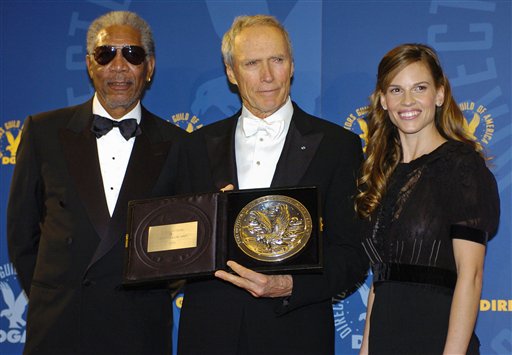

Actor and director Clint Eastwood, center, holds his nominees’ plaque for outstanding directorial achievement in feature film for his work in “Million Dollar Baby,” with cast members from the film Morgan Freeman, left, and Hilary Swank at the 57th Annual Directors Guild Awards in Beverly Hills, Calif., Saturday, Jan. 29, 2005. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello)

Background

Million Dollar Baby (MDB) is a film released in 2005 about the story of a young woman boxer named Margret Fitzgerald. It was directed and produced by Clint Eastwood (Waxman 2005). MDB won four Oscars, two Golden Globes, and two Screen Actors Guild Awards (IMDb 2017. Actors such as Morgan Freeman, Hilary Swank, and Clint Eastwood himself starred in the film. Although popular among movie critics, the film generated much controversy due to its portrayal of disability and euthanasia (Waxman 2005). The film depicted the boxer as a quadriplegic. Quadriplegia, which is also referred to tetraplegia, is usually the result of a spinal cord injury (SCI) and involves the paralysis of all four limbs to a certain degree (Colman 2015). In tetraplegics, injury occurs at the cervical level of the spinal cord. An estimated 282,000 people in the United States have a spinal cord injury (NSCISC 2016). Of these, an estimated 13.3%, or 37,506 people, have complete tetraplegia (NSCISC 2016). Mortality risk for those with spinal cord injuries increases with the level and severity of the injury and is more than double that of the population without a spinal cord injury(WHO). The WHO reports that “an estimated 20-30% of people with spinal cord injury show clinically signs of depression” (WHO 2013). Additionally, those with spinal cord injuries are at a higher risk for conditions such as urinary tract infections, pressure ulcers, and respiratory complications (WHO 2013). Nevertheless, the WHO reports that many difficulties that people with spinal cord injury face do not actually come from the spinal cord injury itself but instead stem from inadequate care and rehabilitation and “barriers in the physical, social, and policy environments” (WHO 2013). Euthanasia is when a person’s life is taken to end his or her suffering through voluntary or involuntary means (Martin 2015). During voluntary euthanasia, a person asks to have his or her life ended by someone else (Martin 2015). In involuntary euthanasia, those in positions of authority end the lives of those who cannot or have not given their consent (2015). The concept of assisted suicide is similar to that of euthanasia. Assisted suicide is assisting someone commit suicide by giving them the means necessary to do so (Martin 2015). When a patient decides to forgo life-preserving care, it is not considered a form of assisted suicide (Martin 2015).

Plot Summary

The film focuses on the boxing career of Margret Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank) and her aging trainer Frankie Dunn (Clint Eastwood). Frankie owns Hit Pit, the boxing gym run by Scrap (Morgan Freeman). Although Frankie initially refuses to train Maggie on the basis that he does not train women and that she is too old to begin a boxing career, he eventually accepts training her after they have a deep conversation on Maggie’s birthday. She reveals her humble beginnings in Missouri, how she escaped those circumstances, her feelings of never moving forward in her life, and how tired she is of waitressing. Boxing is the dream she held onto in a life that has not offered her much. Frankie feels empathy for her and takes her on as her coach. (Eastwood 2005)

Maggie unexpectedly fights her way up through the women’s boxing division ranks until Frankie receives an offer for her to fight in a high stakes fight. At that point Frankie gives Maggie a nickname, the Gaelic phrase “mo cuishle”, and Maggie soon becomes an immensely popular female boxer. With the winnings from her fights, Maggie buys a home for her mother. Her mother actually resents Maggie for the house, afraid that she will stop receiving welfare checks from the government, and tells her that everybody is making fun of her for boxing. This part of the film intentionally shows the separation between Maggie and her family to emphasize that Frankie and boxing are the only meaningful parts of her life. Foreshadowing a later part of the film, Maggie then tells Frankie a story about her father, the only person who cared about her, who had died of cancer. The story tells how her father put the family dog who had broken back legs to down. (Eastwood 2005)

Finally, Frankie arranges a title fight for Maggie against the women’s welterweight champion of the world. While the referee is not looking during the fight which Maggie dominates, her opponent punches and causes her to fall on top of a stool. The impact severely breaks Maggie’s neck. The break in her neck paralyzes her, making her a quadriplegic who cannot breathe without the assistance of a ventilator. Frankie desperately tries to find a doctor who will perform surgery on her, but every doctor he calls tells him that surgery would be useless. Bedridden, Maggie develops bedsores which leads to the amputation of one of her legs. When Maggie’s family comes to visit her, Maggie realizes they are just after her money and sends them away. Stuck in bed, unable to do what she loves, Maggie becomes depressed. She refuses Frankie’s offer to send her to college. Eventually, she asks Frankie to put her out of her misery like what her father did with the family dog. She tells Frankie that she wants to die before she can forget how famous she was. He refuses, horrified, and goes home. Later that night, Frankie receives a call from the hospital; Maggie attempted to commit suicide by biting off her tongue. The graphic scene of nurses and doctors stopping the blood emphasizes how desperate Maggie is to die. They keep her sedated from that point forward. After witnessing to what lengths Maggie will go to die, Frankie is torn about what to do. He consults his priest who tells him that if he kills Maggie he will never recover from it. Frankie also talks to Scrap who tells him that Maggie would die happier than many people who have not been able to achieve their dreams. Frankie, now convinced keeping her alive is a greater sin than helping her pass away, sneaks into the hospital to help her die. While she is sedated and halfway unconscious, he explains to her that the Gaelic name he gave her means “my darling” and “my blood” and explains to her what he is about to do. He removes her breathing tube and injects adrenaline into her IV. Frankie disappears after that, and Scrap narrates the rest of the story whose entire plot the audience finds out was actually a letter he wrote to Frankie’s estranged daughter about Frankie. (Eastwood 2005)

Criticism

After being released, Million Dollar Baby generated much controversy. In an article in the New York Times, the New York Times Hollywood reporter, Sharon Waxmon, captured the thoughts of some who defended the film. Supporters believe that filmmakers have the right to tell every story they choose however they want. They assert Clint Eastwood did not intend to make the film a political statement. Eastwood himself said that the film’s focus was not assisted suicide. Instead, he explained the “film is supposed to make you think about the precariousness of life and how we handle it” (Waxman 2005). In support of the film, the famous critic Roger Ebert wrote that “characters in movies do not always do what we would do…that is their right. It is our right to disagree with them” (Waxmon 2005).

However, critics of the film beg to differ. The director of the National Spinal Cord Injury Association voiced her concerns saying “any movie that sends a message that having a spinal cord injury is a fate worse than death is a movie that concerns us tremendously” (Waxmon 2005). A research analyst for the disability activist organization Not Dead Yet, Stephen Drake wrote, “This movie is a corny melodramatic assault on people with disabilities” (Waxmon 2005). Additionally, the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF) stated that the film was deeply offensive and centered on the assumption that “the quality of life of individuals with disabilities is unquestionably not worth living” (DREDF 2005). The DREDF stated that research shows that disabled people view their lives as normal and are just as satisfied with life as nondisabled people (DREDF 2005). Professor Lennard Davis at the University of Illinois points to the inaccuracies of the film as his criticism. He explains that Maggie could have chosen to die herself without Frankie’s help. Patients can refuse treatment under protection of the law since 1990 (Davis 2005). This refers to the 1990 case of Cruzan v Director, Missouri Department of Health. During this case, the United States Supreme Court decided that an informed, competent person has the right to refuse life sustaining medical care (Gaudin 1991:1320). Thus, instead of Frankie killing her dramatically and painfully with a shot of adrenalin, Maggie could have simply asked to be disconnected from her ventilator. The doctors would have then administered a sedative so that she could peacefully die (Davis 2005). Davis also points out that Maggie would not have not lost her leg in a high-quality rehab care facility because she would not have gotten bed sores with proper nursing. Furthermore, if in the unlikely case she did develop bed sores, Maggie would not have developed them as quickly as portrayed in the movie (Davis 2005). Critically, he claims that the director, Clint Eastwood, was not interested in accurately portraying disability (Davis 2005). He says instead that Eastwood, “like other normal filmmakers who make movies about the disabled, they are dealing in the grand myths and legends that surround the idea of disability rather than the reality of living with a disability” (Davis 2005).

An examination of Clint Eastwood’s past creates some doubt on his disinterestedness in disability. Eastwood owns a hotel in California. One of his disabled hotel guests sued Eastwood on the grounds that not only were the hotel restrooms not accessible for those with disabilities but the hotel rooms that were accessible cost much more than regular room (Davis 2005). While the court ruling dismissed many of the claims and only cited Eastwood for a few violations, Eastwood said that he does not approve of people suing small businesses to get money (Gaura and Gathright 2000). Eastwood lobbied in Congress to against the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). He fought for a bill which would require a 90-day notification of ADA violations that would allow business to fix violations before being taken to court (Davis 2005) (Gaura and Gathright 2000). Critics of the proposal said it would end in less legal challenges being made to disability barriers that make it difficult for disabled people to function in their everyday lives (Gaura and Gathright 2000)

Perspectives on Assisted Suicide in the Field of Disability

Assisted suicide is a source of internal and external conflict for disability rights activists. In the article, “Assisted suicide laws create discriminatory double standard for who gets suicide prevention and who gets suicide assistance: Not Dead Yet Responds to Autonomy, Inc.”, Diane Coleman highlights the issues of this conflict by discussing the appeal and response of disability activist groups to the assisted suicide case, Baxter v. State of Montana. She discusses the disability rights organization called Not Dead Yet challenges to two claims made by pro-assisted- suicide disability groups, such as Autonomy Inc. The claims are that assisted suicide is for those who are terminally ill, or physicians predict will die within 6 months, and can only be voluntary chosen by people deemed competent (Coleman 2010)

However, Not Dead Yet finds several problems with the assertion that assisted suicide is only carried out for terminally ill patients. They claim that instead of issuing legal prescriptions for the terminally ill, doctors frequently issue lethal prescriptions for a patient’s loss of autonomy, dignity, and feelings of being a burden (Coleman 2010). Not Dead Yet disagrees with doctors that needing help to carry out daily tasks equates a loss of dignity (Coleman 2010). The organization points to the mediatized portrayals of disability as presenting newly disabled people with death as the only option (Coleman 2010). Determining who is terminally ill became because more difficult as people many times outlive the predictions of their physicians. The analysis of reports from Oregon where assisted suicide is legal found that at least one person each year from 1999 to 2008 at least one person who requested assisted suicide lived significantly longer than 6 months after making their request (Coleman 2010). Evidently, these people were not terminally ill.

However, Not Dead Yet’s main point is that legalized assisted suicide creates a double standard in how an individual’s suicidal desire is responded to (Coleman 2010). The response depends on the individuals deemed health status. People who are incurably disabled or terminally ill get suicide assistance while the nondisabled get suicide prevention (Coleman 2010). They state that instead of a disability condition diminishing life “surrounding barriers and prejudices do so” (Coleman 2010). They say this violates the Americans With Disabilities Act(ADA) because governmental groups enforce suicide laws and healthcare providers respond to patients’ suicidal desires on the “presence or absence of disability” (Coleman 2010). Such discrimination is precisely what the ADA was created to address. Pro-assisted suicides also cite an ADA violation in assisted suicide laws for an entirely different reason. They take issue with the fact that lethal drugs must be self-administered (Coleman 2010). Some people who are physically impaired could not take the drugs on their own and thus could not choose to commit suicide.

Not Dead Yet also takes issue with the lack of protection against coercion by family members. They suggest family members’ financial concerns may influence their decisions (Coleman 2010). Pro-suicide disability groups counteract this argument by saying that such thinking is paternalistic because it assumes disabled patients cannot decide to end their life of their own clear- thinking volition and assert the laws have protections to prevent such coercion (Coleman 2010). Moreover, Not Dead Yet highlights that physicians may also coerce patients. Physicians have an incentive not to offer extended health care because they can be penalized for its costs to their practice (Coleman 2010). Shockingly, in some cases, physicians do not even need the consent of the patient or their family to withdraw treatment (Coleman 2010). This is because of something called futile care policies (Coleman 2010). Futile care policies refer to physicians deciding that interventions are unlikely to significantly benefit the patient (Jecker 2014). When a physician decides that treatment is futile because they the quality of life a patient will have post-treatment as too low, physicians can “overrule a patient or their authorized decision-maker in denying wanted life-sustaining treatment” (Coleman 2010).

How Million Dollar Baby Relates To Politics of Health

Million Dollar Baby relates to politics of health because it relates to the concepts of stigmatized representations, normalcy and disability, and structural violence. As discussed previously, most filmmakers are not interested in representing the true struggles of those with disabilities (2005). Since representations movies are the only views into the lives of the disabled for many people, accurate depictions of their lives prove particularly important. When Million Dollar Baby portrayed the life of Maggie post-injury, Eastwood showed Maggie choose death as preferable to her existence as a quadriplegic. Mediatized representations such as this influence people’s views on disability and assisted suicide. As discussed earlier, for those who are newly disabled, the portrayals may make death seem like their only viable option (Coleman 2010). Additionally, for the 37,506 quadriplegics in the United States, the film let them know their lives were worth nothing in the eyes of many (NSCISC 2016).

The film also heavily relied on the concepts of normalcy and disability. Maggie’s status as a women’s boxer was deemed “normal” while her life as a quadriplegic was deemed “abnormal” making her disabled. This reveals our societies association of a normal body with the ability to work and be independent. Without any physical impairments, Maggie could seemingly tackle any challenge through her own hard work. After her accident, she needed help to simply breathe. Thus, the state of her normality depended on her ability to be independent. The loss of this independence drove her to seek death as preferable to life as someone disabled.

Finally, Million Dollar Baby clearly highlights the structural violence in the United States against people with disabilities. Although Maggie was suicidal, she was not treated for depression. Her story exemplifies the systemic disparity in treatment for people with disabilities that has long existed in the US healthcare system. Her lack of treatment shows that people who are permanently disabled who are unhappy with life are presented with the choice of suicide instead of treatment (Coleman 2010). In contrast, people without disabilities are carefully treated for depression and are kept from dying at all costs. Clearly, the healthcare system chooses those who are worth saving, and people with disabilities do not fit the description. Furthermore, the legally protected power of physicians to withhold care without the consent of their patients or their families exemplifies systemic targeting of those with disabilities. The doctor can make quality of life judgments without factoring a patient’s perceived quality of life level. Perceiving a low quality of life for those with disabilities, physicians are more likely to decide a disabled patient less worthy of treatment than a nondisabled patient (Coleman 2010). In conclusion, Million Dollar Baby captures important controversial challanges facing the disabled community.

Bibliography

Coleman, Diane. “Assisted suicide laws create discriminatory double standard for who gets

suicide prevention and who gets suicide assistance: Not Dead Yet Responds to Autonomy, Inc.” Disability and Health Journal 3, no. 1 (2010): 39-50. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.09.004.

Colman, Andrew M. “quadriplegia.” In A Dictionary of Psychology. : Oxford University Press, 2015.

Davis, Lennard J. “Why ‘Million Dollar Baby’ infuriates the disabled.” Tribunedigital-

chicagotribune. February 02, 2005. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2005-02-02/features/0502020017_1_mission-ranch-inn-disability-film.

“Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund | Million Dollar Baby Built on Prejudice about

People with Disabilities.” Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund | Million Dollar Baby Built on Prejudice about People with Disabilities. February 2005. https://dredf.org/archives/mdb.shtml.

Eastwood, Clint, Hilary Swank, Morgan Freeman, Albert S. Ruddy, Tom Rosenberg, Paul

Haggis, and F. X. Toole. 2005. Million dollar baby. Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video.

Gaudin, Anne Marie. “Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health: To Die or Not to Die:

that is the Question-But Who Decides?”, 51 La. I,, Rev. (1991), http://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol51/iss6/7

Jecker, Nancy. “Medical Futility.” Futility: Ethical Topic in Medicine. March 14, 2014.

https://depts.washington.edu/bioethx/topics/futil.html.

Maria Alicia Gaura, Alan Gathright, Chronicle Staff Writers. “Eastwood Wins Suit Over ADA /

But jury says resort needs improvements.” SFGate. September 30, 2000. http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Eastwood-Wins-Suit-Over-ADA-But-jury-says-2736250.php.

Martin, Elizabeth. “assisted suicide.” In Concise Medical Dictionary. : Oxford University Press,

- http://www.oxfordreference.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199687817.001.0001/acref-9780199687817-e-11146.

“Million Dollar Baby (2004).” IMDb. Accessed March 30, 2017.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0405159/.

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, Facts and Figures at a Glance. Birmingham, AL:

University of Alabama at Birmingham, 2016. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/Facts%202016.pdf

Norden, Martin F. “Million Dollar Baby.” In Encyclopedia of American Disability History,

edited by Susan Burch, 618. Facts on File Library of American History. New York: Facts on File, 2009. Gale Virtual Reference Library. http://go.galegroup.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=nash87800&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX1698300480&sid=exlibris&asid=566abc080be43f03790445132fa1d9b1.

“Spinal cord injury.” World Health Organization. November 2013.

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs384/en/.

« Back to Glossary Index