Institutional Review Boards

Background

Institutional Review Boards, or IRBs, are ethics committees designed to evaluate federally funded research projects in order to prevent the inhumane maltreatment of their subjects, insofar as the risk posed cannot be justified by the anticipated benefit (IRB Guidebook, 1993). They consist of 5 or more impartial investigators possessing “competencies necessary in the judgment as to the acceptability of the research in terms of institutional regulations, relevant law, standards of professional practice and community acceptance”, thereby requiring at least one non-scientist, and potentially calling for input from an advisory council with formal expertise regarding the field in question (Curran as qtd. by Levine). All research projects involving human subjects are restricted by federal regulation; furthermore, those funded by a university or other institution require oversight by a federally approved IRB within their institution, consisting of at least one reviewer not affiliated with the institution, and no members with demonstrated conflicting interest (Darity, 2008). In addition, after submitting the details of their research design for inspection, approved long-term studies must be reviewed at least once a year, while certain projects with very minimal risk may apply for expedited review or waive the process entirely (Lavrakas, 2008). Such groups were instituted in response to unethical research practice in the U.S. and abroad, as the 93rd U.S. Congress signed into action the National Research Act of 1974, which requires:

“that each entity which applies for a grant or contract under this Act for any project or program which involves the conduct of biomedical or behavioral research involving human subjects submit in or with its application for such grant or contract assurances satisfactory…[that it has established] a board (to be known as an ‘Institutional Review Board’) to review biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects conducted at or sponsored by such entity in order to protect the rights of the human subjects of such research” (National Research Act, 1974).

Similarly, according to the IRB entry in volume 4 of Bioethics, the Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), in issuing its International Ethical Guidelines, sets the following standard for biomedical research: “All proposals to conduct research involving human subjects must be submitted for review of their scientific merit and ethical acceptability to one or more scientific review and ethical review committees” (CIOMS as qtd. by Levine, 2014).

Context

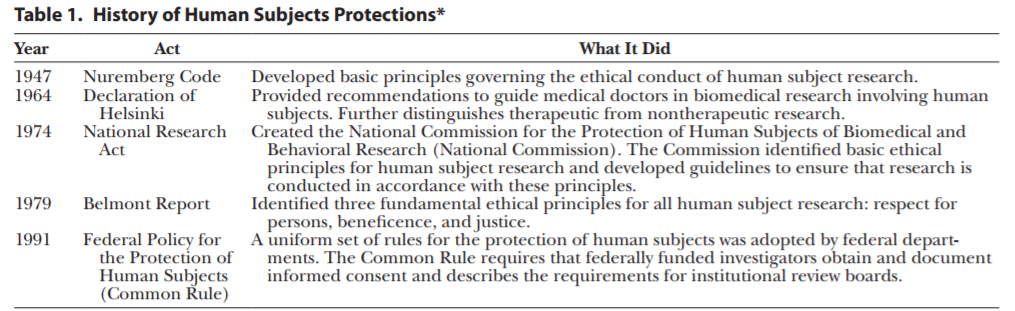

As was suggested, the National Research Act–and by consequence, Institutional Review Boards–was largely established in response to the disquieting ethical misconduct exposed throughout the mid-twentieth century (Briggle, 2015). This includes, but is not limited to, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, unethical research performed by Nazi scientists, Milgram’s electric shock experiments, project MKUltra, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the intentional infection of mentally disabled persons with hepatitis (Resnik, 2017). Specifically, the Nuremburg Code (1947), which arose in light of the medical experiments performed in Nazi concentration camps during World War II, set the following standards, which have carried into the “declarations and endorsements of professional codes of conduct” around the world:

“these tenets include: (1) the ability to voluntarily participate or withdraw from participation; (2) the freedom from coercion to participate; and (3) the right to be informed of all potential risks and benefits of participation. Furthermore, the code’s provisions require that researchers be professionally qualified for the specific type of research in question, that they use appropriate research designs, and that they seek to minimize the risk of potential harm to human subjects” (Darity, 2008)

In the U.S., similar unethical experimentation spurred the development of its own such code. For instance, in 1963, Stanley Milgram published the results of his “electric shock experiment” wherein:

“one human subject was asked to deliver electrical shocks of increasing voltage to another person who was secretly collaborating with the experimenter. Even though the shocks were fictitious, the screams and pleas of the collaborator led the subject to believe that they were real. Ironically, Milgram’s motivation for the study was the psychology behind the Nazi atrocities” (Darity, 2008).

In light of this high-profile case, posing serious emotional or psychological risk, the NIH issued the “Policies for Protection of Human Subjects” three years later (Darity, 2008). Furthermore, in 1972, another controversial study by the U.S Public Health Service caught national attention (Darity, 2008). Dubbed the “Tuskegee Syphilis Study”, unethical research involving “a decades-long clinical study of the effects of syphilis using a sample of several hundred, mostly poor, African Americans living near Tuskegee, Alabama” renewed national interest in the protection of human research subjects (Darity, 2008). Likewise, in this study:

“While some subjects were given proper treatment, others were not informed of their diagnosis and were prevented from receiving treatment from other health-care providers. The primary goal of the Tuskegee study was to determine how, over extended periods of time, syphilis affects the human body and eventually kills. Not only did many human subjects in this experiment die from nontreatment, but the disease was also spread to the spouses and children of the untreated participants. The Tuskegee researchers did not receive the informed consent of the subjects and did not disclose the risks of participation to them and their families” (Darity, 2008).

As a result, the Tuskegee Study, like the Milgram experiments, invoked questions of beneficence and respect, while further introducing the notion of indiscriminate recruitment. Two years later, the National Research Act was passed, establishing institutional review boards under the “National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research” (Darity, 2008). Regulations established by this commission’s Belmont Report (1979) “served as the basis for the subsequent revisions to the federal regulations, which eventually evolved into the current Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects”; this policy has been largely adopted across U.S. institutions and is often referred to as the “Common Rule” (1991) (Darity, 2008). The Belmont Report and Common Rule reinforce the commitment of research to ethical principle, mandating “value, scientific validity, fair subject selection, favorable risk-benefit ratio, independent review, informed consent, and respect for enrolled subjects” (Darity, 2008). These principles stem from a set of core assumptions, namely: “respect for human dignity” entitling one to informed consent, “balancing of harms and benefits” requiring minimal risk and maximal benefit to society, and “justice” prohibiting disproportionate harm or benefit to a particular group (Given, 2008).

Results of influential research policy ordered by year—IRB Guidebook

Finally, “the technological revolution of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries”, specifically, the “several high-profile cases of careless procedures during medical drug trials” reinforced IRB adherence to the Common Rule, tightening regulation of local research projects, which consequently developed debate as to its efficacy and proper application (Darity, 2008). However, on January 19, 2017, the Federal Register published a new set of revisions to the Common Rule, seeking to decisively “implement new steps to better protect human subjects involved in research, while facilitating valuable research and reducing burden, delay, and ambiguity for investigators” (OHRP, 2017).

Perspectives

On the one hand, institutional review may be “essential for the protection of human subjects” or, at the very least, “has improved research practices by making researchers aware of ethical norms and exercising the power to withhold approval for substandard proposals” (Briggle, 2015). On the other, researchers have claimed that “the IRB system is under strain and in need of reform, and significant doubt exists regarding its capacity to meet its core objectives” (Briggle, 2015). According to Ethics, Science, Technology, and Engineering: a Global Resource, some specific points of contention include: the “decentralized structure of the system”, the “proper scope of IRB authority”, and “who should conduct IRB review” (Briggle, 2015). On the contrary, implementation of the supplementary “Final Rule” to IRB protocol in 2017 may prove to at least mitigate some of the common concerns regarding its regulation.

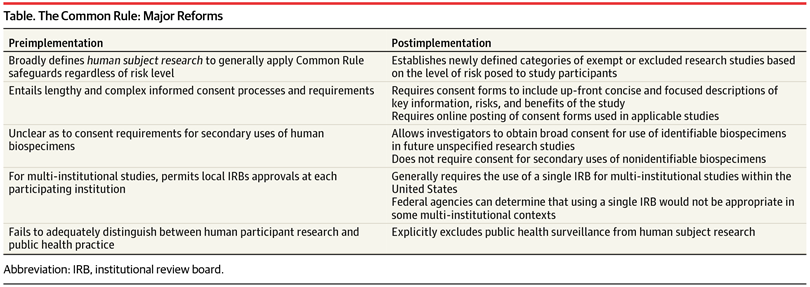

Major Effects of Common Rule Reform—American Medical Association

Indeed, critics—particularly in the social sciences—of the Common Rule and IRB procedure claim it is unnecessarily stringent for particular modes of research, generally pointing to the impracticality of securing informed consent and submitting a precisely articulated overview of (possibly evolving) studies before they begin (Given, 2008). Such critics suggest that IRB application of the Common Rule stifles the scientific climate with the scrutiny imposed by burdensome regulation (Darity, 2008). Accordingly, any research does, in fact, fall under jurisdiction of the Common Rule so long as it involves “a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge”, while IRBs reserve the right to exempt any given class of academic pursuit (Darity, 2008). Similarly, critics argue that “studies with serious design flaws that could lead to unethical practices or participant harm continue to win approval because IRBs are too lax…and are overwhelmed by the volume of studies they must review” (Sabriya, 2015). Indeed, Kotsis and Chung note that “As of May of 2013, there were more than 146,000 clinical trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov.7 This number is up from 5645 studies that were registered in 2000, when the Web site debuted” (Kotsis and Chung, 2015). Moreover, “Total spending on health-related research and development by pharmaceutical companies and the federal government is estimated to have tripled since 1990” (Kotsis and Chung, 2015). However, Dr. J. Menikoff, in his commentary on the updated Common Rule for the New England Journal of Medicine, suggests that the new regulation actually facilitates a shift from devoting too much unnecessary oversight toward low-risk studies to instead focusing on the protections in studies with relatively higher risk, as it “creates additional exemptions for low-risk studies, eliminates the need for continuing review for many studies, and provides a new option for facilitating the screening of potential participants” (Menikoff, 2017). Just so, the Final Rule exempts from review “educational studies, behavioral assessments, public benefit program reviews, and secondary studies of stored biospecimens entailing minimal risks or conducted with “broad” consent” (Hodge, 2017). Finally, James Hodge, JD, writing for the American Medical Association, points out that the rule also reduces administrative burdens on review boards, as it:

“(1) clarifies IRB procedures for research approval; (2) dispenses with onerous reviews of grant applications, contracts, and ongoing minimal-risk studies (eg, data analyses); (3) requires (in 3 years) single IRB approval and oversight of multi-institutional research (unless tribal or state laws mandate additional IRB review); and (4) facilitates online tools to help IRBs assess an expanded array of “exempt” or “expedited” research” (Hodge, 2017).

Regarding this third directive, Hodge notes that “Research enterprises now encompass vast multicenter trials in both academia and the private sector”, which poses a problem for IRB efficiency, insofar as each institution would require a separate review for multi-institutional studies (Hodge, 2017). However, the Final Rule addresses this precise concern, as Menikoff notes:

“The new rule adopts the proposal to generally require single-IRB review for multi-institutional studies conducted in the United States. In response to public concerns, while the rule establishes single-IRB review as the default, it allows any federal agency supporting or conducting research to determine that the use of a single IRB is not appropriate for a particular context…The goal of encouraging the use of single-IRB review in this way is to empower that IRB to better protect all human participants in a given study, while eliminating the time and effort associated with multiple IRB reviews and the need for reconciling different IRB determinations” (Menikoff, 2017).

Moreover, the original Common Rule lacked any distinction “human participant research” and “public health practice”, which greatly hindered public health agencies (Hodge, 2017). While “surveillance and other epidemiologic investigations gather personal information and can generate generalizable knowledge”, which would classify them as research pending approval, “these activities are vital to public health, with the primary goal of safeguarding populations” (Hodge, 2017). And, as a result, “Requiring IRB approval forced health departments to curtail, restructure, or discontinue important activities” (Hodge, 2017). On the contrary, the Final Rule makes the following stipulation:

“In defining research, the rule explicitly exempts the newly defined classification of public health surveillance, broadly worded to include an array of public health practice activities. As a result, governmental agencies and their contracted partners can undertake routine and emergency “public health surveillance activities” without IRB review and approval” (Hodge, 2017).

Lastly, researchers have opposed the obligation of IRBs to “approve or disapprove the scientific design of research protocols” (Levine, 2008) On the one hand, it would seem necessary for comparison of risk with the anticipated benefit to know whether “the scientific design is adequate”; certainly, if an inadequate project poses no benefit, then any risk at all should invalidate it (Levine, 2008). However, researchers also contend rightly that “the IRB is not designed to make expert judgments about the adequacy of scientific design” and “assessment of scientific validity is, and ought to be, delegated to committees designed to have such competence—such as scientific review committees either within the institution or at funding agencies such as the National Institutes of Health”, drawing a clear boundary between ethical and scientific judgement, while expressing the limited nature of institutional review (Levine, 2008).

Politics of Health

Finally, Institutional Review Boards impact the politics of health as mediators of knowledge production which mandate the informed consent of research participants. One may question the impact of institutional review on the output of scientific information, as to whether a biopolitical entity (e.g. the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in conjunction with the federal government, accredited research-universities, etc.) could have influence over produced knowledge by retaining the capacity to deny certain academic pursuits. Although, the dispersive model of regulation by independent committees would seem to inhibit any sort of large-scale discrimination of knowledge, while the significant increase in research output despite institutional review would evidence against any overall downregulation (Kotsis and Chung, 2015). Furthermore, Ethics, Science, Technology, and Engineering: a Global Resource, also points out that “the Belmont Report represents a rare instance of the federal government formally accepting a moral theory as the foundation for legislation” (Briggle, 2015). In imposing the Hippocratic moral standards of beneficence, respect, and justice, as they are interpreted in the report, a governing body does in a sense arbitrate knowledge which impacts the general populace, though it would seem largely necessary to prevent the sorts of morally atrocious experiments from which the code was born (Briggle, 2015).

In addition, regarding research participation, in “Ready-to-Recruit” or “Ready-to-Consent” Populations?: Informed Consent and the Limits of Subject Autonomy, Dr. Jill Fisher offers a theoretical model for understanding consent, where her article focuses on “one particular framing of human subjects – both in the U.S. and globally – as populations that are “ready to recruit” for clinical trials”. These populations are generally marginalized in some way, and so unduly and disproportionately pressured into research participation for lack of alternatives, leading to ready exploitation by industry-affiliated research (Fisher, 2007). Likewise, opponents of institutional review may seek revision in informed consent policy, suggesting that it further protect marginalized subjects from incentives to risky treatment, or that it heighten restrictions on research in developing countries. Indeed, under the original Common Rule, which required consent forms to be exhaustively detailed, Hodge contends, “Informed consent forms, the bulwark of protection, ballooned to the point that many participants could not fully understand the risks and benefits—the forms became more a hedge against institutional liability than a promotion of human dignity and autonomy”, which would prejudice less educated participants and, insofar as no reasonably attentive person could recognize that to which he was assenting, would undermine the purpose of procuring consent forms in the first place (Hodge, 2017). However, the new regulation greatly simplifies the nature of these forms, enabling subjects of varying educational backgrounds to “better understand the scope, risk, and benefits of research” by requiring a “concise, up-front explanation of information a “reasonable” person would desire, such as purposes, risks, benefits, and alternative treatments” (Hodge, 2017).

Moreover, Drs. Stephanie Park and Mitchell Grayson published a report in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology questioning the benefit IRBs really offer vulnerable populations. They suggest, “Current ethical guidelines prohibit or severely limit what types of research can be performed involving [them]. Although this might protect these populations, the lack of research on them might actually do harm in limiting their access to life-saving therapies” (Park and Grayson, 2008). Similarly, in her work on Informed Refusal: Toward a Justicebased Bioethics, Ruha Benjamin offers a unique understanding of vulnerable populations, as she says, “a key feature of social marginalization in the context of biomedicine is that subordinate ethnoracial groups are typically situated at the deadly intersection of medical abandonment and overexposure” (Benjamin, 971). Certainly, striking a balance between protecting vulnerable populations from exploitative research, while still allowing them the medical attention necessary for their overall health, remains a critical component of institutional review, as can be seen from its distinction of human research participation and public health practice mentioned previously.

Finally, anthropologist Cori Hayden suggests that scientific knowledge ‘‘does not simply represent (in the sense of depict) ‘nature,’ but it also represents (in the political sense) the ‘social interests’ of the people and institutions that have become wrapped up in its production’’ (Hayden as qtd. by Benjamin, 983). Likewise, the Common Rule contains a sort of political disentanglement, requiring IRBs to have on their committee at least one non-scientific member representative of the general populace and one non-affiliated with the institution sponsoring the project, while prohibiting any conflicting interest that could serve to bias the approval of certain research; as a result, specifications for committee membership effectively distance institutional review boards from the production of knowledge (Levine).

In conclusion, Institutional Review Boards are an ongoing product of history, vitally tied to the politics of health and its preservation.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Ruha. “Informed Refusal.” Science, Technology, & Human Values.

Briggle, Adam. “Institutional Review Boards.” Ethics, Science, Technology, and Engineering: A Global Resource, edited by J. Britt Holbrook, 2nd ed., vol. 2, Macmillan Reference USA, 2015, pp. 563-566. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Accessed 19 Nov. 2017.

Fisher Jill A. ‘Ready-to-Recruit’ or ‘Ready-to-Consent’ Populations? Informed Consent and the Limits of Subject Autonomy. Qualitative Inquiry. 2007;13(6):875–94.

“Institutional Review Board.” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, edited by William A. Darity, Jr., 2nd ed., vol. 4, Macmillan Reference USA, 2008, pp. 42-43. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Accessed 15 Nov. 2017.

“Institutional Review Boards.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, edited by Lisa M. Given, vol. 1, SAGE Publications, 2008, pp. 439-440. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Accessed 15 Nov. 2017.

IRB Guidebook: Introduction, Office for Human Research Protections. 1993.

- Menikoff, J. Kaneshiro, I. Pritchard. “The Common Rule, Updated” N. Engl. J. Med.,376 (2017), pp. 613-615. Accessed 15 Nov. 2017

James G. Hodge Jr, JD, LLM. “Modernizing the US Federal Common Rule for Human Participant Research.” JAMA, American Medical Association, 18 Apr. 2017.

Kotsis, Sandra V., and Kevin C. Chung. “Institutional Review Boards: What’s Old? What’s New? What Needs to Change?” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 7 Oct. 2015.

Levine, Robert J. “Institutional Review Boards.” Bioethics, edited by Bruce Jennings, 4th ed., vol. 3, Macmillan Reference USA, 2014, pp. 1734-1739. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Accessed 15 Nov. 2017.

Office for Human Research Protections. “Final Revisions to the Common Rule.” HHS.gov, US Department of Health and Human Services, 19 Jan. 2017.

Resnik, David. “Research Ethics Timeline (1932-Present).” National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017.

Rice, Sabriya. “Policing the Ethics Police.” Modern Healthcare, vol. 45, no. 50, 14 Dec. 2015, p. 0018. EBSCOhost.

S.S. Park, M.H. Grayson. “Clinical research: protection of the vulnerable?” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 121 (2008), pp. 1103-1107. Accessed 15 Nov. 2017.

« Back to Glossary Index