Toria Tomasek and Sarah Whitaker

Cochlear Implants:

A cochlear implant is a device that someone who has significant trouble hearing can use. The device is meant to help someone who is deaf or severely hard of hearing detect some representation of hearing in their environment; however, a cochlear implant cannot create “normal hearing” (www.nidcd.nih.gov).

While the first cochlear implant was not implanted until 1961 by doctors William House and John Doyle, medical technology had been approaching this point for quite some time (Mudry et al. 2013 146). In fact, attempts to electrically stimulate the ear in order to cause a form of hearing have been recorded as early as 1748 (Mudry et al. 2013 447). For example, in 1790, Alessandra Volta connected two piles of batteries with a wire and two conductive rods. Sticking each of the rods in his ears, Volta heard a boom-like noise in his head. This instance represents one of the first attempts to use electrical stimulation to mimic hearing (Wilson et al. 2008 4). The technology of cochlear implants has been improving since its first use, but studies suggesting the efficacy of cochlear implants first occurred around the mid-1970s, making cochlear implants a relatively new technology (Mudry et al. 2013 451).

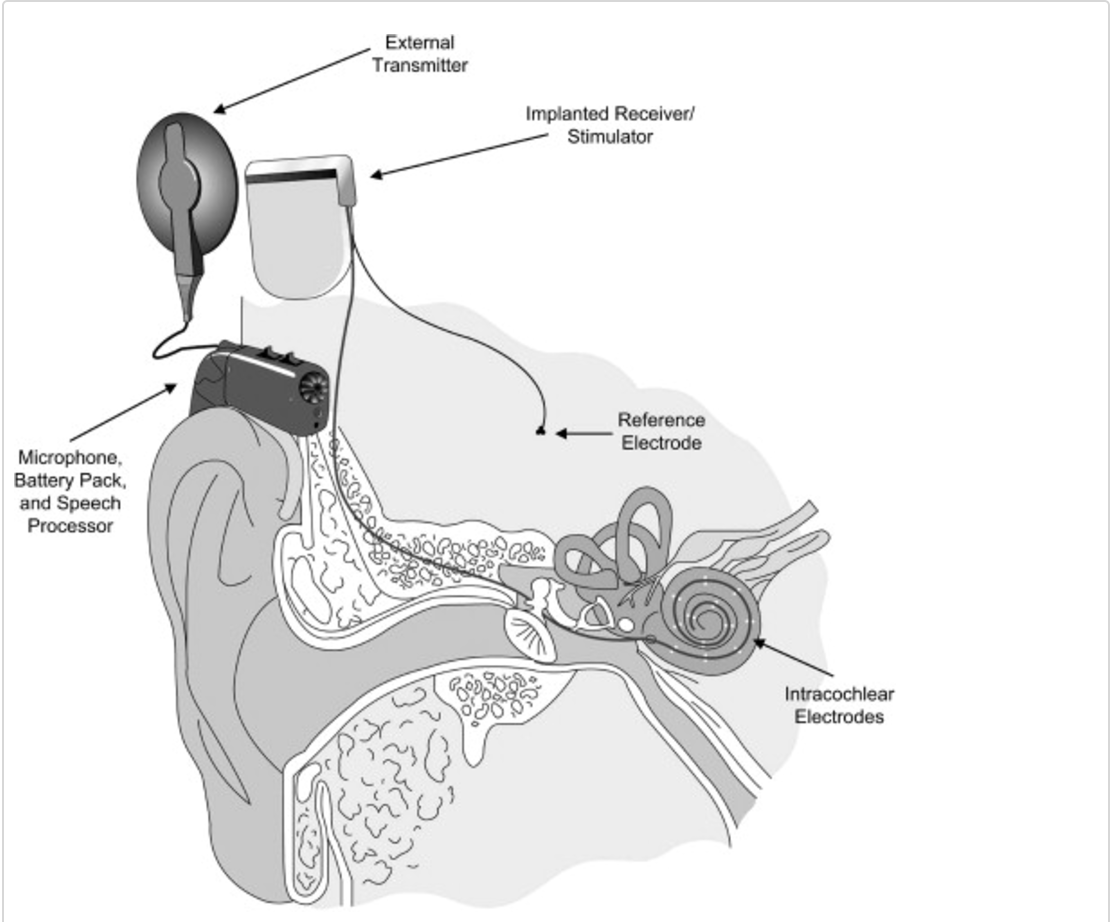

Cochlear implants have several complex components (shown in the below diagram) (Wilson et al. 2008 6) which can be put into two different groups: the internal portion and the external portion. The internal portion is an electrode array which collects data from the external portion and turns the data into a signal that the brain and nerves can understand. This portion of the device is surgically implanted into the ear. The external portion rests outside of the body, behind the ear. This portion is made of a microphone, a speech processor, and a transmitter, and a receiver/stimulator. The microphone detects sounds from the person’s environment and send those sounds to the speech processor. The speech processor organizes and selects these sounds and sends them in a signal to the transmitter and receiver/stimulator. There, the signal is turned into several electrical impulses which are finally sent to the internal portion of the implant (www.nidcd.nih.gov). This processes does not amplify sound like a hearing aid, but it acts to replace processes that a damaged ear can no longer perform. These devices work to send signals directly to the brain.

Part of the problem with cochlear implants, as mentioned before, is that they only give an approximation of what hearing is like, they cannot interpret sounds the same way that people without damaged ears do. This makes it especially difficult for people who were born deaf because now they need to learn how to interrupt the signals they are able to detect, and they also need to learn how to speak. Since, they do not hear normal sounds, learning to make those normal sounds become much more difficult. For these reasons, cochlear implants have been proven much more effective in people who started out able to hear and then lost it, compared to people who were born without hearing (Elliot 244). This leads to a bigger controversy in the Deaf community.

While many individuals today are considered deaf due to impaired hearing, a separate community among that population has recently emerged, the Deaf community. This group of individuals believe that their deafness is not a disability, but rather a new identity and culture. According to this community, cochlear implants are incredibly harmful to their Deaf culture which they believe must be preserved (Tucker 1998). A large portion of deaf children are born to hearing parents, and these parents are in charge of making decisions about the child’s future from a young age. Cochlear implants can be surgically placed in a child from a young age and often times the child is unable to have or make an opinion (Ramsey 79). However, having or not having these implants has a much bigger impact on the child’s life than just them being able to hear or not. “[T]he choice for or against a cochlear implant looks less like a choice about a surgical procedure than a choice about what country or region to live in, what church to attend, what language to speak at home. The debate about cochlear implants is a debate about what sort of person a child will grow up to be.” (Elliot 245) Most of the time, the parents are just trying to do what is best for their child, but people have different opinions on what can be considered the best. The Deaf community thinks that cochlear implants are not necessary and that these implants are leading to the demise of their culture. In addition, the Deaf community does not think of themselves as disabled and they do not want to hear because being able to hear will alienate them from their community. They feel like cochlear implants, or any device that enables some type of hearing, is leading to the demise of their culture. However, hearing parents often think that the way for their children to be most successful is if they are able to hear, even if it is limited. They think that by fixing this physical problem, they can improve their child’s future quality of life. Both sides of this argument have valid points, but they differ so much because of a much deeper stance on what is considered “normal” or “healthy.”

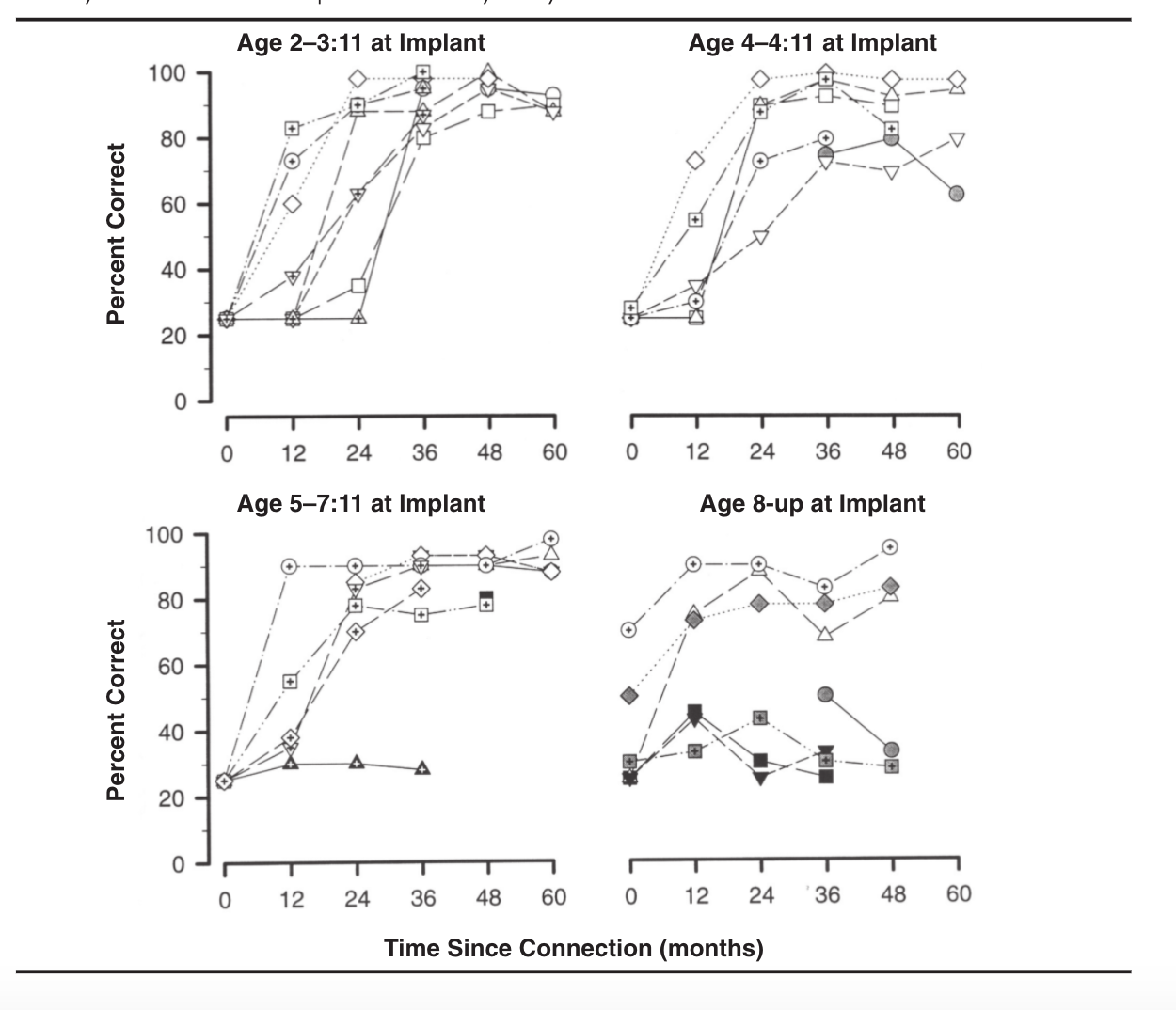

Despite any debate surrounding the ethics of cochlear implants, especially among children, the effectiveness of cochlear implants on improving speech recognition cannot be disputed. One study from 1997, when cochlear implants weren’t even at the level of technological advancement which they are today, proves this. The speech perception of thirty four children—all of whom received a cochlear implant and all of whom vary in terms of when they received their implant, how often they use it, and the cause of their deafness—was analyzed pre-operatively and annually using various recognized speech perception tests. Essentially, this study tested the long-term benefits of cochlear implants (Fryauf-Bertschy 1997 184). The data pointed out two key trends: first, age of implantation has a large effect on long-term effectiveness of cochlear implants; second, despite individual variances, cochlear implants generally cause a dramatic improvement of speech perception. The figure below, the results from the Vowel Perception Test, displays both of these trends (Fryauf-Bertschy 1997 191). Further, despite the fact that age of implantation has a pronounced effect on how much cochlear implants improve recognition of speech, one study of cochlear implants among elderly populations shows that giving significantly older individuals cochlear implants still greatly improves their quality of life (Orabi et al. 2006).

As for the future of cochlear implants, many professionals suggest that the technology has already advanced so far that major shifts in how cochlear implants are implanted and used will not occur. However, the technology will continue to be fine-tuned to increase user satisfaction and to enhance the positive effects of CIs (Wilson et al. 2008).

This relates to the politics of health in many different ways. First, it is right at the center of the idea of what is considered “normal” or healthy,” and who creates these notions. It also deals with the idea of institutions and how they affect these ideas of normalcy. The medical community views being deaf as a physical disability, yet the Deaf community sees it as just another part of their lives. This debate can be discussed in the terms of biological citizenship, and about the barriers to being able to claim a position in a certain community or organization. Lastly, it is relevant to the idea of medicalization; some communities want to medicalize being deaf as a disability and treat it as such, while the Deaf community wants to demedicalize it. These ideas all have the potential to influence policymaking because the debate on whether or not to use cochlear implants really boils down to a debate of whether or not deafness is a disease, which affects insurance coverage, disability payments, etc.

Resources:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Accessed on March 21, 2017. Cochlear Implants. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/cochlear-implants

Elliott, Carl

Bringing up Baby. Better than Well Ch. 10.

Fryauf-Bertschy, H., Tyler, R. S., Kelsay, D. M. R., Gantz, B. J., & Woodworth, G. G. (1997). Cochlear Implant Use by Prelingually Deafened Children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. Retrieved from http://www.jslhr.pubs.asha.org

Mudry, A., & Mills, M. (2013). The Early History of the Cochlear Implant. The Journal of the American Medical Association. Retrieved from http://www.jamanetwork.com

Orabi, A. A., Mawman, D., Al-Zoubi, F., Saeed, S. R., & Ramsden, R. T. (2006). Cochlear implant outcomes and quality of life in the elderly: Manchester experience over 13 years. Clinical Otolaryngology. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

Ramsey, Claire L.

- Ethics and Culture in the Deaf Community and Response to Cochlear Implants. Seminars in Hearing. Vol (21). No. 1

Tucker, B. P. (1998). Deaf Culture, Cochlear Implants, and Elective Disability Authors. The Hastings Center Report. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

Wilson, B. S., & Dorman, M. F. (2008). Cochlear implants: A remarkable past and a brilliant future. Hearing Reserach. Retrieved from ScienceDirect database.

« Back to Glossary Index