Introduction:

In the twenty first century there is one predominant form of medicine in Western developed countries, which is known as modern medicine (Hegde). This is comprised of treating illnesses and symptoms by prescribing drugs, conducting surgery and other scientific interventions such as radiation therapy (Hegde). However, there are numerous other systems of medicine globally known as ethnomedicine, including Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Unani, and Ayurveda (Birx). This encyclopedia entry will primarily focus on Ayurveda and its interactions with Western (or modern) medicine.

What is Ayurvedic Medicine:

Ayurvedic medicine is a system of medical practice developed in ancient India and is closely related to knowledge found in Hindu religious texts (Naranyaswamy). The exact timing of Ayurveda cannot be determined, but it can be traced back to around 3000 B.C. when it was practiced through oral tradition (Ven Murthy). The first written evidence of Ayurveda techniques comes from the Vedas, ancient Hindu scripture, in the twelfth century BC (Ven Murthy). Although Ayurveda is a medical system, it does not only focus on treating conditions but teaches healthy lifestyles including “personal and social hygiene” (Naranyaswamy). Another crucial aspect of Ayurveda is that each patient is different and therefore each treatment must be tailored for that specific person and their circumstances (Halliburton). Ayurvedic curative medicine consists of eight parts: “general medicine, pediatrics, mental disease, diseases of special sense organs, surgery, toxicology, gerontology and aphrodisiacs” (Narayanaswamy). The Encyclopedia Britannica mentions that Vedic texts primarily reference fever, consumption, diarrhea, and skin diseases as conditions for which treatment is needed and suggests numerous methods of treating these illnesses (Britannica). Ayurvedic treatment is composed of plant based medical interventions, special diets, and behavioral exercises such as yoga (Patwardhan, “Public perception of AYUSH”).

Credit: The Associated Press

This image shows the Ayurvedic practice of Shirodhara, pouring oil over the forehead (AP).

Currently, Ayurvedic medicine is primarily practiced in India in specific clinics as well as in some hospitals (Wolfrgam). However, some practices are spreading worldwide. In India, there are special colleges for Ayurvedic practitioners, though there are few in the United States (Wolfgram, NCCIH). Ayurvedic practitioners focus on three pillars: experience (anubhava), knowledge (sastra) and reason (yukti) (Wolfgram). Knowledge is primarily based off of oral traditions and information found in Ayurvedic texts (Wolfgram). Ayurvedic practitioners often track their medical experience by recording notes about each patient and the treatment path in order to better treat future patients (Wolfgram). Over time the medical experience of very successful practitioners may be added into the knowledge aspect through publishing their records (Wolfgram). Reason is principally utilized for diagnosis and uses the components of “logical inference”, analysis and interpretation (Wolfgram).

Examples of Ayurvedic Treatments:

Ayurveda is a vast field and contains numerous types of herbs for a multitude of conditions. Diet is a very important aspect of Ayurveda and a simple diet generally of plain rice and steamed vegetables is required before any treatment (Puri). Some herbs used for cleansing the body include garlic or neem (Puri). Along with this, hot oil massages are used for many different conditions to relax the body and promote rejuvenation of the body’s tissues (Puri). These treatments also have implications for improved mental health and immune health (Puri). Root bark is another Ayurvedic herb used to combat a number of conditions (Puri). It helps to stabilize heart rate, contributes to treating dysentery, has antibacterial properties and can be used to treat skin conditions (Puri). Another example of an Ayurvedic herb is Turmeric (Premila). Turmeric can be ingested in a milk potion to help with indigestion and as a cold remedy, or it can be externally used on the body as an antiseptic (Premila).

Credit: Washington Post

This is an image of the Ayurvedic herb, Turmeric. Turmeric is known for is numerous healing properties, such as treating skin diseases and possibly battling depression (Premila).

Historical Context:

Ayurvedic medicine thrived in India from its onset through the sixteenth century (Saini). During the sixteenth century, Indian Ayurvedic practitioners interacted with European medical practitioners and because there were many similarities between their techniques, a mutual respect developed (Saini). However, with the rise of rationalization philosophy in Europe, Europeans saw their methods as superior to the Ayurvedic traditions (Saini). In the eighteenth century colonial powers, namely the British established a presence in India and this led to a cultural exchange between traditional Indian ways and British methods (Saini).

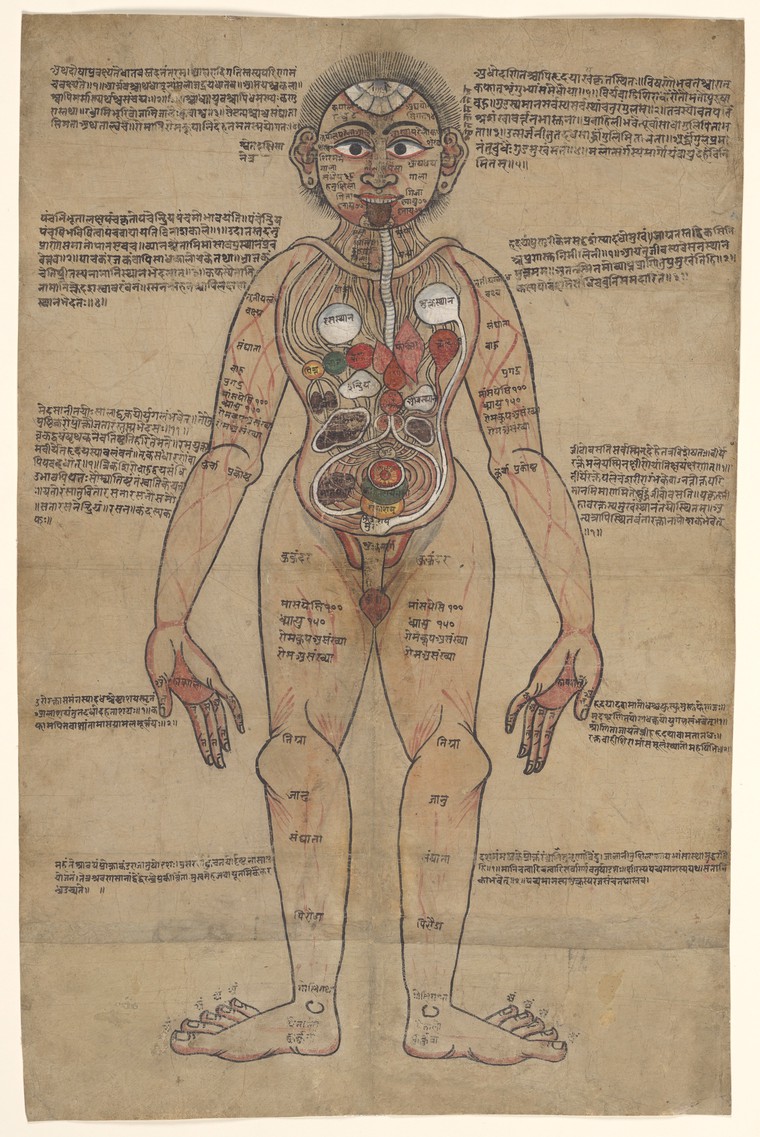

Credit: Wellcome Collection

This image shows the Ayurvedic understanding of human anatomy around 1800 A.D. The British had discovered different ideas of human anatomy through their dissection studies and rejected the Ayurvedic traditions (Saini).

The British were unfamiliar with the Ayurvedic system and the philosophy behind Ayurveda (Wolfgram). This led them to study Ayurveda plants and their effectiveness, and thus began the scientific testing and rationalization of Ayurvedic interventions (Wolfgram). They cultivated medicinal plants in order to study their properties and determine if these plants could be exported as cures back to Europe (Saini). This trend has continued on a wider scale by Western scientists as well as Indian scientists who hope to legitimize Ayurveda by proving its scientific basis (Wolfgram). This historical context contributes to the greater understanding of how active ingredients of medicinal plants are being used in Western medicine.

The British tried to implement a nationalized medical system in India which led to conflicts between traditional Indian medicine and the medical techniques introduced by the British (Bala). The British began to train some Indians in Western medicine and many of the upper class Indian families began to seek European treatments, especially surgery (Saini). In the nineteenth century, the British began to only support training in Western Medicine and established colleges such as Calcutta Medical College to promote western education (Saini). Many Indians were trained in Western Medicine and saw it as superior to the traditional Indian medical practices (Saini). There were, however, some practitioners who rejected Western medicine and continued to only practice Ayurveda (Saini). In fact, Ayurveda was one of the platforms used by Indian nationalists as part of anti-colonization movements (Bala). There was also a group who believed that integrating the two schools of thought would be the most effective mode of treatment and this idea still exists today (Saini). In most urban areas, Western medicine is heavily present, while Ayurvedic practitioners still prevail in rural areas (Saini;Wolfgram). The historical interactions between the British and Ayurvedic practitioners illustrate the current status of Ayurveda in modern India and the Western world. It also lends perspective to what types of medical treatment are currently available in India.

Perspectives:

The main controversy involving Ayurvedic medicine is its true efficacy, especially in comparison to Western Medicine. Wolfgram describes a lecture by Dr. Rajan, a professor at an Ayurveda College with degrees in both Western medicine and Ayurvedic medicine. Dr. Rajan discusses how Western medical practitioners have tested the scientific efficacy of Ayurvedic practices and adopted them (Wolfgram). One example is the application of oils on the body which was studied at Melbourne University and found to have health benefits in elderly people (Wolfgram). Dr. Rajan uses Western medicine to justify Ayurvedic practices (Wolfgram). However, some Ayurvedic practitioners believe the two schools of medicine should be kept separate from each other because they are not based on the same principals and therefore cannot be compared (Wolfgram). The problem with using modern science to authenticate Ayurvedic medicine is that it still gives modern science superiority and more legitimacy (Wolfgram).

Still, to opponents of Ayurvedic medicine, using Western science to justify Ayurvedic practices is the best method. There are biotechnologists who are researching “anticancer effects of phytochemicals,” integrating the knowledge of Ayurveda and Western Medicine (Wolfgram). These scientists identify the chemical structures of plants that are believed to have healing properties and determine the active ingredients present (Wolfgram). Furthermore, numerous Ayurvedic practices have gained traction in the Western world such as the concept of fasting (Rastogi). Although, fasting is a part of many world religions, Ayurveda promotes fasting because of its properties of revitalization and cleansing the body of toxins (Rastogi).

Credit: World Health Organization

This image depicts a Ayurvedic practitioner performed a massage on a patient after covering the patient’s body with a medicated oil (WHO).

A major criticism of Ayurveda is that it is a “pseudoscience” and many practices have not been scientifically proven (Patwardhan, “Public perception of AYUSH”). The nature of Ayurveda, experience based, leads to the obstacle that some treatments that work for one patient may not be successful in other individuals (Wolfgram). The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) describes that many Ayurvedic practices have not been studied in controlled, experimental environments and therefore it is unclear whether or not the remedies are truly beneficial. Furthermore, as described by the NCCIH, some Ayurvedic practices can be dangerous as they contain toxic metals. Herbs and plants used for medicines can be contaminated by pesticides, lead, arsenic and mercury (Patwardhan, “Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine”). This is further described in a piece by National Public Radio. However, the NCCIH does mention that some studies have been conducted to test the healing properties of turmeric and it has been found to have benefits for digestive conditions and arthritis.

Dr. B. M. Hegde discusses the ways in which Ayurvedic medicine is more effective than Western medicine. His argument entails that Western medicine is more focused on reductionist science and curing specific conditions which breeds more problems. Ayurvedic medicine takes a holistic approach and treats the whole body to maintain overall health. However, Dr. Hege concludes by acknowledging both forms have benefits and must be used together in order to provide the most effective treatments.

An anthropological perspective compares the ideas of ethnomedicine and biomedicine (Birx). Ayurveda is an example of ethnomedicine and Western medicine is considered biomedicine. Ethnomedicine was studied by anthropologists in the early to mid twentieth century and compared to Western medicine, ethnomedicines were thought of as “primitive” and “irrational” (Birx). Anthropologists generalized ethnomedical practices in order to bolster the stark differences between them and biomedicine (Birx). They primarily focused how ethnomedicines were heavily based on culture whereas, ideally, Western medicine was “scientific” (Birx). However, as research progressed this method of thinking was not feasible (Birx). In different cultures and geographic locations, different conditions were seen as problematic symptoms (Birx). This included Western medicine, thus biomedicine was also rooted in culture (Birx). Furthermore, the old use of the term ethnomedicine included practices such as Ayurveda, which possessed many characteristics of biomedicine such as “educational institutions… pharmacopoeia…and written texts” (Birx). Thus, in the late twentieth century, many anthropologists began to see biomedicine as a form of ethnomedicine and that all professional medical systems contribute to the global health (Birx).

These perspectives are vital to understand how medical systems are evaluated currently and whether or not these evaluations are fair. Although Western medicine is more scientifically proven and focuses on direct cures, Ayurveda is more personalized and promotes overall health. Thus, studying the different perspectives in relation to ethnomedicine and biomedicine highlights the importance of integrating the beneficial philosophies from both fields of medicine (Wolfgram).

Politics of Health:

Ayurvedic medicine can be analyzed through Williams’ idea of pharmaceuticalization. Originally, Ayurvedic practitioners used their knowledge and experience to create specific prescriptions for each of their patients and give patients a sort of recipe (Halliburton). Often the patients themselves could prepare the recipes (Halliburton). The practitioners did not believe themselves to be owners of any type of ayurvedic herb or medicine (Halliburton). However, this practice is losing its prevalence as many “ayurvedic medicines began to be mass-produced in standardized forms by ayurvedic pharmaceutical companies” (Halliburton). New patent acts in India allow multinational pharmaceutical companies to patent ayurvedic drugs (Halliburton). For example, reserpine, an antipsychotic medication, was patented in the United States but imitated the “active ingredient in an ayurvedic drug for mental disorders” (Halliburton). This drug still creates a large sum of profit, but no South Asian medical practitioners share any of it (Halliburton). India was able to defeat another U.S. patent where university students attempted to patent turmeric based off of its healing properties (Halliburton). In 2005, India passed laws that disallowed other countries from patenting Ayurvedic knowledge but continues to allow Indian companies to patent Ayurveda (Halliburton). The idea of converting herbal medicines into marketable pharmaceuticals, highlights Williams’ idea of drug innovation being a significant part of the biomedical industry (Sismondo 27). The practice of patenting Ayurvedic medicines by the United States represents increasing the consumer market of the product (Sismondo 29). Furthermore, the Indian government allowing Indian companies to patent Ayurvedic ingredients depicts the close relationship between regulatory practices of the state and the pharmaceutical industry as mentioned by Williams (Sismondo 22).

The history of Ayurveda practitioners and the British colonizers can be connected to Foucault’s theory of biopower. There has been debate over whether and how the British used medical intervention to establish power over India as a colony (Saini). Foucault describes “biopower” as the “diverse techniques for achieving subjugation of bodies and the control of populations” (Foucault). The British utilized their power by shutting down Ayurvedic institutions and promoting Western medicine, which allowed them to control the population (Saini). Through this, they also gained control over the bodies of the Indian population, as they were able to control what types of treatments and medicines the population received.

Works Cited

“Ayurveda Over Western Medicines.” Performance by B M Hegde, TEDxTALK, Youtube, 7 Dec. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzTvEK1sVi0.

“The Ayurvedic Man, C.18th Century.” Wellcome Collection, Wellcome Collection.

“Ayurvedic Medicine: In Depth.” National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 7 Apr. 2016, nccih.nih.gov/health/ayurveda/introduction.htm.

Bala, Poonam. Contesting Colonial Authority: Medicine and Indigenous Responses in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century India. Primus Books, 2016.

Birx, H. James. Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Vol. 2, SAGE Publ., 2006.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Ayurveda.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 28 Mar. 2018, www.britannica.com/science/Ayurveda.

Chen, Angus. “Toxic Lead Contaminates Some Traditional Ayurvedic Medicines.” NPR, NPR, 31 July 2015, www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/07/31/428016419/toxic-lead-contaminates-some-traditional-ayurvedic-medicines.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. Vol. 1, Vintage Books, 1990.

Halliburton, Murphy. “Resistance or Inaction? Protecting Ayurvedic Medical Knowledge and Problems of Agency.” Journal of the American Ethnological Society, vol. 38, no. 1, Feb. 2011, pp. 86–101., anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01294.x.

Khurup, P. “World Health Organization.” World Health Organization, WHO, 1977.

Narayanaswamy, V. “ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF AYURVEDA.” Ancient Science of Life, vol. 1, no. 1, July 1981, pp. 1–7. NCBI, US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health.

Patwardhan, Bhushan. “Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Comparative Overview.” Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2, no. 4, 27 Oct. 2005, pp. 465–473. NCBI, US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health, doi:10.1093/ecam/neh140.

Patwardhan, Bhushan. “Public Perception of AYUSH.” Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, vol. 6, no. 3, July 2015, pp. 147–149. NCBI, US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health, doi:10.4103/0975-9476.166389.

“Pharmaceutical Lives.” The Pharmaceutical Studies Reader, by Sergio Sismondo and Jeremy A. Greene, Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

Premila, M. S. Ayurvedic Herbs: a Clinical Guide to the Healing Plants of Traditional Indian Medicine. Haworth Press, 2006.

Puri, Harbans Singh. Rasayana: Ayurvedic Herbs for Longevity and Rejuvenation. Taylor & Francis, 2003.

Rastogi, Sanjeev. Ayurvedic Science of Food and Nutrition. Springer-Verlag New York, 2016.

Saini, Anu. “Physicians of Colonial India (1757–1900).” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, vol. 5, no. 3, July 2016, pp. 528–532. NCBI, US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health, doi:10.4103/2249-4863.197257.

Solanki, Ajit. “India Ayurveda Medicine.” Associated Press, Associated Press, Ahmedabad, 24 Dec. 2016.

“Traditional Chinese Medicine: In Depth.” National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 23 Mar. 2017, nccih.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/chinesemed.htm.

Trivedi-Grenier, Leena. “On A Hot Day, Indians Love To Sip A Spicy Soda That’s A Bit Funky, Too.” NPR, NPR, 14 Apr. 2017, www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/04/14/523405061/on-a-hot-day-indians-love-to-sip-a-spicy-soda-thats-a-bit-funky-too.

“Unani Medicine.” Unani Medicine – an Overview, Science Direct, www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/unani-medicine.

Ven Murthy, M R. “Scientific Basis for the Use of Indian Ayurvedic Medicinal Plants in the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders.” Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 10, no. 3, 2010, pp. 238–246., doi:10.2174/1871524911006030238. Bentham Science.

“Washington Post.” Washington Post, 20 Aug. 2017.

Wolfgram, Matthew. “Truth Claims and Disputes in Ayurveda Medical Science.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, vol. 20, no. 1, 24 May 2010, pp. 149–165. Anthrosource.

« Back to Glossary Index