Definition and Background

Oxycodone is a semisynthetic drug with strong pain-relieving effects. Oxycodone’s manufacture, prescription, and distribution are federally regulated, and its trafficking is punishable by law in several countries including the U.S., the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Germany (Rogers, 2018). In 1916, oxycodone was produced from the alkaloid thebaine, which is naturally found in the opium poppy. The following year of 1917, oxycodone was first introduced into clinical practice in Germany to be used for the treatment of acute pain (Kalso, 2005). Oxycodone’s anesthetic quality is a result of its ability to bind to and stimulate the central nervous system’s opioid receptors. This process “inhibits the neural relay of pain signals from affected parts of the body”, enabling a user to feel less pain (Rogers, p. 1) In addition, oxycodone activates reward pathways in the brain, which “elicits psychological responses such as euphoria” (Rogers, p. 1).

Oxycodone is primarily used for treating cancer-related pain, acute postoperative pain such as childbirth, and chronic pain problems such as injuries, bursitis, dislocations, neuralgia, arthritis, and lower back pain (Kalso, 2005). Extended use of oxycodone desensitizes opioid receptors, which causes users to develop resistance to its effects (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004). As a result, long-time users must increase drug dosage in order to attain the same level of pain relief as before (Rogers, 2018). When extended users stop taking oxycodone, they often experience withdrawal symptoms such as “restlessness, muscle and bone pain, insomnia, diarrhea, vomiting, cold flashes, and involuntary leg movements” (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004). If taken in excessive amounts, oxycodone can trigger severe respiratory depression that can result in death (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004). Because of its mechanisms that induce dependence and tolerance in a user, oxycodone is extremely addictive and consequently has high potential for abuse (Ordóñez, González, & Espinosa, 2007).

Presently, oxycodone is marketed as a prescription pain medication through several brand names including OxyContin, Percolone, and Oxyfast (Rogers, 2018). OxyContin contains oxycodone hydrochloride and is available in controlled-release tablets of 10, 20, 40, and 80 milligrams. Oxycodone is also sold in combination with other substances such as acetaminophen. Percocet, a frequently prescribed medication for moderate pain, contains both oxycodone and acetaminophen. For the purposes of this paper, I will focus on OxyContin, which is the form of oxycodone that is widely abused for its “heroin-like effects” (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004).

Historical Context

OxyContin is a controlled-release form of oxycodone that was developed and produced by pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma. OxyContin was approved by the FDA in December 1995, and was designated a Schedule II substance under the Controlled Substances Act (Griffin & Spillane, 2013). According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, drugs are classified into five distinct schedules or categories depending on the drug’s “acceptable medical use and abuse or dependency potential”, with the abuse rate being the crucial determining factor in the drug’s scheduling. Substances deemed as Schedule II are defined as drugs with “a high potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence, and are also considered dangerous” (U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration). OxyContin was created with the goal of reducing the frequency of intake as well as lowering the severe side effects experienced by patients prescribed oxycodone (Rogers, 2018). OxyContin is unique from other forms of oxycodone in that its extended release system that gives a user up to 12 hours of pain relief. OxyContin contains a high amount of oxycodone, but dissolves slowly as it passes through the digestive system, resulting in a “gradual and sustained drug release” (Rogers, 2018). Purdue marketed OxyContin as a “minimally addictive opioid pain reliever appropriate for long-term use in chronic pain” (Hansen & Skinner, 167). Thus, OxyContin became the first opioid to seemingly bypass the problem of addiction while maintaining its anesthetic qualities (Hansen & Skinner, 2012). The standard OxyContin pills (shown in Figure 1) are not harmful when taken in their intact form. However, when crushed, OxyContin can yield vast quantities of oxycodone that can be “snorted, injected, or swallowed to produce a powerful high” (Rogers, 2018).

Figure 1: OxyContin pills arranged at pharmacy in Montpelier, VT (AP Photo/Toby Talbot)

OxyContin sales were quite successful when OxyContin was introduced to the U.S. pharmaceutical market, and “experienced steady and impressive levels of growth” (Griffin & Spillane, p. 164). In 1999, reports of OxyContin abuse and diversion began to attract national attention and causes for concern among law enforcement and public health agencies. Drug diversion is defined as the “unlawful channeling of drugs from legal sources to the illicit marketplace (Cicero, Kurtz, Surratt, Ibanez, & Ellis, p. 284). The diversion of OxyContin and its subsequent abuse is frequently achieved by “illegally written or forged prescriptions, theft, and ‘doctor shopping’ which is when individuals who may or may not have a legitimate ailment visit numerous doctors to obtain drugs in excess of what should be prescribed legitimately” (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004).

Over the past 15 years, copious national surveys, prescription drug abuse surveillance programs, and federal monitoring systems have recorded a considerable increase in the abuse of prescription opioids. According to Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) data, the number of emergency department mentions for oxycodone rose from 10,825 to 22,397 from 2000 to 2002 (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004). Moreover, according to the National Drug Threat Survey 2003 (NDTS) data, 67% of state and local enforcement agencies state that OxyContin is “commonly diverted and abused in their areas, a higher percentage than any other pharmaceutical drug” (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004). Out of these agencies, a higher percentage in the Southeast region report that OxyContin is diverted and abused in comparison to those in the Northeast/Mid-Atlantic, Great Lakes, West Central, Pacific, and Southwest regions (refer to Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Regions in America (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004)

OxyContin’s abuse is more prominent in rural areas in comparison to large metropolitan areas, particularly in Maine, West Virginia, and Appalachian Kentucky (Leukefeld, Walker, Havens, Leedham, & Tolbert, 2007). Researchers believe that the greater prevalence of OxyContin abuse in rural areas is the result of a combination of large economic, environmental, and social factors that put rural Americans more at risk. University of California-Davis epidemiologist Magdalena Cerda says that the specific types of jobs common in rural areas such as “manufacturing, farming, and mining tend to have higher injury rates…lead[ing] to more pain, and possibly, to more painkillers” (Runyon, 2017). Consequently, this economic stressor creates vulnerability to the general use of OxyContin, producing greater numbers of opioid prescriptions, which inevitably “creates availability from which illegal markets can rise” (Keyes et al., p. 52). Additionally, Kirk Dombroski, a sociologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, says that people who live in rural areas “tend to have sprawling social networks” that can further facilitate drug diversion and distribution by giving rural inhabitants more connections and opportunities for drug access (Runyon, 2017). According to the DEA (2002), a treatment program in rural Appalachia reported that 41% of its treatment admissions in the first six months of 2001 were related to OxyContin. From 1998 to 2000, the number of Kentucky statewide treatment admissions for oxycodone increased by 163% with high rates of OxyContin-related crimes (Leukefeld et al., 2007).

As an impact of the widespread media coverage of OxyContin’s abuse and ensuing overdose deaths, doctors have become increasingly cautious of prescribing OxyContin (Cicero, Kurtz, Sarratt, Ibanez, & Ellis, 2011). Likewise, insurance companies have become more and more unwilling to pay for OxyContin, an “expensive brand name with no currently available generic (Cicero et al., p. 298). Consequently, OxyContin is attained more commonly through dealers as a “street drug” (Cicero et al., p. 298).

Perspectives and Controversies

There have been numerous factors identified with the abuse of OxyContin. The most significant was the ability of users to manipulate OxyContin and obtain the full dose of oxycodone through the very simple means of crushing the controlled-release tablet (Griffin & Spillane, 2013). The controversy that lies here is that Purdue Pharma was apparently aware of this “vulnerability” while OxyContin was in the process of being approved by the FDA (Griffin & Spillane, p. 167). According to Purdue Pharma lab tests, “crushing a capsule of OxyContin would allow a would-be recreational user to immediately receive up to 68% of the oxycodone contained” in it (Griffin & Spillane, p. 167). The product information itself advertised its potential for abuse by “[advising] patients not to crush or dissolve the tablets because this released a large dose of the drug” (Degenhardt, Larance, Bruno, Lintzeris, & Ali, p. 227). While there is general agreement that OxyContin was structurally flawed by making it “too easy for nonmedical users to manipulate” and that Purdue made OxyContin “too vulnerable to a certain segment of consumers”, several accounts accuse Purdue with “acting inappropriately to increase consumer demand” (Griffin & Spillane, p. 168).

Specifically, Purdue was accused of facilitating the abuse and diversion of OxyContin through its ostentatious campaign for the drug. In 2001 alone, Purdue Pharma spent $200 million on OxyContin advertising and promotions (Griffin & Spillane, 2013). Purdue targeted its advertising in medical journals and directly to medical physicians, and even held more than 40 national pain management and speaker-training conferences centered around OxyContin. Pharma is said to have “paid its sales representatives large bonuses as an incentive to increase OxyContin sales, and issued coupons entitling new patients to free samples at participating pharmacies” (Dhalla, Persaud, & Juurlink, 2011, pg. 570). A “call list of almost 100,000 physicians across the country” (Hansen & Skinner, p. 181) were “encouraged to prescribe it liberally by pain management specialists who participated in professional education programs funded by [Pharma Purdue]” (Degenhardt et al., p. 226). This spawned much suspicion that Purdue was promoting the use of OxyContin “beyond reasonable medical bounds” (Griffin & Spillane, p. 169).

The FDA sent 2 warning letters to Purdue Pharma regarding its advertisement for OxyContin. In 2007, Purdue Pharma pled guilty to a felony count of misbranding OxyContin, and acknowledged that “its employees misled physician about the risk of addiction” (Dhalla et al., 2011, pg. 570). Pharma agreed to pay “$470 million in fines to the federal government as well as $130 million to satisfy personal injury claims” (Griffin & Spillane, p. 169). The reaction to the court outcome was mixed, one side attacked the settle either for “undue leniency or for undue severity” (Griffin & Spillane, p. 169). However, it is worth noting that this sum in fines was “dwarfed by the $3 billion that Purdue gained in OxyContin profits in 2009 alone” (Hansen & Skinner, p. 182). According to a very recent NPR news article, Alabama filed a lawsuit in federal court against Purdue Pharma with the same recurring accusation that the company is “fueling the opioid epidemic by deceptively marketing” and “failing to accurately portray the risks and benefits” of the drug (Raphelson, 2018). It was not until 2010 that Purdue Pharma stopped sales of the original OxyContin and introduced an “abuse-resistant formulation” of OxyContin, one that would not be able to be crushed (Griffin & Spillane, p. 167).

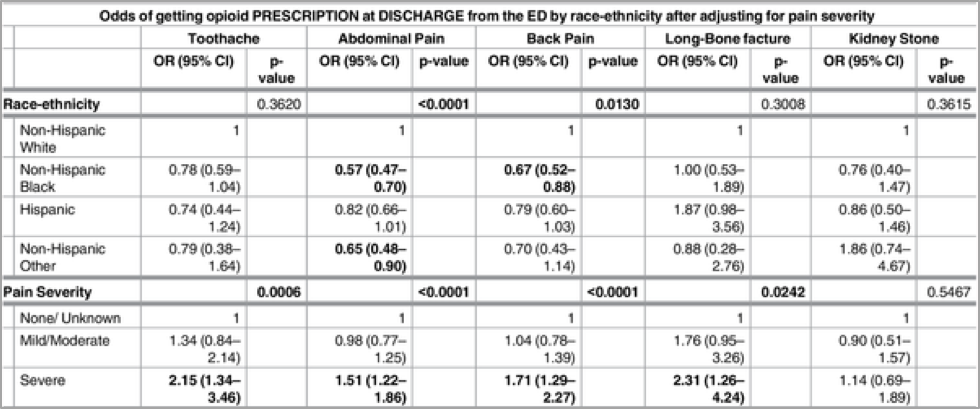

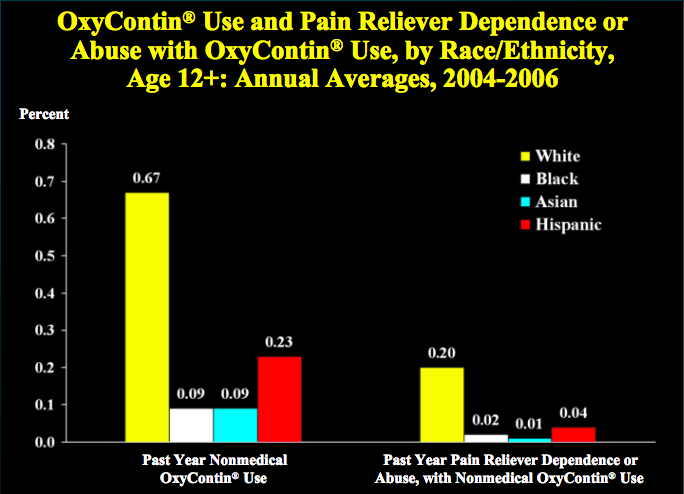

On the other hand, hospitals and physicians have attempted to curb the problem of opiate abuse by reducing the prescription of OxyContin to patients who appear to be “drug-seekers”. Certain “non-definitive conditions” such as back pain and abdominal pain have long been associated with drug-seeking behavior, because they do not have “visible clinical and/or diagnostic presentations” (Singhal et al., 2016). Hence, when emergency department physicians encounter patients who complain of pain, they often rely on subjective factors in order to promptly decide whether or not to prescribe a patient OxyContin. A research study discovered that the factor of race-ethnicity largely influences a physician’s decision to prescribe a patient OxyContin. The results revealed that there were substantial racial-ethnic disparities in OxyContin prescriptions for non-definitive conditions, with minorities being less likely to receive OxyContin. According to Singhal et al. (2016), non-Hispanic blacks had significantly lower odds of receiving OxyContin during their ED visits for back pain and abdominal pain as compared to non-Hispanic whites (see Fig. 3). This is intriguing when considered in the light of another study, which found that OxyContin abuse and addiction is actually higher among non-Hispanic whites, compared to Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks (see Fig. 4). According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), young white male adults are the most likely demographic to abuse OxyContin (National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.), 2004).

Figure 3: Odds of receiving opioid as prescription at discharge from ED by race-ethnicity (Singhal et al., 2016)

Figure 4: OxyContin Use and Pain Reliever Dependence or Abuse with OxyContin Use, by Race/Ethnicity (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008)

Relation to Politics of Health

Oxycodone has many connections to what we have learned in Politics of Health, especially in relation to the concepts of medicalization, pharmaceuticalisation, and racialization.

In Conrad’s “Shifting Engines of Medicalization”, he argues that biotechnology, consumers, and managed care drive medicalization now more than ever. He discusses how current medical care is motivated by commercial and market interests through “attempts at cost controls and corporatized medicine” (Conrad, p. 4). He states that “pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries are becoming major players in medicalization…they can now advertise directly to the public and create markets for their products” (Conrad, p. 5). In doing this, institutions compete for patients as their consumers. OxyContin demonstrates the biotechnology aspect of medicalization, in that Purdue Pharma as a pharmaceutical company made a tremendous effort to try to financially profit as much as it could through questionable advertising and promotion of the medication. In the drug business, pharmaceutical advertising can have many harmful effects in that it has a large hand in the over-prescription of medicine in the manipulation of consumer attitudes. This has implications in how the U.S. drug assessment liability system today needs modification to ensure that pharmaceutical companies that already make exorbitant amounts of money do not view penalties, such as the fine that Purdue easily paid off, as a minor cost of doing business.

In “The pharmaceuticalisation of society? A framework for analysis”, Williams describes a salient dimension of pharmaceuticalisation as “social identities that revolve around particular drugs, changing regulatory landscapes that affect access to drugs, and non-medical uses of medical drugs” (Williams et al., p. 714). The abuse of OxyContin is markedly impacted by its prevalence in rural regions that create the perfect storm of economic, environmental, and social factors for its diversion. This reflects the current “creation of social identities and the mobilization of consumer groups around drugs” that characterizes pharmaceuticalisation (Williams et al., p. 716).

OxyContin exemplifies the concept of racialization in medicine, when considering the prominent racial-ethnic disparities in its prescription for non-definitive conditions. These disparities are a reflection of healthcare providers’ inherent biases and leads to prejudiced treatment of patients based on race. Physicians are more likely to judge non-Hispanic black patients as a “drug-seeker” in comparison to a non-Hispanic white patient, even when presented with similar pain-related complaints from both patients. This can be connected to Mollow’s article “”When Black Women Start Going on Prozac…” The Politics of Race, Gender, and Emotional Distress in Meri Nana-Ama Danquah’s Willow Weep for Me”, in which Danquah discusses her struggle with facing racial barriers in receiving appropriate health care for depression. It is stated that “people of color, especially African Americans, are less likely to be diagnosed with depression or prescribed medication when they report their symptoms to a doctor; even in studies controlling for income level and health insurance status, the disparities are great” (Mollow, p. 286). Similar to illnesses such as depression, chronic pain does not have outwardly symptoms that would allow physicians to easily identify a patient’s need for medication. This is concerning because physicians’ denial towards the therapeutic needs of black patients can result in patients not receiving pain relief such as OxyContin when it is necessary. It can be said that racial prejudice has serious repercussions in the widening of existing health disparities, since minorities already experience greater socio-economic barriers in accessing health care.

References

Cicero, T. J., Kurtz, S. P., Surratt, H. L., Ibanez, G. E., & Ellis, M. S. (2011). Multiple Determinants of Specific Modes of Prescription Opioid Diversion. Journal of Drug Issues, 41(2), 283-304.

Conrad, P. (2005). The Shifting Engines of Medicalization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(1), 3-14. doi:10.1177/002214650504600102

Degenhardt, L., Larance, B., Bruno, R., Lintzeris, N., & Ali, R. (2015). Evaluating the potential impact of a reformulated version of oxycodone upon tampering, non-adherence and diversion of opioids: the National Opioid Medications Abuse Deterrence (NOMAD) study protocol. Addiction, 110(2), 226-237.

Dhalla, I. A., Persaud, N., & Juurlink, D. N. (2011). The prescription opioid crisis. British Medical Journal, 343(7823), 569-571.

Griffin, O. H., & Spillane, J. F. (2013). Pharmaceutical Regulation Failures and Changes: Lessons Learned From OxyContin Abuse and Diversion. Journal of Drug Issues, 43(2), 164-175.

Hansen, H., & Skinner, M. E. (2012). From White Bullets To Black Markets And Greened Medicine: The Neuroeconomics And Neuroracial Politics Of Opioid Pharmaceuticals. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 36(1), 167-182. doi:10.1111/j.2153-9588.2012.01098.x

Kalso, E. (2005, May). Oxycodone. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15907646

Leukefeld, C., Walker, R., Havens, J., Leedham, C. A., & Tolbert, V. (2007). What Does the Community Say: Key Informant Perceptions of Rural Prescription Drug Use. Journal of Drug Issues, 37(3), 503-524.

National Drug Intelligence Center (U.S.). (2004, August). OxyContin diversion, availability, and abuse. Retrieved from http://www.usdoj.gov/ndic/pubs10/10550/10550p.pdf

Ordóñez, A., González, M., & Espinosa, E. (2007, May). Oxycodone: a pharmacological and clinical review. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17525040

Raphelson, S. (2018, February 7). Alabama Targets OxyContin Maker Purdue Pharma In Opioid Suit. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/02/07/584034397/alabama-targets-oxycontin-maker-purdue-pharma-in-opioid-suit

Rogers, K. (2018). Oxycodone. Retrieved from http://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/oxycodone/488677

Additional Resources

Kalso, E. (2005). Oxycodone. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management,29(5), 47-56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.010

Keyes, K. M., Cerdá, M., Brady, J. E., Havens, J. R., & Galea, S. (2014). Understanding the Rural–Urban Differences in Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and Abuse in the United States. American Journal of Public Health,104(2), 52-59. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301709

Mollow, A. (2006). “When Black Women Start Going on Prozac…” The Politics of Race, Gender, and Emotional Distress in Meri Nana-Ama Danquah’s Willow Weep for Me. MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States,31(3), 67-99. doi:10.1093/melus/31.3.67

Runyon, L. (2017, January 4). Why Is the Opioid Epidemic Hitting Rural America Especially Hard?. NPR Illinois. Retrieved from http://nprillinois.org/post/why-opioid-epidemic-hitting-rural-america-especially-hard#stream

Singhal, A., Tien, Y., & Hsia, R. Y. (2016). Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Opioid Prescriptions at Emergency Department Visits for Conditions Commonly Associated with Prescription Drug Abuse. Plos One,11(8). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159224

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). Drug Scheduling. Retrieved March 03, 2018, from https://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml

Williams, S. J., Martin, P., & Gabe, J. (2011). The pharmaceuticalisation of society? A framework for analysis. Sociology of Health & Illness,33(5), 710-725. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01320.x

« Back to Glossary Index