Colin Slaymaker

Down Syndrome

Definition and Background

Down Syndrome is a chromosomal disorder in which people have an extra copy of chromosome 21 (Megarbane 611). Those with Down Syndrome have shared facial features, such as small, flattened heads in infants. Furthermore, individuals with Down Syndrome have smaller ears, eyes, mouths, and noses and are often ailed by hypotonia, which involves low muscle tone or muscle strength (Penna 299). People with Down Syndrome are also subject to cognitive deficits and greater likelihood of some diseases. However, these impairments span a wide range, with most of those affected falling into “the mild to moderate range of cognitive disability,” (Penna 299). Approximately 1 in every 700 newborns in the world is born with Down Syndrome, making it the most widespread form of cognitive disability in the world (Megarbane 611). A link to a video demonstrating tests of cognitive and motor deficits in children with Down Syndrome is present here https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/hmdvid/hmdvid-9511390/hmdvid-9511390.mp4. In the video, the child struggles to stand on his own, stack blocks, and imitate a nurse’s actions. Furthermore, one can see the typical facial features of a child with Down Syndrome.

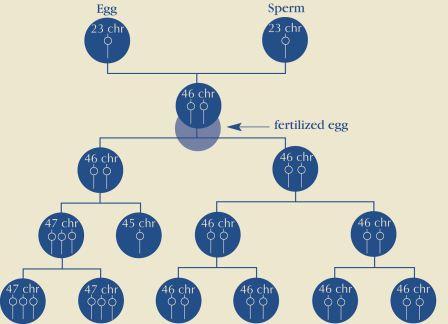

Three types of Down Syndrome exist, with Trisomy 21 being the most prevalent. Trisomy 21 accounts for 95% of cases of Down Syndrome, and occurs when individuals have 47 chromosomes in each cell in their body (“What Causes Down Syndrome?”). Most humans have 46 chromosomes in their cells, one copy of chromosomes 1-23 that is inherited from the female and another copy of chromosomes 1-23 that are inherited from the male. Trisomy 21 most often occurs by the mechanism of nondisjunction in the gametes, or sex cells, of the parents (“What Causes Down Syndrome?”). Nondisjunction occurs during cell division. In the process of meiosis, which leads to the creation of gametes, cells normally divide to produce four different sex cells, each of which has 23 chromosomes. In the case of nondisjunction, these divisions do not occur evenly, resulting in some cells gaining differing numbers of chromosomes (“What is Down Syndrome?”). For instance, through meiosis, one gamete may receive 22 chromosomes, missing its copy of chromosome 21. On the other hand, one gamete may receive 24 chromosomes, including two copies of chromosome 21. An animated video detailing the differences between normal cell division and nondisjunction in meiosis is linked here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EA0qxhR2oOk. When the gamete with 24 chromosomes fuses with another during fertilization, the resulting cell has three copies of chromosome 21, causing Down Syndrome (“What is Down Syndrome?”). The physical and cognitive defects of Down Syndrome are due to this extra genetic material present in chromosome 21. The expression of these extra genes ultimately leads to the defects (“What is Down Syndrome?”).

Translocation, which accounts for approximately 4% of all cases of Down Syndrome, occurs when a portion of chromosome 21 breaks off during cell division, normally attaching to another chromosome (“What is Down Syndrome?”). It typically attaches to chromosome 14, and though this form of Down Syndrome does not lead to 47 chromosomes present in the cell, it is the extra portion of chromosome 21 that exists that causes the disorder (“Three Types”). Mosaicism, which accounts for the other 1% of cases, occurs when nondisjunction takes place after the initial fertilization and creation of the embryo.

As the embryo divides, nondisjunction occurs in one, but not all divisions, leading to some cells with 47 chromosomes and some with 46 (“Three Types”). Despite that these 47 chromosomes are not present in every cell throughout the body, the fact that some extra genetic material exists causes Down Syndrome in these instances. Images detailing the mechanisms of mosaicism and trisomy 21 are available below.

FIGURE 1: The Mechanisms of Trisomy 21 (top) and Mosaicism (bottom) (“What is Down Syndrome?”)

Today, there are no known environmental factors that cause Down Syndrome (“What is Down Syndrome?”). Only a correlation between maternal age and Down Syndrome has been discovered, and women over age 35 are at a much greater risk (“What is Down Syndrome?”). More information on the likelihood of having a baby with Down Syndrome can be found on the National Down Syndrome Society website linked here https://www.ndss.org/about-down-syndrome/down-syndrome/.

Historical Context

Down Syndrome has affected people for many years, with the first proof of the condition dating back to 2,500 years ago in artifacts found associated with the Tomaco-La Tolita Culture (Megarbane 611). However, no clinical description of Down Syndrome was published until 1886 by John Langdon Down, who the condition is named after (Megarbane 611). Down distinguished children with Down Syndrome from other children with cognitive disabilities. In differentiating these children from others, he referred to them as Mongoloids and their condition as Mongolism due to the fact that “these children looked like people from Mongolia,” (Megarbane 611) due to their slanted eyes and other facial characteristics. The term mongolism is considered derogatory today (Penna 299). It was not until 1959; however, that French physician Jérôme Lejeune discovered the chromosomal basis for Down Syndrome (Megarbane 612).

Treatment of individuals with Down Syndrome has changed radically over the years. In the United States, the first hospital targeted towards those with mental disorders, Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, VA, opened in 1773 (“Down Syndrome Human”). Institutionalization of those with Down Syndrome became a trend by the 1830s, as “many states had opened training schools and institutions where people with disabilities were to receive specialized instruction,” (Penna 299). Though these centers were opened in good will and to help those with mental development disabilities, these institutions largely failed to achieve this mission. Institutionalization led to the isolation of individuals with Down Syndrome from the greater community, further stunting their cognitive development and leading to abuse (Penna 299). The institutionalization movement continued throughout the early 1900s, as those with Down Syndrome were one of the largest populations in these centers (Cooley 234). Unfortunately, the eugenics movement coincided with the institutionalization movement. Early in the twentieth century, the “eugenics movement brought a change in the objective of institutional placement from custodial care and support to one of protecting society from the perversities of behavior and genetics,” (Cooley 234). This movement stemmed from beliefs that those with cognitive disabilities were responsible for the problems of society. Furthermore, the eugenics movement encouraged that these “burdens to society” could be eliminated through complete segregation or even sterilization (Cooley 235). Some physicians even refused to operate on seriously ill patients with Down Syndrome due to this belief (Cooley 233). In 1907, Indiana was the first state to legalize sterilization practices and was followed by many other states (“Down Syndrome Human”). These practices were controversial and ultimately went to the Supreme Court. In the 1927 case Buck v. Bell, it was ruled that sterilization of those with Down Syndrome was permissible, as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes described, “since society could call on citizens to sacrifice their lives in times of war, it could demand that people “who already sap the strength of society” could be forced to make lesser sacrifices,” (Penna 299). It was not until after World War II, when the atrocities of the eugenics practices carried out by the Nazis became globally recognized that such eugenics movements began to slowly die out (Cooley 235).

The deinstitutionalization movement began in the 1950s and 1960s, with children with Down Syndrome staying with their families more often than not by the 1970s (Penna 299). This movement was aided by the passage of Public Law 94-142, which, when passed in 1977, “ guaranteed free, equal, and appropriate educational opportunities in the least restrictive environment for all individuals with handicaps from age 3 to age 22,” (Cooley 234). Furthermore, the passage of this law helped lead to the genesis of many family support and therapy programs for children younger than 3. These programs helped integrate those with Down Syndrome into society and were a driving force in further separating those with Down Syndrome from institutions (Cooley 234). The deinstitutionalization movement helped lead to the creation of Down Syndrome advocacy organizations, such as the National Down Syndrome Congress and the National Down Syndrome Society, created in 1973 and 1979, respectively (Penna 299). These organizations were key in enabling those with Down Syndrome to speak out for themselves and actively pursue full lives. By the 1980s, institutionalization was no longer an option (Cooley 233), and the health care of those with Down Syndrome had improved remarkably. In 1965, half of children with Down Syndrome died by age five, but by the end of the 1980s, around 80% survived past age 30 (Cooley 233). By the 1990s, children with Down Syndrome had many more opportunities to live full lives and to contribute to society as students, employees, and in many other areas (Cooley 233). Today, individuals with Down Syndrome are eligible for multiple government benefits from The Social Security Administration (“AST”). These benefits include Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (“AST”), both of which provide payment and medical coverage. SSI individuals are eligible for Medicaid, and SSDI individuals receive Medicare benefits automatically after two years of benefits (“AST”). Individuals with Down Syndrome are also eligible to apply for state-run Medicaid waivers (“AST”). Despite the fact that treatment of those living with Down Syndrome has improved, the technology of amniocentesis has brought up worries that modern eugenics have emerged. As amniocentesis allows a physician to predict if a fetus has Down Syndrome, there has emerged a “high termination of fetuses that have tested positive for Down Syndrome,” (Dixon 3).

Controversy/Perspectives

As the technology of amniocentesis has developed, worries have emerged about modern day eugenics relating to Down Syndrome. Amniocentesis is a genetic test that samples the amniotic fluid of a developing fetus. With this fluid, it can be determined whether or not a fetus has Down Syndrome (“Amniocentesis”). Therefore, women who undergo amniotic fluid testing have knowledge of whether or not their baby has Down Syndrome early in the pregnancy, enabling them to make decisions about abortion with this information in mind. Prenatal counseling is meant to be non-directive (Dixon 4). In other words, prenatal counseling is meant not to give targeted advice or to encourage certain decisions, but to be a system of support. In her book Testing Women, Testing the Fetus, medical anthropologist Rayna Rapp articulates that, “communication failures between practitioners and patients are the result […] of differences in language, […] scientific literacy, […] and philosophy […] beliefs about the nature of disability; beliefs about the moral status of the fetus,” (Cowan). Rapp goes on to describe how non-directive counseling is more of a goal to strive for than a practice that is implemented, as the great array of human diversity makes it so no patient can truly be understood (Cowan). Rapp’s findings are confirmed in studies of prenatal counseling for families of children with Down Syndrome that show that this advising is anything but non-directive. (McCabe 708). In fact, in one case, a woman was blatantly lied to when she was told that the life expectancy for children with Down Syndrome is only 3 years. In actuality, the life expectancy of such a child is around 50 years today, and this example demonstrates a clear coercive effort to convince the mother to abort her child (McCabe 708). Furthermore, in the Netherlands, there is documentation that women were told that “their child would never be able to function independently” and that “the abnormality was too severe” 90%+ of the time (McCabe 709). Once again, these examples show clearly that in prenatal counseling, there often exists some coercive element in which physicians suggest that life would be better or easier if the fetus with Down Syndrome were to be aborted.

This coercion is perpetuated by some governmental institutions as well. “The California prenatal screening program described such [Down Syndrome] pregnancies that are continued as “‘missed opportunities,’” (McCabe 709). Furthermore, the official March 2009 California brochure given to women who have fetuses that have tested positive for Down Syndrome contained misinformation on the intellectual abilities of those with Down Syndrome. It stated that, “Infants with this birth defect are moderately retarded, a few are mildly or severely retarded,” (McCabe 709). In reality, recent studies have found that 34% to 39% of such individuals are in the mild range (McCabe 709). Ultimately, there exists some belief that those with Down Syndrome can not live full lives and that one should undergo amniotic testing for Down Syndrome and take action if the results are positive.

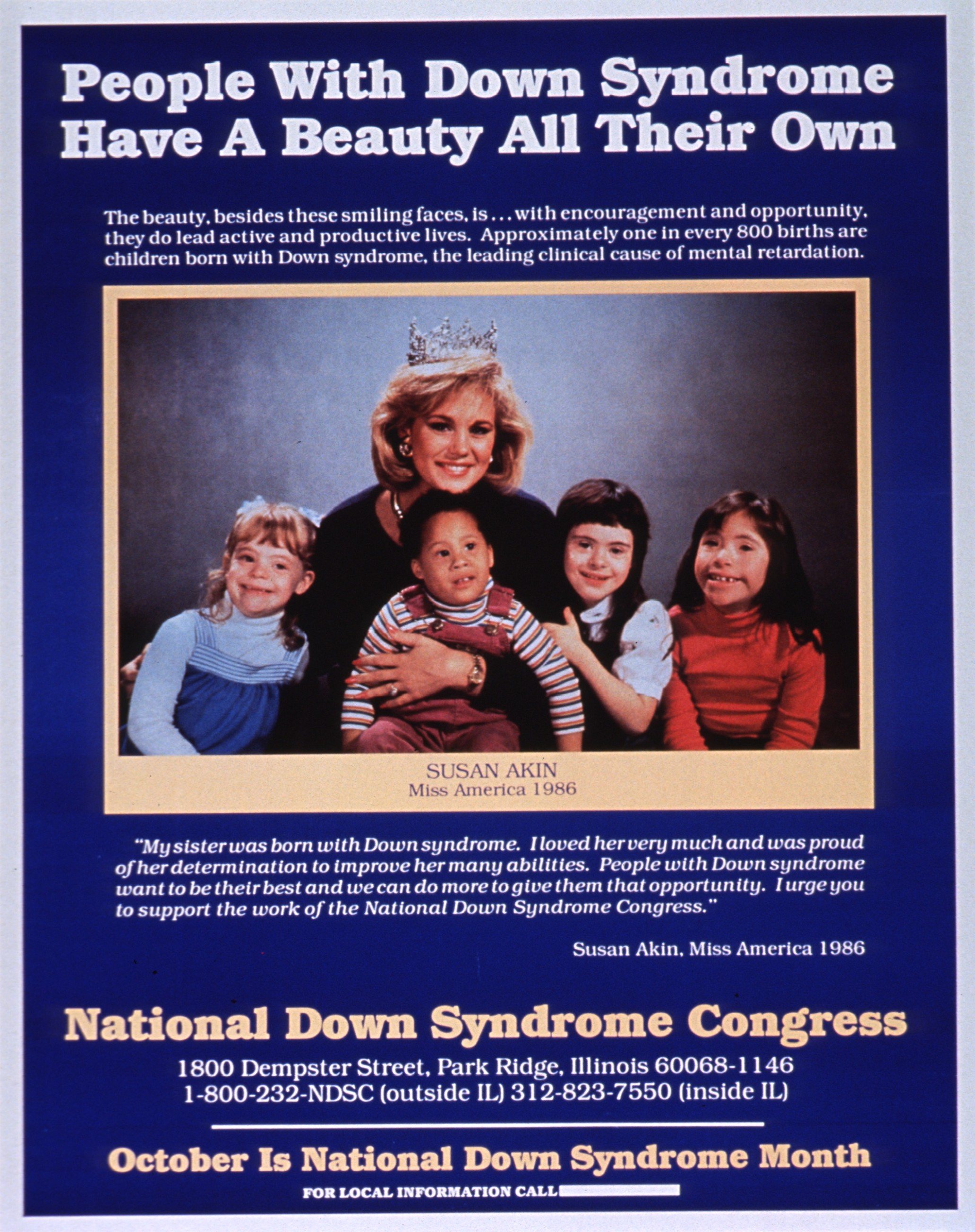

On the other hand, many believe that those with Down Syndrome can live full lives. These individuals believe that given the right opportunities, individuals with Down Syndrome can develop skills and function in society. In a 2001 study, Priscilla Alderson interviewed 40 people with congenital conditions and 5 individuals with Down Syndrome. The results of her study showed that these individuals attributed their lack of opportunities to social stigma rather than their condition (Alderson 635). Furthermore, the interviews showed that with the aid of their family and friends, the subjects with Down Syndrome were able to integrate themselves into mainstream society by attending mainstream schools and holding jobs (Alderson 627). In fact, one subject even held a job for a prenatal testing advisory agency (Alderson 634). The study demonstrated that Down Syndrome follows the social model of disability. That is, as Rapp describes, “that disability is not simply lodged in the body, but created by the social and material conditions that “dis-able” the full participation of those considered atypical,” (Rapp 53). Alderson’s study and separate research that has shown that 34%+ of individuals with Down Syndrome are only mildly cognitively disabled (McCabe 709) testify to the fact that people with Down Syndrome can live full lives. Down Syndrome advocacy organizations concur with this mindset, and a poster published by the National Down Syndrome Congress that expresses this viewpoint is posted below.

Figure 2: A Poster Published by The National Down Syndrome Congress that articulates that people with Down Syndrome can live full lives (“People With Down Syndrome”)

Alderson and McCabe’s research show that prenatal counseling can be overstated and that the coercive efforts to convince mothers of babies with Down Syndrome to terminate their pregnancies are efforts to take away full lives. Though Alderson states that more research must be done before statistics on the quality of life of those with Down Syndrome can be established, her interviews “show how some people with Down’s syndrome live creative, rewarding and fairly independent lives, and are not inevitably non-contributing dependents,” (Alderson).

Relation to Politics of Health

Down Syndrome relates to Politics of Health in the context of the concept of informed consent as described by Jill Fisher. Fisher examines recruitment strategies performed by pharmaceutical companies in their attempts to attract human subjects for clinical trials. In these attempts, pharmaceutical companies have diverted from the traditional ready-to-recruit model into a model of recruitment that resembles ready-to-consent (Fisher 195). In other words, pharmaceutical companies target individuals who do not have alternative mechanisms to make the money that they would through clinical research participation. Furthermore, in recruiting these populations, pharmaceutical companies often recruit individuals who do not have the knowledge to fully understand the research they are participating in or whose “understanding of […] medical research is rooted in [clinical trial advertising],” (Fisher 199). Therefore, those who are participating in this research and “consenting” to do so are not fully understanding what they are agreeing to do. Parallels to this lack of true informed consent occur with prenatal testing for Down Syndrome. As explained by McCabe, mothers whose fetuses have tested positive for Down Syndrome are often given targeted advice or coerced to abort these babies (McCabe 708). In prenatal counseling, these mothers are sometimes only told the negatives of having a child with Down Syndrome or given misinformation, as was done in the March 2009 California brochure for such women (McCabe 709). Therefore, as they are given such advice, they do not fully understand the decision they are making when they decide to abort their child, just as those participating in research do not fully understand what they are putting themselves through (McCabe 709). Neither situation represents true informed consent.

Down Syndrome also relates to Politics of Health through the concept of the social model of disability. As explained by Alderson, “ [the] social model [of disability] attributes [disability] mainly to disabling barriers and attitudes which unnecessarily exclude people from mainstream society,” (Alderson 628). Alderson’s research demonstrated that with the help of family and friends, some individuals with Down Syndrome were able to become productive and integrated members of society (Alderson 627). Thus, Down Syndrome viewed through the social model of disability would see the disorder as solely an impairment. In other words, having Down Syndrome in and of itself does not disable individuals from being active members of society. Instead, negative attitudes and social stigma regarding Down Syndrome serve to exclude these people from being functioning members of their community.

Works Cited

Alderson, Priscilla. “Down’s Syndrome: Cost, Quality and Value of Life.” Social Science &

Medicine, vol. 53, no. 5, 2001, pp. 627–638., doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00365-8.

“Amniocentesis.” American Pregnancy Association, 2 Sept. 2016,

americanpregnancy.org/prenatal-testing/amniocentesis/.

“AST Government Benefits.” National Down Syndrome Congress Center, National Down

Syndrome Congress, 2015, www.ndsccenter.org/wp-content/uploads/ASTgovt-benefits1.pdf.

Cooley, W. Carl, and John M. Graham. “Common Syndromes and Management Issues for

Primary Care Physicians.” Clinical Pediatrics, vol. 30, no. 4, 1991, pp. 233–253., doi:10.1177/000992289103000407

Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. “Testing Women, Testing the Fetus: The Social Impact of Amniocentesis

in America (Review).” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University Press, 11 June 2003, muse.jhu.edu/article/43530.

Dixon, Darrin P. “Informed Consent or Institutionalized Eugenics? How the Medical Profession

Encourages Abortion of Fetuses with Down Syndrome.” Issues in Law and Medicine, vol. 24, no. 1, ser. 2008, 2008, pp. 3–59. Hein Online.

“Down Syndrome Human and Civil Rights Timeline.” Global Down Syndrome Foundation, 20

Mar. 2015, www.globaldownsyndrome.org/about-down-syndrome/history-of-down-syndrome/down-syndrome-human-and-civil-rights-timeline/.

Fisher, Jill A. “‘Ready-to-Recruit’ or ‘Ready-to-Consent’€ Populations? Informed Consent and

the Limits of Subject Autonomy.” Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 13, no. 6, 2007, pp. 195–207., doi:10.1177/1077800407304460.

Gesell, Arnold, director. The Mental Growth of a Mongol. The Mental Growth of a Mongol, Yale

University, 3 Nov. 2011.

Koprowski, Kristen, director. Nondisjunction (Trisomy 21) – An Animated Tutorial. Arcadia

Genetic Counseling, 8 Dec. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=EA0qxhR2oOk.

Mccabe, Linda L., and Edward R. B. Mccabe. “Down Syndrome: Coercion and

Eugenics.”Genetics in Medicine, vol. 13, no. 8, 2011, pp. 708–710., doi:10.1097/gim.0b013e318216db64.

Megarbane, Andre, et al. “The 50th Anniversary of the Discovery of Trisomy 21: The Past,

Present, and Future of Research and Treatment of Down Syndrome.”Genetics in Medicine, vol. 11, no. 9, 2009, pp. 611–616., doi:10.1097/gim.0b013e3181b2e34c.

Penna, David, and Vickie D’Andrea-Penna. “Down Syndrome.” An Encyclopedia of American

Disability History, 2009, pp. 299–300.

“People With Down Syndrome Have A Beauty All Their Own.” U.S. National Library of

Medicine, National Down Syndrome Congress, 1986.

Rapp, Rayna, and Faye Ginsburg. “Disability Worlds.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 42,

- 1, 2013, pp. 53–68., doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155502.

“Three Types.” Down Syndrome Association of Central Ohio, dsaco.net/three-types/.

“What Causes Down Syndrome?” Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 31 Jan. 2017, www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/down/conditioninfo/causes.

“What Is Down Syndrome?” NDSS, National Down Syndrome Society, www.ndss.org/about-down-syndrome/down-syndrome/.

« Back to Glossary Index