Definition and Background:

Worldwide, the pharmaceutical industry is worth over a trillion dollars (Jacobson 2014). In 2015, the median salary of CEOs of the 14 largest pharmaceutical companies in the United States was $18.5 million (Krantz 2016). This is 71% greater than the median salary of other S&P 500 executives (Krantz 2016). This being said, the industry relies on the constant addition of new drugs in the market to combat the rising cost of drug research and development (Jacobson 2014). A study looking at research and development (R&D) costs by Joseph A. DiMasi found an estimate “that total R&D cost per new drug is US$ 802 million in 2000 dollars” (DiMasi 2003, 180). This rising cost of drug development is understandably a problem for multi-national pharmaceutical companies. One way to combat this cost is to move research and development overseas (Glickman 2009). This is mostly done through the movement to less wealthy, developing countries (Glickman 2009). Since 2002, over 55% of drug trials for United States pharmaceutical companies have occurred outside the United States (Glickman 2009). In this entry, I will look at the reasons behind the movement of clinical drug trials to developing countries. I will also talk about the ethics surrounding the drug trials in research in the developing world.

Clinical research is defined as “a broad endeavor that involves investigators from a wide range of disciplines working with human subjects to characterize health and illness, and invent, test, and evaluate treatments” (Bevans 2011, 421). Clinical research is necessary for pharmaceutical companies to gather data on the efficacy and safety of the new drug (Jacobson 2014, 5). If you would like to know more about the actual phases and process of clinical trials, here is a link to the National Institute of Health and their explanation of the process behind clinical trials. Pharmaceutical companies are now more inclined to export the research, development, and manufacturing of the drugs to Contract Research Organizations (link to the CRO encyclopedia page) (Piachaud 2002). CROs allow pharmaceutical companies to “break outside existing market conditions” (Piachaud 2002, 83), and allow pharmaceutical companies to downsize, reducing their cost (Piachaud 2002). The research that CROs carry out was valued at over $5 billion in 1999 (Piachuad 2002). Another main reason for this outsourcing is due to the fact that “CROs claim to recruit patients quickly and more cheaply than academic medical centers” (Petryna 2006, 39). Pharmaceutical companies export their research for a multitude of reasons as described above, but CROs must still follow FDA regulations as would any research organization (Jacobson 2014).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees and regulates the pharmaceutical clinical trial industry in the United States, but struggles to regulate oversees trials (Jacobson 2014). The FDA “requires clinical trials conducted outside of the United States to be conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and adhere to the local regulations” (Jacobson 2014, 4). The local regulations in these developing countries usually come in the form of ethical review committees, but these review committees are usually weak or have ulterior interests when reviewing cases (Shehata 2017). These lax local regulations are a reason for movement of pharmaceutical clinical research to developing countries, but there are many other financial and scientific reasons (Shehata 2017).

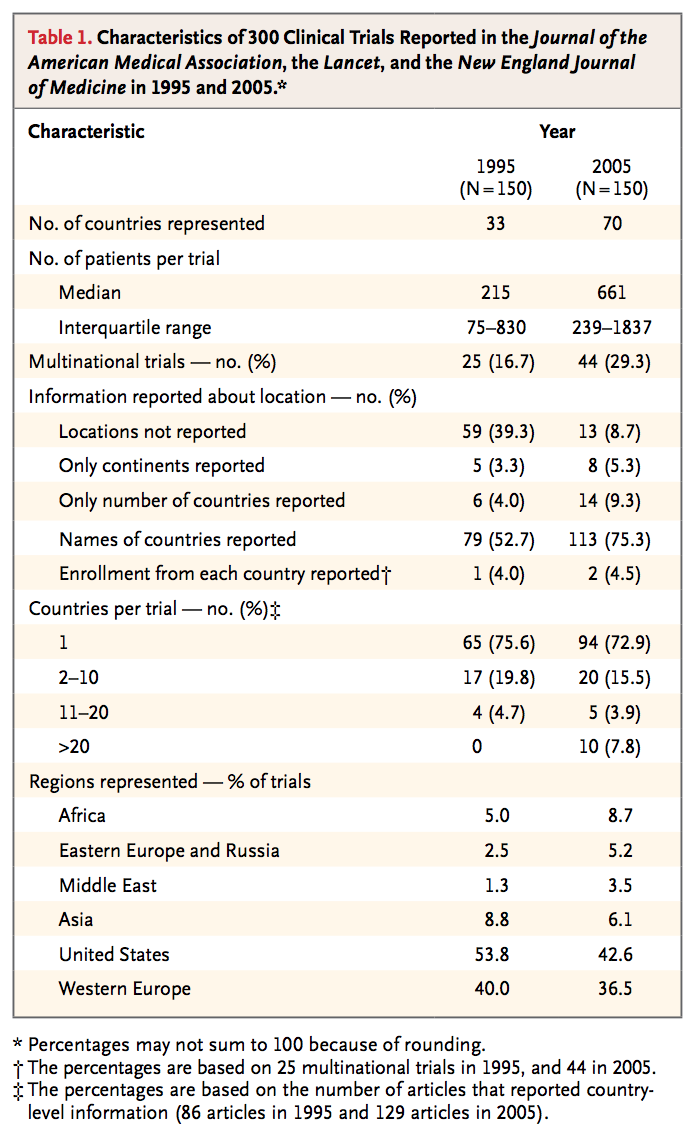

Source: Glickman, Seth W., et al. “Ethical and Scientific Implication of the Globalization of Clinical Research.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 360, no. 8, 19 Feb. 2009, pp. 816-823.

As the table illustrates above, vastly more countries are participating in clinical trials. According to Adriana Petryna, clinical research in low-income, developing countries has increased sixteen fold since the early 1990s (Petryna 2006). There are many advantages of conducting clinical research in developing countries. Financially, the cost of research is cheaper and the speed of research is faster as there is less oversight (Shehata 2017). The cost of research “in a first-rate academic medical center in India charges approximately $1,500 to $2,000 per case reports, less than one tenth the cost at a second-tier center in the United States” (Glickman 2009, 816). Due to the bureaucratic nature and vast regulatory systems in wealthy countries, research in developing countries, with less regulatory oversight, can be done significantly quicker (Glickman 2009). Almost half of the $802 million cost for a new drug comes from the time in which the trial would take within the United States (DiMasi 2003). By exporting the trials to developing countries, this cost can be cut down (Glickman 2009).

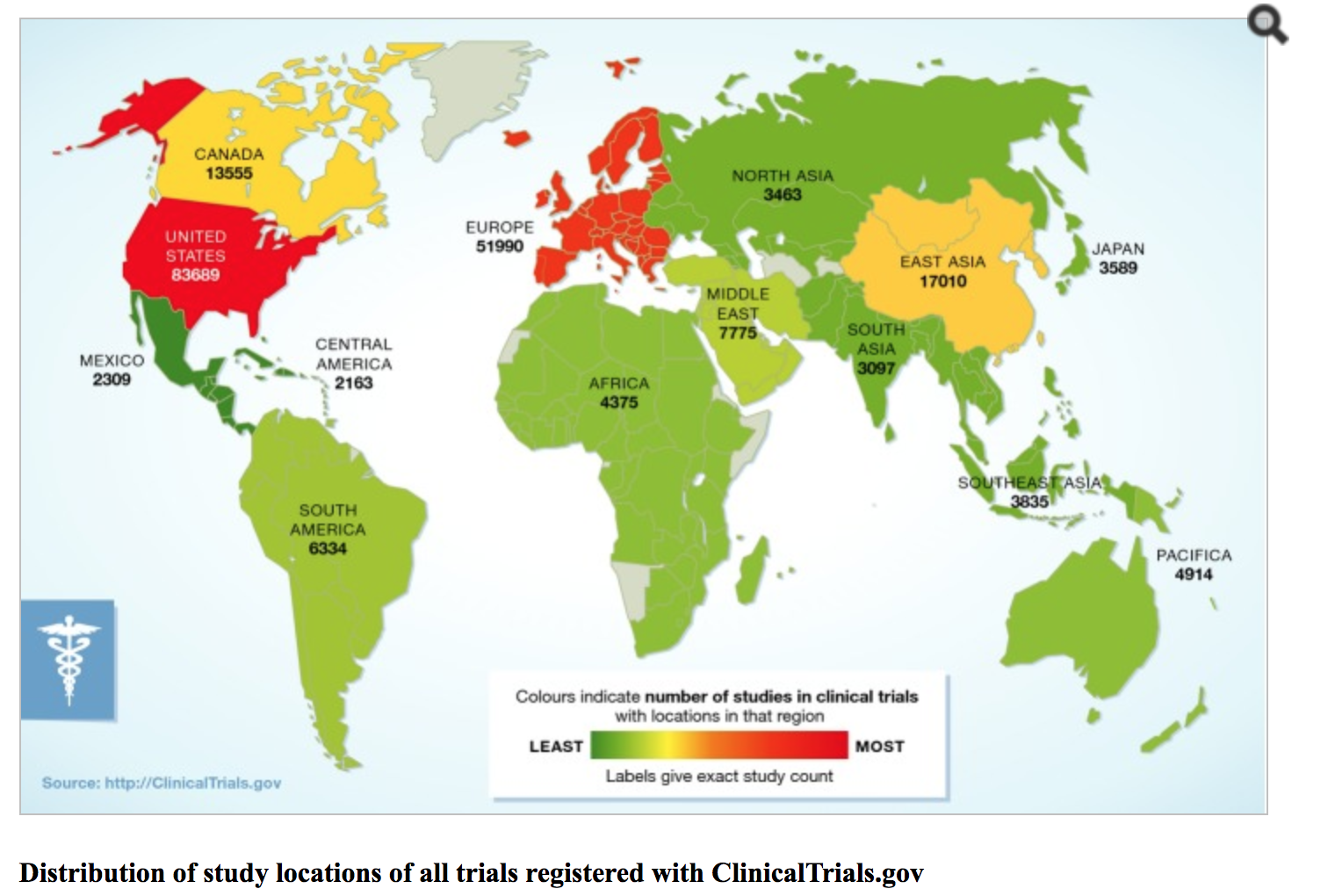

Another factor in transporting research overseas is the demand of human subjects. In 2006, the number of clinical projects worldwide was predicted to be almost 20,000 new trials per year (Petryna 2009), and the availability of subjects to be tested in the United States is decreasing (Petryna 2006).

Source: Weigmann, Katrin. “The Ethic of Global Clinical Trials.” Science & Society, vol. 16, no. 5, 7 Apr. 2015, pp. 566-570.

Source: Weigmann, Katrin. “The Ethic of Global Clinical Trials.” Science & Society, vol. 16, no. 5, 7 Apr. 2015, pp. 566-570.

As the graph, courtesy of Katrin Weigmann, shows the potential of the human subject in the developing world of South Asia and Africa (Weigmann 2015). It also displays how used up the subjects are in the United States and Europe, making these areas unfit for new clinical trials (Weigmann 2015). This factor along with the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH), which set standards for safety and quality of research worldwide, created a system in which international data could be send to the FDA for approval (Petryna 2006). The ethics of whether these practices are acceptable or put people at harm will be discussed in the “Perspectives and Controversies” section of the entry.

Historical Context

The movement towards globalization of clinical trials began in the mid-1970’s (Petryna 2006). This occurred when the use of prisoners as test subjects was brought into the light, and was thereafter limited in its use (Petryna 2009). The use of prisoners in the United States was so incredibly vast that “an estimated 90 percent of drugs licensed in the United States prior to the 1970s were first tested on prison populations” (Petryna 2009, 23). By 1980, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services had severely limited the use of prisoners in clinical drug trials in the United States (Petryna 2009). After this development, clinical drug trials increasingly outsourced to countries like England and Sweden (Petryna 2009).

Clinical drug trials in the developing world started to garner attention in 1997 when the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health funded and developed trials of an FDA approved drug, AZT, to be tested on women with HIV in Thailand, the Dominican Republic, and a number of African countries (Roman 2002). In the trial, half of the women got the placebo and half got the AZT treatment (Roman 2002). This study came to bare quite a debate of international ethical practices within drug trials in a developing world setting as because of the placebo given to half the women, “more than 1,000 babies contracted the AIDS virus” (Roman 2002, 444). In the end, the trials in Africa were shut down in 1998, but the debate revolving around ethics in the medical research community continued (Roman 2002). These trials, especially being the responsibility of the U.S. government, played the historical, starting role in the discussion of ethics in clinical research in terms of developing countries, as it became clear that regulations in place from the Nuremberg Code were not always clearly followed (Roman 2002).

Perspectives and Controversy

Clinical research in developing countries can be viewed as ethical or unethical with variation to the necessity of the study. Ethics are the basis of clinical research (Angell 1997). There are many standards to reach when considering ethics in medical research, starting with the International Conference on Harmonization and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines that are situated within it (Petryna 2006). This includes the implementation of institutional review boards for investigators, along with the goal of “ensuring and assessing the safety and quality of testing procedures for experimental compounds” (Petryna 2006, 38). Although, in many developing countries, there is a growing concern that there is a lack of ethical oversight (Glickman 2009). This side of the argument may focus on “the medical and social relevance of these studies; the quality of informed consent procedures and the freedom of choice of individuals” (Lorenzo 2009, 111).

The FDA has some responsibility to uphold these standards in research done outside the United States, but it is hard to export U.S. standards to other countries (Weigmann 2015). All of these concerns lead to the increased risk of the human subject during clinical trials in developing countries (Jacobson 2014). The lack of oversight that local regulatory committees can provide hinders the protection that subjects in developing countries can receive (Jacobson 2014). Without regulation, it is easy to see how CROs and trans-national pharmaceutical companies may be able to bend the rules, and give in to “the strong temptation to subordinate the subjects’ welfare to the objectives of the study” (Angell 1997, 848). Without proper regulation in the country that the trials are being conducted, many researchers believe that an individual’s right are at risk. This would be no different than the individuals’ lives at risk in the HIV trial in the developing world in the late 1990’s, where it could be argued that the trials were unethical (Roman 2002).

Another issue that this side may argue is that in other cultures the idea of individual autonomy may be different, which renders individual informed consent unusable (Diallo 2005). Dapa A. Diallo argues that community permission, especially in African countries, is crucial in determining individual decision making (Diallo 2005). This decision-making process “could enhance the individual informed consent process, perhaps improve enrollment, and decrease adverse effects if the research on community values” (Diallo 2005, 255). Individual informed consent is tough due to the lack of proficient health care resources and the likelihood that pressure to enroll could play a larger role than the interests of the actual patient (Angell 2017). Another issue involving informed consent is the cultural and conceptual barriers that the trial may provide to an individual (Angell 2017). Poor individuals with no education in developing countries may struggle to understand the research, and this will not allow them to give true individualized informed consent (Angell 2017). A lack of understanding of the research may lead to the misconception of their own disease, and this can coerce an individual into saying yes to the researchers (Lorenzo 2010). The individuals who participate in the study may also not understand that once the trial is over, the medication they received may not be available to them due to high medical costs, which many researchers may view as unethical (Zumla 2002).

The other side of this argument focuses on the necessity that is clinical trials in developing countries. Katrin Weigmann states that the trials themselves are not unethical, and argues that clinical research can be done in a way in developing countries that is ethical (Weigmann 2015). Weigmann gives the example of trying to test a malaria vaccine in Europe or North America; there would simply not be enough participants to make the trial work (Weigmann 2015). This is to state that it really is necessary to conduct this research (Weigmann 2015). Weigmann also talks of the FDA and their strict regulations that make research in the United States almost impossible due to the time and money that a trial costs in the United States (Weigmann 2015). This is not to say that ethics should be thrown out the window, but the community partnerships that are formed through clinical research in the developing world may answer “questions about the safety and efficacy of drugs and devices that are of interest through the world” (Glickman 2009, 818). Fostering relationships between researchers in different countries, not only helps the populations in developed worlds, but also the populations participating in the research (Glickman 2009).

Another perspective is that this may be the only way in which many of these people get proper healthcare may be through clinical trials. Many of the diseases that affect the developed world, such as cardiovascular disease, are increasingly impacting the developing world (Glickman 2009). Dr. Seth Glickman argues that when the problems that are researched occur in both worlds, then this research must occur for the good of both those in developed worlds, but also those in the developing world (Glickman 2009). Glickman also explains that this research should not only focus on the diseases that straddle both worlds, but also those that affect those in the developing world disproportionately, such as tuberculosis (Glickmann 2009). As disease becomes more international, clinical research must become international to be able to provide care for those who may not receive it otherwise (Shehata 2017).

Politics of Health

I believe that clinical research can be related to two forms of citizenship, therapeutic and pharmaceutical. To start, therapeutic citizenship can be defined as “claims made on a global scale on the basis of a therapeutic predicament” (Nguyen 2004, 126). This therapeutic citizenship expands biological citizenship through a therapeutic economy and biopolitics (Nguyen 2004). In the case of developing countries, clinical research is a form of bio-politics (Nguyen 2004). Clinical trials in developing countries is related to therapeutic citizenship because these trials in developing countries have provided the test subject with a form of therapy for their respective problem, and the globalized approach of pharmaceutical companies and CROs has created a ground for therapeutic citizenship in the developing world (Nguyen 2014). Those with access to these trials may “become increasingly vocal in demanding access to treatment for their condition, setting a global stage” (Nguyen 2014, 141). The pharmaceutical industry is continuing to shift their trial locations to low and middle-income settings in the developing world (Shehata 2017), and the more this occurs, the more a precedent will be set for therapeutic citizenship.

Another form of citizenship that may be affected by clinical trials in the developing world is pharmaceutical citizenship, defined by Dr. Stefan Ecks as a form of biological citizenship that centers around how legal citizenship determines the right to pharmaceuticals and around if the aspect of taking pharmaceuticals grants citizenship to individuals who may not be considered citizens already (Ecks 2006). Another aspect of pharmaceutical citizenship is the global pharmaceutical citizenship that may be offered through interaction with clinical trials (Ecks 2006). In Ecks’ model, those targeted and most likely to be affected by pharmaceutical citizenship are “low-class women or migrant workers” (Ecks 2006, 244). Clinical trials in developing countries is related to pharmaceutical citizenship because those entitled to pharmaceutical citizenship are the same individuals that are targeted by transnational pharmaceutical companies (Shehata 2017). The problem with subjects in the United States is that their affluence leads them to be taking too many drugs to be in clinical trials (Petryna 2006). This is not the case for those in developing countries, the low-income subjects that are targeted by the pharmaceutical industry are those that lack citizenship already (Ecks 2006). By participating in clinical trials, an individual gains the right to affordable medication and therefore may be offered a form of biological citizenship through pharmaceutical citizenship.

References

Angell, Marcia. “The Ethics of Clinical Research in the Third World.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 337, 18 Sept. 1997, pp. 847-849.

Beavans, Margaret., et al. “Defining Clinical Research Nursing Practice: Results of a Role Delineation Study.” Clinical and Translation Science, vol. 4, no. 6, Dec. 2011, pp. 421-427.

Dapa, Diallo A., et al. “Community Permission for Medical Research in Developing Countries.” Clinical Infectrious Diseases, vol. 41, no. 2, 15 Jul. 2005, pp. 255-259.

DiMasi, Joseph A., et al. “The Price of Innovation: New Estimates of Drug Development Costs.” Journal of Health Economics, vol. 22, no. 2, Mar. 2003, pp. 151-185.

Ecks, Stefan. “Pharmaceutical Citizenship: Antidepressant Marketing and the Promise of Demarginalization in India.” Anthropology & Medicine, vol. 12, no. 3, Dec. 2005, pp. 239-254.

Emanuel, Ezekiel J., et al. “What Makes Clinical Research in Developing Countries Ethical? The Benchmarks of Ethical Research.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 189, no. 5, 2004, pp. 930–937.

Glickman, Seth W., et al. “Ethical and Scientific Implication of the Globalization of Clinical Research.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 360, no. 8, 19 Feb. 2009, pp. 816-823.

Krantz, Matt. “Drug Prices are High. So are the CEOs’ Pay.” USA TODAY, 26 Aug. 2016.

Jacobson, Michael William. “Clinical Trials in Developing Countries.” Law School Student Scholarship, 2014, pp. 1-30.

Lorenzo, Cláudio., et al. “Hidden Risks Associated with Clinical Trials in Developing Countries.” Journal of Medical Ethics, vol. 36, 2010, pp. 111-115.

Nguyen,Vinh-Kim. “Antiretroviral Globalism, Biopolitics, and Therapeutic Citizenship.” Ong/Global Assemblages, vol. 21, no. 4, 204, pp 124-144.

Petryna, Adriana. “Globalizing Human Subjects Research.” Global Pharmaceuticals: Ethics, Markets, Practices, edited by Adriana Petryna, Andrew Lakoff, and Arthur Kleinman, Duke University Press, 2006, pp. 33-61.

Petryna, Adriana. When Experiments Travel: Clinical Trials and the Global Search for Human Subjects. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Piachaud, B.S. “Outsourcing in the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Process: An Examination of the CRO Experience.” Technovation, vol. 22, no. 2, Feb. 2002, pp. 81-90.

Roman, Joanne. “U.S. Medical Research in the Developing World: Ignoring Nuremberg.” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, vol. 11, no.2, Spring 2002, pp. 441-460.

Shehata, Sherif M., et al. “Current Review of Medical Research in Developing Countries: A Case Study for Egypt.” International Development, edited by Dr. Seth Appiah-Opoku, 26 Apr. 2017, pp. 40-64.

Stone, Kathlyn. “Contract Research Organizations (CRO) – Definition” The Balance, 19 Feb. 2017.

Weigmann, Katrin. “The Ethic of Global Clinical Trials.” Science & Society, vol. 16, no. 5, 7 Apr. 2015, pp. 566-570.

Zulma, Alimuddin., et al. “Ethics of Healthcare Research in Developing Countries.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 95, no. 6, Jun. 2002,

« Back to Glossary Index