Note: Originally published on Feb. 28, 2017 by Cayenne Buell; Rewritten on April 1, 2017 by original author

Definition of the Term

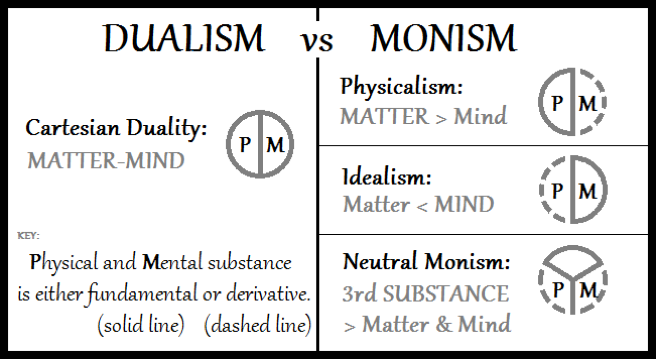

Cartesian dualism refers to a philosophical perspective that conceives the human body as two irreducible parts—the mind and the body (Blackburn 2008). Essentially, this philosophical view of the human essence separates the physical and palpable aspects of an individual from the symbolic and abstract elements.

Dualism in relation to monistic theories (Bonhomme 2016)

Background

The discussion of dualism dates back to the teachings of Plato, Aristotle, and schools of the Hindu philosophy (Broadie 2001). Plato’s depiction of dualism portrayed the soul as being imprisoned within the body and trying to escape to “the Forms,” which is essentially a permanent reality that makes things what they are. Aristotle’s perspective argued that intellect was part of the soul and the soul was part of the body, but the soul and body were not necessarily two separate entities. Descartes’s theory of dualism differed greatly from that of Plato and/or Aristotle, and led to a contemporary perspective that the body and soul are mutually exclusive entities that function independently.

Historical or Topical Context

Descartes’ ideas about Cartesian dualism have been a key player in the development of modern understandings of the mind-body problem that is frequently faced by the medical world (Scheper-Hughes and Lock 1987). The mind-body problem questions the relationship between the mental aspects of an individual and the physical aspects. The physical aspects are easily observed by the naked eye, whereas the mental components are not physically observable and are accessible only by the individual. The mind-body problem asks two key questions: (1) what make up the physical states and what make up the mental states and (2) how do these two parts interact? (Robinson n.d.) The mind-body problem has resulted in the emergence of several psychological theories of the relationship between the mental and the physical. Some of the most notable mind-body models include the biopsychosocial model, the mental-physical identity theory, and the organic unity theory. Each of these models attempt to explain and justify bodily behavior and functioning (Goodman 1991: 553-63).

Portrait of René Descartes (Skirry n.d.)

How it Relates to Politics of Health

The goal of many medical students is to establish the root cause of an ailment. In separating body and soul, Cartesian dualism encourages reductionism in the sense that the body is viewed as the “domain of science” (Scheper-Hughes and Lock 1987: 10). This relates to the politics of health because it medicalizes the biological body and disregards the influence of the psychological aspects of the mind. As a result, this emphasized attention towards the physical body and delayed the development of effective psychological treatment approaches. The understanding of how the mind and body relate and function either together or separately determines how mental illness is understood and addressed. Depending on how the body and mind are perceived to interact, different approaches may be taken to address both mental and physical ailments (Goodman 1991, 553-63).

Controversy/Perspectives

The mind-body problem that is associated with dualism has invited a range of differing perspectives and debates. Materialists, for instance, claim that mental states are merely misjudged physical states. Idealists, on the other hand, claim that physical states are created and interpreted by the mind. Dualists, as discussed throughout this paper, perceive both the physical body and the mind to be real and mutually exclusive. Descartes’ personal response to the mind-body problem was that the question itself comes from the misunderstanding that two elements of completely different nature are unable to function as a unit (Skirry n.d).

More modern versions of discussion stem from the late 1950s and early 1960s when Smart and Feigl re-introduced the mind-body problem and welcomed a debate and discussion that has continued over the decades (Kim 1998). One controversial opinion that emerged was that dualism was too reductive, leading many to argue that metaphysical relationships cannot and should not be reduced to a single explanation. The recognition that reductionism is an ineffective practice enables science to occur independently of physics, with no need to answer questions in one field in such a way that simultaneously answers questions in another field.

Before discussion of dualism, Christian perspectives of the body took precedence and viewed humans as spiritual beings whose illnesses were attributable to a supernatural force. When dualism hit the scene, however, the body was viewed through a more scientific and medical lens, leading to the development of the biomedical model (Mehta 2011:202-09). One issue with this, as previously mentioned, is that dualism led to the rise of reductionist treatment. When a doctor treats an illness, s/he prescribes a treatment to alleviate specific symptoms. Often, however, this approach neglects the psychological factors of the ailment and excludes the mind’s influence. It’s often argued that Cartesian dualism is too segregated (in the sense that the body and mind are viewed as two separate entities) and doesn’t recognize all of the contributing variables. However, many do agree that a dualistic approach to treating illness should be taken into consideration in order to address a range of influential factors in disease and illness (Switankowsky 2000: 567-89).

References

Blackburn, Simon. The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2008. Accessed March 26, 2017.

Broadie, Sarah. “Soul and body in Plato and Descartes.” Aristotle and Beyond 101 (2001): 101-12. Accessed March 26, 2017. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511551086.008.

Goodman, Aviel. “Organic Unit Theory: The Mind-Body Problem Revisted.” The American Journal of Psychiatry 148, no. 5 (May 1, 1991): 553-63. Accessed January 29, 2017. Periodicals Index Online.

Kim, Jaegwon. Mind in a physical world: an essay on the mind-body problem and mental causation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998.

Mehta, Neeta. “Mind-body dualism: A critique from a health perspectiveFNx08.” Mens Sana Monographs 9, no. 1 (December 2011): 202-09. Accessed January 29, 2017. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.77436.

Patterson, Sarah. “Review: Descartes’s Dualism.” Mind 116 (January 2007): 460-61. Accessed January 29, 2017. doi:10.1093/mind/fzm215.

Robinson, Howard. “Dualism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed January 29, 2017. Stanford University: Metaphysics Research Lab.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Margaret M. Lock. “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, no. 1 (March 1987): 6-41. Accessed March 26, 2017. doi:10.1525/maq.1987.1.1.02a00020.

Skirry, Jeremy. “The Mind-Body Distinction.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed January 29, 2017. http://www.iep.utm.edu/descmind/

Switankowsky, Irene. “Dualism and Its Importance for Medicine.” Theoretical Medicine 21 (2000): 567-89. Accessed January 29, 2017. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

« Back to Glossary Index