Once a rare misfortune, peanut allergy has become a publicized pandemic (Waggoner, 2013). The recent upsurge in peanut allergy prevalence begs discussion of its historical significance, contemporary relevance, popular controversy, and political influence. This entry will consider clinical studies and sociological analyses to holistically define peanut allergies.

Definition of Peanut Allergies

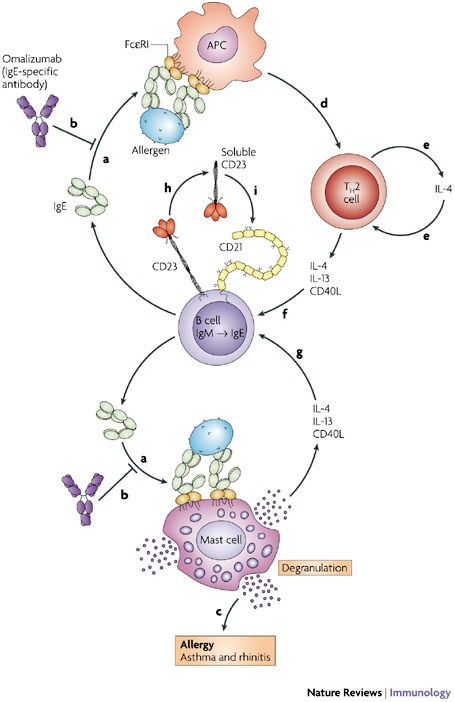

Gould and Sutton (2008) explain allergic responses as the immune system’s overreaction to some foreign irritant, known as an allergen (Figure 1). More precisely, an allergen fastens to the specific IgE antibodies that stud mast cells (Gould & Sutton, 2008). When a mast cell is stimulated in this fashion, it releases chemicals to initiate a physiological immune response (Gould & Sutton, 2008). Common symptoms of such a response include itching, airway constriction, and inflammation of the skin; the term anaphylaxis is used to describe an extreme allergic reaction that culminates in vascular collapse (Gould & Sutton, 2008). The majority of anaphylactic episodes and food-borne allergic deaths are caused by a single allergen: peanuts (Du Toit et al., 2015).

Figure 1 . Mechanism for an allergen-mediated immune response. The figure depicts the mutation of IgM antibodies into IgE antibodies, and the alternate pathways that initiate physiological allergic responses and the recruitment of immunity-relaying support cells (Gould & Sutton, 2008).

While there is no strict medical definition to constitute a peanut allergy, the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (2014) notes that an affirmative blood or skin test is normally involved in diagnosis. However, the high false positive rates for these indicators necessitate that a physical allergic response also be considered (ACAAI, 2014). Recognition of peanut aversion or allergy normally occurs during early childhood, with only a 20% chance of “outgrowing” the sensitivity (National Institute of Health, 2017). The unfortunate longevity of the condition is compounded by its invincibility; there is no recognized cure for peanut allergy, and an immediate epinephrine injection is the only known treatment for severe symptoms (Avery et al., 2003). Now afflicting nearly 1% of British and North American children, peanut allergies were once much less common and controversial (Waggoner, 2013).

Historical Context

The first swell of public allergy awareness began in the early 1960s, focused on asthma and other airborne irritations (Prescott & Allen, 2011). Food allergies were quietly documented for decades before gaining medical and media attention after 1980 (Waggoner, 2013). Peanut allergies were then deemed the most concerning food allergy by scientists of the early 1990s, producing a particular anxiety for the allergen (Waggoner, 2013). In addition to its recognized hardiness , peanut allergy was becoming more widespread: Sicherer et al. (2003) reported a doubled rate of childhood peanut allergy in the U.S. between 1997 and 2002 (Waggoner, 2013). Speculation soon surrounded such statistics, with other influential publications suggesting that popular panic had encouraged the recognition and self-reporting of peanut allergies (Waggoner, 2013).

The so-called “second wave” of allergy alarm surged in the early 2000s (Prescott & Allen, 2011). Official institutions and advocacy groups emerged in developed nations like New Zealand and Canada, and agencies received professional and public pressure to better recognize risk (Waggoner, 2013). In 2000, the United States issued government-sponsored advice that discouraged expectant mothers with atopy (a genetic predisposition to allergy) from consuming peanut products (Sicherer, 2017). In addition to prenatal avoidance of the allergen, neonatal ingestion was also cautioned (Sicherer, 2017). Despite the continuance of similar advice in Australia and the U.K., the U.S. revoked its peanut abstinence recommendation in 2008 (Sicherer, 2017). The visibility of the peanut allergen, however, remains as pronounced today as in its 2004 incarnation: policy still requires that food products processed alongside or with peanuts be labeled accordingly (Waggoner, 2013).

Current Popular and Social Context

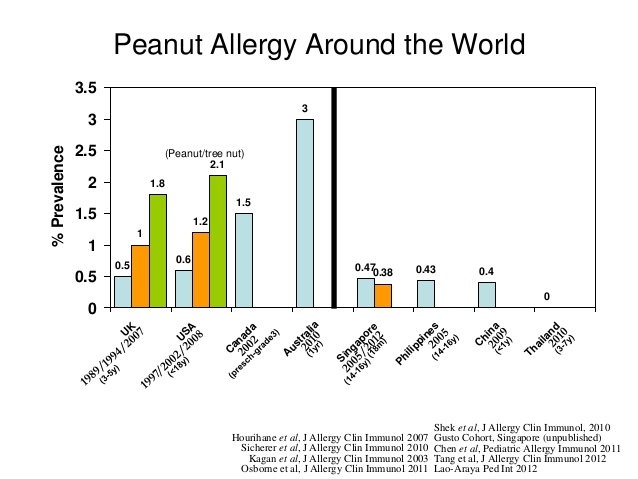

Previously endorsed practices to prevent peanut allergy have been fruitless at the population level (Du Toit et al., 2008). The ineffectiveness of peanut avoidance has since been explained by two hypotheses: sensitivity to peanut is not orally actuated, or peanut must be consumed to initiate an allergen resistance (Du Toit et al., 2008). Figure 2 illustrates that in many developing nations, where infant peanut consumption is high and environmental sterility is low, peanut allergy is much less common (Du Toit et al., 2008). In a test performed by Du Toit and colleagues (2008), increased peanut consumption during infancy was correlated with lower peanut allergy incidence in childhood–even when controlled for genetic dissimilarity, social class, and peanut processing standards. Such data encouraged the 2017 release of updated prevention guidelines: the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease now officially promotes early peanut introduction to infants, with timeframes determined by expressed allergy risk (Sicherer, 2017).

Figure 2. Prevalence of peanut allergy in westernized and Asian nations. The graph illustrates the rising prevalence over time in westernized nations, as well as the comparatively low rates of allergy in various Asian countries (Lee, 2015).

Just as formal health recommendations have adjusted to new peanut allergy knowledge, so too has the informal public arena. Medical professionals and media outlets have urged an increased awareness of peanut-allergic individuals, which has prompted educational and recreational institutions to create peanut-free zones (Waggoner, 2013). Such restricted areas are often demarcated with signage, as shown in Figure 3 . More extremely, some primary schools have banned peanut butter and various universities have designated nut-free campus housing options (Waggoner, 2013). Despite the growth of peanut-free programs, the only national allergy management guidelines–produced in 2013 by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention–are entirely voluntary (Food Allergy Research & Education, 2018). At the state level, the handling of allergies is multifarious; Tennessee guidelines promote epinephrine treatment and individualized health plans (IEP), while Texas prioritizes peanut elimination and allergy awareness (Food Allergy Research & Education, 2018). These well-intentioned accommodations can often be ostracizing for peanut-allergic children and adults. In a study by Avery et al. (2003), children with peanut allergies reported a significantly decreased quality of life when compared with a cohort of type 1 diabetics. Results further revealed that children with peanut allergies experience more anxiety when making dietary decisions, leaving home, and engaging in physical activity. Concern over the livelihood of allergic individuals and their unaffected peers has stimulated great public debate (Waggoner, 2013).

Figure 3. Nut-free zone signs outside a classroom window. The posters are exemplary of peanut allergy’s extreme visibility in educational settings (Coffee & Carpool, 2018).

Topical Perspectives

The escalation of peanut allergy’s diagnosis rate and social priority has become a controversial topic. Vaccination, another disputed issue surrounding the well-being of youth, is comparable to allergy in various respects. For both cases, the underlying medical logic is less contested than related health outcomes; inconsistent data and public conversation have muddied the perception of each subject matter. Vaccination and peanut allergy action similarly serve to benefit people with compromised immune systems. However, the majority is susceptible to vaccine-covered pathogens while a small minority is reactive to peanut. Vaccines and allergies both relate individual health to that of the population, but they do so in different spheres: vaccination is a public health concern because of the potential for communicable spread of a virus, while peanut allergies are more concerning for a populace’s social experience.

Among medical professionals and the general population, two camps have been established: one recognizing peanut allergy as a legitimate epidemic, and another regarding it as an ungrounded popular mania (Waggoner, 2013). The former group sees the rise of peanut allergies as a result of a medical crisis (Waggoner, 2013). One possible catalyst for this peanut allergy epidemic is Strachan’s (1989) hygiene hypothesis, which posits that the increased microbial sterility of westernized childhood has caused immune systems to recognize common stimulants as foreign threats–triggering unnecessary allergic responses (Okada et al., 2010).

Contrastingly, others believe that the recorded increase in peanut allergy prevalence may “reflect increased awareness among consumers and health professionals,” rather than an authentic spread of the condition (Waggoner, 2013, p. 52). Under this ideology, the public has dramatized a rare affliction to appear widespread and publicly concerning (Waggoner, 2013).

Aside from the epidemiological debate surrounding peanut allergies, the surveillance of peanut-allergic children is also contentious. Some argue that it is the responsibility of institutions to accommodate all persons, while others believe that taking extreme measures to comfort a small faction is unfair to the vast majority.

Political Connotations

Increased peanut allergy awareness exemplifies the influence of media and medical advice on popular opinion. Particularly, unsupported government-sponsored recommendations may have actually placed infants at a higher risk for developing peanut allergies–and the public still complied (Du Toit et al., 2008). Federal institutions are not alone in their influence; corporations have also participated in the shaping of peanut allergy’s reputation (Waggoner, 2013). For example, lawyers representing peanut-productive states resisted the Congressional motion to create peanut-free areas on aircrafts, thus introducing a commercial component to peanut allergy attention (Waggoner, 2013). In this way, dominant political and economic structures are exerting Foucauldian biopower on the general public, using their influence to dictate how human bodies behave in normal society (Foucault, 1984). Indicatively, school food policies decide which bodies are welcome; pharmaceutical companies establish the price for life-saving epinephrine; corporate systems influence the publicity and perception of peanut products; and medical testing and treatment centers diagnose the population’s allergy-related conditions. The immense weight of such institutions on peanut-allergic individuals is exemplary of biopower.

It is also relevant to consider the disproportionate public attention granted specifically to peanut allergies, contrasting the relative inattention to other food allergens. The timing of infant peanut introduction within the updated guidelines is based upon egg sensitivity and eczema, but much less dialogue surrounds these maladies (Sicherer, 2017). The unique politicization of peanut allergy, as opposed to other common allergies like milk, soy, egg, and seafood, is yet to be fully uncovered. With certainty, however, the utilitarian dilemma posed by peanut allergies is polarizing and political.

Additional Resources

Wüthrich, B., Däscher, M., Borelli, S. (2001). Kiss-induced allergy to peanut. Allergy, 56 (9), 913. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00302.x/full

● The above source describes an incident in which an adult experienced an allergic reaction after kissing peanut-exposed lips–even after extensive teeth brushing and other precautions. This scholastic article points to the seriousness of some peanut allergy cases and the possible ways in which it can affect social participation.

Hunt, S. (2015). “Stay Safe, Live Healthy, & Eat Well with Food Allergies.” Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3uc3JN4HOU

● The TED talk linked above focuses on the bullying faced by food-allergic children, the struggle of making food choices with a severe allergy, and the ways through which a healthy lifestyle is still obtainable. The speaker also introduces a concept of health beyond the physical, emphasizing that wellness has many components.

No more peanut problems: New Topeka program treats peanut allergies (2018, March 1), WIBW News Now!. Retrieved from http://www.wibw.com/content/news/No-more-peanut-problems-New-Topeka-program-treats-peanut-allergies-475622523.html

● The extremely recent news article above discusses a new treatment for peanut allergy that consists of monitored, gradual exposure to the peanut protein. The patient of focus has now graduated to eating peanut products, still in a controlled fashion. This source offers an alternative to the avoidance procedures often advocated.

References

American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (2014). Peanut Allergy . Retrieved from

http://acaai.org/allergies/types/food-allergies/types-food-allergy/peanut-allergy

Avery, N.J., King, R.M., Knight, S., & Hourihane, J.O’B. (2003). Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 14 (5), 378-382.

Coffee & Carpool (2018). Keep Your Food Allergy Kids Safe at School With 11 Essential Tips. Retrieved from http://coffeeandcarpool.com/food-allergy-kids-safe-school/

Du Toit, G., Katz, Y., Sasieni, P., Mesher, D., Maleki, S.J., Fisher, H.R., Fox, A.T., et al. (2008). Early consumption of peanuts in infancy is associated in a low prevalence of peanut allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 122 (5), 984-991.

Du Toit, G., Roberts, G., Sayre, P., Bahnson, H.T., et al. (2015). Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. New England Journal of Medicine, 372 (1), 803-813.

Food Allergy Research & Education (2018). School Guidelines. Retrieved from

https://www.foodallergy.org/education-awareness/advocacy-resources/advocacy-toolbox /school-guidelines

Gould, H.J., & Sutton, B.J. (2008). IgE in allergy and asthma today. Nature Reviews Immunology, 8 (1), 205-217.

Lee, B.W. (2015). Prevalence of Food Allergies in Southeast Asia . Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/Adrienna/prevalence-of-food-allergies-in-se-asia-2015

National Institute of Health (2013). Five CTSAs Enable NIH-Funded Research on Innovative Allergy Therapy. Retrieved from https://ncats.nih.gov/pubs/features/five-ctsas-enable

Okada, H., Kuhn, C., Feillet, H., & Bach, J.F. (2010). The ‘hygeine hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 160 (1), 1-9.

Prescott, S. & Allen, K.J. (2011). Food allergy: Riding the second wave of the allergy epidemic. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 22 (2), 155-160.

Sicherer, S.H. (2017). New advice for preventing peanut allergy in young children . Retrieved from

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/new-advice-for-preventing-peanut-allergy-in-young -children_us_58e3ad4be4b09dbd42f3da6f

Waggoner, M.R. (2013). Parsing the peanut panic: The social life of a contested food allergy epidemic. Social Science & Medicine, 90 (1), 49-55.