Definition

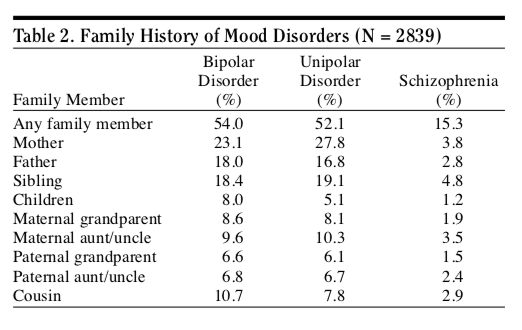

Bipolar disorder is a manic-depressive disorder that “cause[s] changes in a person’s mood, energy, and ability to function” (Parekh). It is characterized by deregulated moods, which can lead to impulsivity, participation in risky behaviors, alcohol and substance abuse, and interpersonal problems (Hirschfeld et al., Screening 53). The lifetime prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorders has been found to be between 2.6% and 6.5% (Hirschfeld et al., Mood Disorder Questionnaire 1873). Bipolar disorder, however, frequently goes unrecognized or undiagnosed because symptoms can vary greatly between individuals (Hirschfeld et al., Mood Disorder Questionnaire 1873). Manifestations of the disorder can range from mild depression and hypomania to severe forms of mania and depression, sometimes accompanied by psychosis (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 241). According to a national survey conducted in the United States, approximately half of patients have to wait at least five years for a correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and this occurs only after patients have visited an average of four different doctors (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 242). This delayed diagnosis and consequently delayed treatment can be dangerous for the patient, as bipolar disorder is associated with great morbidity: the mortality rate for individuals with bipolar disorder is two to three times higher than that of the general population, and the risk of suicide is also higher (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 241). Bipolar disorder also appears to be somewhat hereditary. One 2002 demographic study of patients with bipolar disorder found that over 50% of the 2839 surveyed individuals reported having at least one family member with bipolar disorder (Kupfer et al. 122). The table below displays the results of this study.

Figure 1. Family History of Mood Disorders. Source: Kupfer et al. 2002. This table shows the familial patterns of bipolar disorder. Over 50% of surveyed individuals with bipolar disorder indicated that they had a family member who also had bipolar disorder. The table gives additional information regarding the relation of said family member to the surveyed individual.

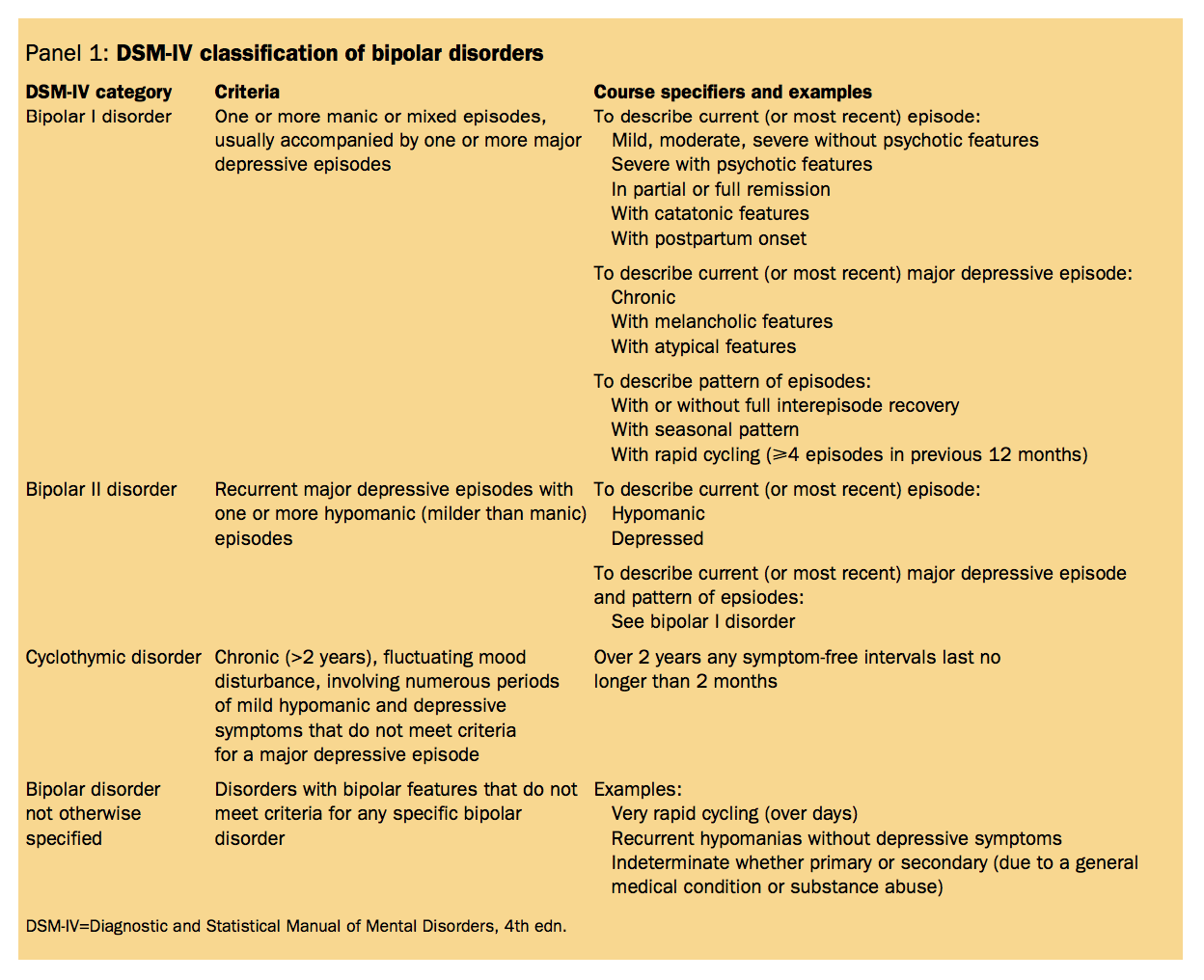

While most research has focused solely on bipolar I disorder, there are a few different categorizations of bipolar disorder that fall under the broader term of “bipolar spectrum disorders.” These include bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. Bipolar I disorder is characterized by “either one or more manic or mixed episodes, or both manic and mixed episodes and at least one major depressive episode, while bipolar II disorder is characterized by “one or more episodes of major depression and at least one hypomanic episode” (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 241). The table below summarizes the DSM-IV classifications of the different bipolar spectrum disorders.

Figure 2. DSM-IV Classification of Bipolar Disorders. Source: Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 2002. This table explains the official classifications of each type of bipolar spectrum disorder according to the DSM-IV. The table includes diagnostic criteria for bipolar I, bipolar II, cyclothymic disorder, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified.

According the American Psychiatric Association, a manic episode is a week-long period where an individual is very excited or irritable in an extreme way, has more energy than usual, and experiences at least three of the following:

- “Exaggerated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Less need for sleep

- Talking more than usual; talking loudly or quickly

- Easily distracted

- Doing many activities at once; Scheduling more events in a day than can be accomplished

- Increased risky behavior (e.g. reckless driving, spending sprees)

- Uncontrollable racing thoughts or quickly changing ideas or topics” (Parekh).

Symptoms of a manic episode demonstrate a clear deviation from normal behavior, and may be so severe that they necessitate hospitalization (Parekh). A hypomanic episode is similar to a manic episode, but the symptoms are not as severe and generally do not impair an individual’s ability to function to the point of requiring hospitalization (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 241). The American Psychiatric Association describes major depressive episodes as two week periods in which a person exhibits at least five of the following:

- “Intense sadness or despair; feeling helpless, hopeless, or worthless

- Loss of interest in activities once enjoyed

- Feeling worthless or guilty

- Sleep problems – Sleeping too little or too much

- Feeling restless or agitated (e.g. pacing or hand-wringing), or slowed speech or movements

- Changes in appetites (increase or decrease)

- Loss of energy, fatigue

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering making decisions

- Frequent thoughts of death or suicide” (Parekh).

The TED-Ed video below summarizes the symptoms manic and depressive episodes, and the classifications of bipolar I and bipolar II disorders.

Figure 3. Helen M. Farrell’s TED-Ed talk “What is Bipolar Disorder?”

Historical Context

Human moods can be thought of as existing on a spectrum. The outermost ends of the spectrum represent the extremes of human emotion, both of which are experienced in bipolar disorder: melancholia, the lowest low, and mania, the highest high (Mason et al. 1). These two extremes of mood were first documented in human history by ancient Greeks, and were first systematically described by Hippocrates, an ancient Greek physician (Mason et al. 1).

Figure 4. Hippocrates. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Hippocrates described melancholia as a “pathological state of severe sadness,” and described mania as the result of “an excess of yellow bile” (Mason et al. 2). Hippocrates and his contemporaries believed that melancholia and mania were not innate personality traits, but were instead biologically driven (Mason et al. 2). From antiquity to the nineteenth century, these extreme moods were thought of as two separate disorders; it was not until 1851 when French scholar Jean-Pierre Falret created a new concept of a psychiatric disorder which encompassed both extremes (Mason et al. 2). He called this disease “folie circulaire,” and defined it as manic and melancholic episodes separated by periods of no symptoms (Angst and Sellaro 445). In 1854, Jules Baillarger developed the term “folie à double forme” to describe cyclic episodes of mania and melancholia without symptom-free periods (Angst and Sellaro 445). These two variations of the disorder gained popularity and the concept of a “cycling mood disease” became widely accepted before the end of the nineteenth century (Mason et al. 2). Emil Kraepelin, a German psychiatrist, later attempted to combine these various descriptions into one definition, creating concepts for disorders he called “dementia praecox” and “manic depressive insanity,” which are now known as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, respectively (Mason et al. 3). Kraepelin’s descriptions “described the full spectrum of mood dysfunction” that involved manic and depressive episodes (Mason et al. 3). The first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) was published in 1952 and was the first attempt to categorize and standardize mental illness (Mason et al. 3). The DSM-I classified manic-depression as a psychotic disorder (Mason et al. 3). Bipolar disorder was first included in the third edition, DSM-III, and its definition has continued to be updated in subsequent editions.

Controversy

Bipolar disorder is very manageable with appropriate treatment. The main aim of treatment for the disorder is to prevent recurrence and to prevent suicidal acts (Müller-Oerlinghausen 243). The most common treatments for bipolar disorder are medications, psychotherapy, or a combination of the two. Due to the high risk of recurrence and suicide in individuals with bipolar disorder, a “long-term prophylactic pharmacological treatment” is often suggested (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 241). A 2002 demographic study of individuals with bipolar disorder found that three quarters of the surveyed patients were taking between one and three medications: over one third of the patients were taking lithium or an anticonvulsant alone, over 50% of the patients were taking an antidepressant, and 25% of the patients were taking a benzodiazepine (Kupfer et al. 123). Lithium salts are often the first-choice long-term preventive treatment for bipolar disorder, although treatments are being revised as new drugs become available (Müller Oerlinghausen et al. 243). An up-and-coming style of treatment is anticonvulsant drugs. Carbamazepine is one such drug that is being prescribed more frequently now; it is effective in the treatment of patients with bipolar spectrum disorders, but is less effective in the treatment of patients with classical bipolar disorder (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 244). Additionally, off-label use of valproic acid and atypical antipsychotics has increased in several countries (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 244).

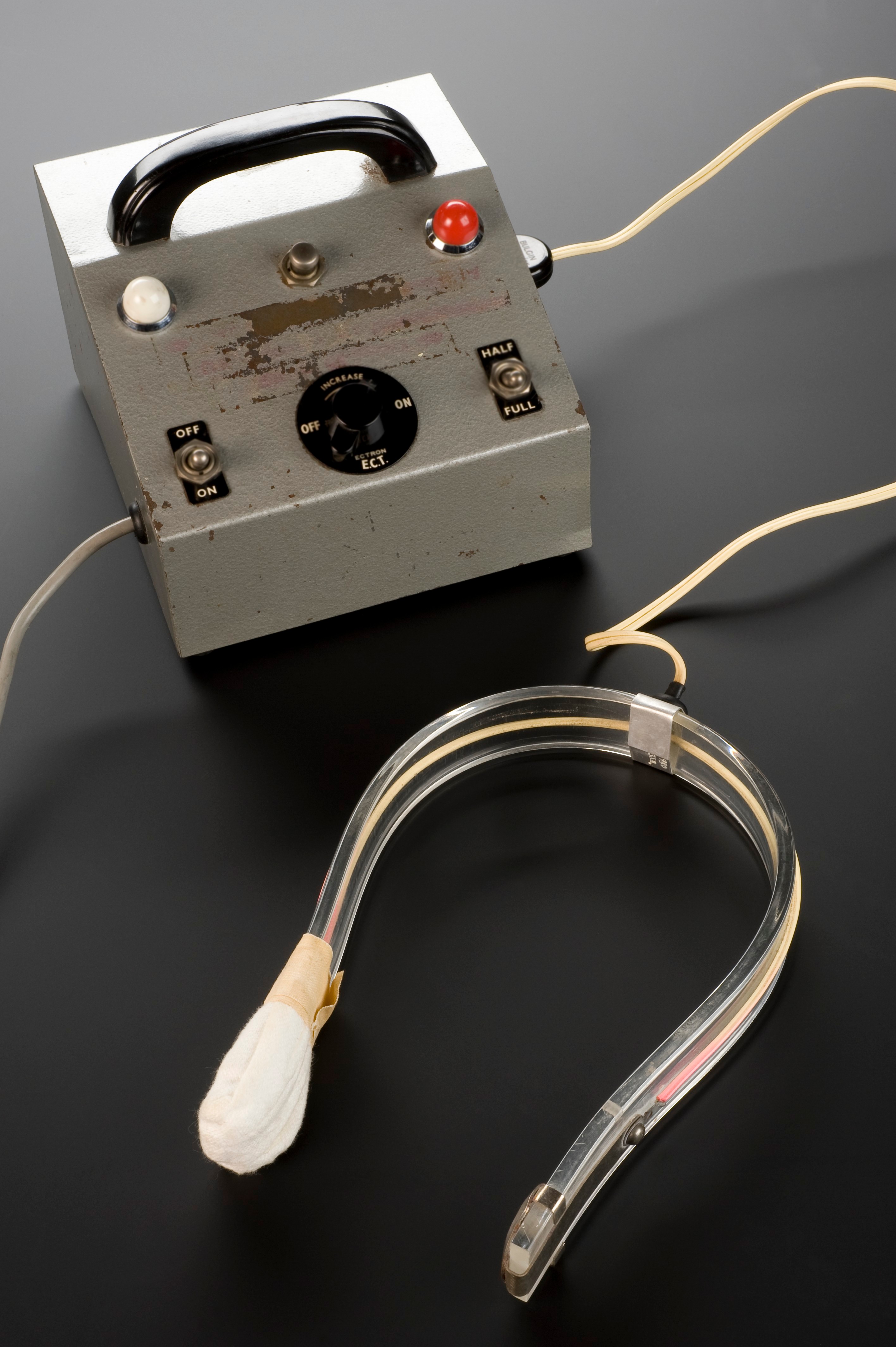

When an individual with bipolar disorder does not respond to medication or psychotherapy, however, a different, more controversial treatment may be utilized: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). ECT was developed by Ladislas Joseph von Meduna in 1934 (Valentí et al. 53). ECT is a treatment that involves brief electrical stimulation of the brain while the patient is under anesthesia; it is administered by a team of trained medical professionals including a psychiatrist, an anesthesiologist, and a nurse or physician’s assistant (McDonald and Fochtmann). The American Psychiatric Association describes the process of ECT:

“At the time of treatment, a patient is given general anesthesia and a muscle relaxant and electrodes are attached to the scalp at precise locations. The patient’s brain is stimulated with a brief controlled series of electrical pulses. This causes a seizure within the brain that lasts for approximately a minute. The patient is asleep for the procedure and awakens after 5-10 minutes” (McDonald and Fochtmann).

Figure 5. An electroconvulsive therapy machine. Source: Wellcome Collection.

The effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy is debated. Its use raises ethical questions both for mental health professionals who may recommend it and for patients to whom it has been prescribed. On one hand, if it is indeed a safe and effective treatment, it could be unethical to withhold it from patients who could potentially benefit; however, if it is an unsafe treatment that could lead to permanent brain damage, it would be unethical to use, regardless of potential benefits (Reisner 199). Many mainstream psychiatrists agree that ECT is safe and effective, but there exists a vocal minority that claims that ECT should not be used since it causes permanent brain damage (Reisner 199). This group claims that “the therapeutic effects of ECT are derived from a lobotomy-like effect, or from euphoria or apathy sometimes seen with a closed head injury” (Reisner 199).

ECT treatment has, in fact, been associated with short-term memory loss and difficulty learning, although empirical evidence has shown that, in most cases, the issues resolve within a couple of months (McDonald and Fochtmann). At times, patients complain of memory problems up to three years after receiving ECT treatments, although it is difficult to confirm that these issues are not due to other external factors (Reisner 203). Critics of ECT tend to cite these individual cases where the aftermath of ECT has allegedly led to “devastating life consequences” (Reisner 203). Supporters of ECT often do not rule out the possibility of long-lasting effects, but emphasize that controlled studies have found no conclusive evidence that ECT causes such long-term consequences (Reisner 204). There are findings of correlations between ECT and brain abnormalities, but this correlation does not necessarily indicate a causal relationship (Reisner 214).

Relation to Politics of Health

Bipolar disorder relates to the politics of health through the concepts of medicalization and pharmaceuticalization. Conrad describes the concept of medicalization as “defining a problem in medical terms, usually as an illness or disorder, or using a medical intervention treat it” (Conrad 3). This is applicable to bipolar disorder because defining the disorder in clinical terms represents the classification of extreme moods as a medical problem that requires a medical solution. Additionally, medical interventions are used to treat bipolar disorder. These medical interventions demonstrate the pharmaceuticalization of bipolar disorder. Williams et al. define pharmaceuticalization as “the translation or transformation of human conditions, capabilities and capacities into opportunities for pharmaceutical intervention” (Williams et al. 20). In the case of bipolar disorder, pharmaceuticals have been developed for the purpose of regulating moods, which arguably fall into the category of human conditions. As discussed earlier, medications such as lithium salts, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines have become the primary instruments for treatment and long-term management of bipolar disorder. This represents a significant shift from the previous theories that cited environmental and developmental factors as the sole causes for bipolar disorders; as a result, psychotherapy was the primary treatment for bipolar disorder at the time (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 246). Use of psychotherapy has since been significantly reduced with the introduction of effective pharmaceuticals (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 246). Sometimes, specific psychotherapies are still used, but typically in combination with pharmaceuticals, not as the sole or primary treatment. Other times, psychotherapy is used to improve a patient’s likelihood of complying with their regimen of medications (Müller-Oerlinghausen et al. 246). Clearly, in the process of pharmaceuticalization, the emphasis has shifted away from psychotherapy and onto medications and drugs as the primary tools for treating and managing bipolar spectrum disorders.

Works Cited

Angst, Jules, and Robert Sellaro. “Historical Perspectives and Natural History of Bipolar Disorder.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 48, 15 Sept. 2000, pp. 445-57, DOI:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00909-4.

Conrad, Peter. “Shifting Engines of Medicalization.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, PDF ed., vol. 46, Mar. 2005, pp. 3-14.

Hirschfeld, Robert M.A., et al. “Development and Validation of a Screening Instrument for Bipolar Spectrum Disorder: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire.” The American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 157, no. 11, Nov. 2000, pp. 1873-75, DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873.

Hirschfield, Robert M. A., et al. “Screening for Bipolar Disorder in the Community.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, vol. 64, no. 1, Jan. 2003, pp. 53-59. Europe PMC, europepmc.org/abstract/med/12590624.

Kupfer, David J., et al. “Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Individuals in a Bipolar Disorder Case Registry.” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, PDF ed., vol. 63, no. 3, Feb. 2002, pp. 120-25.

Mason, Brittany L., et al. “Historical Underpinnings of Bipolar Disorder Diagnostic Criteria.” Behavioral Science, vol. 6, no. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 1-19. PMC, DOI:10.3390/bs6030014.

McDonald, William, and Laura Fochtmann. “What is Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)?” American Psychiatric Association, Jan. 2016, www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ect.

Müller-Oerlinhausen, Bruno, et al. “Bipolar disorder.” The Lancet, vol. 359, no. 9302, 19 Jan. 2002, pp. 241-47. Science Direct, DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07450-0.

Parekh, Ranna. “What Are Bipolar Disorders?” American Psychiatric Association, Jan. 2017, www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/bipolar-disorders/what-are-bipolar-disorders.

Pontius, Paul. Engraving: Bust of Hippocrates. 1638. Wellcome Collection, wellcomecollection.org/works/kgkv65up.

Reisner, Andrew D. “The Electroconvulsive Therapy Controversy: Evidence and Ethics.” Neuropsychology Review, vol. 13, no. 4, Dec. 2003, pp. 199-219. Springer Link, DOI:10.1023/B:NERV.0000009484.76564.58.

Science Museum, London. Electroconvulsive Therapy Machine, Baldock, Hertfordshire, 1. Wellcome Collection, wellcomecollection.org/works/m5qs4dwz.

Valentí, Marc, et al. “Electroconvulsive Therapy in the Treatment of Mixed States in Bipolar Disorder.” European Psychiatry, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 53-56, DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.10.011.

Williams, Simon J., et al. “The Pharmaceuticalization of Society? A Framework for Analysis.” The Pharmaceutical Studies Reader, edited by Sergio Sismondo and Jeremy A. Greene, PDF ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015, pp. 19-32.

« Back to Glossary Index