Background

The Love Canal Tragedy is oftentimes synonymous with the “worst environmental disaster involving chemical wastes in U.S. history” (“Love Canal.” 1). The Love Canal tragedy was an accumulation of environmental, economic, and public health issues all in one. Love Canal was a neighborhood located in Niagara Falls, New York. The name of the neighborhood was derived from William J. Love, a local entrepreneur. In 1894, William J. Love began the construction of a canal between the upper and lower Niagara Rivers. After digging a distance of 3,000 feet, Love’s project lapsed due to finances (Worthley). Eventually, the Love Canal area became an abandoned canal where chemicals were buried. In the 1940’s and 50’s the Hooker Chemicals and Plastics Corporation produced nearly 22,000 tons of chemical waste which was dumped into the Love Canal area. The drums that were used for chemical disposal were originally built to retain water, not toxic chemicals. Water is not able to corrode these waste disposal drums like toxic chemicals do. In fact, the chemicals caused the barrel drums to rust and become unreliable. In 1953 once the site was covered and the land was presumed safe, the company sold the land to the city and housing was built (Worthley).

By 1958 more than 100 homes had been built, and 100 more homes were added by 1970 (Worthley). As early as 1959, indications of health hazards began to appear (Worthley). Children received chemical burns while playing near the canal, residents noticed black sludge bleeding through basement walls, and chemical odors in their basements were present (Worthley). Eventually the State Department of Environmental Conservation began inspections due to numerous complaints. In 1978, state officials detected the leakage of toxic chemicals from underground into the basements of homes (“Love Canal.”). Due to the long-term exposure to toxic chemicals, residents experienced various inexplicable health problems. There were high incidences of problematic pregnancies, miscarriages, and birth defects.

Soon after the discovery of these health hazards, the Task Force demanded the relocation of families, the prevention of further movement of toxic chemical waste through construction projects, and the continuation of the health and environmental aspects (Worthley). The American Red Cross, Salvation Army, and United Way of Niagara Falls helped the relocation process of residents. This event led to the creation of the Superfund program by the U.S. Congress in 1980 where billions of dollars were authorized toward site remediation (“Land Pollution”). The State also entered an agreement with the United Way of Niagara Falls which provides longer-term medical, mental health, recreation, and information referral services (Worthley). After litigation, 1,300 former residents of the Love Canal neighborhood agreed to a $20,000,000 settlement of their claims (“Love Canal.”).

Controversy

The environmental crisis that took place at Love Canal was the catalyst of the environmental health movement (Paigen). Overall, the general view was that the local government was not equip to prevent or restore an issue of this magnitude. Therefore the community turned to the state and federal government. Originally, the Hooker Chemicals and Plastics Corporation sold the toxic dump to the city for one dollar. Due to the lack of preexisting environmental protections, these decisions merely rely on business and economic motivations (Paigen). Because the goal of industry is profits, the community did not entirely blame the Hooker Chemicals and Plastics Corporation. In fact, they were more frustrated with the New York State Department of Health. In this case they believed that the Health Department was knowledgeable about toxic chemicals and neglected to protect the health of the community. Scientists at the New York State Department of Health “acknowledged elevated rates of illness and death at Love Canal, yet unable to prove disease causation, they refrained from stating causality” (Thomson 207). The unwillingness of scientists to make claims led to a delayed evacuation. Because the salaries of the officials came from the community’s tax money, the community argued that the department was inconsistent with its responsibilities and minimized severe health risks (Paigen).

Lois Gibbs, a former resident of Love Canal, became one of the leaders of the environmental health movement. Her passion towards the issue started when she connected her son’s seizures and low blood count to the fact that toxic chemicals were buried underneath his school. As she and her neighbors learned more and more about the dangers of toxic chemicals, they pushed for local action through protests, but they were ignored. The New York State Department of Health initially only cited a probable risk to fetal development and childhood development. Therefore, only 26 residents were temporarily evacuated. These residents included six pregnant women and 20 children (Fowlkes). The narrow criteria for this evacuation created strong opposition from residents who were not willing to accept that the health risks could be known while the boundaries and effects of the chemical migration were uncertain (Fowlkes). Gibbs led the citizen protests at Love Canal and once the entire country began to learn about their struggle, a media firestorm was created. A week later, the state issued the relocation of families, the passage of new environmental legislation, and a newfound national awareness of the health hazards of toxic chemicals (Gibbs). The concern for health and the desire for justice and human rights are at the core of this issue.

“Children play carelessly, unaware of the toxic waste that may be under their front yard, while their…” Environmental Issues: Essential Primary Sources, edited by Brenda Wilmoth Lerner and K. Lee Lerner, Gale, 2006. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/PC3456487109/OVIC?u=nash87800&xid=c251ed8c. Accessed 25 Sept. 2017.

Context

The environmental health movement began in 1978 during the Love Canal Tragedy. This movement has been very influential in the past decades based on the legislation that has been passed. “Unlike most environmentalist, who emphasize the natural world, the environmental health movement shines a spotlight on human health and well-being” (Davies 1). This subtle difference influences how environmental issues are framed and how the public understands them. Therefore, the focus on human health has allowed this movement to capture the attention of the federal government and enact legislation. Significant environmental laws have been passed since the Love Canal Tragedy as a result of this movement. Superfund, also known as at the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, was created as a direct response to the Love Canal Tragedy. This provides a designated sum of money to contaminated waste sites in the country (Gibbs). As a result of this, hundreds of communities have been cleaned up and dumps have been converted to businesses. The use of chemicals by major corporations has been significantly reduced “as a direct result of the movement’s collaborative work to raise the cost of burying hazardous waste” (Gibbs). In fact, the commercial landfilling of toxic and hazardous waste has dramatically decreased because most commercial landfills have been closed (Gibbs). As a result, companies have to ship their wastes longer distances which contributes to increasing costs. Now, waste reduction and chemical substitution are more common in industry (Gibbs).

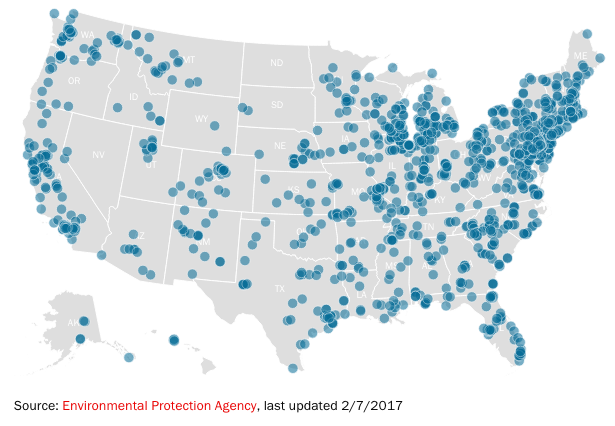

This image shows the Superfund sites throughout the nation. These 1,317 sites contain the worst of the toxic sites in the U.S. where toxic chemicals were dumped from factories for decades (Johnson).

Overtime, the movement’s focus on environmental justice and human rights did not go unnoticed. In 1994, Bill Clinton signed an Executive Order on Environmental Justice which focuses on racial disparities and the environment. The order “provides guidance for federal and state agencies to examine whether these communities or low-income areas are being deliberately targeted by polluting industries over alternative sites” (Gibbs 11). In addition to this, the order calls state governments to examine whether communities of color or low-income communities experience a different cleanup process than other communities. Overall, the environmental health movement has accomplished a great deal in legislative aspects, but also in the way people view the relationship between human rights, health, and environmental justice.

Politics of Health

The Love Canal Tragedy is related to politics of health because it portrays the interactions between the community and institutions (local, state, and federal governments) on the basis of health and justice. As shown by the numerous amounts of new legislation after the Love Canal Tragedy, new questions about the relationship between policy, taxes, regulations, and environmentalism came to the forefront. Love Canal residents became more and more involved in the fight for environmental justice. The history of Love Canal shows the public’s belief that a safe environment is a right and how the public may respond if this is not acknowledged. Informed consent is a term that refers to an individual who grants permission with complete awareness of the possible consequences. Included in the Superfund Amendment and Reauthorization Act, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act was created by movement leaders. This law “gives everyone the right to know what chemicals are being stored, transported, and disposed of at facilities and plants in a community” (Gibbs 9). In fact, hundreds of garbage incinerators have not been built, or have been closed, “either because they could not meet new and stronger regulations of because citizens blocked their construction” (Gibbs 9). The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act finally provides residents with crucial information and the ability to make choices for their health and well being.

The Love Canal Tragedy also created biological citizenship among Love Canal residents. Biological citizenship is fundamentally about recognition of the state and refers to the privileges that may be gained as a result of having certain biological characteristics on the basis of injury, a shared genetic status, or disease state (Mulligan). Once the dangers of the chemical toxins became apparent, residents demanded action from the state to issue an evacuation to all, not just protected populations like women and children. Pregnant women and children are considered protected populations because they are more vulnerable to toxic chemicals. For example, rapid brain development in fetuses and children make them more susceptible to chemicals that may impair brain function (Gibbs). In response to the strong opposition against only protecting protected populations, the state recognized these residents as biological citizens of the Love Canal neighborhood and an evacuation was issued. In the years following the tragedy, 1,300 residents of Love Canal also received a $20,000,000 settlement of their claims. (Britannica). Lastly, the recognition that came along with the Love Canal Tragedy also provided residents, like Lois Gibbs, a platform to raise awareness in the Environmentalist Movement.

Works Cited

“Children play carelessly, unaware of the toxic waste that may be under their front yard, while their…” Environmental Issues: Essential Primary Sources, edited by Brenda Wilmoth Lerner and K. Lee Lerner, Gale, 2006. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/PC3456487109/OVIC?u=nash87800&xid=c251ed8c. Accessed 25 Sept. 2017.

Davies, Kate. “Environmental Health: A Social Movement Whose Time Has Come.” Center for Health, Environment & Justice, Chej, 4 Apr. 2016, chej.org/2013/04/27/environmental- health-a-social-movement-whose-time-has-come/. Accessed 23 Sept. 2017.

Fowlkes, Martha R., and Patricia Y. Miller. “Chemicals and Community at Love Canal.” SpringerLink, Springer, Dordrecht, 1 Jan. 1987,link.springer.com/chapter/ 10.1007/978-94-009-3395-8_3#citeas. Accessed 23 Sept. 2017.

Gibbs, Lois Marie. Love Canal : And the Birth of the Environmental Health Movement. vol. Updated ed., 2011 ed, Island Press, 2011. EBSCOhost, proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/ login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx? direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=353473&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Johnson, David. “Superfund Sites: 1,317 US Spots Where Toxic Waste Was Dumped.” Time,Time, 22 Mar. 2017, time.com/4695109/superfund-sites-toxic-waste-locations/. Accessed 15 Oct. 2017.

“Land Pollution.” Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 10 Feb. 2015. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/land-pollution/474195. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

“Love Canal.” Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 8 Feb. 1999. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Love-Canal/49119. Accessed 19 Sept. 2017.

“Love Canal, New York.” Federal Agency Profiles for Students, edited by Kelle S. Sisung, Gale,1999. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/EJ2210023583/OVIC?u=nash87800&xid=64b1c218. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Mulligan, Jessica. “Obo.” Biological Citizenship – Anthropology , Oxford Bibliographies, 23 Sept. 2017, www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0164.xml.

Paigen, Beverly. “Controversy at Love Canal.” The Hastings Center Report, vol. 12, no. 3, 1982, pp. 29–37. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3561826. Accessed 19 Sept. 2017.

Thomson, Jennifer. “Toxic Residents: Health and Citizenship at Love Canal.” Journal of Social History, Oxford University Press, 3 Oct. 2016, muse.jhu.edu/article/631852/pdf. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Worthley, John A., and Richard Torkelson. “Managing the Toxic Waste Problem.” Managing the Toxic Waste ProblemAdministration &Amp; Society – John A. Worthley, Richard Torkelson, 1981, Sage Publications, Aug. 1981, journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/009539978101300202. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

« Back to Glossary Index