Insurance is an idea implemented to mitigate catastrophic loss, either for an individual or group. The concept came about through merchants wanting to protect their investment in goods being shipped across the world on ships. In the 14th century, insurance began to separate from investment, allowing for the development of a new industry and a useful divergence of roles.[1] Insurance works by having groups or individual pay a certain amount on a regular basis (premiums), to then be covered against catastrophic loss. Modern insurance was introduced in Enlightenment-era England, where variations of insurance were issued depending on the good being insured. Property insurance, as we know it, stemmed from the Great Fire of London. After the fire in 1666, a number of property insurance offices attempted to set up shop, but ultimately folded. However, in 1681, the first fire insurance company was set up.[2] The specialization of insurance types further allowed the industry to grow and increase the utility of insurance.

A precursor to health insurance, life insurance also began in England during the 18th century. The first company to offer life insurance started in 1706. A few decades later, in 1762, the world’s first mutual insurer (where the company is entirely owned by policyholders) established age-based premiums that used mortality rates in their calculations of policies.[3] Calculating an individual’s risk-profile using their familial history of disease and other health risk factors became a cornerstone of health insurance.

Insurance works in that an individual will seek health insurance in order to prevent against any financially catastrophic operations in the unfortunate event they become ill. Aside from premiums, there are other forms of cost-sharing, such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance.[4] In the US, there are three major sources of insurance for a working-age individual. The first, which covers the vast majority of the US population who have health insurance coverage, is employer-sponsored insurance. Next, there is health coverage provided by the federal government through Medicare and Medicaid. This type of health coverage depends on an individual fitting into certain categories based on socio-economic status or other groups that have a recognized need for health coverage but may be incapable of affording it themselves. Finally, there are private, personal health plans that are generally more expensive than other group plans due to the higher risk of liability for the insurance company.

The first type of insurance stated above, employer-sponsored insurance, expanded greatly during World War II, as a result of tight wage controls. Companies were unable to offer higher wages to workers or other employees in order to attract them to certain positions. However, when the War Labor Board declared that fringe benefits, like sick leave and health insurance, did not count towards wage controls, they became a new tool for companies to utilize.[5] In order to attract employees, companies began to offer increasingly generous benefits in terms of sick leave and especially health insurance.[6] These fringe benefits were part of an employer’s expense, since they didn’t count towards wage controls. Therefore, employer-sponsored insurance existed in a gray area and was tax-exempt for companies. This allowed companies to offer increasingly generous health packages without increasing wages commensurately, enabling companies to get more value, dollar-for-dollar, out of their compensation for employees.[7]

Public health coverage took the form of Medicaid and Medicare, which were established in 1965. Medicare provided health insurance for individuals over the age of 65, and others with some form of permanent disability. Medicare traditionally requires high levels of cost-sharing in order to be utilized, however, approximately 90% of Medicare enrollees have some form of supplemental insurance to offset these high levels of cost-sharing.[8] Medicaid is meant to provide a form of health insurance to the very poor in the US. It is a joint federal and state program, where the state determines the eligibility requirements for Medicaid enrollees, and the federal government provides a certain percentage of matching funds to contribute towards the health coverage of Medicaid enrollees.[9] These eligibility requirements make enrollment for Medicaid categorical, where in order to be enrolled, an individual must fall into certain categories determined by law.[10]

Private insurance existed before the other types of insurance discussed, however, it was generally too expensive for the majority of individuals to afford. Most people were expected to pay for their treatments out of pocket on a fee-for-service model. As costs in the healthcare industry increased disproportionately to wages or health insurance benefits, many individuals became unable to afford modern medical treatments.[11]

There are two concepts that are typically associated with the increased cost of medical treatments, and by association, higher insurance rates. The first, likely the most easily understood, is the medical technology arms race.[12] In the past century, the costs linked to medical treatments have exponentially grown. These costs are a product of not only research and development costs incurred by pharmaceutical and other medical companies, but are due to the negligible benefits that are connected to marginally improving technologies. In the US, it is expected that hospitals and other treatment centers will have the newest or best equipment, otherwise patients will go elsewhere if they are financially capable. The cost of this medical technological arms race is then conferred on the patients as ever-increasing hospital bills. However, this bill is rarely ever fully paid out, due to the health insurance that a majority of patients have.[13]

This incidence then leads to a second concept associated with higher medical costs, moral hazard. In healthcare examples, moral hazard occurs because subjects are rarely faced with the full costs of treatment due to health insurance, and are therefore implicitly encouraged to overconsume medical treatment, even if there are marginal benefits.[14] Moral hazard also affects health care providers, because they know that consumers will most likely not be too financially affected by the cost of procedures and would want to be thoroughly examined, providers are more likely to overprescribe various examinations and procedures. All in all, these inherent functions of the current healthcare system lead to higher overall costs in the healthcare industry.[15]

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, commonly shortened to ACA or also known as Obamacare, was a two-fold measure to boost health insurance enrollment rates, while simultaneously lowering health care costs, passed in 2010 and went into effect in 2014.[16] The former goal was to be achieved by dramatically expanding Medicaid eligibility and overhauling the individual insurance market to make it more affordable, while maintaining the existing structure around Medicare, Medicaid, and employer-sponsored insurance markets.[17] The latter goal was meant to realized by lowering rates of compensation through Medicare and other cost-cutting measures. Even though the ACA required more spending by the federal government, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the federal deficit would decrease because of new taxes in addition to the cost-cutting measures.[18]

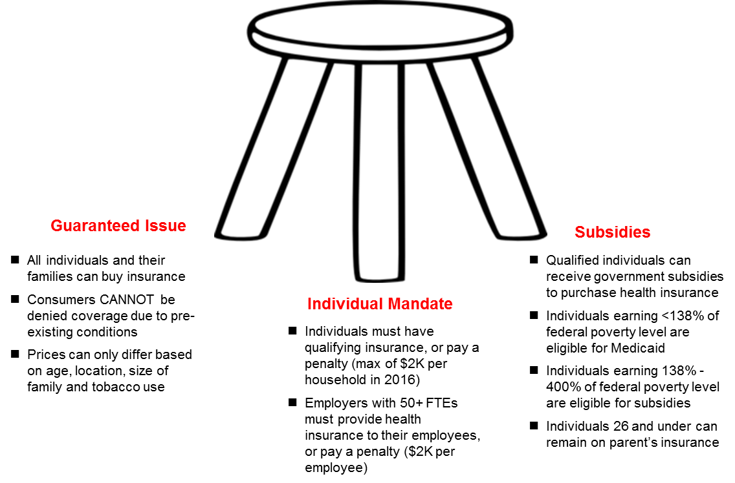

Figure 1. A visual depiction of the ACA’s provisions and intended effect[19]

The ACA attempted to achieve universal health care coverage through three main concepts, commonly visualized as a three-legged stool, as shown in Figure 1. The seat of the stool represents universal coverage, and the three legs are three provisions of the ACA intended to achieve the desired effect of universal coverage.[20] The first leg, guaranteed issue, is meant to ensure that all individuals or families will qualify to for private insurance plans, or qualify for Medicaid. This leg was created to counteract many insurance companies policy of the pre-existing condition exemption, which prevented many ill people from having affordable health insurance. The second leg, individual mandate, was an attempt to lower the liabilities of health insurance companies. Because insurance companies were now forced to provide insurance for everyone, the individual mandate was created to force young, healthy individuals to retain some form of health insurance, whereas they might have previously forgone this expense. By enlarging the enrollee pool from just those who are sick, to a mix of healthy and ill consumers, insurance companies wouldn’t be forced lose revenue. Finally, the third leg of the stool, subsidies, were created to guarantee that anyone who chose to have health insurance, would be able to afford it in some form. The three-legged stool is meant to demonstrate how the provisions of the ACA work in tandem, and if any one leg of the stool is weakened or removed, the entire system can fall apart.[21]

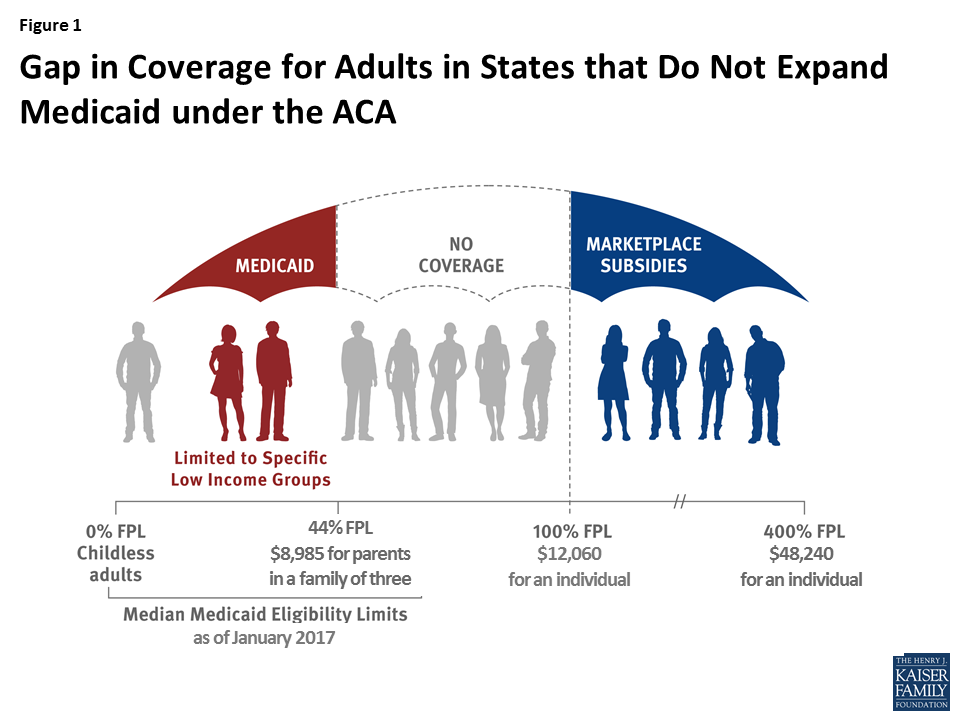

While in theory, the ACA seems to achieve a desirous goal of increasing health coverage across the US, while simultaneously lowering healthcare costs, this intended result has not been achieved.[22] Even though the ACA is based on a plan implement by a Republican governor in Massachusetts, conservatives bristled at a perceived overstepping of the federal government’s authority. When the ACA was first passed, this was demonstrated by some conservative states’ decision to not expand Medicaid in their states, which led to a coverage gap amongst the poor in those states. Figure 2 demonstrates how individuals, in states that did not expand Medicaid, were left without any form of coverage. Because the subsidies only effect those making the same or more as the federal poverty level (FPL), those who made less than the FPL and didn’t qualify for Medicare or Medicaid under other categories, were unable to qualify for other subsidies, such as tax credits or cost-sharing subsidies, and were left in the theoretical cold.

Figure 2. A visual depiction of those in Medicaid Coverage Gap[23]

Conservatives in the federal government attempted to repeal and replace the ACA many times since the law’s passage, but failed to construct a meaningfully improved alternative to the ACA.[24] Ultimately, conservatives were able to weaken Obamacare through a pseudo-repeal of the individual mandate. Instead of actually repealing this particular provision, conservatives removed the tax penalty for not having health insurance as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, effectively achieving the same result as a repeal of the individual mandate.[25]

At first glance, the relationship of health insurance to politics of health may be ambiguous. However, after diving past a shallow understanding of health insurance, the intricacies of health insurance in the US demonstrates many topics discussed in class. While looking at the minutiae of health insurance, there are themes of biological citizenship and biopower represented. While the concept of biological citizenship stems from the Chernobyl incident in the Ukraine, it can somewhat be translated to the situation of the impoverished in the US.[26] While those who may have some form of disability might have not been injured to the government’s negligence, the categories of Medicaid and Medicare still represent a form of biological citizenship because those categories were created through lobbying efforts from the affected groups. Because of the lobbying, only those who fall neatly into those aforementioned categories can qualify for state benefits.[27]

Biopower in health insurance can also be examined through a lens of the impoverished. The socio-economic inequities that permeate the US cause poor individuals to be unable to achieve good health. Those living in states that did not expand Medicaid, those living in the coverage gap, are explicitly forced to live with a lower quality of health due to the state’s decision.[28] However there is also a second occurrence of the loss of biopower. The implementation of the individual mandate also causes individuals to lose their say in the control of the health of their own body. This concern may be ancillary to those who attempt to fix the current healthcare, but it is a concern nonetheless. In general, the ACA seemed to have a desirous effect, but fell short due to political intervention, and the realities of the current healthcare system.

[1] Lucy, R. b. D. 2004. “James Franklin The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability before Pascal.” Law, Probability and Risk 3 (1): 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/lpr/3.1.87.

[2] Sutherland, L. S. 1962. Review of Review of The Sun Insurance Office 1710-1960. The History of Two and a Half Centuries of British Insurance, by P. M. G. Dickson. The Economic History Review 14 (3): 567–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/2591902.

[3] “Equitable Life.” n.d. Accessed April 14, 2018. http://www.equitable.co.uk/about-us/history-and-facts/.

[4] Scott Braithwaite, R., Cynthia Omokaro, Amy C. Justice, Kimberly Nucifora, and Mark S. Roberts. 2010. “Can Broader Diffusion of Value-Based Insurance Design Increase Benefits from US Health Care without Increasing Costs? Evidence from a Computer Simulation Model.” PLoS Medicine 7 (2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000234.

[5] Sep 22, Published:, and 2015. 2015. “2015 Employer Health Benefits Survey.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog). September 22, 2015. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2015-employer-health-benefits-survey/.

[6] Buchmueller, Thomas C., and Alan C. Monheit. 2009. “Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance and the Promise of Health Insurance Reform.” Inquiry 46 (2): 187–202.

[7] “How Does the Tax Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Work?” n.d. Tax Policy Center. Accessed April 14, 2018. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-does-tax-exclusion-employer-sponsored-health-insurance-work.

[8] Oct 30, Published:, and 2010. 2010. “Medicare Chartbook, 2010.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog). October 31, 2010. https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/medicare-chartbook-2010/.

[9] “Medicaid Home | Medicaid.Gov.” n.d. Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.medicaid.gov/index.html.

[10] “Annual Statistical Supplement, 2011 – Medicaid Program Description and Legislative History.” n.d. Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2011/medicaid.html.

[11] Artiga, Samantha, Jennifer Tolbert, Petry Ubri Published: Nov 09, and 2017. 2017. “How Do Health Care Costs Fit into Family Budgets? Snapshots from Medicaid Enrollees.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog). November 9, 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-do-health-care-costs-fit-into-family-budgets-snapshots-from-medicaid-enrollees/.

[12] “The Medical Arms Race.” n.d. The Incidental Economist (blog). Accessed April 14, 2018. https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/the-medical-arms-race/.

[13] Kessler, Daniel P., and Mark B. McClellan. 2000. “Is Hospital Competition Socially Wasteful?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (2): 577–615. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554863.

[14] Nyman, John A. 2004. “Is ‘Moral Hazard’ Inefficient? The Policy Implications Of A New Theory.” Health Affairs 23 (5): 194–99. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.194.

[15] Ross, Sean. 2015. “How Does the Affordable Care Act Affect Moral Hazard in the Health Insurance Industry?” Investopedia. April 30, 2015. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/043015/how-does-affordable-care-act-affect-moral-hazard-health-insurance-industry.asp.

[16] “Testimony on CBO’s Analysis of the Major Health Care Legislation Enacted in March 2010.” 2011. Congressional Budget Office. March 30, 2011. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/22077.

[17] “Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: 2016 to 2026.” 2016. Congressional Budget Office. March 24, 2016. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51385.

[18] “Health Insurance Coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010 – 2016.” 2016. ASPE. March 2, 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-and-affordable-care-act-2010-2016.

[19] “Here’s What You Need To Know About The Affordable Care Act.” n.d. Mahesh VC. Accessed April 14, 2018. http://www.mahesh-vc.com/blog/heres-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-affordable-care-act-aca.

[20] Gruber, Jonathan. n.d. “Health Care Reform Is a ‘Three-Legged Stool.’” Center for American Progress (blog). Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2010/08/05/8226/health-care-reform-is-a-three-legged-stool/.

[21] “Budgetary and Economic Effects of Repealing the Affordable Care Act.” 2015. Congressional Budget Office. June 19, 2015. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50252.

[22] Rae, Matthew, Gary Claxton, and 2017. 2017. “Do Health Plan Enrollees Have Enough Money to Pay Cost Sharing?” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog). November 3, 2017. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/do-health-plan-enrollees-have-enough-money-to-pay-cost-sharing/.

[23] Garfield, Rachel, Anthony Damico Published: Nov 01, and 2017. 2017. “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States That Do Not Expand Medicaid.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog). November 1, 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/.

[24] “Compare Proposals to Replace The Affordable Care Act.” 2017. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (blog). September 18, 2017. https://www.kff.org/interactive/proposals-to-replace-the-affordable-care-act/.

[25] “Reconciliation Recommendations of the Senate Committee on Finance.” 2017. Congressional Budget Office. November 26, 2017. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53348.

[26] Petryna, Adriana. 2004. “Biological Citizenship: The Science and Politics of Chernobyl-Exposed Populations.” Osiris 19: 250–65.

[27] Cooter, Roger. 2008. “Biocitizenship.” The Lancet 372 (9651): 1725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61719-5.

[28] Junges, José Roque. 2010. “Right to Health, Biopower and Bioethics.” Interface – Comunicação, Saúde, Educação 5 (SE): 0–0.

« Back to Glossary Index