Context,

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is a “state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community,” (WHO 2014). Guns and mental health is the perceived correlation of poor mental health and the use of guns to commit violent acts, such as what occurred in Columbine, Northern Illinois University, and Virginia Tech. According to Jonathan Metzl, “in each case, media connected the psychological instability of shooters to broader calls to limit gun rights for the mentally ill,” (Metzl 2011, 2172). However, media portrayal does not imply certainty. In fact, “little evidence supports the notion that individuals with mental illnesses are more likely than anyone else to commit gun crimes,” (Metzl 2011, 2172). It is estimated that people with a mental illness are involved in less than 3-5% of American crimes (Metzl 2011).

History,

The mentally ill have not always been seen as violent. In the United States, those with schizophrenia were viewed as docile for much of the first half of the 20th century. According to Jonathan Metzl, “From the 1920s to the 1950s, psychiatrists described it as a “mild” form of insanity that had an influence on people’s abilities to “think and feel”,” (Metzl 2011, 2172). Magazines described “schizophrenic poets producing brilliant rhymes” and “schizophrenic housewives” with mood swings (Metzl 2011, 2172).

It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that schizophrenia was linked with violence in the United States. The leading psychiatric journals published case studies discussing patients that exhibited criminality and aggression as symptoms of illness (Metzl 2011). Research from the University of Michigan showed that the changes in the diagnostic categories used to define mental illness, not an increase in violent action by people with mental illness, allowed for the emergence “schizophrenic violence,” (Metzl 2011). In 1968, paranoid schizophrenia was redefined to include hostility and aggression in its diagnosis. This then encouraged psychiatrists to view violence as a symptom of mental illness. American society contributed to this belief of the mentally ill being aggressive as the FBI Most-Wanted list described crazed “schizophrenic killers” and films depicted angry schizophrenics (Metzl 2011).

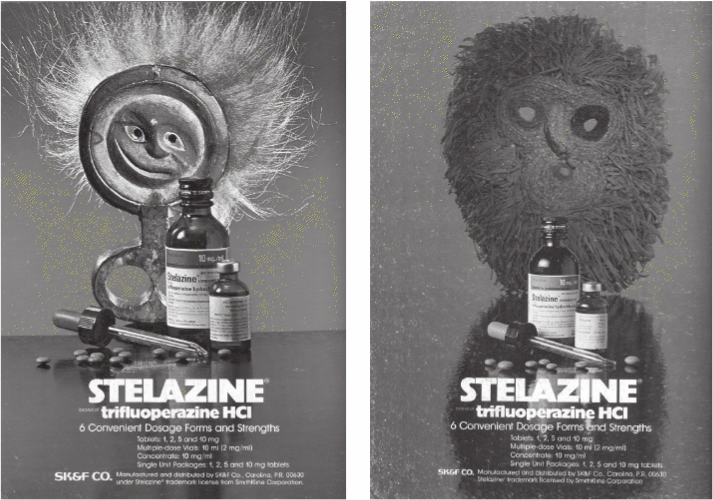

The change in views during the 1960s and 1970s also reflected changing anxieties about race. Jonathan Metzl said, “…many of the men depicted as being armed, violent, and mentally ill were, it turned out, African American,” (Metzl 2011, 2172). Newspapers, case studies in medical and psychiatric journals, and pharmaceutical advertisements promoted this link (Metzl 2011). An example of such advertisements can be seen in the image below. The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation also proclaimed links between African American men, violence, and mental illness. Malcolm X was diagnosed with “pre-psychotic paranoid schizophrenia” by FBI profilers, even though he was not schizophrenic (Metzl 2011). Fears of anti-government attitudes, guns, and sanity helped to move the public to sharing this view (Metzl 2011).

Image: 1970s advertisements for Stelazine, an anti-psychotic drug, in a medical journal linking psychosis to African heritage. From Jonathan Metzl, The Protest Psychosis, page 104

Perspectives,

As said by Dr. Anand Pandya, “Mental illness rarely features prominently in the nation’s priorities. During these rare opportunities, we may have an obligation to address common fallacies, (Anand 2013, 410). The 1993 Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act is considered to be the basis of federal gun control, named after James Brady, who was shot during the assassination attempt of President Reagan (Anand 2013). Key parts of this act attempted to limit firearm sales to those who had been convicted of a crime that was punishable by at least one year in jail, addicted to a controlled subject, or committed to a mental institution for example (Anand 2013). Since the conception of the 1993 Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, there have been multiple instances of mass gun violence, igniting debate on gun control and mental illness, with multiple perspectives arising.

A Swedish study found that “1 in 20 violent crimes were committed by patients with severe mental illness,” (Kramer and Verhulst 2013, 34). While there appears to be a connection to mass violence events and those committing them having a serious psychiatric disorder, this cannot be confirmed because “perpetrators of mass violence often do not survive the event, and may not have previously seen a psychiatrist,” (Kramer and Verhulst 2013, 34). In order to prevent the mentally ill from acquiring firearms, Kramer and Verhulst advocate for the expansion of state mental hospital systems and for the lowering of the threshold for legal commitment to these hospitals (Kramer and Verhulst 2013).

The majority of gun violence cannot be attributed mental illness (Gold and Less 2015). Because of this, “the APA (American Psychiatric Association) views the broader problem of firearm-related injury as a public health issue and supports interventions that reduce the risk of such harm,” (Gold and Lee 2015, 195). The APA advocates for background checks and waiting periods for those wishing to purchase firearms, as well as having a place to safely store them once they have been acquired (Gold and Lee 2015). The APA believes that if the characteristics of firearms are regulated to promote safe use, then it will be less likely that they will be used by anyone without the owner’s consent (Gold and Lee 2015). It also promotes banning firearms on the campuses of colleges and hospitals, except for those held by members of security teams and law enforcement (Gold and Lee 2015).

As mentioned by Kramer and Verhulst, many of those who commit mass acts of violence may have not previously been to a psychiatrist, thus it is not likely that they were previously diagnosed with a mental illness (Kramer and Verhulst 2013). With no prior diagnosis and the current prevention policy on disqualifying people from purchasing firearms, those with mental illnesses who seek to purchase firearms would be able to, thus failing to prevent a mass shooting. However, “prior to such a disqualifying event, family members, intimate partners, or others often observe a pattern of dangerous behavior,” (Frattaroli et al 2015, 292). To combat this, gun violence restraining order petitions can be entered in all 50 states (Frattaroli et al 2015).

Relation to Politics of Health,

The term guns and mental health is related to politics of health because it demonstrates the ability of the government and other institutions of shaping the public’s view on health. This ability can lead to the racialization of medications. As seen in the advertisement for Stelazine, an anti-psychotic drug promoted to those of African descent, there is a successful linkage of such lineage to schizophrenia (Metzl 2010). This could be compared to the development of BiDil, a heart medicine that reinforces the idea of biological races through its exclusive prescription to African Americans (Haga and Ginsburg 2006). However, with all humans having more than 99% of the same DNA sequence, there is not a case to be made for distinct racial classifications (Batai and Kittles 2013).

In addition to the racialization of medicine, government inference intensifying fears about black activist groups draws a strong parallel to the Black Panther Party. The Panthers were seen as a threat to national security. There were periodic police ambushes and the Federal Bureau of Investigations went to war with the party, especially in Oakland and Chicago (Greene 2016).

Bibliography

Batai, Ken and Rick A Kittles. “Race, Genetic Ancestry, and Health.” Race Soc Probl 5

(2013):81-87. Accessed October 15, 2017. Doi: 10.1007/s12552-013-9094-x

Frattaroli, Shannon Ph.D., M.P.H., Emma E. McGinty Ph.D, M.S., Amy Barnhorst M.D.,

and Sheldon Greengerg Ph.D. “Gun Violence Restraining Orders: Alternative or Adjunct to Mental Health-Based Restriction on Firearms?” Behavioral Sciences and the Law 33, no. 2-3 (June 2015): 290-307. Accessed October 15, 2017. Doi: 10.1002/bsl.2173.

Greene, Robert, II. “Remembering the Black Panther Party.” Jacobin Magazine, October

2016.

Haga, Susanne B. Ph.D. and Geoffrey S. Ginburg, M.D., Ph.D. “Prescribing BiDil: Is It

Black and White?” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 48, no. 1 (2006): 12-14. Accessed October 15, 2017. Doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.017

Kramer, Douglas A. M.D., M.S. and Johan Verhulst, M.D. “Guns, Violence, and Mental

Health: Did We Close the State Mental Hospitals Prematurely?” Psychiatric Times 30, no. 6 (June 2013): 34-35. Accessed October 14, 2017. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/docview/1372463852/fulltextPDF/E71B3CC5D3614792PQ/1?accountid=14816

“Mental Health: A State of Well-Being.” WHO. August 2014. Accessed September 22,

- http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/

Metzl, Jonathan M. “Gun violence, stigma, and mental illness: clinical implications.”

Psychiatric Times 32, no. 3 (March 2015): 54. Accessed September 22, 2017. http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?&id=GALE|A405023798&v=2.1&u=tel_a_vanderbilt&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&authCount=1

Metzl, Jonathan. Protest Psychosis : How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2010.

Metzl, Jonathan M. ““Why are the mentally ill still bearing arms?”.” The Lancet 377, no.

9784 (2011): 2172-173. Accessed September 22, 2017. Doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60950-1.

Pandya, Anand M.D. “The Challenge of Gun Control of Mental Health Advocates.”

Journal of Psychiatric Practice 19, no. 5 (September 2013): 410-412. Accessed October 14, 2017. Doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000435040.75802.90

Pinals, Debra A. M.D., Paul S. Appelbaum M.D., Richard Bonnie J.D., Carl E. Fisher

M.D., Liza H. Gold M.D., and Li-Wen Lee M.D. “American Psychiatric Association: Position Statement on Firearm Access, Acts of Violence and the Relationship to Mental Illness and Mental Health Services.” Behavioral Sciences and the Law 33, no. 2-3 (June 2015): 195-198. Accessed October 15, 2017. Doi:10.1002/bsl.2180.

« Back to Glossary Index