Forced Sterilization

by Emily Reed

Forced sterilization, sometimes referred to as compulsory sterilization, or coerced sterilization, is defined as “any procedure that renders a legally incompetent person permanently infertile” (Involuntary sterilization, 2009, para. 1). There are many controversial aspects associated with this definition, for example, how do our legal systems determine an individual to be incompetent? What are the implications of sterilizing an individual because he/she is deemed “lesser” in society? Forced sterilization in the United States is therefore an issue rooted in a deep and politically controversial past. What was made public knowledge of forced sterilization in the United States is often examined in the broader context of the eugenics movement (Largent, 2008). The eugenics movement is therefore not only the epidemiology of forced sterilization, but also served as its justification.

Sir Francis Galton largely developed eugenics ideology in the late nineteenth century. Eugenics is the belief that the gene pool of our species may be enhanced by preventing socially or intellectually challenged individuals from reproducing (Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, 2009). The eugenics movement therefore stemmed from, and was justified by, biological sciences, as proponents such as Galton believed that, “just as the quality of the species can be improved in animal and plant species by selective breeding, it was thought by some that similar principles could be applied to maintain [or enhance] the quality of the human species” (Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, 2009, p. 484). Therefore, nations such as the United States used eugenics practices following the belief that: if weaker members of society could not reproduce, then the nation and its people would become more powerful. After Galton illuminated the supposed benefits of eugenics, forced sterilization eugenics projects were born in the United States to begin the process of genetic purification of the American population (Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, 2009). In the early 1900s, two men, Charles Davenport, and Harry Laughlin, took control of the movement in the United States (Largent, 2008).

Davenport, a respected scientist of his time, claimed that American degeneracy was a result of genetic inheritance. During his time, the Eugenics Record Office, or the ERO, was formed and led the American eugenics movement (Largent, 2008). Through his research, Davenport published a book in 1911 called Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, which provided “intellectual legitimacy [for] efforts to protect the human gene pool” (Reilly, 2015, para. 17). Because Davenport was well respected as a scientist and was able to produce literature that made his research appear legitimate, the forced sterilization movement was progressed. Davenport’s colleague, Laughlin, believed that “by sterilizing “social[ly] inadequate citizens,” authorities could solve any number of complicated social problems” (Largent, 2008, p. 3). As a result of these ideas and those who supported the eugenics movement, “thirty states in the US passed eugenics laws between 1907 and 1931, and these laws were upheld by the US Supreme Court in 1916 and 1927” (Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, 2009, p. 485). As a result, by the early 1960s, it is estimated that “more than 63,000 Americans were coercively sterilized under the authority of these laws” (Largent, 2008, p. 7). As they were coercively sterilized, it was often the case that at the time of sterilization, the individuals did not fully understand the implications of the surgery. These young women, and sometimes young men, were left unable to have children who could continue the legacy of their family name.

Early forced sterilizations had far reaching consequences, as the sterilization movement was not isolated to America. The ideas of Laughlin and Davenport set a precedent as they “helped shape the content of the “racial hygiene” law enacted by the Nazi party in 1934” (Reilly, 2015, para. 21). Nazi Germany provides a clear example of the global implications that forced sterilization practices in the United States had in a broader context. For the same reasons the United States enacted eugenics programs, to supposedly enhance the gene pool, Nazi Germany utilized similar horrific techniques to promote the Aryan race, one that Hitler deemed “superior” to all other races (The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, n.d., para. 13). The devastating results of “racial hygiene,” stemming from forced sterilization practices in the United States, took the lives of many innocent men and women across seas during World War II. As news of Nazi practices made its way back to America, due to the Nuremburg trials of 1945 (Reilly, 2015), forced sterilization was reconsidered in many states. Some Americans were ashamed of the impact their practices had on innocent lives abroad.

Hearing of the atrocities of war, many of the sterilization programs ended. By 1950, a reported 1,526 persons were sterilized by various institutions in the United States. While this number still seems high, it was a significant reduction from the 2,500 operations that took place a decade earlier in 1939 (Reilly, 2015). However, while there were many fewer active sterilization programs, all were not completely eradicated. “The overall decline in state-enabled sterilizations would have been even more dramatic [in the US after WWII] but for new activity in a few Southern and Midwestern states,” when a not-for-profit organization called “Birthright” was born (Reilly, 2015, para. 38). The Birthright organization was led by Dr. Clarence Gamble. This program was characterized as a movement to sterilize poor rural women, who were often under the age of 20. Specifically, the Birthright program flourished in the state of North Carolina, which later became known as one of the last U.S. States to practice forced sterilization (Reilly, 2015).

North Carolina is significant with respect to forced sterilization, because after World War II when most US states began to cut back its sterilization activities, North Carolina enhanced theirs. In the documentary, Wicked Silence, John Railey, journalist for the Winston-Salem Journal, recounts the history of coerced sterilization in North Carolina through the stories of three victims (Wicked Silence). It was discovered through Railey’s research, that “between 1929 and 1974, North Carolina sterilized more than 7,500 residents for being “feebleminded” and unfit to reproduce” (Jones, 2017, para. 1). The majority of these compulsory sterilizations occurred between 1946 and 1968, with a significantly lower number of only 48 people being sterilized after 1971 (Jones, 2017). However, this was still approximately twenty years longer than most other states. Elaine Riddick, an African-American woman who, at a young age, became a victim of forced sterilization in North Carolina, is currently one of the main advocates for other victims such as herself (Jones, 2017). Throughout Wicked Silence, Riddick tells Railey her story. Elaine was raped and got pregnant. She then birthed her only child at the age of fourteen. As a result, the Eugenics Board, which had the power to deem an individual “feebleminded,” or in Elaine’s case, “promiscuous,” decided Elaine should be sterilized (Wicked Silence). The Eugenics Board obtained “formal permission” at the time from Elaine’s illiterate grandmother, who signed the consent form with an “X” (Jones, 2017). The doctors did not fully explain the procedure to Elaine, but she later discovered that they had tied, clipped, and burned her fallopian tubes to ensure she would not have any more children (Wicked Silence). Research of these compulsory sterilization incidents found that “77% of all those sterilized in North Carolina were women” and that “about 2,000 [of these] people were 18 and younger,” (Vasquez, 2017, para. 5), an age hardly old enough to decide if one would want children in the future.

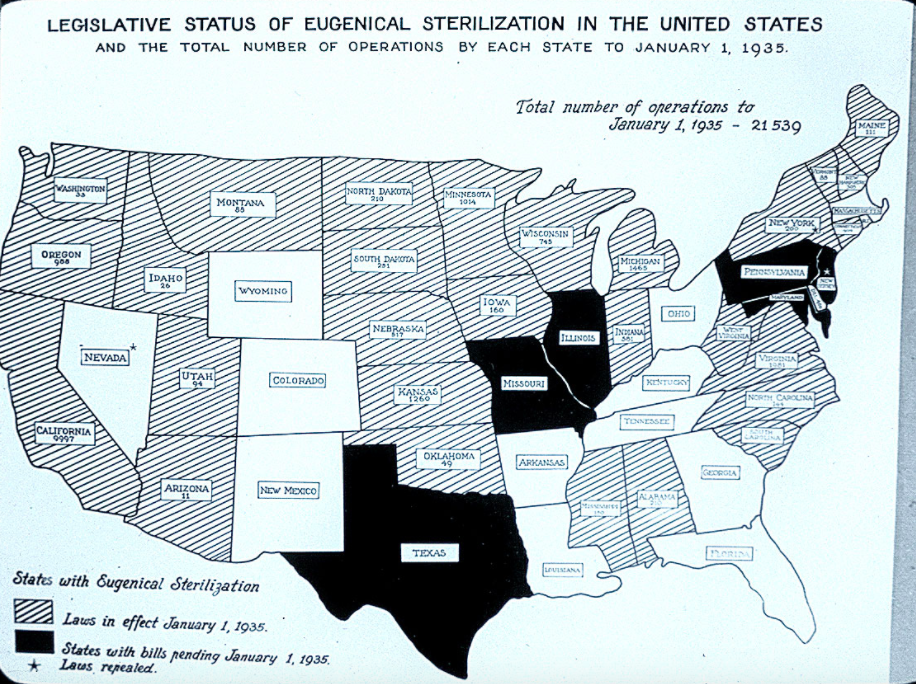

Map of the United States in 1935. The majority of the 50 states already had eugenics sterilization laws in effect, and several others were pending sterilization legislation that would take effect on January 1st, 1935. This image states as of January 1st, 1935, there were a total of 21,539 eugenics sterilization operations in the United States. States with no legislation in effect or pending, are clearly seen in the minority (Ko, 2016).

Given the racial discrimination characteristic of our nation’s history, one might expect that it was young African American men and women who were the main victims of sterilization in the United Stated. However, poor, rural, white young women were primarily the targets of the eugenicists’ operating tables (Vasquez, 2017). Health-care historian Rebecca Kluchin provides an intriguing explanation for this chosen population of victims, which is that segregation actually “shielded some black women from the eugenicist’s scalpel… because they were excluded from white health-care institutions” (Vasquez, 2017). As most of these sterilizations happened within the walls of a hospital after a parent or legal guardian signed off on the surgery, it was unlikely that African American men or women would be victims, considering they could not enter white hospitals for even routine check-ups. However, this protection did not last indefinitely, as after Jim Crow, the black population inhabiting North Carolina became eligible for public health assistance, at which point they too became a target population of forced sterilization (Vasquez, 2017).

In the 1970s, a brave victim, Nial Cox Ramirez, with the help of Glori Steinem and attorney Branda Feigen filed a lawsuit “as part of the early work of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Reproductive Freedom Project” (Vasquez, 2017, para. 7). Many historians today credit Ramirez and her lawyers with the successful termination of North Carolina’s eugenics programs. While the initial sterilization law was repealed in 1974, it took approximately 30 more years until the governor of North Carolina issued a formal apology to the victims in 2002. After the formal apology was given, victims were also offered financial compensation (Reilly, 2015). Ultimately, $10 Million was awarded to those who were forcibly sterilized, which some victims still argue is hardly enough for the pain that the sterilization projects brought them (Vasquez, 2017). While advocates of eugenics through coerced sterilization believe the efforts of the Eugenics Board were a positive attempt to purify the genetic pool of American society, through the stories of its victims, one can clearly understand the life-long detrimental effects these procedures had on individuals’ mental health and future lives.

One may be tempted to believe these horror stories were merely practices of the past. However, “sterilization stories are still emerging” (Vasquez, 2017, para. 14). This term is related to the politics of health because, ideas like eugenics are built upon societal belief systems in which people are separated by those which society values, and those which our society does not. “It’s this belief that people of value know better for other people’s lives” (Vasquez, 2017, para. 16), that perpetuates movements such as forced sterilization.

For example, today, “prisoners at the White Country jail in Sparta, TN, have recently been given a horrifying choice: serve their entire sentence behind bars, or agree to undergo sterilization, courtesy of the Tennessee Department of Health, in exchange for a reduced sentence” (Schwartz, 2017, para. 1). Local judge Sam Benningfield approved this new program as of May 2017 (Schwartz, 2017). This “choice” relates back to Fischer’s idea of “ready-to-consent,” in a different way. A “ready-to-consent” population, as defined by Fischer, is a population that does “not have better alternatives than participation in clinical trials” (Fischer, 2007, para. 1). While sterilization is not a clinical trial, as we know the effect of the procedure is irreversible, inmates at the White Country jail, have no better alternative than to accept the sterilization. These individuals therefore, are being coerced to undergo a procedure with a clear incentive, despite the negative life-long consequences. “As of May 15, [already] more than 30 women have had Nexplanon – a small rod that can prevent pregnancies for up to 4 years – implanted in their arms free of cost, in exchange for 30 fewer days in jail…and 38 men also agreed to undergo a vasectomy surgery for the same program” (Schwartz, 2017, para. 3). Judge Benningfield in support of his program stated, “I hope to encourage [prisoners] to take personal responsibility and give them a chance, when they do get out, to not to be burdened with children” (Schwartz, 2017, para. 4). However, advocates against the program spoke out as well. Georgia State law professor and historian, Paul Lombardo stated, “The history of sterilization in this country is that it is applied to the most despised people—criminals and the people we’re most afraid of, the mentally ill—and the one thing that these two groups usually share is that they are the most poor… That is what we’ve done in the past, and that’s a good reason not to do it now” (Schwartz, 2017, para 10). While there are differing opinions on the matter, the door for forced sterilization is certainly still open in modern-day American society, and is a topic on which we should approach cautiously, so that we do not repeat our nation’s past.

A topic contemporary topic with which the United States may want to approach with extreme caution is the current debate about genetic screenings during pregnancies. On July 26, 2017, a major breakthrough in human gene editing was released. Scientists were able to successfully edit out a gene in an embryo that would cause heart disease in the child (Cokley, 2017). While many may view this as incredible progress in ensuring prevention of disease among our children, others who are members of the disabled community, view this as terrifying to their populations. Rebecca Cokley, an individual who has classic dwarfism, argues that persons with disabilities, “have traditions, common language and histories rich in charismatic ancestors” (Cokley, 2017, para. 7), and that if society is able to edit out the gene for these disabilities and to eliminate certain populations from the human species, it is an act similar to eugenics projects. Gene editing may be evidence then that the eugenics theories that fueled the forced sterilization movement have not been eradicated from American society and are in fact still at play in contemporary debates. Anthropologists Karen-Sue Taussig, Rayna Rapp, and Deborah Heath note in their piece Flexible Eugenics, that society is currently at a point in which “we are all rapidly being interpolated into the world of genetic discourse, where resonances, clashes, and negotiations among interested parties occur at increasing velocity” (Taussig et al, 2005, p. 72). While the authors acknowledge that the history of eugenics gives reason to approach this period in history with caution, that “an ethnographic perspective on the openness of these encounters and practices may give some cause for optimism of the will” (Taussig et al, 2005, p. 73). In other words, if we approach the issue with caution, keeping in mind historical atrocities such as sterilization projects, genetic editing may be used for positive purposes at the will of the individual. However, there remains a fine line between medical advancements and eugenics as it pertains to the particular issue of gene editing, therefore, there is no “correct” side to take in this current debate.

Works Cited

Cokley, R. (2017, August 10). Please don’t edit me out. Retrieved October 15, 2017, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/if-we-start-editing-genes-people-like-me-might-not-exist/2017/08/10/e9adf206-7d27-11e7-a669-b400c5c7e1cc_story.html?utm_term=.7656e36bc8f5

Encyclopedia of Race and Racism. (2009). J.H. Moore (Ed.), Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. Retrieved September 19, 2017 from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=nash87800&v=2.1&it=aboutBook&id=GALE%7C9780028661162

Fisher, J. A. (2007). “Ready-to-Recruit” or “Ready-to-Consent” Populations?: Informed Consent and the Limits of Subject Autonomy. Qualitative Inquiry : QI, 13(6), 875–894. Retrieved September 20, 2017, from http://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407304460

Involuntary sterilization. (2009) Medical Dictionary. Retrieved September 24 2017 from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/involuntary+sterilization

Jones, M. (2017, June 27). Photos: Survivors of North Carolina’s Eugenics Program. Retrieved September 24, 2017, from http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012/05/north-carolina-sterilization-eugenics-photos/

Ko, L. (2016, January 29). Unwanted Sterilization and Eugenics Programs in the United States. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/unwanted-sterilization-and-eugenics-programs-in-the-united-states/

Largent, M. (2008). Breeding Contempt: The History of Coerced Sterilization in the United States. NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY; LONDON: Rutgers University Press. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhz9f

Reilly, P. R. (2015). Eugenics and involuntary sterilization: 1907–2015. Annual review of genomics and human genetics, 16, 351-368. Retrieved September 20, 2017, from http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-024930

Schwartz, R. (2017, July 20). Tennessee Inmates are Being Offered a Horrifying Choice: Jail Time or Sterilization. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from https://splinternews.com/tennessee-inmates-are-being-offered-a-horrifying-choice-1797100263

Taussig, K-S., Rapp, R., & Heath, D. (2005). Flexible Eugenics: Technologies of the Self in the Age of Genetics. In J. X. Inda (Ed.), Anthropologies of Modernity: Foucault, Governmentality, and Life Politics (pp. 194-213). Malden, MA and Oxford: Blackwell. Retrieved October 10, 2017 from https://as.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu-as/faculty/documents/Flexible_Eugenics_2001.pdf

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Victims of the Nazi Era: Nazi Racial Ideology. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007457

Vasquez, T. (2017, January 30). ‘State of Eugenics’ Film Sheds Light on North Carolina’s Sterilization Abuse Program. Retrieved September 24, 2017, from https://rewire.news/article/2017/01/30/state-eugenics-sheds-light-north-carolinas-sterilization-abuse/

Wicked Silence [Video]. (2014, February 24). Retrieved September 20, 2017, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hstkagJJDfg

« Back to Glossary Index