For-Profit Hospitals

Phoebe White

Would you trust a doctor driven by profit with your baby’s life? A 2017 meta-analysis, including 17 individual studies accounting for 4.1 million women, of caesarean sections (more commonly, C-sections) was performed to compare the percentages of this procedure in for-profit hospitals and nonprofit hospitals. Caesarean sections are more expensive than natural birth (In the United States) and are less time consuming for the doctors and nurse personal: a business person’s dream. The study found that women are 1.4 times more likely to be given a caesarean section in for-profit hospitals compared to nonprofit hospitals. This held true even in high risk pregnancies. This begs the question: Is the for-profit hospital’s motive patient care or profit? (Hoxha)

Background & Historical Context

Health and Commercialism

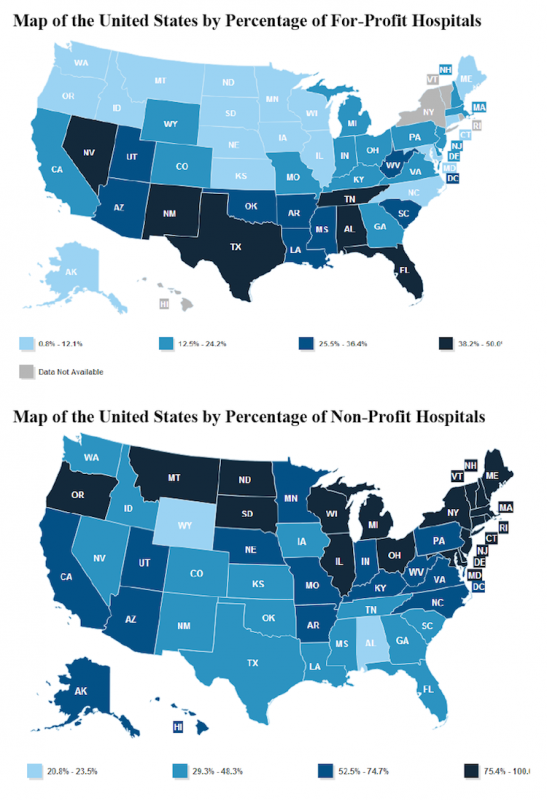

A for-profit hospital, also known as an investor-owned hospital, is a privately-owned business that profits from patient care. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the leading nonprofit for American Economic research holding twenty seven noble prizes, the for-profit hospital differs from the traditional nonprofit hospital and the state-owned hospital in many ways including: they are corporate-owned and ran, owners profit any surplus the hospital makes, the surplus is comparatively higher, they have to pay taxes, and the mission of the hospital, along with patient care, is to turn a profit. They turn a larger profit while getting less aid from the state. To do this, for-profit hospitals use more cost-efficient supplies and charging the public more. These two changes are difficult for nonprofits because they need government approval and there is no direct motivation for change as they are not motivated by profit. (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2000). Today, most for-profit hospitals are actually “hospital systems”, large groups of hospitals that are run by one corporation. Notable systems include Hospital Corporation of America (173 hospitals), Community Health Systems (154 hospitals) and LifePoint Health (64 hospitals), all of them based in Tennessee (Gooch, 2017). One reason that they may all be located in Tennessee, is that the state has historically low taxes. According to Semuels, the state has “the most regressive tax system in America” (Semuels, 2015, paragraph 2), which means incredibly profitable corporations, such as For-profit hospitals, would thrive in this sate. In the US today, there are 1,035 for-profit hospitals, which translates to about 19% of all hospitals (AHA, 2018). As seen in the figure below (fig. 1), the prevalence of the For-profit hospital versus the prevalence of the nonprofit hospital varies heavily by state.

Figure 1: Percentage for-profit versus percentage nonprofit by state in the US. (Harley)

The reform of the classical hospital caused many changes to the code of ethics, a set of guidelines set out for all healthcare providers to follow, set by the American Medical Association (AMA), the largest group of medical professionals and medical students in the US whose goals includes advancement of scientific research and creating better public health (AMA website). In 1969, before the influence of for-profit hospitals began, the AMA stated “the practice of medicine should not be commercialized nor treated as a commodity in trade” (AMA quoted by Relman, 2004, page 302). The current opinion of the AMA has changed to “although one of the primary duties any corporation holds is to its shareholders, an organization providing or funding health care must also realize how its decisions can affect the health and livelihood of individual patients” (AMA, 2009, page 4). This recognition of the role of commercialism in the health care system is fundamental to understanding the new ‘norm’ of for-profit hospitals.

Why the 1960s?

It was not until the 1960’s that for-profit hospital became common place in the United States (Relman, 2004). Medicare and Medicaid were introduced in 1965, which increased the access of many Americans to healthcare. It also gave almost every American senior citizen a guarantee to hospital admittance and access to a physician. This created a huge influx in patients as before many retired elderly people could not afford such a visit. (Rowland, 1996). In 2015, 46 million elderly people have Part A Medicare which is sector that covers hospital insurance (NCPSSM, 2015). As long as Medicaid prices stay low, the young and adult underinsured will also continue supplying the For-profit hospital with patients and revenue. There was also an increase in employers providing health care packages during this period. These two factors lead to a lack of suppliers for these new health care needs. This gap in the market was filled by the for-profit hospital (Catlin, 2015).

Managed Care Insurance

The next big change that increased the presence of for-profit hospitals came in 1994 when the Clinton health reform bill failed (Relman, 2004). The bill was a universal health care bill that aimed to provide an overall better system for Americans to manage their health. The bill ultimately failed due to conservative Republicans arguments of too much government regulation. (Zelman, 1994). The failure lead to many Americans without health care, this created another, much different, gap in the market. Insurance providers matched with for-profit hospitals to provide those in need with managed care packets (Relman, 2004). Managed care insurance is when an insurance provider has a network of healthcare providers that it allows their costumers to solely use. These packages are lower cost for all parties, and higher profit for the for-profit hospital and insurance provider (Medline, 2016). This allowed for the growth of the for-profit hospital.

Controversy

The main issues

Should profit drive those who are responsible for human lives? This is where the largest controversy lies when considering for-profit hospitals. Relman considers the “degree to which business values should control the healthcare system” (2004, page 301).

Supporters of the for-profit hospital main argument is that it fuels medical innovation and improvement. If a hospital’s goal is profit, they will do everything in their power to provide the best product, and that product is human health. This is the fundamental idea behind the free market and economic competition, but healthcare works under different circumstances. Relman explores these flaws, “consumers (patients) can make relatively few independent and informed purchasing decisions because they must rely so heavily on advice from their physicians” (2004, page 303). A purchase gets complicated when the seller is the only one who holds the information about what is best and the decision is life or death. It is therefore a fundamentally unfair market, which leads to the other opinion on the controversy: health should not be commercialized. Many believe that hospitals focus should be solely on patient care. People and healthcare workers largely think “medical care to be a social good, not an economic commodity” (Relman, 2004, page 303). What is to stop physicians and hospitals to make a decision that benefit them financially, rather than benefit the patient’s care. This is clearly shown in the aforementioned caesarean section example. Another concern of the For-profit hospital is that doctors order expensive, unnecessary medical procedures and medicines (Hart, 2009). This is crucial to the opposition as most Americans place a lot of trust in the “white coat” and do not have the medical knowledge to make informed decisions, costing those peoples huge amount of money unknowingly

Open Heart Surgery

It is imperative to consider the outcomes of for-profit hospitals, compared to those of the nonprofit hospitals. The largest tangible effects of the for-profit hospitals are that they are more likely to perform high-profit or media seeking procedures then their nonprofit counterparts. A 2005 study showed that for-profit hospitals are just over seven percent more likely to preform open-heart surgery then nonprofit hospitals, a procedure that is both showy and profitable (Horwitz, 2005). According to the National Heart, Lung and Blood institute, one of the National Institutes of Health, the risks of open heart surgery include infection, stroke, permanent tissue damage and death (NHLBI, 2018). Such a discrepancy in the willingness to perform a highly risky procedure is concerning if there is a profit motive to say ‘yes’.

What else?

There are many more contentions on the subject matter. Kushnick discusses the issues in “the gaps in current legislation that fail to prevent for-profit hospitals from engaging in predatory billing and bill-collection practices” (2015, paragraph 6). Other studies show that “Nonprofits appear to be falling short of providing the expected level of community benefits” and for-profits may be the answer (Nicholson, 2000, page 1). The controversy considers economics, patient health, doctors, community benefit and government involvement.

It is clear that the practice of medicine is no longer about simply healing the ill, but rather another entity the capital market has turned into a competitive market. Physicians have to abide by the Hippocratic oath along with the rules of supply and demand. Whether or not this aids patient care and medical advancement is still, and will most likely always be, a controversial debate. What can be stated as fact is that medical expenses are rising to, for many, unbearable rates. President Obama stated in a 2009 speech, “The greatest threat to America’s fiscal health is not Social Security…By a wide margin, the biggest threat to our nation’s balance sheet is the skyrocketing cost of health care. It’s not even close.” (Barack Obama quoted by Gawande, 2015, paragraph 3). His presidency resulted in the Affordable Health Care Act, nicknamed “Obamacare”, which was a universal health care bill for all US citizens in an attempt to make healthcare more affordable and accessible (KFF, 2013). This Act was repealed under President Trump’s administration which has huge implications for the health care sector. According to NBC news, the Trump presidency has largely worsened the increasing price of health care, predicting that by next year 6.4 million people will be uninsured. (NBC news, Sarlin 2008). This will have huge negative effects on the profit margins of the For-profit hospital, simply because less people will be able to use their services. Since these hospitals stand somewhere in the middle of the free market and government control, the political decisions have huge consequences on their profitability.

Politics of Health

The topic of for-profit hospitals relates to politics of health through two concepts: medicalization and pharmaceuticalization. Medicalization takes nonmedical entities and gives them a name and a treatment. The three driving forces od medicalization is biotechnology, patients as consumers and managed care. (Conrad, 2005). Since for-profit hospitals are at least partially driven by profit, they thrive off medicalization. All three of the engines of medicalization are also what drives For-profit hospitals: 1) biotechnology is one of the kinds of technological advancements that many argue is the benefit of making medicine competitive, 2) patients as consumers are the very ground of For-profits, as if they did not have these consumers they would not make a profit and 3) as mentioned before, managed care insurance, allows for consumers to only be able to visit one circuit of For-profit hospitals which highly increases their profitability. More unhealthy people means more hospital visits and more profit. This also connects to pharmaceuticalization through the lens of commercialization. The commercialization of drugs is a new concept that is driven by profit and medicalization (Williams, 2015). There are more diseases, so more drugs need to be created and more hospitals to administer these drugs. The whole trend in health is towards becoming commercial, as represented in the cartoon below (fig. 2) profit becomes more important than a cure. The world has blurred the line between health and sickness, to turn a profit. Health is no longer just the absence of disease but rather “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” by definition of the World Health Organization (WHO quoted by Huber, 2011, page 1). A person can, therefore, only be truly healthy if all possible outlets of imperfections are consulted by a physician. A physician that works in a for-profit hospital, that is.

Figure 2: Hospital profit motive cartoon. “While we can’t cure you, we can turn your disease into a long-term profitable condition…”

‘While we can’t cure you, we can turn your disease into a long-term profitable condition…’

Additional Recourses:

“SummaryMedicareMedicaid.” CMS.gov Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 21 Nov. 2017, www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/SummaryMedicareMedicaid.html.

The entry discusses the implications of Medicare/Medicaid for for-profit hospitals. The programs start was pivotal in the creation of the for-profit hospital, as well as in its continuation. This resource gives a history of the government insurance policy as well as how it is used today. It discusses who is ensured, what they are insured for and the programs’ finances. It also includes a section on the financial future, which is important for the future discussion of for-profit hospitals.

Writer, Author Bill Fay Staff. “Hospital and Surgery Costs – Paying for Medical Treatment.” Debt.org, www.debt.org/medical/hospital-surgery-costs/.

This article discusses the extreme costs of having a hospital stay. Also, the piece explains how much a medical procedure can vary between hospitals or even within hospitals. This demonstrates how profitable a hospital can really be as well as how varied. For-profit hospitals may be able to manipulate this unregulated territory to their advantage, another take on the disparity for-profit hospitals can create.

Barbetta, Gian Paolo, et al. “Behavioral Differences between Public and Private Not‐for‐Profit Hospitals in the Italian National Health Service.” Health Economics, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 23 Aug. 2006, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hec.1143/abstract.

I chose this article to contrast the American medical system. The piece discussed for-profit hospitals in Italy. It is interesting to explore the implication and beginnings of the for-profit hospital in a different realm than Medicare/Medicaid. Do the same conclusions hold true for a European country as they do in America?

Bibliography

American Medical Association | AMA, 2018, www.ama-assn.org/.

Sarlin, Benjy. “Studies Find Trump Health Care Will Drive up Premiums.” NBCNews.com, NBC Universal News Group, 28 Feb. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/politics/white-house/studies-find-trump-health-care-will-drive-premiums-n852086.

Catlin, Aaron. History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 . Nov. 2015, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/HistoricalNHEPaper.pdf

“Code of Medical Ethics: Financing and Delivery of Health Care.” American Medical Association, 2009, www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/code-medical-ethics-financing-and-delivery-health-care.

Conrad, Peter. “The Shifting Engines of Medicalization.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, vol. 46, no. 1, 2005, pp. 3–14., doi:10.1177/002214650504600102.

“Fast Facts on US Hospitals.” AHA Hospital Statistics, Feb. 2018. https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-02/2018-aha-hospital-fast-facts_0.pdf

Gawande, Atul. “The Cost Conundrum .” The New Yorker, 1 June 2009, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/06/01/the-cost-conundrum.

Gooch , Kelly. “13 Largest For-Profit Hospital Operators.” Becker’s Hospital Review, 2018, www.beckershospitalreview.com/lists/13-largest-for-profit-hospital-operators.html. \

Horwitz, J. R. “Making Profits And Providing Care: Comparing Nonprofit, For-Profit, And Government Hospitals.” Health Affairs, vol. 24, no. 3, 2005, pp. 790–801., doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.790.

“Heart Surgery.” National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018, www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/heart-surgery.

Hoxha, Ilir, et al. “Caesarean Sections and for-Profit Status of Hospitals: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ Open, vol. 7, no. 2, 2017, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013670

Huber, Machteld. “How Should We Define Health?” BMJ , 2011, pp. 1–3., doi:10.1136/bmj.d4163.

Kushnick, Hannah. “Medicine and the Market.” AMA Journal of Ethics, vol. 17, no. 8, Aug. 2015, pp. 727–728., doi:http://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/2015/08/fred1-1508.html.

“Managed Care: MedlinePlus.” MedlinePlus Trusted Health Information for You, medlineplus.gov/managedcare.html.

Murphay, Chris, “Map of the United States by percentage of For-Profit Hospitals” , murphy.senate.gov, https://www.murphy.senate.gov/download/the-impact-of-for-profit-medicine-on-medicare

Ncpssm. “Medicare .” NCPSSM, www.ncpssm.org/.

Nicholson, S., et al. “Measuring Community Benefits Provided by for-Profit and Nonprofit Hospitals.” Health Affairs, vol. 19, no. 6, 2000, pp. 168–177., doi:10.1377/hlthaff.19.6.168.

Relman, Arnold S. “Profit and Commercialism.” Gale Virtual Reference Library, vol. 4, no. 3, 2004, pp. 2169–2172., http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=nash87800&id=GALE%7CCX3402500442&v=2.1&it=r&sid=GVRL&asid=c60560a3

Rowland, Diane, and Barbara Lyons. “Medicare, Medicaid, and the Elderly Poor.” NCBI , 1996, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4193634/.

National Bureau of Economic Research. The Changing Hospital Industry Comparing Not-for-Profit and for-Profit Institutions. University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Schwadron, Harley, “While we can’t cure you, we can turn your disease into a long-term profitable condition…”, cartoonstock.com, hsc3050, www.cartoonstock.com/directory/p/profitable.asp

Semuels, Alana. “Congratulations Tennessee: You’ve Got the Most Regressive Tax System in America.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 21 Oct. 2015, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/10/tennessee-tax-system-regressive/411547/.

“Summary of the Affordable Care Act.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 23 April 2013, www.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/summary-of-the-affordable-care-act/.

Williams, Simon J., et al. “The Pharmaceuticalisation of Society? A Framework for Analysis.” Sociology of Health & Illness, vol. 33, no. 5, 2011, pp. 710–725., doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01320.x.

Zelman, W. A. “The Rationale behind the Clinton Health Care Reform Plan.” Health Affairs, vol. 13, no. 1, 1994, pp. 9–29., doi:10.1377/hlthaff.13.1.9.

« Back to Glossary Index