Definition

Biorepositories (more commonly known as biobanks) are institutions that collect samples of genetic material from individuals, which are then made available to scientists for use in research about disease and health. They are largely used to connect genetic characteristics to particular diseases and their effects (Lipworth, Forsyth, & Kerridge, 2011). Biobanks can be affiliated with a variety of institutions, public or private, that include hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, governments, and universities, to name a few (Tutton, 2010). With donors originating from hospitals, the material they consent to donating is often leftover from lab work or operations they have done, most often routine bloodwork, but biobanks can collect all types of tissues, and even whole and partial organs (De Souza & Greenspan, 2013). Patients sign a consent form that is often included with other routine medical paperwork provided upon arrival to the clinic. If the patient signs the consent form, their leftover biological material is linked with their medical record but de-identified to maintain patient anonymity per HIPAA regulations. The genetic material and corresponding health information is transferred to the biobank and stored, where it can be accessed by researchers who intend to use it for their studies. An example of this process from Vanderbilt University’s Medical Center (VUMC) biobank (BioVU) is shown in more detail in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The process of cataloging genetic samples at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Source: https://victr.vanderbilt.edu/pub/biovu/index.html?sid=217

Biobanks are not very uniformly regulated, so organizations have different regulations for the de-identification process. Some institutions keep contact information for patients that is connected to their sample in case researchers need to contact patients for any reason, but there are also institutions that completely retract all information, thus making the samples completely anonymous and essentially removing all of the patient’s control over their samples (Harrell & Rothstein, 2016). The bottom of Figure 1 notes that, for this example organization, patients can revoke their consent at any time.

In most biobanks that are linked with hospitals, patients do not receive any kind of financial compensation for their donation; the action is purely voluntary. However, this brings about issues of ownership surrounding the material, which I will discuss in depth later. Sources of funding for biobanks vary widely depending of the type of institution and its affiliation. Although many biobanks are owned by independent institutions, there is still a good deal of public funding that goes into the operation of a biobank (Tupasela & Stephens, 2013). Most biobanks are also not independent organizations; a vast majority of them are affiliated with another organization or another group of biobanks that collaborate on research efforts (Harrell & Rothstein, 2016).

Historical Context

Biobanks have developed over time as an answer to the shortage of genetic material needed for widespread and generalizable studies on genes and their potential health implications. Some of the first biobanks were developed for the needs of specific projects (De Souza & Greenspan, 2013). Most of these were smaller institutions affiliated with universities that sought to provide a collection of samples available for research. Biobanks are only recently taking off as commercial institutions, and new technologies have allowed them to expand their capabilities and goals; some are completely operated by robots, others focus on specific projects, some work for profit, and there are even virtual biobanks beginning to grow in popularity (De Souza & Greenspan, 2013).

Because the industry is still relatively new and only beginning to come together as a uniform set of organizations, the regulations surrounding biobanks and their functioning are sparse and often inconsistent across institutions and countries. Despite this, biobanking has been largely influenced by HIPAA and its regulations throughout history. Specifically in the United States, HIPAA has had a large impact on specific regulations for biobanks, with most of the new technological developments being required to comply with HIPAA (Harrell & Rothstein, 2016). The de-identification step of the biobanking process and its compliance with HIPAA privacy regulations is the largest compliance issue. Because genetic material can never be entirely anonymous, researchers obtaining data from some biobanks must also agree to not try to reidentify donors, even if they had the means to do so (Harrell & Rothstein, 2016).

The issue of biobanks also has historical roots in some other controversial stories, including the case of Henrietta Lacks. Before biobanks were popular practice, Henrietta Lacks’ story was sparking controversy about ownership rights and informed consent issues surrounding tissue donation. While being treated for cervical cancer in the early 50s, doctors took tissue samples from her without her knowledge or consent. These tissue samples later became vital to the discovery of a variety of different medical developments, including the discovery of the polio vaccine. The cells in the tissue samples (known as the HeLa cell strain) are involved in thousands of different patents today and are still used in medical research. The Lacks family was not informed about the cells until the 1970’s and Lacks’ story has become a centerpiece of the discussion about property rights regarding genetic material. Because this case took place largely before the development of biobanks, it has not changed their policies necessarily, but it has certainly had an influence during their creation, and the case has also influenced the public’s opinions surrounding genetic testing and collection (Nisbet & Fahy, 2013). Receiving informed consent is now the first step of all biobanking research, and the ownership of genetic material is a topic still being discussed today.

The issue of commercialization of human tissues was also addressed in the 1990 court decision, Moore v. Regents of the University of California. In a similar but much more recent case to Henrietta Lacks, John Moore’s cells were taken by UCLA researchers and developed into a cell line that eventually was commercialized for research. In this case, the California Supreme Court ruled that Moore’s discarded tissue samples and blood were in fact not his own property, and that patients do not have a right to any of the profits that come from using their cells or genetic material in research (Tutton, 2010). This case has set the tone for commercialization of genetic material and has had large implications for the importance of informed consent in the biobanking process, which I will discuss later.

Controversy/Perspectives

The economics of biobanks are particularly controversial. Being such a new and fast-growing industry, there are many uncertainties with how the future for biobanking should be approached and how the standards should be developed. Standards and policies for regulating and overseeing biobanks economically are just as important as the standards surrounding ethics and property rights that history has provided lessons about. With minimal regulation, the biobanks could potentially become competitive in nature, with different countries and organizations struggling to maintain their own regional power, which could simply lead to a waste of public funding (Tupasela & Stephens, 2013). With no concrete returns being produced by their affiliated biobanks, institutions like hospitals might not want to keep funding them for longer periods of time, and they could thus become dependent entirely on public funding. (Tupasela & Stephens, 2013). Many have also raised the question of the potential economic failure of a biobank. Funding is limited for all projects of this nature, and so it is likely that there will be a failure or merger of biobanks in the future, which raises its own set of ethical and political dilemmas (Tupasela & Stephens, 2013).

Furthermore, one of the most central controversies in the world of biobanks is that of property rights. Who technically owns the biological material of the patients once it has been donated? Currently, the answer to this is variable. Different countries and governments are creating their own rules, and without many overarching regulations, each entity is making their own rules (Tutton, 2010). In the United States, as mentioned above in the historical context, one particular court case has ruled that patients do not have rights to their discarded tissue, nor do they have the right to any compensation from the profits their genetic material could potentially generate. While this ruling echoes the themes of the historical Henrietta Lacks case, it was produced only in the early years of biobanking, and thus it is unclear how these rulings will affect the future development and growth of this industry.

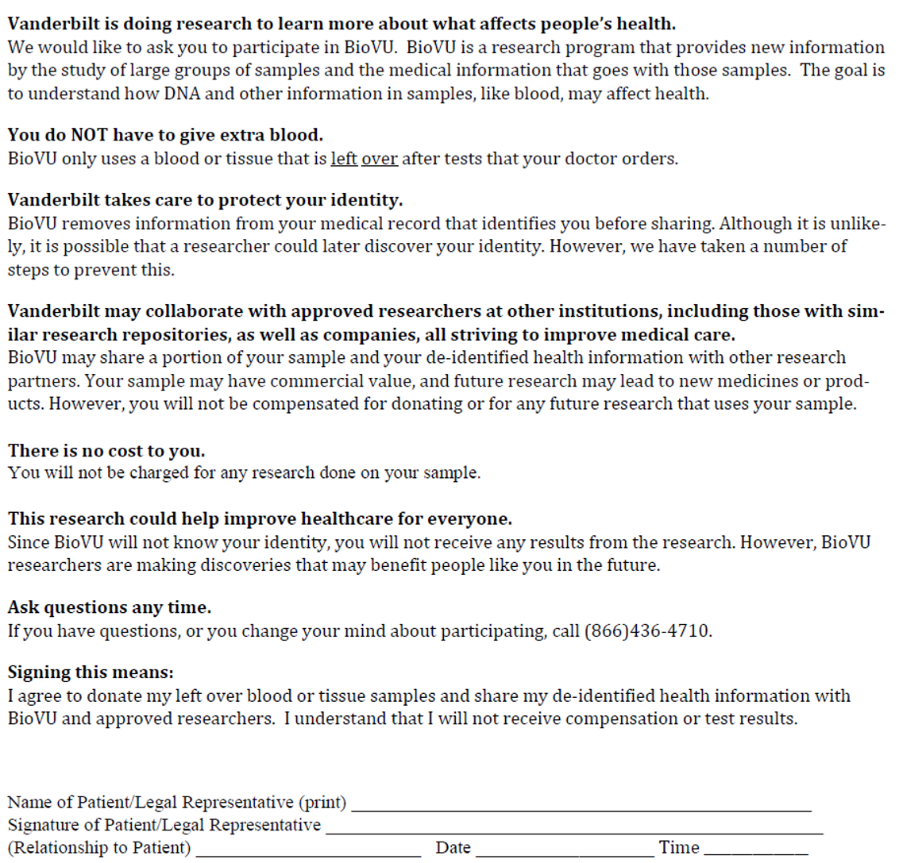

Consent is a large issue in the world of biobanks, and this industry uniquely mixes the issues of patient autonomy and property rights. Because most material donated to most biobanks is voluntarily donated and the donors receive no financial compensation, this leads to debate over how much organizations should be using these donated samples for profit and financial benefit from research. Previous court rulings have decided that tissue itself is not property, and therefore cannot be owned by anyone, even the person from which the tissue came (Tutton, 2010). If this is the case, then the samples collected in biobanks do not technically belong to anyone, and we must consider this when making decisions about consenting to donate to biobanks. If this ruling is to stand for a longer period of time, donors should be clearly informed that they have no rights to their tissues once they are donated as a part of the informed consent process. An example of the consent form for BioVU given to patients at VUMC is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. An example of a consent form given to patients for a biobanking program at VUMC.

Relation to Politics of Health

Biobanks are linked directly to the politics of health because the process for donating samples is an example of informed consent and relates to the concept of informed refusal. Benjamin describes informed refusal as extending informed consent through, “a broader social field concerned not only with what is right, but also with the political and social rights of those who engage technoscience as…tissue donors” (Benjamin, 2016). Many of the controversies surrounding informed consent during the process of donating genetic material (as was first evidenced in the case of Henrietta Lacks), are directly related to these social rights of donors: their right to own (or not own) their genetic material, the right to any compensation that may result from their donation, and their right to have the ability to choose what happens with their genetic material.

Biobanks can also be examples of the state’s assumed biopower over specific populations. Specifically, it is an example of regulatory power. The state maintains its control over individuals’ bodies by making them feel in control and regulating the relationship between an individual’s body and their health. Many of the controversies surrounding biobanks involve the ownership of the material and the donor’s rights to compensation. As has been reinforced by the court system in the United States, once an individual donates their genetic material, they transfer their power over their own biological material (and thus themselves) to the state or another institution. This confiscation of power and ownership is one way through which the multitude of institutions in charge of biobanks maintain their power over individuals’ bodies.

As Foucault discusses, the goal of these institutions is often to achieve, “the vitality of bodies and populations, visible in the emergence of diverse domains of governance and knowledge” (McGee & Warms, 2013). This is consistent with biobanks, because they are intended to ease the process of genetic research and ultimately improve population health. But as the industry develops and consistent regulations for biobanks become more prevalent, large institutions will have the potential to exert much more power over individuals’ bodies.

References

Benjamin, R. (2016). Informed refusal: Toward a justice-based bioethics. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 41(6), 967-990.

De Souza, Y. G., & Greenspan, J. S. (2013). Biobanking past, present and future: responsibilities and benefits. AIDS (London, England), 27(3), 303.

Harrell, H. L., & Rothstein, M. A. (2016). Biobanking research and privacy laws in the United States. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 44(1), 106-127.

Lipworth, W., Forsyth, R., & Kerridge, I. (2011). Tissue donation to biobanks: a review of sociological studies. Sociology of health & illness, 33(5), 792-811.

McGee, R., & Warms, R. (2013). Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. In. Thousand Oaks. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. Retrieved from http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/theory-in-social-and-cultural-anthropology. doi:10.4135/9781452276311

Nisbet, M. C., & Fahy, D. (2013). Bioethics in popular science: evaluating the media impact of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks on the biobank debate. BMC medical ethics, 14(1), 10.

Tupasela, A., & Stephens, N. (2013). The boom and bust cycle of biobanking–thinking through the life cycle of biobanks. Croatian medical journal, 54(5), 501.

Tutton, R. (2010). Biobanking: social, political and ethical aspects. eLS.

« Back to Glossary Index