Glossary Index