Historical Context

In the 1860’s, American biologist, Francis Galton, brought the science of “hereditary improvement” in the realm of academia (Galton 1883). Influenced by Darwin’s Origin of Species, Galton researched the ways in which the human race is able to be manipulated through the selection desirable traits (Bulmer 2003). Like the way generations of cattle are bred to produce a high quality product, human eugenics held a practical importance to improve society (Galton 1883).

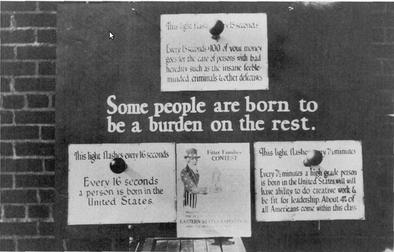

Eugenics Propaganda

In his book, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, Galton expresses his view of the most favorable trait to be one’s energy. In addition, criminals like thieves and murders breeding to create successors of the same is “one of the saddest disfigurements of modern civilization (Galton 1883).” Like body qualities, personality and mental traits were believed by Galton to be passed from parent to offspring, and thus could be controlled to create a refined future. Many famous statisticians were eugenicists, as well as other prominent historical figures, like Alexander Graham Bell, who warned against deafs breeding more deafs. Many prominent media producers also promoted eugenic thinking. Oftentimes, those with disabilities or conditions that were considered abnormal were not portrayed in movies, television shows, and books. This implicitly implies that those with disabilities do not add merit to media, and consequently that they do not have active roles in contributing to society (Davis 1995, 46). This value of ‘normal’ over disabled is inherently eugenic in nature, as it advocates for a uniform population free of undesirable traits.

Term Definition

A formal definition of eugenics was published in the American Journal of Sociology as field of science to “improve the inborn qualities of a race; also [to] develop them to the utmost advantage (Galton 1904).” The entry goes into detail of scaling the proportionality of positive and negative qualities to be “relative to the current form of civilization (Galton 1904).” By identifying the positive and negative traits in a society, eugenicists are able to breed for advantageous characteristics that benefit the individual and their respective community. It is important to recognize the influence that statistics has had on the development of eugenic thinking. There is a “real connection between figuring the statistical measure of humans and then hoping to improve humans so that deviations form the norm diminish” (Davis 1995, 30). The idea of statistics and the idea of eugenics both establish a societal norm, which consequently constructs ideas of normal, able bodies and abnormal, disabled bodies. In fact, Galton’s influence on changing the error curve to a normal distribution curve that used medians fostered a large surge in eugenic thinking about fitting in with the average man (Davis 1995).

Eugenics Background/Controversy

From 1910 to 1924, the United States Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, trained 258 women to collect data on inborn traits in places such as hospitals, mental asylums, and families of cognitively impaired persons, to analyze traits common throughout (Bix 1997). The director and prominent eugenicist of the time, Charles Davenport, supported this study as it was every Americans “duty to place on record a statement of physical, mental and moral qualities of their families (Bix 1997).” Yet, minority, low SES, and disables communities were the main populations being analyzed and noted for having negative traits. Over the course of the study, the field workers began to sympathize with the people being surveyed and voiced concern of unethical treatment (Bix 1997). Roughly 6 years after the legitimatization of eugenics, politicians and prominent figures began to fond the Eugenics Record Office program, but did not listen to the outrage brought on by their field workers against the unethical practices when executing orders from the program. Leading eugenicist and superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office (1910-1939), Harry H. Laughlin, composed a law that could be implemented at the state level called, “the Model Eugenical Sterilization Law,” of 1914. Social welfare institutions were the another main focus of eugenic programs in the early 20th century as these environments clustered those with traits undesirable. By 1922, “some 32,000 sterilizations had been performed in prisons, insane asylums, and homes for the epileptic or feebleminded (Lombardo 2010).” Laughlin’s Model Eegenical Sterilization Law, otherwise known as “Harry’s Model Law,” was passed in Virginia 10 years following its publication date (Lombardo 2010). In 1927, the Buck v. Bell case upheld Laughlin’s legislation as well-crafted and constitutional. The case followed a mother (Emma Buck), daughter (Carrie Buck), and granddaughter (Vivian Buck) as a prime examples in support of the compulsory sterilization of all “feebleminded” individuals as the trait must be hereditary and not due to environmental factors or by coincidence (Lombardo 2010).

In 1920, Emma Buck was sent the Colony (a psychiatric ward) after being diagnosed with pneumonia, rheumatism, and syphilis, as well as, receiving an IQ score of 50. These qualities led doctors to believe she “lacked moral sense… responsibility… [was] mentally deficient [and] a family moron (Lombardo 2010).” Carrie Buck was institutionalized in 1924 described to be of “the lowest grade moron class” due to being 18 years of age but having the mental capabilities of an 8 year old (Lombardo 2010). The Colony urged for the implementation of the sterilization law based off of Harry’s Model law because it seemed more demoralizing to keep her institutionalized until naturally becoming infertile in 30 or so years, a salpingectomy was performed without Carrie’s consent (Lombardo 2010). The 1927 United States Supreme Court ruled a Virginia law in favor of people, like the Buck family, to be surgically sterilized if declared “socially inadequate (Lombardo 2010).” Due to the outcome of the Supreme Court ruling on sterilization laws, over 64,000 mentally impaired and physically disabled where sterilized by state programs by 1960 (Lombardo 2010). Harry Laughlin, the creator of Harry’s Model Law, was an epileptic himself and considered a subject of sterilization, yet, as defined previously, Laughlin possessed education, whiteness, and other desirable attributes for his body to be viewed favorable in society (Wellerstein 2017). More recently, California prisons were exposed for forcing the sterilization of over 150 female inmates between the years 2006 and 2010. The state illegally paid physicians $150,000 to perform tubal ligations without consent. Like many southern states with African Americans, the eugenic sterilization in California was largely fueled by anti-Asian and Mexican prejudices, as many who were sterilized were of this decent. Ideally, these procedures would stop those of a less desirable race from reproducing and create a superior, eugenic society. While California is not the only state to have a history of eugenic sterilizations, it is one of the most recent and controversial. In 2015, the US Senate voted unanimously to pass the Eugenics Compensation Act, which gave compensation to surviving victims of forced sterilization and illustrated the growing condemnation of eugenic sterilization (“Unwanted Sterilization” 2017).

Modern Perspective/Controversy

By definition, the goal of eugenics must change to match the needs presented in society. This can be seen by the 21st century’s goal shift from filtering out undesirable populations in the human community to allowing the individual the right to choose genetic screening to guide future actions. Eugenics is prominent to this day as women are able to examine fetuses through prenatal screenings and terminate the pregnancy if appropriate. Rayna Rapp discusses in her book, “Testing Women, Testing the Fetus,” the aftereffects of receiving a prenatal test positive for some kind of mental disability, such as Down Syndrome, and the ethics in not aborting (Rapp 2000). If there is a high risk an unborn child may have a debilitating condition and the mother then chooses to terminate the pregnancy because of the abnormality, this is a case of “selective abortion (Rapp 2000).” Selective abortion, unlike selective breeding, is connected with less moral obligations as the disability cannot or will not be in the child’s best interest given the specific social context. Like selective breeding, selective abortions allow other, socially adequate, people to determine who is fit to live in the human community. The doctor, the researcher, and the mother force the unborn child into a “vacuum” where is it seen as disabled for its’ entire life before ever showing any difficulties adjusting to society (Rapp 2000). Inside the womb, the child has not met the “gatekeepers” standards for entry into the human community, thus becoming disposable like those made infertile years prior (Rapp 2000).

Rapp raises concerns in her book of the biases and stereotypes linked to disabled identities and the impact those have of modern-day eugenics. Sickle-cell anemia and cerebral palsy exist at higher rates in Blacks populations than that of Whites (Rapp 2000). She does not insist that a diagnose of such a disability in an African-American women would cause her to seek an abortion unlike a White woman, but rather the Black woman knows what is it like to live with a person with cerebral palsy because of this fact (Rapp 2000). This idea acknowledges other identities without othering persons whom are under-represented in society. To abort a fetus because it has been declared high risk for sickle-cell anemia implies an ideal future with no persons with sickle-cell anemia. The ethical question of “gatekeeper” in allowing which bodies to enter society are not questioned because it is seen as a negative trait in the eyes of most (Rapp 2000). As seen in the Bell v. Buck case, sterilization was seen as a “humanitarian and economic provision” because it lessened the births of children with mental disabilities (Lombardo 2010). In this example, gatekeeper was the state and social workers, nevertheless, individuals (like pregnant women) can determine which bodies are normal enough for society. The overall goal for eugenicists is to produce societal members that will contribute to something greater than themselves and be self-sustaining. However, this mentality of bettering the fetus for the hardships of life follows the mindset of eugenic thinking of the 1900s.

Summary

The connection between politics of health and eugenics is most clear when considering the class concept of normalcy. The goal of eugenics is to create a race free of flaws and deviations from the norm. In regards to health, deviations from the norm would be disabilities. The idea of using eugenics to create a uniform, normal population frames every difference as a problem (Davis 1995). When considering healthcare, those who aren’t seen as normal and as minorities often have limited access to subpar care. This can extend to any group that is marginalized, from people of color, to women, to those with chronic disabilities. This access gap propagates a circle of inequity, as without care, many conditions are exacerbated and seen by society as more and more abnormal. From a eugenic point of view, those who are marginalized should be bred out of society, promoting a uniform population that does not have an access gap to healthcare, as there are no differences in individuals. As mentioned earlier, the definition of eugenics allows the study to transform as the needs of the society are altered. Former eugenic practices of the 20th century were dominated by the nonconsensual sterilization of socially inferior communities, yet people performing these surgeries did not view the practices as immoral because the end benefits outweighed current rejection. Today, the argument of selective abortion is whether or not it is moral for a fetus classified as high risk for severe physical or mental impairments to be granted entrance into the human community. In another 50 years, eugenics in the United States will viewed differently than now as the practice of selective abortion may become obsolete and another practice arises.

Citations

Bix, Amy Sue. “Experiences and Voices of Eugenics Field-Workers: ‘Women’s Work’ in Biology.” Social Studies of Science 27, no. 4 (1997): 625-68

Bulmer, M. G. “Francis Galton : Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry.” Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Davis, Lennard. 1995. Constructing Normalcy. In Enforcing Normalcy. Pages 123 – 149.

Galton, Francis. “Inquiries Into Human Faculty and Its Development.” Macmillan, 1883.

Galton, Francis. “Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims.” American Journal of Sociology, (1904), 10:1, 1-25. Lombardo, Paul A. 2010. Three Generations, No Imbeciles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press.

Rapp, Rayna. 2000. Testing Women, Testing the Fetus : The Social Impact of Amniocentesis in America. New York: Routledge, 2000.

“Unwanted Sterilization and Eugenics Programs in the United States.” PBS. Accessed April 02, 2017. http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/unwanted-sterilization-and-eugenics-programs-in-the-united-states/.

Wellerstein, Alex. 2017. “Harry Laughlin’s Model Law.” Harry Laughlin’s Model Law.

« Back to Glossary Index