When one is terminally ill, or has a condition such as paralysis that makes the quality of life incredibly low, that patient may decide that life is not worth living. In these specialized cases, the suffering individuals may ask their care providers to terminate life, or in other words, to help them die. What is now called physician-assisted death, was originally referred to in the United States as physician-assisted suicide, or PAS (Terminology of Assisted Dying, n.d.). The medical definition of PAS is “The voluntary termination of one’s own life by administration of a lethal substance with the direct or indirect assistance of a physician” (Medical Definition of Physician-assisted suicide, para. 1, 2017). Today, the politically correct term that is used when a terminally ill patient asks his/her physician to intervene and end a life of suffering, is “physician-assisted death,” or Death with Dignity (Terminology of Assisted Dying, n.d). Whether or not the practice of physician-assisted death is medically ethical in the United States is a controversial topic. Heated discussion around these practices came to the U.S. in the 1990s, when Dr. Jack Kevorkian developed his suicide-machine and started aiding terminally ill patients in ending their lives (Nicol, N., & Wylie, H., 2006). Kevorkian brought physician-assisted suicide to the eyes of the nation and changed history forever. Through his practices, Dr. Jack Kevorkian forced America and its healthcare providers to consider an important question, “what should doctors do when struggling patients want to die?” (Jack Kevorkian and the Right to Die, 2015). Our society continues to struggle with a coherent answer to this important question today.

Physician-assisted death has been legal in the Netherlands for far longer than in the United States. Approximately twenty years before the United States began advocating for physician-assisted death, in the 1970’s, “the Dutch courts began to tolerate physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia for terminally- ill, competent patients. By the early 1980’s, the medical profession and courts in the Netherlands had established guidelines for physicians to perform assisted suicide and euthanasia. [And finally], in 1984, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands accepted physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia, not only for terminally-ill patients, but also for chronically-ill or elderly patients whose deaths were not otherwise imminent” (Canady, p. 1, 1996). The concept of physician-assisted death laws had not even been considered in the U.S. before the 1990s, but it is speculated that these sorts of practices occurred in secrecy behind closed doors well before then. Jack Kevorkian brought the debate to the forefront of the nation and caused a legal and medical revolution that is still progressing today.

Inspired by nations like the Netherlands, in 1988, Dr. Jack Kevorkian, a registered doctor in the state of Michigan, began a mission to help terminally ill patients with severe suffering to carry out their wishes and end their lives when suffering became unbearable. To do so, Kevorkian came up with a “suicide machine” (Nicol, N., & Wylie, H., p. 142 -143, 2006). The machine consisted of three liquids that were connected to the patient through an IV. Medically, “The saline solution was to be used as a carrier and to keep the vein open. The Seconal was to sedate the patient, and the potassium chloride was used to interrupt the body’s electrical signals and stop the heart” (Nicol, N., & Wylie, H., p. 143, 2006). The artifice was carefully crafted so that Kevorkian could avoid the charge of murder. First, Kevorkian would begin the saline IV drip, but then it was up to the patient to flip a switch that would release the second two chemicals and ultimately terminate life (Nicol, N., & Wylie, H., p. 143, 2006). The state of Michigan, aware of Kevorkian’s practices, initially prosecuted the doctor on four separate occasions before 1998.

The first three times Kevorkian faced trial, he was found not guilty. The state had no laws against assisted suicide at the time. Then on September 1st, 1998, a Michigan state law went into effect that stated, “planning, participating in, or providing the means for a suicide is a felony, punishable by up to five years in jail” (Cohn, para. 3, 1998). Being a radical doctor insistent upon change, Kevorkian was quick to test the legal system. He began video-taping his patients, which he would then show to the grand jury when facing his fourth trial. Jurors were brought to tears by the moving story of Kevorkian’s “suicide” patients and the trial ended in a mistrial (Charatan, 1999). The taping of his patients became important later on, as media furor surrounding the debate became essential to the later legalization of Death with Dignity acts.

After escaping legal repercussions four consecutive times, Kevorkian decided to heighten the stakes of his practices. The doctor would stretch the debate from physician-assisted suicide, to euthanasia, as is legal in the Netherlands (Jack Kevorkian and the Right to Die, 2015). Now, the “switch” did not have to be flipped by the patient, Kevorkian would administer the lethal injections himself. On November 22nd, 1998, a 60 Minutes episode on Kevorkian’s euthanasia practices was aired on CBS. More than 15 million Americans tuned in “to see Kevorkian administer three lethal injections to Thomas Youk, a 52-year-old man with Lou Gehrig’s disease, and then monitor a cardiogram as Youk slipped into death” (Cohn, para. 1, 1998). When Michigan state came after Kevorkian for his fifth and final trial, the doctor was found guilty (Charatan, 1999). Kevorkian was sentenced to eight years in jail on a, “second-degree murder conviction after he had erased the thin, yet legally indelible, line separating assisted suicide from euthanasia. No longer content with merely providing patients with the means to take their own lives, the doctor did the deed himself” (Haberman, para. 5, 2015). While Kevorkian was no longer able to grant his patients’ wishes to die on his own, practices of physician-assisted death did not end here. The media awareness that became inherent to the debate when Kevorkian showed the world videos of his dying-patients’ wishes, was essential to ultimately passing laws that would allow Death with Dignity. The videos of these men and women alerted some of the general public that this was not in fact manslaughter or involuntary killing, but rather, the most desperate wishes of Kevorkian’s patients. Many other terminally-ill men and women across the nation had stories similar to those that were shown in the 60 Minutes episode in 1998.

Throughout Kevorkian’s legal and medical battles of the 1990’s, other doctors, such as NY physician Dr. Timothy Quill aided Kevorkian in the fight for patients’ right to die. Shortly following Kevorkian’s first trial, Quill published an article in a New England medical journal, marking “the first time a main-stream physician had publically confessed to helping a patient take her own life” (Jack Kevorkian and the Right to Die, 2015). The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where he ultimately lost (Jack Kevorkian and the Right to Die, 2015). However, Kevorkian’s battle did have some success. The most influential person he reached was Barbara Coombs Lee from the state of Oregon. Lee is a private attorney, counsel to the Oregon State Senate, and also the “chief petitioner for Oregon’s death with Dignity Act” (Barbara Coombs Lee, para. 1, n.d.). Lee helped make Oregon the first state in the U.S. to pass a law permitting physician-assisted death, after the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that “there is no constitutional right to die and that this is a matter for the states to decide” (Haberman, para. 10, 2015). The issue was now up to the congressmen and women, political activists, and physicians in each of the states, to determine if Death with Dignity should be allowed. Kevorkian’s practices sparked the national debate that lives on today.

On October 27th, 1997, the state of Oregon became the first in the U.S. to pass a Death with Dignity law. This act allowed, “terminally ill state residents to receive prescriptions for self-administered lethal medications from their physicians. It does not permit euthanasia, in which a physician or other person directly administers a medication to a patient in order to end his or her life” (Chin et al., para. 2, 1999). Along with the law came a strict set of guidelines that must be adhered to before administering the medications. The patients must be terminally ill, and not be expected to continue living beyond six months of receiving the medication. Additionally, the patient must be psychologically and physically evaluated to be determined to be mentally competent and able to swallow the medication on his or her own. Finally, verbal agreement must be given on two separate occasions, separated by a minimum of fifteen days (Chin et al., 1999). Ultimately, while Kevorkian failed at legalizing euthanasia in the United States, the Oregon state model made significant progress in aiding suffering patients to end their lives at their own will. Bills such as the Death with Dignity act are a product of people like Kevorkian that view the life-prolonging procedures of modern medicine as detrimental to the well-being of terminally ill patients. Proponents of Death with Dignity believe that “the very measures that we once viewed as miracles of modern medicine can now be seen in a more critical light: Now we know that machines designed to prolong life can sometimes do nothing more than prolong the dying process” (Woodman, p. 2-3, 2001). To avoid prolonged struggling, proponents of Death with Dignity believe that the right to choose when one dies is essential.

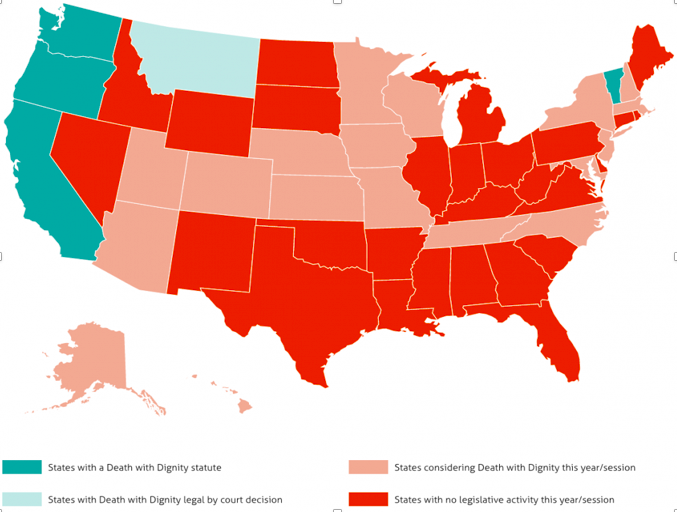

Today, euthanasia is still illegal in all states (Haberman, 2015). However, five states, including Oregon, Vermont, Washington, California, Colorado, and also the District of Columbia, have legalized physician-assisted death and follow models similar to Oregon’s “Death with Dignity Act.” Additionally, as seen on the map, in Montana, patients may receive aid with dying only with court-mandated approval (Chin et al., 1999). Supporters of “dying with dignity” believe that it is the patient’s right to choose when and how he or she dies, and that these men and women “looking for an early exit tend to be relatively well off and well educated” (Haberman, para. 9, 2015). Many advocates have begun to speak out for the individual rights of the terminally ill. Barbara Coombs Lee, who helped to pass Oregon Death with Dignity law, advocates for those who wish to end their lives with her organization, Compassion and Choices. Her goal is to protect the “rights” of those who are terminally ill (Barbara Coombs Lee, n.d.). The right to “death with dignity” has emerged as a social debate of “the last frontier for personal choice or, as some regard it, the ultimate human rights crusade” (Woodman, p. 3, 2001). Implementing these rights in America would therefore cause a nation-wide medical, legal, and ethical revolution (Woodman, 2001), which was Jack Kevorkian’s main goal when he began assisting terminally-ill patients to die in the 1990s. As of March, 2016, successes in passing Death with Dignity laws continued to increase. June 9th, 2016, is when California’s “End of Life Option” act went into effect, making it the fifth state to officially legalize Death with Dignity. While physician-assisted death was not legalized in Maryland as of 2016, the National Center for Death with Dignity announced that it is “committed to Maryland and will be working with the bill sponsors and other allies over the next year to bring the End of Life Option Act back in 2017” (Death with Dignity Acts, n.d.). Death with Dignity laws have allowed access to life-ending medications for many suffering individuals.

Since the Oregon Death with Dignity act went into effect, the number of patients prescribed the lethal medications has risen steadily. Twenty-four prescriptions were recorded to be administered after the law went into effect in 1998. In contrast, approximately one hundred and fifteen prescriptions were written for the medication in 2014. While this number seems high, it was found that approximately one-third of the patients who end up asking for the medication, never take it. In 2014, of the 155 patients prescribed the life-ending drugs, only 105 individuals actually died from consumption (Haberman, 2015). In total, between the years of 1998 and 2015, 1,372 residents of Oregon were able to obtain the lethal Death with Dignity drugs, and of those residents, 859 actually died from ingestion. The 1,372 residents of amount to “less than two-tenths of 1 percent of the nearly 530,000 people who died in Oregon during that period” (Haberman, para. 13, 2015). Statistics such as this, which point out that physician-assisted death ultimately amounts to only a small fraction of total deaths within each state, provide proponents of Death with Dignity with a counter argument to the opponents that will argue the slippery-slope.

Opponents of Death with Dignity laws continue today to echo the arguments of that evolved when Kevorkian was still practicing medicine. As of March 2016. the Death with Dignity report stated, “bill in Arizona, Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, Utah, and Wisconsin [have gone] down in defeat or sidelined in one legislative way or another” (Death with Dignity Acts, n.d.). These bills fail to pass because many express concerns of the slippery-slope. These opponents believe that as states continue to legalize physician-assisted aid in dying, “certain patients might feel they owe it to their overburdened families to call it quits. That the poor and the uninsured, disproportionately, will have their lives cut short. That medication might be prescribed for the mentally incompetent. That doctors might move too readily to bring an end to those in the throes of depression.” (Haberman, para. 8, 2015). The slippery-slope then, is that once disabled individuals begin to feel as if they are a burden to society, it will cause a domino effect so that many disabled individuals across the nation will want to die too. A prevalent activist group for these opponents is the “Not Yet Dead” group. The activists oppose physician-assisted death, believing that its legalization is a “deadly form of discrimination” (Not Dead Yet Disability Activists, para. 1, 2016). Others oppose Death with Dignity on more spiritual and ethical grounds. These campaigners against the laws believe that “wresting control over death…represents metaphysical trespassing into God’s domain, and it would seriously violate the integrity of the medical profession and its age-old oath to “do no harm”” (Woodman, p. 4, 2001). These opponents believe that the right to terminate life is not in humans’ control. On the contrary, it is the doctors’ role to preserve life, and God’s role to determine when that life should end. Ultimately, since it is up to the states to decide whether or not to enact bills allowing physician-assisted death, it is unlikely the nation will come to a united consensus as to whether or not these practices are ethical in the near future.

Physician-assisted death is related to the politics of health through the Michel Foucault’s concept of biopower (Foucault, 2008). Anthropologist Paul Rabinow and sociologist Nikolas Rose use Foucault’s model to argue that the “vital character of living human beings” is subject to health systems “letting die and making live” (Rabinow & Rose, p. 195, 2006). The terminally ill that no longer wish to live are therefore “bio-defectors” as they are not letting the state control when they die. The State wants to make all of its citizens live, as their health and biology is the main means of control of populations. Therefore, it cannot and will not let its citizens die as long as the State is in control. Therefore, to be able to die at one’s own will, physician-assisted death patients must defy the State. It is when they choose to defy the state that these individuals become bio-defectors from the biopolitical State in which we all live.

Additionally, physician-assisted death relates back to Fischer’s idea of “ready-to-consent,” populations, and is a main concern of opponents of these laws. Defined by Fischer, a “ready-to-consent” population, is a group of people that do “not have better alternatives than participation in clinical trials” (Fischer, 2007). While physician-assisted death is not a clinical trial, opponents are concerned that those who believe that they are a burden to their families or those with psychiatric diagnosis, might become “ready-to-consent” to dying, as it is seen as the only viable solution. In other words, opponents believe that as PAS becomes widespread through legalization of Death with Dignity acts, then increasing population of bio-defectors will begin to end their lives. As these practices ultimately become commonplace in the United States, then populations will become ready-to-consent, even if that is not their true wish.

In conclusion, there are many pros and cons to this controversial debate. Thinking through the lens of biopower, however, may be most productive for the conversation of whether or not legalization of physician-assisted death is ethical. To do so, we must ask ourselves whether or not it should be under the State’s control to decide when one is allowed to die.

Works Cited

Barbara Coombs Lee, RN, PA, FNP, JD. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2017, from https://www.compassionandchoices.org/research/speakers/speaker-bcl/

Canady, C. T. (1996). Physician-Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia in the Netherlands. ProQuest

Congressional. Retrieved November 20, 2017, from https://congressional-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/congressional/result/congressional/pqpdocumentview?accountid=14816&groupid=95246&pgId=6dd56e3a-5bef-43a2-9ede-c0d208eec2b7#1044.

Charatan, F. (1999). Dr Kevorkian found guilty of second degree murder. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 318 (7189), 962. Retrieved November 17, 2017 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1174693/

Chin, A. E., Hedberg, K., Higginson, G. K., & Flemming, D. W. (1999). Legalized Physician-

Assisted Suicide in Oregon — The First Year’s Experience. The New England Journal of Medicine,(340), 577-583. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902183400724

Cohn, J. (1998, Dec 14). TRB from washington. The New Republic, 219, 6. Retrieved from http://login.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/212818026?accountid=14816

Death with Dignity Acts. (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2017, from https://www.deathwithdignity.org/

Fisher, J. A. (2007). “Ready-to-Recruit” or “Ready-to-Consent” Populations?: Informed Consent and the Limits of Subject Autonomy. Qualitative Inquiry : QI, 13(6), 875–894. Retrieved September 20, 2017, from http://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407304460

Foucault, M., & Ewald, F. (2008). Society must be defended: lectures at the Collége de France, 1975-76. London: Penguin.

Haberman, C. (2015, March 22). Stigma Around Physician-Assisted Dying Lingers. Retrieved November 17, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/23/us/stigma-around-physician-assisted-dying-lingers.html

Jack Kevorkian and the Right to Die [Video file]. (2015, May 24). Retrieved November 17, 2017, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J_EKwSXOsVE

Nicol, N., & Wylie, H. (2006). Between the Dying and the Dead : Dr. Jack Kevorkian, the Assisted Suicide Machine and the Battle to Legalise Euthanasia. London: Vision. Retrieved November 17, 2017, from http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook?sid=6a4c9d6c-32ac-4250-8f57-e6fc1d297c73%40sessionmgr104&vid=0&format=EB

Not Dead Yet Disability Activists. (2016, July 05). Retrieved November 17, 2017, from http://notdeadyet.org/assisted-suicide-talking-points

Rabinow, P., & Rose, N. (2006). Biopower Today. BioSocieties,1(2), 195-217. doi:10.1017/s1745855206040014

Terminology of Assisted Dying. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2017, from https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=32841

Woodman, S. (2001). Last Rights : The Struggle Over the Right to Die. Cambridge, Mass: Perseus Books Group.

« Back to Glossary Index