Overview

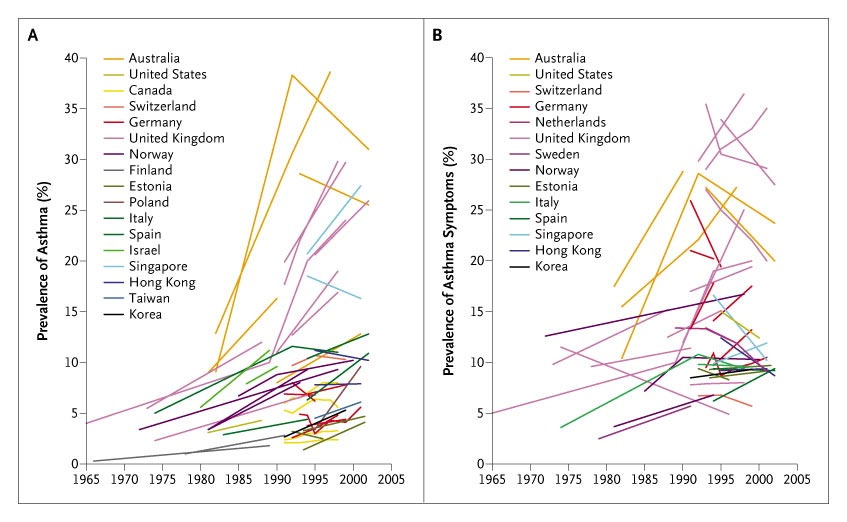

Asthma is recognized today as one of the most prevalent chronic illnesses affecting children worldwide (Bialostozky & Barkin, 2012). Rates of diagnosis and treatment efforts continue to increase as asthma significantly contributes to hospitalizations in children younger than 15 years old (Pepper & Schwartz, 2009). This trend is especially true among inner-city residents and minority groups in the United States as well as in other rapidly developing countries as can be seen in the figure below (Bialostozky & Barkin, 2012; Whitmarsh, 2010).

(Eder, Edge, & von Mutius, 2006)

(Eder, Edge, & von Mutius, 2006)

As epidemiologists and other medical practitioners seek to better understand the prevalence of asthma, various hypotheses have been proposed in an attempt to pinpoint the singular driving factor of the disease (Whitmarsh, 2010).

A doctor is seen auscultating a young patient’s lung sounds in a primary school screening for asthma. Asthma is recognized today as one of the most prevalent chronic illnesses affecting children worldwide. This trend is especially true among inner-city residents and minority groups in the United States as well as in other rapidly developing countries (Bialostozky & Barkin, 2012; Whitmarsh, 2010)

(AP Photo/Carolos Osorio)

Medical Definition

Asthma is characterized by the “narrowing of airways” and irritation of the walls of the lungs leading to inflammation (Rees, 2001). This irritation and inflammation can be further aggravated by smooth muscle contraction and increased narrowing of the airway due to external stimuli like dust, smoke, or increased respiration and drying of the airway during exercise (Rees, 2001). Symptoms of an asthma attack include shortness of breath, wheezing, and coughing as the membranes in the lining of the airways may secrete high levels of mucus (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], National Institutes of Health [NIH], National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2014).

The image below shows cross-sectional images of a normal airway (B) and one during an asthma attack (C) (HHS, NIH, NHBLI, 2014).

Medical practitioners recognize asthma as a treatable and reversible condition through the use of medications such as inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta agonists (Brookes, 1994; Lemanske & Busse, 2003). Inhaled corticosteroids are administered using an inhaler and spacer in order to reduce inflammation, swelling, and mucus production in an individual’s airway (HHS, NIH, NHBLI, 2014). Some patients may use long-acting beta agonists in conjunction with inhaled corticosteroids, but never alone, to further relax the muscles in an individual’s airways (HHS, NIH, NHBLI, 2014).

History of Asthma

The term ‘asthma’ first appeared in the works of Homer nearly 3000 years ago and comes from the Greek word for panting (Jackson, 2009). Physicians from ancient Greece: Hippocrates, Areteaus, and Galen were among the first to describe the medical condition; but it wasn’t until Laënnec invented the stethoscope in the early 19th century, that wheezing sounds in the lungs were associated with the disease (Rees, 2001). Halfway through the century, physicians proposed that asthma had a root cause, but could not agree whether it was “a disease of the nervous system, or the lungs, or the blood” (Whitmarsh, 2010, p.1). The use of microscopes and respirometers later in the century led to the categorization of asthma as nervous asthma (no pathological lesions) or allergic asthma (no germs associated) (Whitmarsh, 2010, p.1). Towards the end of the 19th century, British and American research described asthma as “neurosis or physiological predisposition; caused by dust, pollution, heredity, parental emotions, the unclean modern home, or the continually cleaned modern home,” contributing to the rise of the allergic approach and the hygiene hypothesis (Whitmarsh, 2010, p.1). The hygiene hypothesis proposes that children today are oversensitized to allergens due to a lack of exposure to infections and bacteria in the modern home, and are therefore more likely to develop asthma (Whitmarsh, 2010, p.1).

Those arguing in favor of the hygiene hypothesis might present evidence from the effects of parental smoking on their child’s asthma outcomes in order to demonstrate the direct environmental effect within the home. A study by Weitzman, Gortmaker, Klein, and Sobol (1990) found that maternal smoking is “associated with higher rates of asthma, an increased likelihood of using asthma medications, and an earlier onset of the disease” (p. 508). This study is one of many cited by pediatricians in order to convince parents of the negative effects of smoking and similar messages have appeared in television campaigns in order to communicate the negative effects of second-hand smoke (Metzl, 2010). These messages are all argued in the name of a child’s health, and are defended as noble causes. However, Metzl suggests that “’health’ is a term replete with value judgments, hierarchies, and blind assumptions” that allows for “moral assumptions” to be made where they otherwise would not have been made (2010, p.1-2). From his moralizing perspective, we should not use the term health to define bad parenting and condemn smokers for subjecting their children to secondhand smoke.

Multidisciplinary Approach and Connections to Politics of Health

Rates of diagnosis and treatment have significantly increased in both children and adults throughout the world, contributing to the push for research across domains and an expanding market for treatment options (Masoli, Fabian, Hold, & Beasley, 2004).

Studies on population demographics within the United States have revealed that inner-city children have among the highest rates of asthma (around 30%) and that asthma is experienced differently across ethnic groups (Warman, Silver, & Stein, 2001). Specifically, research has found that African Americans have a higher morbidity rate, mortality rate, and prevalence of asthma than Caucasians (Whitmarsh, 2008, p. 5). To better understand this prevalence, biomedical professionals have explored asthma through genetic propensities and the biological basis of race. Specifically, pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries study responses to medication based on the genetic differences of race (Whitmarsh, 2008, p. 5).

However, this type of research is highly critiqued and controversial in the United States as scientists disagree on the existence of a biological basis of race as genomic research has revealed a “greater genetic variation within groups than between them” (Reardon, 2005, p. 35). Additionally, previous research on race and disease in the United States resulted in tension and mistrust in African American populations. This is especially true in the case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Johns Hopkins’ difficult relationships with Baltimore neighborhoods (Boger, 2009). Therefore, the pressure to understand the prevalence of asthma in African American populations led to the internationalization of this race-disease research.

An example of this internationalized research is Johns Hopkins’ Barbados Asthma Genetics Study that began in 1993, involving a research team of geneticists, epidemiologists, and clinicians. Barbados was selected as the site for the study due to the fact that 18-20% of the population suffers from asthma and that 92% of the population is cited as black (Whitmarsh, 2008, p. 7). In this study, researchers “conducted home visits in which study facilitators took blood samples, administere[ed] an asthma questionnaire, collect[ed] dust samples, and conduct[ed] spirometry” (Whitmarsh, 2008, p. 7). The respirometer/spirometer is a pulmonary function test used to measure lung capacity. However, Hutchinson’s (1840) respirometer was adopted by Cartwright, a slaveholder in the United States, to prove Jefferson’s theory that there were physical distinctions between the lungs of slaves and white colonists. Respirometers used today still practice “race correction” or “ethnic adjustment” by either “using a scaling factor for all people not considered to be ‘white’; or by applying population-specific norms” (Braun, 2015). Medical professionals must manually select the race of the patient before applying the test, unconsciously fostering the idea of a biological basis for race. The issue with using spirometers that correct for race in diagnosing asthma, fails to consider all the environmental factors that can contribute to the development of asthma.

This image depicts Hutchinson’s spirometer from 1846.

(Wellcome Library, London/ Spirometer.)

An anthropological analysis of this study by Whitmarsh (2008, p. 7) evaluated how asthma in Barbados was “translated into a genetics of asthma and race, relying on the plurality of ‘asthma,’ ethnic identities, and other cultural categories.” Genetics research seemed particularly favorable in Barbados due to researchers’ moral agenda to better understand racial health disparities without the immediate criticism and protest of the American public. Researchers argue that Bajans are of African descent and will help in creating a complete genome map and will help explain how “black biology originates either in a prehistorical Africa or in the slave trade” (Whitmarsh, 2011, p. 166). This directly correlates to political etiology as a Johns Hopkins researcher proposes a selective advantage present in African Americans and Barbadians protecting them against a “worse asthma around high endotoxin levels” (Whitmarsh, 2011, p.166). Whitmarsh critiques that this researcher’s justification is a “speculative use of evolution” and infers that “African Americans and Barbadians, as populations of African descent, share a possible history of high exposure to parasites and diseases” (2011, p. 166). This suggests that the less severe phenotypic asthma in African Americans and Bajan populations is a result of selective advantage during the slave trade and is used to support historical racial classifications (Whitmarsh, 2011, p. 166). Furthermore, Whitmarsh proposes that using the evidence from this study allows researchers to “lend authority to the moral claims to be redressing the inequalities experienced by people ‘of African descent’ through genetics” and the urgency of the biomedical research (Whitmarsh, 2011, p. 166). He argues that the search for a genetic or biological basis for disease among an ethnic group “is an attempt to redress inequalities” and to “act on justice” (Whitmarsh, 2011, p. 167).

Whitmarsh’s (2011) analysis of the asthma study in Barbados also highlights the ready-to-recruit practices of the Johns Hopkin’s research team (Fisher, 2007). The researchers appealed to mothers of asthmatic patients by providing a form of personalized medicine and receiving blood samples, responses to an asthma questionnaire, dust samples, and spirometry readings. In coming to participants’ homes, mothers saw this as a “form of extended attention, information, and care they miss in the state or private health care system, and consider the genetics team a medical authority that rejoins the dismissive Barbadian medical authority” (Whitmarsh, 2011, p. 174). This relates to ready-to-consent and ready-to-recruit practices, as the participants may have felt as though they did not have “better alternatives” and may have joined without completely understanding the scope and purpose of the study in order to receive care options they would otherwise not have access to (Fisher, 2005). After participating, mothers felt as though they understood more about the diagnostic practices associated with asthma and appreciated the extra attention, though they did not believe that the information gathered by the researchers would benefit them or future generations (Whitmarsh, 2011, p. 174).

Researchers from the Johns Hopkins’ Barbados Asthma Genetics Study further benefited from the nationalized healthcare system that partners with the local government and U.S and U.K medical institutions to study the disease. The public health system in Barbados operates under a National Drug Formulary in which major American asthma medications are free to citizens of all ages and provides the “means for national pharmaceutical industry presence in Barbados” (Whitmarsh, 2008, p. 8). Furthermore, the emergency department of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital has an asthma bay, in which all patients presenting with asthmatic symptoms are guaranteed entry (Whitmarsh, 2008). Once admitted doctors rely on several measures to diagnose asthma in patients such as wheezing, family, history, and response to asthma medications. As Whitmarsh (2008) proposes, the use of response to medication as a diagnostic measure greatly profits the pharmaceutical company’s business. Pharmaceutical presence in Barbados puts pressure on medical professionals to diagnose using positive response to beta agonist asthma medication as well as increased prescription as the drugs are made readily available through the National Drug Formulary (pharmaceuticalization). However, he also argues that companies’ research efforts are somewhat contradictory as the pharmaceuticalization and expansion of the definition of asthma directly negate the efforts to pinpoint the exact cause of asthma. While researchers seek to better understand the root cause of asthma, more and more patients are being diagnosed with asthma and the criteria for asthma diagnosis continues to expand with the information produced by the current research (Whitmarsh, 2008).

An ethnographic study in 2009 on the prevalence of childhood asthma in the San Joaquin Valley in California further critiques the present approach to asthma research and calls for a deeper understanding of “public health issues on the local level” (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 362). The authors argue that while increased investigation on the interaction between genetics and the environment have shed new light on the causes of asthma; the effects of poverty, low literacy, and poor air quality have been neglected in the Valley (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 337). The California Health Interview Survey (CHIS 2007) revealed that Mexican children born in the United States have a much higher risk of developing asthma than do Mexican-born children and that the Valley “had the highest prevalence of diagnosed asthma for Mexican American children… nearly double the national average,” suggesting that the environment and poor air quality of the San Joaquin Valley significantly contribute to this increased risk (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 338). This evidence directly negates the hygiene hypothesis as “high rates of childhood asthma were found in rural counties that were simultaneously reported as having the highest rates of poor air quality in the country” (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 345). Furthermore, it provides evidence that children from urban communities are not the only ones at a high risk of developing asthma and that programs implemented in inner cities must also be developed for rural areas (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 345).

Although the prevalence of asthma in the Valley is shockingly high, the level of treatment and quality of care provided to the children is ineffective, as evidenced by the high frequency use of emergency care at hospitals (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 340). This may be attributed to the fact that “ethnic minorities are less likely to receive routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of health services,” especially in regions like the Valley in which high rates of poverty, lack of physician availability, and language barriers magnify the effects (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 340-1). Furthermore, as suggested by Wright and Subramanian (2007), the marginalized population of the Valley is “disproportionately exposed to environmental toxins” forming a community that is “socially toxic—a factor that may contribute to psychosocial stress related to increased asthma morbidity” (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009, p. 337). Not only does this allow for the criticism of current research on the macro level of genetics and highlight the need for a deeper understanding of the local environment, but it also introduces the concept of environmental racism. Environmental racism is understood as the “institutional practices that subject ethnic minority and poor communities to disproportionate levels of environmental hazards” (Martínez, 2005). The Valley’s air quality is among the worst in the nation and the pollutants and ozone of the region can exacerbate residents’ asthma, contributing to the high incidences of the disease among the children (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009). However, while federal clean air standards from the Environmental Protection Agency address the need for a change in the San Joaquin Valley, lack of communication with policymakers in the region has led to the postponing of regulation on gas emission by trucks (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009). This is a clear example of environmental racism as Republican lawmakers’ control over the regulations directly impacts the hazardous conditions that worsen children’s asthma conditions in the Valley (Schwartz & Pepper, 2009).

References

Bialostozky, A., & Barkin, S. L. (2012). Understanding sibilancias (wheezing) among Mexican American parents. Journal of Asthma, 49(4), 366-371.

Boger, G. (2009) ‘The Meaning of Neighborhood in the Modern City: Baltimore’s Residential Segregation Ordinances, 1910–1913’, Journal of Urban History 35(2): 236–58

Braun L. Race, ethnicity and lung function: A brief history. Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy: CJRT = Revue Canadienne de la Thérapie Respiratoire : RCTR. 2015;51(4):99-101.

Brookes, T. (1994). Catching my breath: an asthmatic explores his illness. Crown.

Eder, W., Ege, M. J., & von Mutius, E. (2006). The asthma epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(21), 2226-2235.

Fisher, J. A. (2007). “Ready-to-Recruit” or “Ready-to-Consent” Populations?: Informed Consent and the Limits of Subject Autonomy. Qualitative Inquiry : QI, 13(6), 875–894. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407304460

Jackson, M. (2009). Asthma: the biography. Oxford University Press.

Lemanske, R. F., & Busse, W. W. (2003). 6. Asthma. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 111(2), S502-S519.

Lock, S., Last, J., & Dunea, G.(2001). Galen. In The Oxford Companion to Medicine. : Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 Oct. 2017, from http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192629500.001.0001/acref-9780192629500-e-198.

Martínez, R.(2005). Environmental Racism. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States. : Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 Oct. 2017, from http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195156003.001.0001/acref-9780195156003-e-277.

Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R 2004 The global burden of asthma: Executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy 59: 469–478.

Metzl, J. M. (2010). Introduction: Why against health. Against health: How health became the new morality, 1-14.

Reardon, J. (2005) Race to the Finish: Identity and Governance in an Age of Genomics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rees, P.(2001). asthma. In The Oxford Companion to Medicine. : Oxford University Press. Retrieved 24 Sep. 2017, from http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192629500.001.0001/acref-9780192629500-e-41.

Schwartz, N. A., & Pepper, D. (2009). Childhood asthma, air quality, and social suffering among Mexican Americans in California’s San Joaquin Valley:“nobody talks to us here”. Medical anthropology, 28(4), 336-367.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2014). What is asthma? Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/asthma#

Warman, K. L., Silver, E. J., & Stein, R. E. (2001). Asthma symptoms, morbidity, and antiinflammatory use in inner-city children. Pediatrics, 108(2), 277-282.

Weitzman, M., Gortmaker, S., Walker, D. K., & Sobol, A. (1990). Maternal smoking and childhood asthma. Pediatrics, 85(4), 505-511.

Whitmarsh, I. (2008). Biomedical Ambiguity: Race. Asthma, and the Contested Meaning of Genetic Research in the Caribbean.

Whitmarsh, I. (2010). The art of medicine: asthma and the value of contradictions. The Lancet, 376(9743), 764.

Whitmarsh, I. (2011). American Genomics in Barbados: Race, Illness, and Pleasure in the Science of Personalized Medicine. Body & Society, 17(2-3), 159-181.

Wright, R. J., & Subramanian, S. V. (2007). Advancing a multilevel framework for epidemiologic research on asthma disparities. Chest journal, 132(5_suppl), 757S-769S.

« Back to Glossary Index