Loveis Jackson

History of African American Home Remedies

Definition and Background

The history of African American home remedies refers to generational practices that aimed to treat the mind, body, and soul holistically rather than medicinally. Home remedies rely heavily on natural substances and practices. Home remedies can be explicitly defined as “any substance that is not intended for medical purposes, which is used internally or externally for the cure, treatment, mitigation or prevention of disease or adverse-health related symptoms, or any drug that is obtained with a prescription or purchased without a prescription and used for medical purposes in a manner not intended by the prescriber or indicated on the product label” (Boyd, Shimp, & Hackney, 1984). In Stephanie Mitchem’s book African American Folk Healing, she provides examples of how home remedies were used in her childhood including “treating a nose bleed by holding a quarter on the back of the neck, using sweet oil drops to treat earaches, or rubbing sardine oil over a child with mumps” (Mitchem 1). These are just a few examples of the types of remedies used in the African American community. Doctor visits were to be a second line of defense only when home remedies couldn’t provide the cure. The term “home remedies” can be comparable with the term folk healing which Mitchem defines as “the creatively developed range of activities and ideas that aim to balance and renew life” (Mitchem 3). It is important to note the important role religion plays in these home remedies. It is the belief in a higher power that makes these remedies effective. In Kenneth Manning’s article, he points out that the “…most common ingredient [in home remedies] is a combination of incantations (the spiritual element) and herbal concoctions (the physical element)” (Manning, Kenneth R. “Folk Medicine”). Religion and natural substances were interconnected and successful healing required both. The use of home remedies does not necessarily mean that individuals deny going to the doctor; it simply means that doctor visits were a second line of defense only when a home remedy couldn’t provide the cure.

Image: Different herbs and spices with a pestle and mortar; source: Home Remedies Log

Historical Context

The origins of African American home remedies trace back to traditions that were brought over to America by slaves. In the African culture religion and medical customs were closely intertwined (Manning, 2006, 833). The physical condition was considered an outward display of one’s spiritual condition, which is why infirmities were treated with both the physical and spiritual element. In Eric Bennett’s article, he writes, “They (African Americans) believed that good health arose from harmony with nature and other people; poor health, from discord. Sickness could stem from either the curses of others, deviance from religious rectitude, or conflict with the natural environment” (Bennett, E. “Folk Medicine”). The use of home remedies established a belief in the interconnectedness between man, nature, and religion.

The use of home remedies were a result of forced segregation and racism. African Americans didn’t have the same rights or access to doctors as other white Americans did, which forced them to make their own cures and treatments. The use of home remedies was essential in the African American community for treating those with medical symptoms. The remedies used were based on the accessibility of the elements. In Mitchem’s book she states, “From curing a backache to smallpox, a variety of homegrown medical remedies utilized the elements at hand, such as black pepper, roots, and stones” (Mitchem 13). Slave owners eventually became accepting and even encouraging of this practice as this saved them money from having to hire a white practitioner (Manning, 2006, 833). This accepted practice allowed for a new class of “folk practitioners” to develop within the slave community (Manning, Kenneth R. “Folk Medicine”). These “folk practitioners” were also referred to as “root doctors or witch doctors” and were regarded with high esteem (Bennett, E. “Folk Medicine”). Usually the practitioner was an older woman (Jim Crow Encyclopedia, 2008). Although these traditions are accredited to African customs brought over by slaves, the use of them in America was because of the lack of medical access African Americans faced in America. Eventually these remedies became a part of African American traditions and these practices were passed down orally through generations (Covey 2007).

The use of home remedies also stemmed from African American’s rightly distrusting of white practitioners during times of slavery. This distrust of white practitioners was not solely accredited to harsh treatment, in terms of labor and conditions, of Blacks, but also because of the disregard of Black bodies. Procedures and experiments were performed on African Americans without their knowledge or consent. In Stephen Kenny’s Journal entry “Power, Opportunism, Racism: Human Experiments Under American Slavery”, he writes, “Slave patients proved indispensable to the medical education and successful practices of white southern doctors. Slave sufferers presented great opportunities for developing medical research, serving as useful human resources for producing knowledge and building white professional capital…” (Kenny 11). Slaves were viewed as a mechanism to gain more professional experience and accreditation, but these practitioners failed to get any type of consent or inform slaves of these trials. Kenny further goes on to quote medical researcher Todd Savitt who argues that “Slaves, as human commodities, were readily transformed into a medical resource, easily accessible as empirical test subjects, ‘voiceless’ and rendered ‘medically incompetent’ through the combined power and authority of the enslaver and their employee, the white physician” (Kenny 13). Mitchem mentions an example of this in her book, she states, “One example of the danger institutional health care posed to black people was sterilization programs. Programs that sterilized African Americans, without their knowledge, to end reproduction under the racial purity ideologies of eugenics grew during and after World War II, particularly in the South” (Mitchem 65). Another example of how black bodies were misused is the medical field can be seen through the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. The experiment was conducted between 1932 and 1972 in Tuskegee, Alabama where a group of white doctors denied treatment to about 400 African American men in order to study the effects of the disease (Jim Crow Encyclopedia, 2008).

Examples of Home Remedies

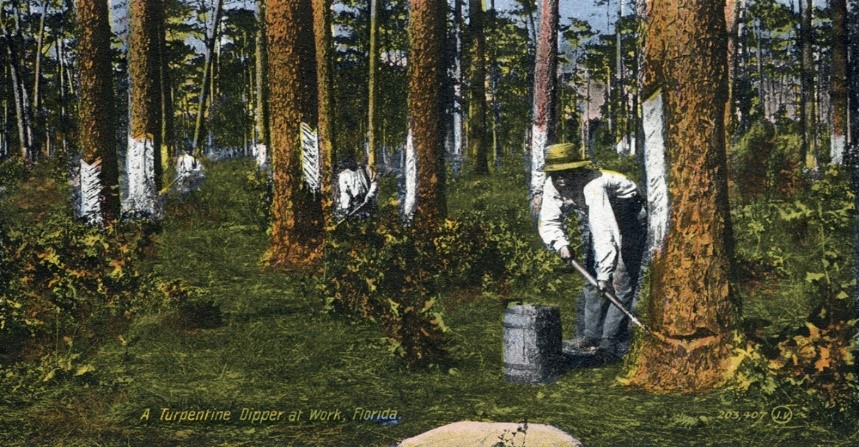

As outlined in Herbert Covey’s book African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments, some specific home remedies included the use of: asafetida, blackberry, cotton, castor oil, garlic, horseradish, rhubarb, sage, and the most common turpentine (Covey 81-89). There are numerous other elements used as home remedies, these are just a few examples. (If you would like more examples refer to Herbert Covey’s book.) Below are the specific uses of the elements named above as cited in Covey’s book.

- Asafetida: primarily worn around the neck as a preventative measure to ward off illness

- Blackberry: treatment of diarrhea

- Cotton: used to treat nauseas, fever, headache, diarrhea, and many other medical conditions

- Castor oil: used mainly to treat stomachaches and as a laxative

- Garlic: used to treat earaches, fungal skin infections, urinary tract infections, warts, pinworms, insect stings, bacterial and viral infections, and as a preventative measure

- Horseradish: the roots were used to treat respiratory ailments, digestive problems, gout, influenza, and medical ailments

- Rhubarb: used as a laxative, anti-inflammatory, and astringent

- Sage: used to treat loss of appetite, gastric disorders, diarrhea, bleeding gums, and many other symptoms.

- Turpentine: used to treat sore throats, cuts and bruises. (often times used with castor oil)

Image: Turpentine Dipper at Work, Florida; source: Sarasota County History Center

Continuity

One reason that home remedies in the African American community are still in use today stems from the mistrust of medical professionals. As cited in health literature, reasons for home remedy use are: “inadequate health education, poverty, less access to healthcare, skepticism of doctors, and racial and cultural differences between patients and providers” (Kong, Kong & McAllister, 1994). These types of disparities still exist in today’s society which is why the distrust of healthcare providers perpetuates and home remedies are still in existence. Individuals also tend to use home remedies over prescribed medications because of the numerous side effects of these prescribed medications (Boyd, Shimp, & Taylor 1997). According to Mitchem, another reason that these remedies haven’t died out is because it “continues to provide a cultural place where African Americans can define health or illness, care for their bodies, and utilize their spiritual concepts of a holistic universe” (Mitchem 78). These remedies are also still in use today because of the accessibility of the products. People no longer “walk in the yard to find the plant life needed for certain cures or fixes” rather they are accessible in drugstores (Mitchem 70). Mitchem writes about a pharmacist who opened his own drugstore which included in stock “castor oil, turpentine, simmer leaves, white oak and red oak bark, and asafetida” (Mitchem 70). Many of these elements are common ingredients used in or as a home remedy. Another reason that these remedies have not died out is because of their proven track record which has enabled individuals to provide holistic care for themselves and other individuals (Mitchem 2007).

Controversy

The controversy in the use of home remedies is the debate between the effectiveness of them. Are they doing more good than harm? Some see the use of home remedies as “bizarre, worthless, and even dangerous” (De Smet, 1991). The use of some home remedies such as the “oral ingestion of kerosene, turpentine, and mothballs” can be potentially dangerous (Snow 1974). Although most remedies, like eating chicken noodle soup or the use of different oils to treat different illnesses, are harmless using them to treat more serious conditions (heart problems, high blood pressure, etc.) can be harmful to the individual (Blum & Coe, 1977).They can provide a sense of false security that the medical condition is cured or less severe than what it is (Boyd, Shimp, & Taylor, 1997).The use of home remedies also delays individuals from seeking medical attention (Boyd, Shimp,& Taylor 1997). This can be detrimental as the condition for which a home remedy is used for can fail to receive the proper medical attention it needs. This also causes the condition to worsen, negatively impacting the individual. Home remedies are inherently harmless, but they can become dangerous when individuals who use them fail to recognize when a condition needs actual medical attention from a trained professional and instead rely solely on home remedies to treat them.

Contradictory, the use of home remedies can also be beneficial. The use of home remedies provides individuals with an understanding of health and how to maintain it. According to Audwin Fletcher “[The] understanding and relieving symptoms through home remedies may prevent unnecessary and difficult trips for formal medical services” (Fletcher 20). Being able to self-treat minor medical symptoms decreases over-visitation to doctor’s offices. It also allows the individual to have a better understanding of their own health and to be aware of their health status.

Relation to Politics of Health

The term African American home remedies relate to politics of health because it affects the dynamics of the relationship between health care providers and patients. The use of home remedies establishes a completely different system of health care system than the one that is already in place. In an excerpt from Bensoussan speech he says that “It is not simply a matter of offering health care in place of no health care at all; rather, it opens up a whole Pandora’s box of difficulties as to the clinical value of the complementary therapies relative to standard medical procedures” (Bensoussan, 1995). Using home remedies as the first response to medical conditions/symptoms forces health care providers to prove to their patients the worth of taking prescribed medications over using learned remedies. It also puts into question the credibility of the effectiveness of the treatments these health care providers are prescribing.

This term also relates to politics of health because it gives political etiology to a type of treatment for medical conditions. The term “political etiology” is what Nelson defines as “triangulat[ion] [of] biology with social environment and political ideology” (Nelson 4). Political etiology gives causation for a medical treatment or disease based upon social and/or political factors (Nelson 2013). Home remedies are seen in predominately African American communities because it is a result of African American’s denial of access to healthcare in the past. The use of home remedies in America started as a consequence of the forced segregation and racism African Americans faced.

Works Cited

Bennett, E. “Folk Medicine.” Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Second Edition, 2005, pp. Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Second Edition.

Bensoussan, A. (1995). In search of good health…excerpts from the speeches from Annual Conference Professional Day. Lamp, 52(7),35,37, 39

Blum, E.J. & Coe F.L. (1997). Metabolic acidosis after sulfur ingestion. New England Journal of Medicine 297, (16), 869.

Boyd, E.L., Shimp, L.A. & Taylor, S.D. (1997). Use of home remedies by African Americans. Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan, College of Pharmacy, Ann Arbor.

Boyd, E.L., Shimp. L.A., & Hackney, M.J. (1984). Home remedies and the black elderly: A

reference manual for health care providers. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute of Gerontology.

Covey, Herbert C. African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments. Lexington Books, 2007

De Smet, P.A.G.M. (1991). Is there any danger in using traditional remedies?

Journal of Ethnopharmacology,32, 43-50

Fletcher, Audwin Bernard. “African American Folk Medicine: A Form of Alternative Therapy.” ABNF Journal 11.1 (2000): 18-20. ProQuest. Web. 24 Sep. 2017.

“Herbs and Spices with Pestle and Mortar.” Home Remedies Log, 13 Aug. 2013, homeremedieslog.com/alternative-medicines/holistic/overview-3/.

Kenny, Stephen C. “Power, Opportunism, Racism: Human Experiments under American Slavery.” Endeavour, vol. 39, no. 1, 29 Mar. 2015, pp. 10–20., doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2015.02.002.

Kong, Kong, & McAlister (1994). Politics and health: The coming agenda for a multiracial and multicultural society. In: Livingston, I.L. ed. Handbook of Black American Health: The Mosaic of Conditions, Issues, Policies, and Prospects. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Manning, Kenneth R. “Folk Medicine.” Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. Ed. Colin A. Palmer. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2006. 833-834. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Mitchem, Stephanie. African American Folk Healing, NYU Press, 2007. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Nelson, Alondra. “Spin Doctor The Politics of Sickle Cell Anemia.” Body and Soul: the Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination, University of Minnesota Press, 2013, pp. 4–5.

Sarasota County History Center. “A Turpentine Dipper at Work, Florida.” Sarasota History Alive.

Snow, L.F. (1974). Folk medical beliefs and their implications for care of patients: A review bases on studies among black Americans. Annals of Internal Medicine, 81 (1), 82-96.

The Jim Crow Encyclopedia: Greenwood Milestones in African American History, edited by Nikki L. M. Brown, and Barry M. Stentiford, ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central

« Back to Glossary Index