A Background on Hospice Care and Its History in the United States

Hospice care is a form of medical care and social support provided for individuals with less than six months to live. The focus is on caring for the patient and alleviating their pain, not on curing the disease. Usually care is administered in the patient’s home, but hospice care can also take place in a hospital, nursing home, or an independent hospice center (“Hospice Care,” National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization). A family member is usually the primary caregiver, with a constantly on-call team comprised of physicians, nurses, home health aides, social workers, clergy or other counselors, trained volunteers, and speech, physical, and occupational therapists. The composition of this team can be altered based on the patient’s needs, and the family member is able to make decisions for the patient if they are unable to (“Hospice Care,” National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization). The video “Understanding Hospice Care” shows the President of the non-profit National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, Donald Schumacher, providing basic information that someone seeking hospice care may want to know for themselves or their loved one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cK3tpXwfuhE.

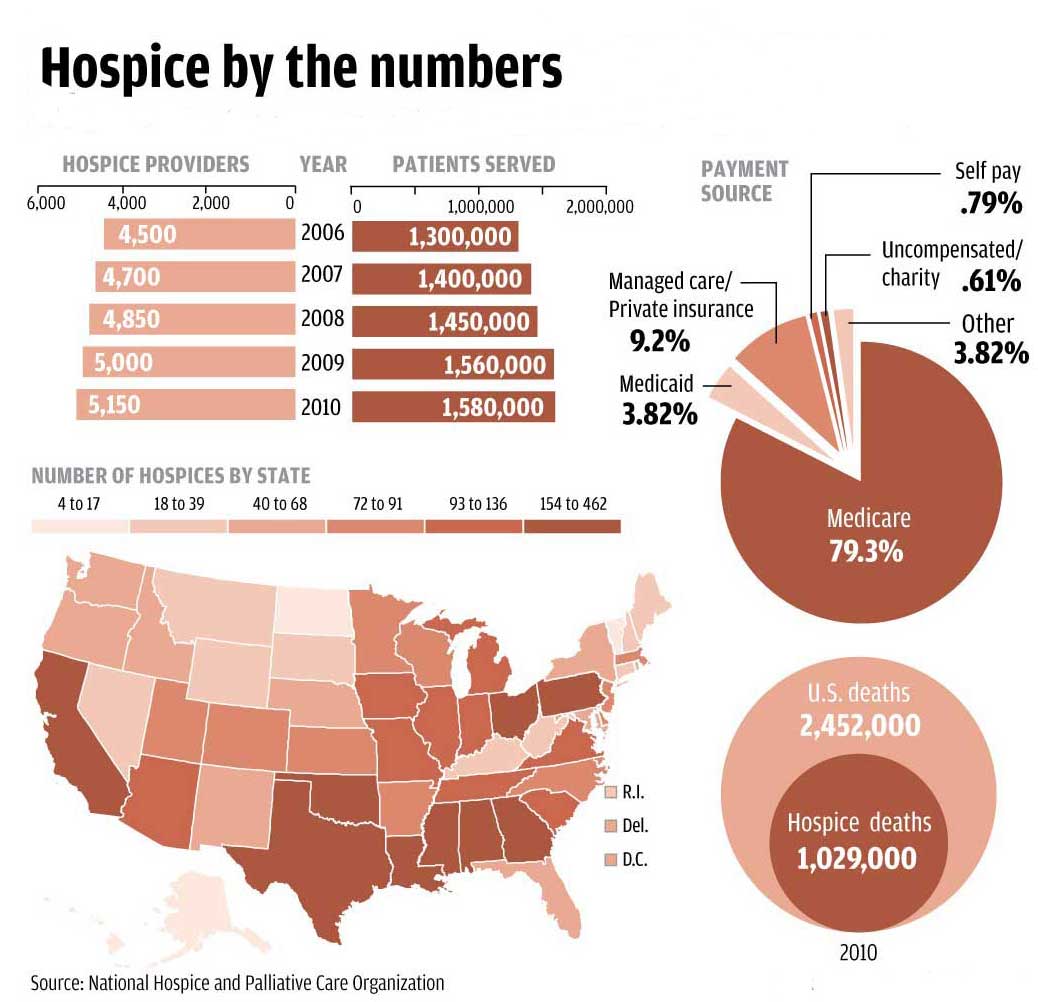

As of 2013-2014, there are 4,000 hospice care agencies operating in the United States serving approximately 1.3 million patients (“Hospice Care,” CDC). However, the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), a non-profit organization advocating for hospice patients and programs, puts that number higher. As shown in Fig. 1, the number of patients and agencies has increased over time. The median length of hospice care is slightly under 3 weeks, with 35% of patients being discharged or dying within 1 week of admission (Morrison).

Fig. 1: A graphical breakdown of the number and distribution of hospice patients and agencies in the United States (NHPCO).

Hospice care was introduced in the United States by Florence Wald, the former Dean of Yale University’s School of Nursing, when he returned from a trip to a hospice in England (Morrison). He established the Connecticut Hospice in 1974, and soon after the hospice concept was recognized as potentially helpful for Americans suffering from terminal illnesses (Morrison). It has since grown and become more widespread.

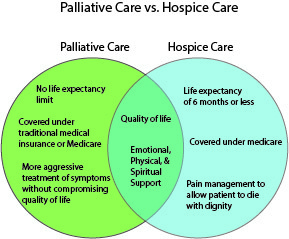

Hospice care is related to palliative care, which is designed to aid patients with incurable diseases. However, palliative care can begin when the condition is diagnosed. Below, Fig. 2 shows the relationship between hospice care and palliative care.

Fig. 2: A Venn diagram showing the similarities and differences between the terms palliative care and hospice care (Dumke).

Perspectives on Hospice Care and Its Modern Context

The primary debate on hospice care centers around whether or not it is ultimately good for the patients. Many people believe that hospice care helps people live the remainder of their lives comfortably and spend their time how they would like. For example, Robert Gregg suffered a stroke and has lost many of his memories, but music therapy has helped him stay positive during the difficult times (“Mr. Gregg: The Life of the Party”). These patients and their families assert that being in a more medicalized environment or being subject to more aggressive treatment would not have made their last days as comfortable. Many more such stories can be found at “Moments of Life” (https://moments.nhpco.org/), a website dedicated to sharing the positive experiences of individuals who were in hospice care.

However, some people view hospice as hastening death and believe that this type of treatment does not necessarily help their loved ones. One example given by some family members on an online forum involves the use of drugs like morphine and Ativan; they say that these medications made their relative(s) very “out of it” and less like themselves during their final days (“Did Hospice rush your loved ones death?”). Another potential attack on hospice care is that 60.2% of agencies in the United States are for profit as of 2014 (“Hospice Care,” CDC). While hospice may have originated as a social movement to help the dying, it has become a lucrative industry due to Medicare reimbursement (Gleckman).

In addition to these opposing perspectives, there is a racial discrepancy in opinion about hospice care. According to a 2008 study conducted by Duke University, “African Americans were more likely [than white Americans] to express discomfort discussing death, want aggressive care at the end of life, have spiritual beliefs that conflict with the goal of palliative care, and distrust the healthcare system” (Johnson et al.). This study also found that only 35.5% of African Americans had an advance directive in opposed to 67.4% of whites (Johnson et al.). An advance directive is a document stating a person’s decisions regarding their medical care at the end of their life; this allows their wishes to be carried out, even if they are not able to directly communicate with their health care provider(s). A situation in which the patient leaves no advance directive may put their family in a difficult position, where they must try to figure out what their loved one would want. Some African American clergy and doctors are advocating for the broader use of hospice care in their communities: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/25/health/a-racial-gap-in-attitudes-toward-hospice-care.html. This article also addresses some of the discrimination African Americans face when they seek end of life care. By sharing their individual stories, some black families are trying to eliminate the negative stigma associated with hospice care.

How is Hospice Care Connected to “Politics of Health” concepts?

In the modern United States, the natural process of dying has become highly medicalized. Hospice care is a way of reclaiming someone’s last days and spending them how they would like – not necessarily in a hospital or attached to life support. This type of care is a form of demedicalization, as it focuses on more social and spiritual aspects of dying by helping the patient and family cope with the situation. Under the umbrella of demedicalization, I also think that hospice care represents a form of depharmaceutalization. Instead of pursuing advanced treatments for a disease, patients are opting simply to alleviate pain or turning to alternative forms of dealing with their illness, such as physical therapy. Even though hospice care is usually administered in someone’s home and is a less medicalized way of dying, it is worth pointing out that it is still a medical system: note that the majority of a patient’s “team members” are health professionals.

In addition to medicalization, Foucault’s concept of biopower applies to hospice patients. The various medical professionals, social workers, and family members all exercise some degree of control over the patient and their body. This control becomes more even obvious in specific aspects of care: for example, when a family member is able to make decisions for the patient if they are considered of incapable of deciding for themselves (“Hospice Care,” NHPCO). However, not all aspects of the biopower associated with hospice care are negative. Anthropologist Michael Anstice argues that in this case, biopower can be liberating for the patient, saying that “a focus on life for those facing inevitable death is beneficial for patients so they can find some solace at end-of-life.” People in hospice know that they will not get better and are instead trying to live the best lives they can with the little time they have left. In this way, “the life-centric focus of biopower manages and optimizes the remaining lives of patients” (Anstice).

Hospice care remains an often overlooked and under-utilized aspect of the American health care system; the fact that the median length of care is approximately three weeks shows that patients are referred too late (Morrison). While there are some objections based on personal views and concerns about profit motives, hospice care is a viable option for many individuals looking to alleviate pain at the end of their lives.

Works Cited

Anstice, Michael R. Hospice and the Point of No Return: The Intersections of Life, Inevitable Death, and Biopower. MA thesis. Texas State University, 2014.

“Did Hospice rush your loved ones death?” Aging Care.com. https://www.agingcare.com/discussions/did-hospice-rush-your-loved-ones-death-162802.htm. Accessed 14 April 2018.

Dumke, Caroline. “What’s the Difference between Palliative and Hospice Care?” Life-Links, October 2013. http://hosted-p0.vresp.com/581252/d39195d57c/ARCHIVE. Accessed 14 April 2018.

Gleckman, Howard. “What’s Behind the Criticism of Hospice? Is It Fair?” Forbes, 11 September 2014. https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2014/09/11/whats-behind-the-criticism-of-hospice-is-it-fair/#4955294552b2. Accessed 14 April 2018.

[Home Page]. Moments of Life. https://moments.nhpco.org/. Accessed 9 April 2018.

“Hospice Care.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 6 July 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/hospice-care.htm. Accessed 9 April 2018.

“Hospice Care.” National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 4 April 2017. https://www.nhpco.org/about/hospice-care. Accessed 9 April 2018.

Johnson et al. “What Explains Racial Differences in the Use of Advance Directives and Attitudes Towards Hospice Care?” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 56, no. 10, 1 October 2008. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01919.x. Accessed 9 April 2018.

Morrison, R. Sean. “Models of palliative care delivery in the United States.” Current opinion in supportive and palliative care 7.2 (2013): 201-206. PMC.

“Mr. Gregg: The Life of the Party.” Moments of Life. https://moments.nhpco.org/stories/mr-gregg-life-party. Accessed 14 April 2018.

“Understanding Hospice Care.” YouTube, uploaded by NationalHospice, 3 March 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cK3tpXwfuhE. Accessed 13 April 2018.

Varney, Sarah. “A Racial Gap in Attitudes Toward Hospice Care.” New York Times, 21 August 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/25/health/a-racial-gap-in-attitudes-toward-hospice-care.html. Accessed 14 April 2018.

« Back to Glossary Index