Definition of the Term

Chiropractic is defined as “a form of health care that focuses on the relationship between the body’s structure, primarily of the spine and function” by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (Ernst 545). It also has been described as “a healing art based on the principle that spinal misalignments cause diseases” (D. Johnson 206). The goal of chiropractic care is to “correct alignment problems, ease pain, and support the body’s natural ability to heal itself” (“Chiropractic,” Medline Plus). Chiropractors are the health care providers who perform manual corrections and adjustments to the spine or other parts of the body (D. Johnson 206; “Chiropractic,” Medline Plus). According to the American Chiropractic Association (or ACA), chiropractors are educated in the practice at accredited, four-year doctoral programs that includes classroom, laboratory, and clinical internship learning (“Patients”). In all fifty states as well as the District of Columbia, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, chiropractic is a licensed health profession (Ernst 545; Weiss and Lonnquist 253).

Approximately 60,000 chiropractors currently practice in the United States (D. Johnson 206; Weiss and Lonnquist 253). These chiropractors see an estimated 20 million people each year (Weiss and Lonnquist 253). Between $2.4 and $4 billion is spent on chiropractic care in the United States every year (Ernst 545). Like other medical doctors, chiropractors receive malpractice insurance coverage (D. Johnson 206). In 2005, a typical chiropractor received $1,000,000 worth of malpractice insurance coverage for the cost of about $4,000 a year (D. Johnson 206).

For an overview of chiropractic in video form, this 55 minute program on the history, philosophy, and practices of chiropractic care (as well as clips of an actual chiropractic session) is available through the streaming service Kanopy.

Historical Context

To understand current perspectives on chiropractic care, it is important to understand the history of the field. This encyclopedia entry will provide a brief overview of the history of the profession and its organization.

D.D. Palmer is considered the founder of the chiropractic discipline (Gaucher-Peslherbe 22; Ernst 544). Palmer founded chiropractic care out of his work as a magnetic healer, someone who adjusts the magnetic fields of the patient’s body (Batinic et al. 225). In the earliest known publication on chiropractic, Palmer described the practice as “a science of healing without drugs” (Ernst 544) and as “an outgrowth of magnetic healing” (Batinic et al. 226). Chiropractic history recounts September 18, 1895 as the birthdate of the field; on this date, Palmer adjusted displaced vertebrae in Harvey Lillard’s spine and in doing so, allegedly cured Lillard’s deafness (Batinic et al. 221; Ernst 546). Palmer’s research findings served as the foundational texts for this new form of healing practices (Weiss and Lonnquist 253). For more information on Palmer’s career, read this article.

As Palmer’s students developed chiropractic concepts and modified their own practices, they worked in isolation (C. Johnson 2). In the 1920s, many chiropractors “believed they had established their own form of science,” widening the gap between chiropractic care and conventional medicine (Ernst 545). There were more than 80 chiropractic schools in the United States by 1925 (Ernst 546). The isolation and competition among chiropractic leaders and among chiropractic colleges created “discontinuity and disruption in the development of the art, science, and philosophy of chiropractic” (C. Johnson 2).

At the beginning of the 20th century, chiropractors were one of the groups legally targeted as “irregulars” by members of the American Medical Association (C. Johnson 2). At this time, licensing laws did not allow the practice of medicine without a license; using this logic, chiropractors were arrested for practicing medicine without a license (C. Johnson 2). The first successful legal defense of chiropractic argued that practicing chiropractic “had a distinct, art, science, and philosophy” that distinguished itself from the allopathic practice of medicine (C. Johnson 2).

Figure 1: A cover of The Chiropractor. This cover announces that DD Palmer was arrested for practicing chiropractic care and labels him as “a martyr to his science.” (Source: C. Johnson)

In 1911, chiropractic terminology was standardized by the Universal Chiropractors Association for the purpose of legal cases (C. Johnson 3). The National Chiropractic Association (NCA) established the Mutual Corporation for Malpractice Insurance (NCMIC) in 1946 (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 17). The services of the NCMIC originally focused on the criminal defense of chiropractors charged with unlicensed practice (Keating, “Roots of the NCMIC” 41). As states began to enact chiropractic statutes, this legal program covered issues of malpractice and negligence (Keating, “Roots of the NCMIC” 39).

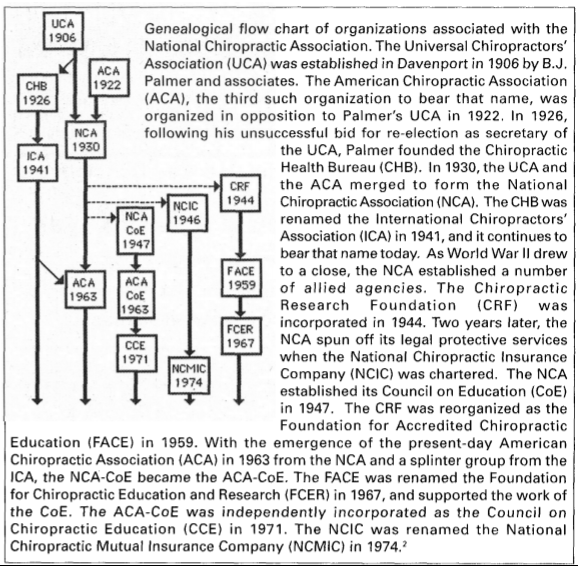

In 1963, the present-day American Chiropractic Association (ACA) formed, creating a constitution and bylaws for the profession (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 18). It is important to note that there have been other organizations within the chiropractic field with the same name. See the flow chart below to see a genealogical organization of chiropractic societies. Rather than specifying the boundaries of chiropractic, the ACA’s 1964 constitution contained a clause that left the scope of chiropractic care up to individual states (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 18).

Figure 2: A flow chart of chiropractic organizations from 1906-1974. All of these organizations are associated with the National Chiropractic Association. One can tell from this chart that the history of chiropractic societies involves many mergers and splits, and often, a repetition of organizational names. (Source: Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America”)

The newly formed ACA feuded with the International Chiropractors Association (ICA) over accrediting bodies for chiropractic schools (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 18). Because these two societies “sparred” with one another over accreditation for chiropractic education, recognition of this education on a federal level was delayed (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 18). In August of 1974, the Center for Credentialing and Education (CCE), which was supported by the ACA, received federal recognition as the accrediting bodies for chiropractic colleges (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 18). 1974 is suggested as a large turning point for chiropractic, as this was also the year that all fifty states gave legal recognition to chiropractors (Weiss and Lonnquist 255).

In the late 1980s, an effort to “generate a single, unified national membership society of chiropractors” was undertaken by Dr. Michael Pedigo, president of the ICA (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 17). An accommodation with the ACA almost merged the two societies together, but several board members of the ICA opposed the merger (Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 17).

Perspectives

Within the profession, there are differing perspectives on what type of healthcare it is (Ernst 545, Nelson et al. 2, Cooper and McKee 107). Some chiropractors wish the field to be “grounded in science and philosophy” while others wish for a more dogmatic, philosophical approach (C. Johnson 1). This encyclopedia article will discuss two perspectives: one that views chiropractic care as a part of regular medical care and one that views chiropractic as an alternative form of health practices.

Chiropractic as Alternative Health Practices

Although chiropractic services are “enthusiastically support[ed]” by many patients in the United States, others view it “as nothing more than successful quackery” (Weiss and Lonnquist 253). This perspective developed alongside the profession; in 1894, local newspapers wrote about Dr. Palmer as “a quack” that “deceived people” with his procedures (Batinic et al. 226).

The American Medical Association promoted this perspective throughout the middle of the 1900s, adopting a “chiropractic must die” slogan in 1922 and forming a 1963 Committee on Quackery that had the ultimate mission of eliminating chiropractic (Weiss and Lonnquist 255). Orthodox medicine saw chiropractic as “having little or no therapeutic value” and as a danger to patients (Weiss and Lonnquist 255).

Medical literature has seen a recent push to link chiropractic manipulation to “cerebral vascular accidents secondary to the dissection of the vertebral artery” (D. Johnson 206). These incidents are rare and efforts to increase their attention in medical literature are done to discount the legitimacy of chiropractic (D. Johnson 206).

The lexicon of chiropractic care works to separate this field from other traditional medicine practices (C. Johnson 4; Weiss and Lonnquist 254). Legal defense arguments used in the early 20th century have become engrained in the chiropractic field (C. Johnson 4). For example, terms like “analysis” (rather than diagnosis) and “care” (rather than treatment) were standardized within chiropractic and continue to draw a distinction between chiropractic and other forms of medicine that rely on terms like “symptoms” and “germs” to be the cause of disorders (C. Johnson 4; Weiss and Lonnquist 254).

The field continues to be critiqued for “not being self-critical enough or for not developing sound scientific and philosophical constructs” like other professions have (C. Johnson 1). Some chiropractors feel that if they “recognize historical origins,” they will “betray current concepts in chiropractic science and rational thought” (C. Johnson 5).

Growing interest in alternative medicine has increased chiropractic’s “opportunities in the medical marketplace” (Cooper and McKee 119). Although this growing interest increases chiropractic’s reach, it still relies on the notion of chiropractic being “alternative” medicine. One component of alternative medicine that chiropractic care demonstrates is the integration and importance of nutrition. Chiropractors, unlike most other medical doctors, is that they are heavily “trained in nutrition and many employ nutritional supplementation as part of their practice” (D. Johnson 206). Although they may use nutritional supplementation, chiropractors do not prescribe pharmaceutical medications; their training and licensing reflect this (D. Johnson 206).

Chiropractic as Regular Medicine

In 1987, a U.S. District Judge found the AMA (along with the American College of Radiology and the American College of Surgeons) guilty of conspiring “a boycott” and failing to justify their “patient care defense” (Weiss and Lonnquist 256). As a result of this ruling, chiropractors and other medical doctors are increasingly likely to work together on patient care, accepting and making referrals from one another (Weiss and Lonnquist 256). Chiropractors are trained to diagnose other medical conditions that are outside the scope of chiropractic and to refer these conditions to the appropriate medical providers (D. Johnson 206).

The Health Resources and Services Administration has supported chiropractic professionals in “establishing the clinical effectiveness of the therapies that they employ” (Cooper and McKee 108). The American Chiropractic Association designates chiropractors as “first contact” providers, meaning that they serve as a legitimate portal of entry into the health care system. In the majority of states and within the federal Medicare program, chiropractors are designated physician-level providers (ACA, “Patients”). Chiropractors commonly assist patients with the management of lower back and neck pain and tension headaches (D. Johnson 206; “Chiropractic,” Medline Plus). Effective management of these conditions has led to cost savings; these cost savings “led to the expansion of both government and third-party coverage for chiropractic care” (D. Johnson 206).

Prestige of the chiropractic field “is on the upswing,” partially because the “educational preparation for chiropractors has continued to be upgraded” (Weiss and Lonnquist 256). Education for chiropractic doctors “includes all the basic medical sciences” with a strong emphasis placed on anatomy and radiology (D. Johnson 206). The ACA argues that “educational and licensing requirements for doctors of chiropractic are among the most stringent” of all health care professionals.

Connection to the Politics of Health

One connection between chiropractic and the politics of health is through the concept of medicalization. Medicalization is defined by Peter Conrad, a medical sociologist, as “defining a problem in medical terms… or using a medical intervention to treat it” (3). In the case of chiropractic, it is not a specific symptom or spinal misalignment that has been medicalized; rather, it is the field of chiropractic as a whole that from its founding, has undergone and is continuing to undergo a process to gain “the power and authority of the medical profession” and thus, to be medicalized (Conrad 4).

Chiropractic is a unique case because the medicalization process occurred for the benefit of legal cases. Terminology, definitions, and concepts within the field of chiropractic care were not defined for clinical or laboratory research; rather, it was for use in the courtroom (C. Johnson 3). Claire Johnson, a professor of health sciences and the editor of the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities, argues that chiropractic terminology “was not generated from a proactive development from within [the] profession but from a reactive set of legal defense arguments” (4). Chiropractors who hold this viewpoint do not believe that their professional identity came from “internal formative developmental efforts” but rather, reactions to external pressures that forced the profession to unite and standardize (C. Johnson 4). This standardization has allowed chiropractic to begin the process of becoming a new medical category.

Another connection between chiropractic care and the politics of health is through the production of medical knowledge. Scientific and medical credibility refers to “the capacity of claim makers to enroll supporters behind their claims, to legitimate their arguments as authoritative knowledge, and to present themselves as [those] who can give voice” to science and medicine (Epstein 411). This credibility can be established through markers like academic degrees and institutional affiliations (Epstein 411). Questions of credibility are especially prominent in fields like chiropractic “that are marked by… degrees of controversy, uncertainty, and in particular, politicization” (Epstein 411).

By exploring the history of chiropractic, one can see the fight for credibility amidst the controversy of the profession. At the beginning of the 20th century, the AMA attempted to use their medical authority to discredit the credibility of chiropractors (C. Johnson 2; Keating, “Organized Chiropractic in America” 18). Through accredited professional colleges and professional societies like the ACA, those within the field of chiropractic are fighting to establish that they are the authoritative figures of chiropractic (C. Johnson 2; Weiss and Lonnquist 256). By doing so, they are “combining aspects of power, legitimation, trust, and persuasion” to join the system of medical authority in the United States (Epstein 411).

Works Cited

Batinic, Josip, Mirek Skowron, and Karin Hammerich. “Did American Social and Economic Events from 1865-1898 Influence D.D. Palmer the Chiropractor and Entrepreneur?” The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, vol. 57, no. 3, 2013, pp. 221-232.

“Chiropractic.” MedlinePlus, 18 October 2017, https://medlineplus.gov/chiropractic.html.

Conrad, Peter. “The Shifting Engines of Medicalization.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, vol. 46, 2005, pp. 3-14.

Epstein, Steven. “The Construction of Lay Expertise: AIDS Activism and the Forging of Credibility in the Reform of Clinical Trials.” Science, Technology, & Human Values, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 408-437.

Ernst, Edzard. “Chiropractic: A Critical Evaluation.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, vol. 35, no. 5, 2008, pp. 544-562.

Gaucher-Peslherbe, PL. “Daniel David Palmer: Alchemy in the Creation of Chiropractic.” Chiropractic History, vol. 15, no. 2, 1995, pp. 22-27.

Johnson, Claire. “Reflecting on 115 Years: The Chiropractic Profession’s Philosophical Path.” Journal of Chiropractic Humanities, vol. 17, 2010, pp. 1-5. PMC.

Johnson, David. “Chiropractic Care.” Encyclopedia of Aging and Public Health, edited by Sana JD Loue and Martha Sajatovic, Springer, 2008, pp. 206-207.

Keating, Joseph. “Organized Chiropractic in America: Approaching the Centennial, Part 2 of 2.” Dynamic Chiropractic, vol. 22, no. 12, 2014, pp. 17-20.

—. “Roots of the NCMIC: Loran M. Rogers and the National Chiropractic Association, 1930-1946.” Chiropractic History, vol. 20, n. 1, 2000, pp. 39-55.

“Patients.” American Chiropractic Association, 2017, https://www.acatoday.org/Patients.

Weiss, Gregory and Lynne E. Lonnquist. “Complementary and Alternative Medicine.” Sociology of Health, Healing, and Illness, Taylor and Francis, 2014, pp. 246-271.

« Back to Glossary Index