Definition and Background

The postpartum period refers to the period following childbirth. This is an exciting yet stressful time and represents a period of physical, emotional, and social transition for new mothers (Haran et al. 1). Postpartum care refers to the health care for new mothers and newborn children during the postpartum period; this care generally lasts through the first six weeks after childbirth (Chen et al. 34). The aim of postpartum care in the United States is “to detect health problems of mother and/or baby at an early stage, to encourage breast-feeding, and to give families a good start” (Haran et al. 2). Since there are many differing views on maternal health care strategies, and since there is only limited research that focuses on maternal postpartum care, it is difficult to define an optimal approach to postpartum care (Chen et al. 38, Webb et al. 179). Generally, postpartum care in the United States may involve care in a facility immediately after birth, routine visits such as “well-baby checks,” educational programs, support groups, and home support by midwives or registered nurses (Haran et al. 3, Shaw et al. 218).

During the postpartum period, women encounter a host of physical and mental health issues that postpartum care aims to address. These issues are called maternal morbidities, which the WHO Maternal Mortality Group defines as “any health condition attributed to… pregnancy and childbirth that has a negative impact on the woman’s wellbeing” (Meaney et al. 1). Examples of frequently reported physical issues include: fatigue or tiredness, headaches, nausea backaches, constipation, abdominal pain, frequent urination or the feeling of having to urinate frequently, and breast soreness (Webb et al. 181). Nearly 70% of women report experiencing at least one physical problem within the first postpartum year (Haran et al. 2). This high incidence of maternal morbidities reveals the necessity for adequate postpartum care, since these physical issues can limit a mother’s ability to undertake her daily tasks and can increase feelings of “powerless[ness]” and depression (Haran et al. 2, Meaney et al. 2). A study of Philadelphia women found that “the presence of postpartum physical health problems undermines the functional health status and increases the emotional distress, including depressive symptoms” of postpartum women (Webb et al. 185). Many women experience these mild depressive symptoms, referred to as postpartum “blues,” during the postpartum period; symptoms include low energy, fatigue, and sleep and appetite problems (World Health Organization 127). Some women, however, may struggle with a more severe depression. A recent systematic review has shown that support from a health care professional may be the best method to combat these postpartum depressive symptoms (Shaw at al. 219). Postpartum care programs, therefore, play a significant role in the reduction of maternal morbidities, both mental and physical, that mothers encounter during the postpartum period.

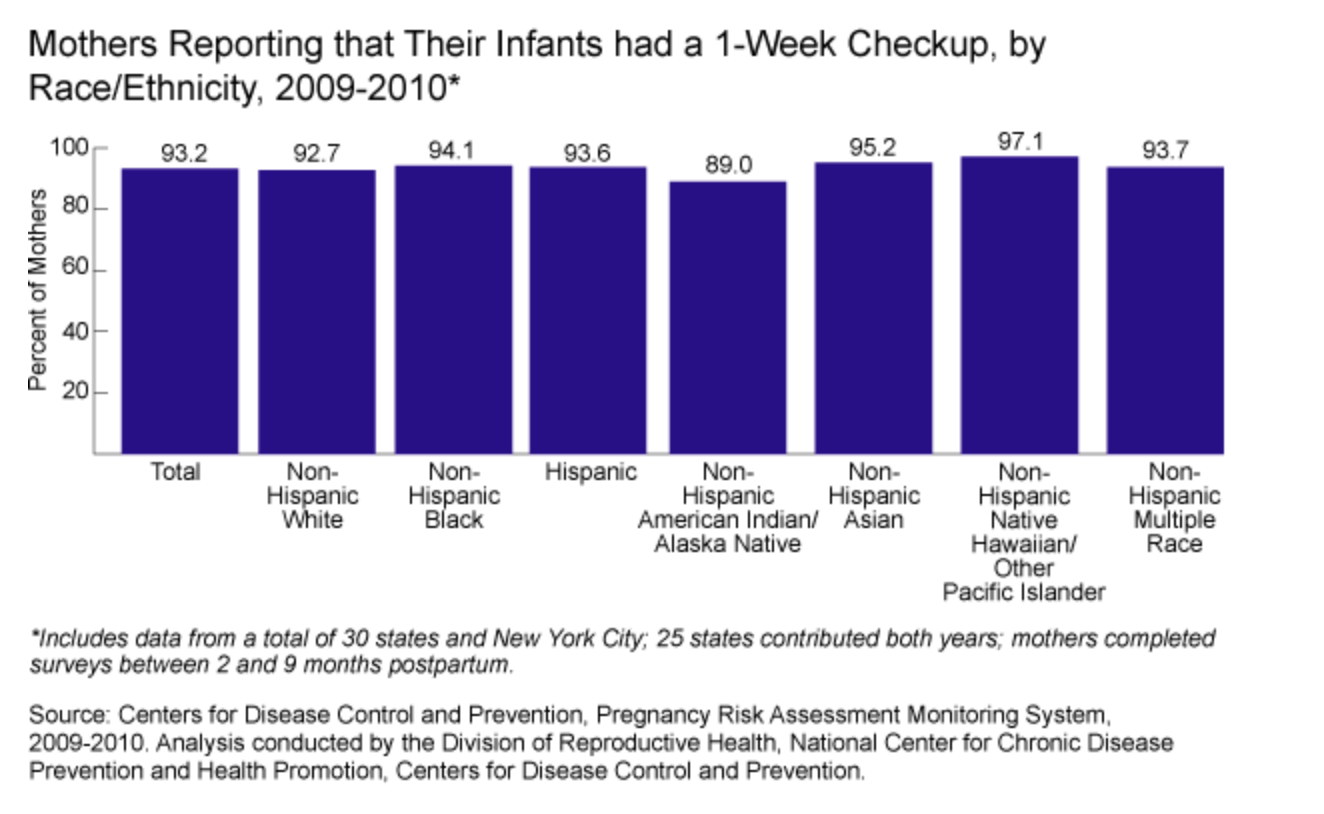

In 2011, the World Health Organization released a handbook for healthcare providers that contained comprehensive recommendations for postpartum maternal care. One of the first recommendations is that women should not be discharged before twenty-four hours after giving birth, and that during this time, the mother and baby should be monitored in the case that any complications arise (World Health Organization 123). The handbook then offers more details for longer-term postpartum care following the discharge, providing recommendations regarding postnatal visits, maternal nutrition, rest and sleep, maternal personal hygiene, infant feeding, and establishing a healthy home environment (World Health Organization 123). One example of a specific recommendation concerns the timing of postnatal visits, for which the handbook lays out a fairly specific schedule:

Image 1. Source: World Health Organization. “Counselling for Maternal and Newborn Health Care: A Handbook for Building Skills.” Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn, 2011. Page 124. This table comes from the WHO handbook about maternal care. It details their recommendations regarding the optimal timing visits to a health care provider during the postpartum period.

The creation of specific guidelines for postpartum care aims to improve the healthcare outcomes of new mothers and their babies. One reason that such guidelines are beneficial is that they offer advice to health care professionals on how to treat their patients in a variety of situations (Haran et al. 2); the intended audience for this WHO handbook was, after all, health care providers. A second reason that guidelines are valuable is that they may have an impact on policy, which would help create a model for quality care (Haran et al. 2). Interestingly, these guidelines have had little impact on the United States, which lacks national policies pertaining specifically to maternal health (Chen et al. 37).

Context: United States Postpartum Care

History

For many years, United States childbirth and postpartum practices followed the “social childbirth philosophy;” these practices were heavily influenced by English practices (Papagni and Buckner 11). In following the social childbirth philosophy, women went through labor and gave birth in their homes, surrounded by “lay female friends, relatives, and traditional midwives” (Papagni and Buckner 11). The role of these attendants was to “sustain the strength” of the laboring mother (Papagni and Buckner 11). The social aspects of these practices are exhibited by the presence of many female relatives and friends and the childbirth event. After giving birth, new mothers “remained with [their] female support system[s] for a period of ‘lying in’” (Papagni and Buckner 11). The purpose of this “lying in” period was for the new mother to recover from labor and birth and to bond with her new child (Papagni and Buckner 11). This social childbirth philosophy persisted during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; by 1930, however, a shift occurred away from the social childbirth philosophy and towards a “medical-illness model” (Papagni and Buckner 11). This shift was likely due to the increasing popularity of physicians, and to technological advancements (Papagni and Buckner 11). As a result of this shift, the use of traditional midwives decreased, and women began to give birth to their babies in hospitals, usually “with the aid of primary male physicians” Papagni and Buckner 11). The female support system of the past was no longer present, neither during birth nor during the postpartum period.

Standard Methods of Care Today

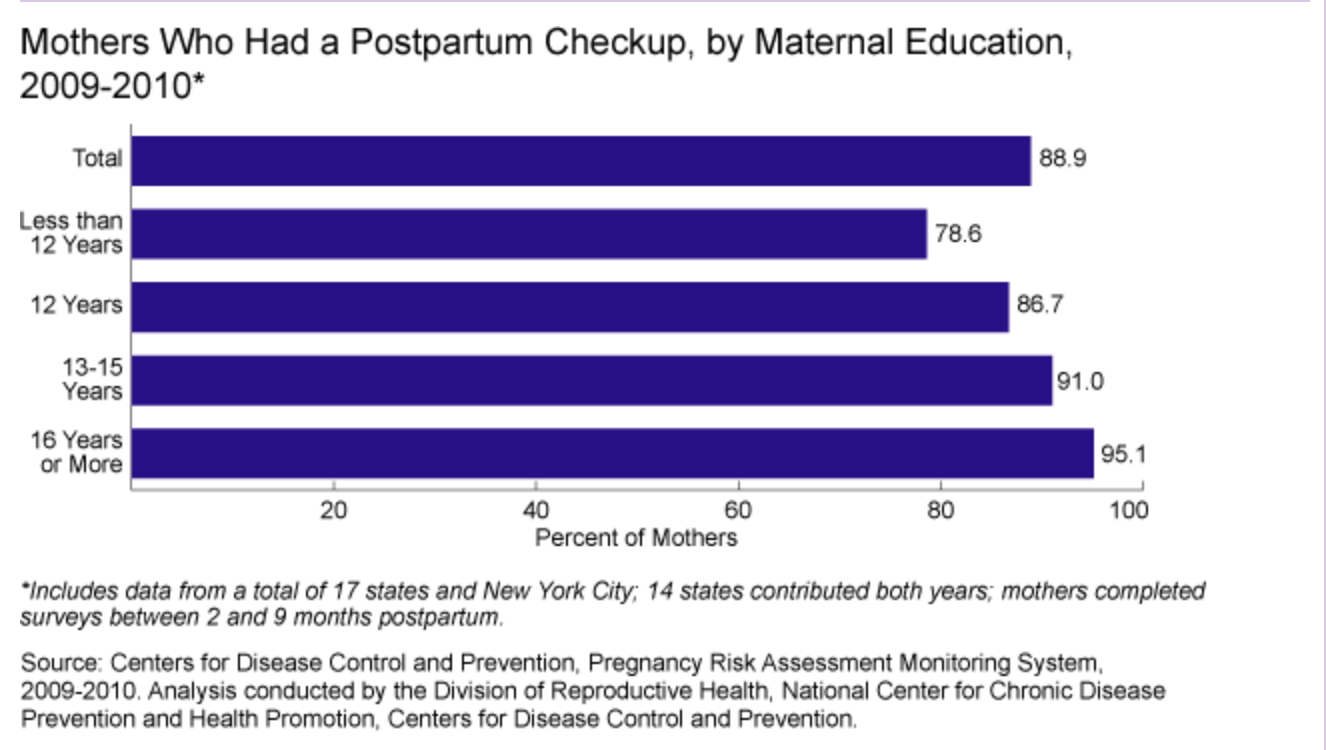

High quality postnatal care is essential because, according to the 1988 United States National Maternal and Infant Health Survey, poor maternal health is correlated with reduced children’s health. Unfortunately, current postpartum maternal care in the United States (U.S.) has often been regarded as inadequate in addressing maternal health (Chen et al. 34). Today, standard postpartum care in the U.S. does not include “early or frequent assessments,” and typical postpartum office visits focus “primarily on gynecological screening and contraception” (Albers and Williams 370). Additionally, there are no “specific national strategies, plans, or policies” in place to ensure that women receive postpartum care; as a result, many U.S. mothers lack understanding of healthy postpartum practices (Chen et al. 37). Standard regimens of postpartum care involve visits to the obstetrician for the mother, and trips to the pediatrician for the infant, referred to as “well-baby checks” or “well-baby exams” (Haran et al. 2). At well-baby checks, the doctor will examine the infant to assess its physical health, but these appointments also serve as an opportunity for a mother to develop a relationship with the pediatrician (“Postpartum Visit”). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the first well-baby exam occur within the first three to five days after birth. In 2009-2010, 93.2% of American women reported that their infant had a checkup within the first week after birth (“Postpartum Visit”).

Image 2. Source: “Postpartum Visit and Well-Baby Care.” Child Health USA 2013, Health Resources and Services Administration. This chart shows that a vast majority of surveyed American women, regardless of race, were able to bring their infant to receive a postpartum checkup within the first week after birth.

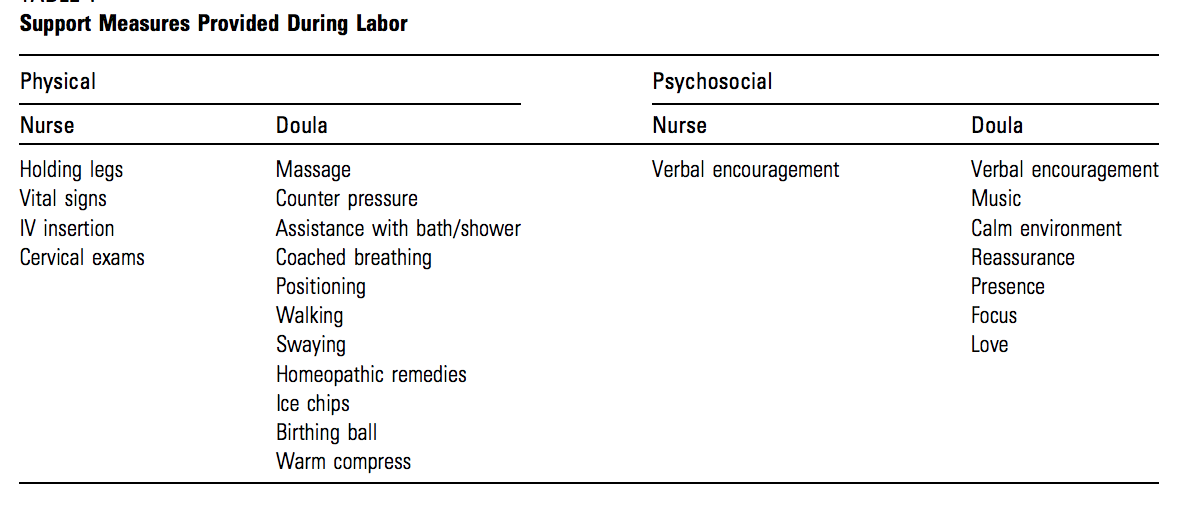

In postpartum care visits that focus on maternal health, a physician will examine the mother for “pregnancy-related complications,” “screen for postpartum depression,” and “provide counseling on infant care and family planning” (“Postpartum Visit”). The education portion of these visits is essential to provide mothers, especially first-time mothers, with knowledge about childcare and parenting skills. Education for first time mothers is particularly necessary since these mothers have never had a child before, and therefore may be less knowledgeable about infant care, due to their lack of experience. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists suggests that women should have one of these checkups between four to six weeks after delivery, near the end of the postpartum period. In 2009-2010, 88.9% of surveyed mothers had the suggested postpartum checkup.

Image 3. Source: “Postpartum Visit and Well-Baby Care.” Child Health USA 2013, Health Resources and Services Administration. This graph displays the percentage of surveyed women who indicated that they did have a postpartum checkup. It is interesting to note the correlation between the increasing rate of checkups with increasing years of maternal education.

Unfortunately, many studies have found that American women are generally unsatisfied with the current system of postpartum health care (Declercq et al. 2007, Coates et al. 2014, Wardrop and Popadiuk 2013). One study of postpartum women found that they felt “mistreated” and “ignored” by the healthcare system; they felt there were “not listened to, not asked how they were feeling,” and “not treated as equals” (Coates et al. 7). It appears that these mothers were disappointed by the lack of attention that their physicians paid to their mental health status and concerns. Another study that focused on women with postpartum depression and/or postpartum anxiety found that women felt that they got neither the “amount” nor “type” of support they desired from their providers (Wardrop and Popadiuk 12). Some of these women noted that they felt that their doctors “did not ask the right questions” regarding their experiences, which prevented them from understanding or addressing the women’s struggles (Wardrop and Popadiuk 12). These studies demonstrate clearly that the current postpartum healthcare system needs improvement in order to improve maternal satisfaction. One study noted that mothers felt most satisfied when they had developed a personal relationship with one specific physician who knew and understood well their situation (Coates et al. 8). A second study found that mothers were also more satisfied by care programs that included home visitation, as compared to clinic or hospital visits (Shaw et al. 218). Perhaps it would be beneficial for these care strategies to be incorporated into new developments in the United States postpartum health care system.

Alternative Methods of Care: In-Home Postpartum Care

In an attempt to increase their overall satisfaction with the care they receive during the postpartum period, many United States mothers turn to alternative forms of postpartum care, which they often use in addition to care in clinical settings. One such element of postpartum care that can be used in addition the standard U.S. system of care is in-home postpartum care. In-home postpartum care is a “cost-effective and comprehensive” method of continuing care after a mother and baby are discharged from the hospital; It aims to “ease the transition between birth and parenthood” for new families (Pease and Begel 41). Historically, in-home postpartum care has been provided by a mother’s female family members or friends, but due to modern day challenges, this is less common (Pease and Begel 41). One such challenge is that, often, female relatives and friends work full-time jobs and are not available to provide continuous care for the new mother and baby (Pease and Begel 41).

In-home care often involves multiple-hour-long home visits over the span of two or three weeks at the beginning of the postpartum period (Pease and Begel 40). During these visits, care providers provide comprehensive care to new mothers and families. The standard responsibilities of in-home care providers are listed in the table below.

| Responsibilities of In-Home Care Providers |

| – Check-in with the new family daily using assessment questions to determine if the family’s recovery is within the range of normal

– Educate new families about infant care – Model appropriate parenting behavior – Problem-solve with new parents – Work with new mother to learn the basics of caring for herself – Provide basic infant feeding education as well as basic breastfeeding instruction – Support the emotional needs of the family |

Table 1. Source: Pease, Susan, and Heidi Begel. “In-Home Postpartum Care: Much More than Just Good Advice.” International Journal of Childbirth Education; Minneapolis. 1996.

In the United States today, in-home postpartum care is supplied privately; however, in many other countries, in-home care is provided to mothers via a public healthcare system (Pease and Begel 41). So, in the U.S., women must seek out private companies in order to receive in-home care. One example of an in-home postpartum care service is The Fourth Trimester, Inc. Fourth Trimester was founded in 1990 with the goal of making in-home postpartum care “universally available to birthing families through the managed care system” (Pease and Begel 40).

Alternative Methods of Care: Doulas

Another alternative form of postpartum care is the use of doulas, which has recently become an increasingly popular choice among United States mothers. In 2002, five percent of women who gave birth in the U.S. used a doula for support (Lantz et al. 110). A doula has a specific role that differs from that of midwives or nurses: a doula is a “supportive companion” who is professionally trained to provide social and emotional support to new mothers during labor and the postpartum period (Lantz et al. 110, Gilliland 762). A doula focuses on the non-clinical aspects of care (Gilliland 762). Doulas are classified as “paraprofessionals,” meaning that they have lower levels of training and work together with another professional (Lantz et al. 110). Interestingly, while there is a certification process that doulas may choose to go through, there are no regulations in any state in the U.S. that requires a doula to be registered or certified (Lantz et al. 110). The four main certifying organizations for doulas are: Doulas of North America, the International Childbirth Education Association, the Childbirth and Postpartum Professional Association, and the Association of Labor Assistants and Childbirth Educators (Gilliland 762). Not all doulas elect to go through the certification process, though it appears that most practicing doulas in the U.S. do (Lantz et al. 114).

The role of a doula is multifaceted; they provide physical, emotional, and social support to new mothers. Doulas of North America (DONA), a doula certification organization, defines the role of a doula in seven points:

- “To recognize birth as a key life experience that the mother will remember all of her life”

- “To understand the physiology of birth and the emotional needs of a woman in labor”

- “To assist the woman and her partner in preparing for and carrying out their plan for birth”

- “To stay by the side of the laboring woman throughout the entire labor”

- “To provide emotional support, physical comfort measures, an objective viewpoint, and assistance to the woman in getting the information she needs to make good decisions”

- “To facilitate communications between the laboring woman, her partner, and clinical care providers”

- “To perceive the doula’s role as one who nurtures and protects the woman’s memory of her birth experience”

From these goals, it is clear that a doula’s role goes beyond the clinical aspects of care. In many hospitals, emotional support of new mothers is typically the job of nurses, who are often too busy to focus on a mother’s emotional needs (Papagni and Buckner 12). So, a doula often acts as a supplement to a nurse in order to provide supportive care to a new mother. Some common methods of support provided by doulas are “massage, words of encouragement, coaching, education, a continuous presence, and other types of comfort and support” (Lantz et al. 110). The table below compares methods of support used by nurses and doulas when caring for laboring mothers; it

Table 2. Source: Papagni, Karla, and Ellen Buckner. “Doula Support and Attitudes of Intrapartum Nurses: A Qualitative Study from the Patient’s Perspective.” Journal of Perinatal Education. 2006.

One of the most crucial aspects of a doula’s role is to provide continuous care. A doula “remains familiar throughout staff changes, room changes, and visits for the physicians” (Gilliland 768). The benefits of such continuous support are well documented in research literature: data indicate that women who have continuous labor support have lower rates of anesthesia use, shorter labors, increased maternal satisfaction with the birthing process, more maternal-infant bonding, less anxiety about motherhood, and a lower incidence of postpartum depression (Gilliland 762, Lantz et al. 109, Papagni and Buckner 14). Many mothers choose to use doulas for these benefits of continuous emotional support (Papagni and Buckner 12).

The rise in use of doulas is occurring in the United States amidst debates about “what constitutes a quality childbirth experience,” including methods of postpartum care (Lantz et al. 115). The role of the doula is evolving in order to incorporate different philosophies and perspectives about normal care (Gilliland 762). While the future of doulas as a lasting institution in the United States system of postpartum care is unclear, it appears that they will likely continue to grow in popularity, as “[p]atients increasingly are satisfied” by their experiences when “a doula is present” (Gilliland 766).

Perspectives: Korean Sanhujori Centers

Korean traditions have “specific belief and practice systems for the postpartum period,” which are known as Sanhujori (Kim 109). Sanhujori is the concept of the “non-professional postpartum care after delivery” (Kim 107). According to Jeongeun Kim’s 2003 study, there are six principles of Sanhujori:

- “Invigorating the body by augmentation of heat and avoidance of cold”

- “Resting without working”

- “Eating Well”

- “Protecting the body from harmful strains”

- “Maintaining cleanliness”

- “Handling with the whole heart”

In Korea, the traditional belief is that failing to follow these guidelines of Sanhujori results in increased risk for the mother of illnesses and of Sanhubyung (Kim 109). Sanhubyung refers to health issues faced by middle-aged women that are attributed to lack of quality postpartum care (Kim 109). This means that those women who fail to sufficiently comply with the principles of Sanhujori in their postpartum period will face illnesses later in life because of it. Therefore, Korean mothers place a good deal of emphasis on their postpartum care. One study of Korean women with arthritis found that 36.7% of women attributed their condition to not following Sanhujori practices (Kim 110).

Traditionally, new mothers were cared for during the postpartum period by their mothers and mothers-in-law (Kim 108). Recently, however, with increasing number of women in the workforce, some new mothers are left without family members to care for them during this crucial time (Kim 108). This has necessitated the development of Sanhujori centers, which are postpartum care centers that aim to combine the traditional principles of Sanhujori with high quality, more modernized postpartum care (Kim 108). According to Kim’s 2003 study of Sanhujori centers, women are admitted between one and three days after delivery and the average stay lasts 17.6 days. Surveyed women reported that they chose to go to these centers because they desired higher quality care, and 61.7% said they would use the same Sanhujori center again (Kim 109). This is a fairly high level of approval, especially when compared to the level of dissatisfaction that American mothers feel with the United States postpartum care system. It is important to note, however, that since there are no protocols, laws, or quality controls that concern the establishment and regulation of new centers, Sanhujori centers are technically providing women with “unauthorized and unlicensed medical treatment” (Kim 108). This is interesting to consider in combination with the high satisfaction rates of women who utilize the centers; it appears that they are able to offer adequate care without these legal regulations. This might reflect a discrepancy in what the women consider to be quality care versus what the government may consider to be quality care, as the Sanhujori centers focus on traditional beliefs.

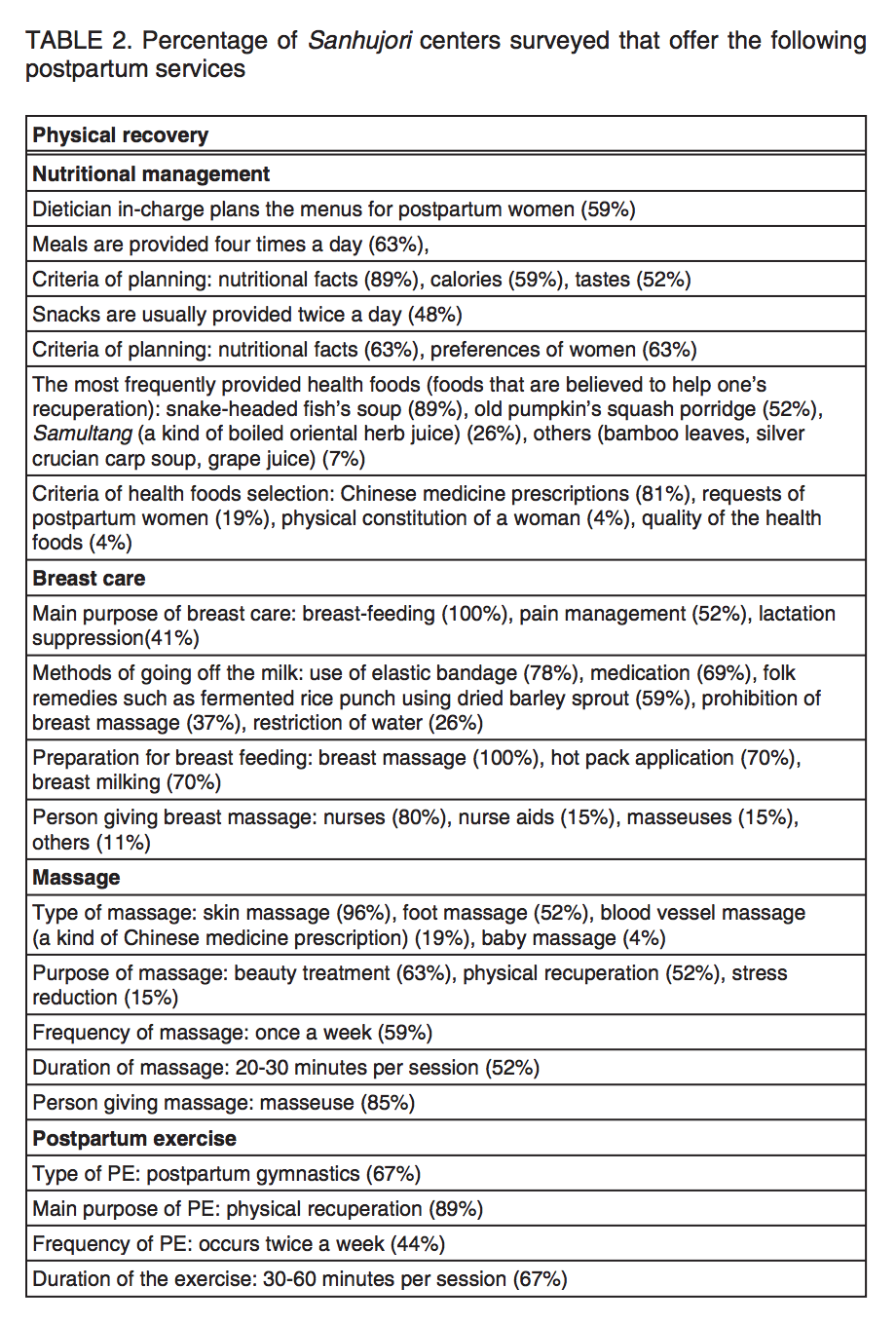

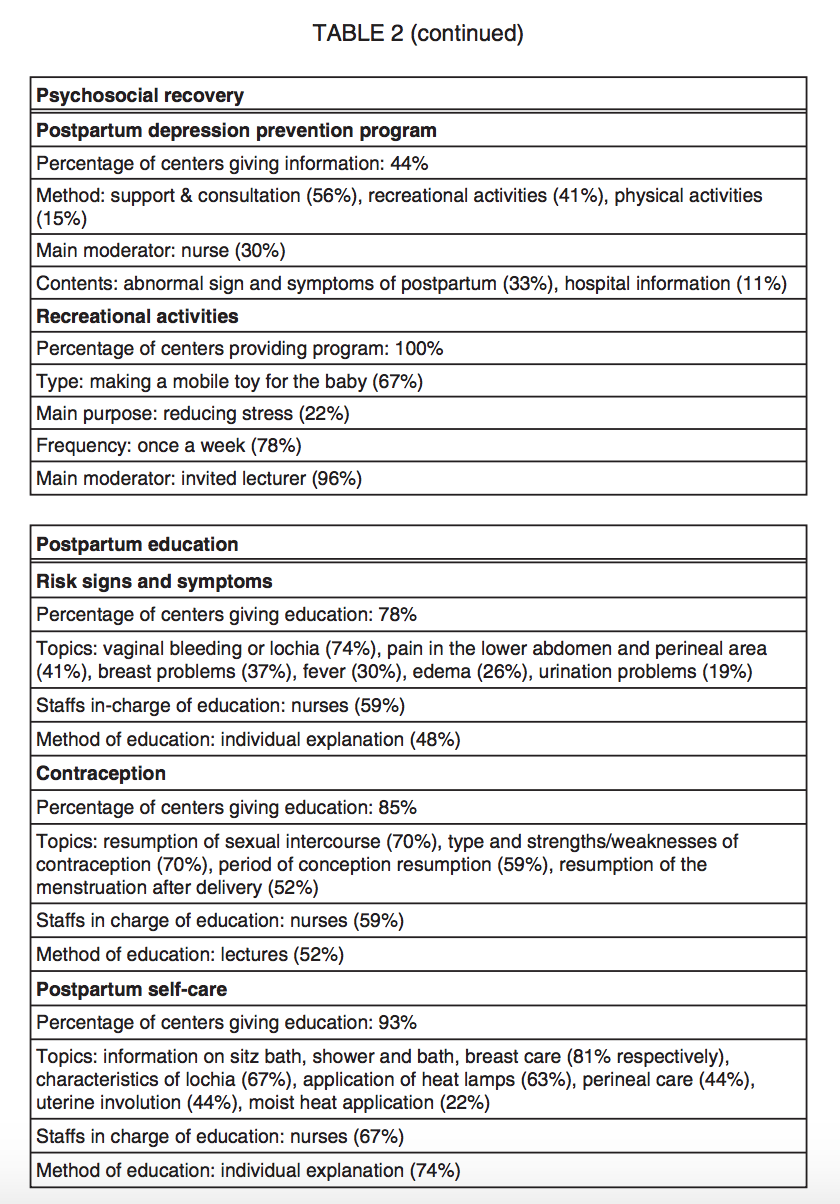

Some of the services offered at Sanhujori centers include: “physical recuperation, exercise, hygiene, infection prevention, breast feeding, baby bathing, cord care, mother-baby bonding, training of new parental roles, and family planning” (Kim 108). Kim’s study found that while “most centers try to comply with postpartum care protocols, some do not comply” (Kim 111). Noncompliance is possible since these centers do not have any laws or criteria to guarantee quality or regulate service offerings. Regarding nutrition, most centers provide women with foods that are considered “health foods” according to Korean tradition (Kim 111). Foods that are considered to be beneficial to postpartum women are foods that assist in “rapid recovery” and “increasing the mother’s milk (Kim 110). Unhealthy foods, on the other hand, are those which cause indigestion and “bad effects to mother’s milk” (Kim 110). Determining a certain food’s level of health appears to be relate to its perceived effects on the mother’s breastmilk. Accordingly, Kim’s study noted that all centers “provide breast massage for efficient breastfeeding” (Kim 111).

One area of care in which Sanhujori centers require improvement is in their educational programs. The programs at some centers do not discuss crucial topics such as risk symptoms and contraception (Kim 116). A lack of information in these areas may be detrimental to new mothers if they encounter issues during the postpartum period or beyond. Additionally, sometimes those in charge of the educational programs were not in the medical field (Kim 116). This may limit the ability of the programs to provide new mothers with accurate medical information. Kim argues that Sanhujori centers should create more “scientifically based medical services” in order to increase their quality of care (Kim 116).

Image 4. Source: Kim’s “Survey on the Programs of Sanhujori Centers in Korea as the Traditional Postpartum Care Facilities.” 2003. This table shows the percentage of Sanhujori centers included in Kim’s survey that offered certain services. For example, 63% of centers offered meals four times a day. This provides some insight into the quality and scope of offerings that one might find in a typical Sanhujori center.

Relation to Politics of Health

Postpartum care is related to politics of health through Conrad’s concept of medicalization. Conrad defines medicalization as “defining a problem in medical terms” and subsequently “using a medical intervention to treat it” (Conrad 3). According to this definition, the entire process of pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care has certainly been medicalized in recent times. Birth and maternal health care have become highly medical processes, but they were not always this way. In early nineteenth century America, care was “part of domestic life, guided by family traditions and the advice found in the medical or nursing manuals of the day” (Buhler-Wilkerson 1). This was true of all types of medical care, which includes prenatal and postnatal maternal care. If wealthy families did hire a physician, this medical care was “delivered in the patient’s home, most often with the assistance of female family members, neighbors, or occasionally a servant” (Buhler-Wilkerson 1). This certainly contrasts with the care of today, which largely takes place in hospitals and clinical settings. Much of postpartum care involves checkups and visits to pediatricians and obstetricians.

Conrad’s drivers of medicalization, biotechnology, patient as consumer, and managed care can be seen in the medicalization of birth and postpartum care (Conrad 5). Conrad explains that technology has often driven medicalization (Conrad 5). This can certainly be seen in the medicalization of childbirth and postpartum care, as technological advancements have led to more childbirth interventions. Conrad cites the invention of forceps as an example of medicalization (Conrad 5). Physicians began to use forceps routinely in the 1920s; In the 1940s, anesthesia became widely used (Papagni and Buckner 12). By 1950, most women were “not alert or not even conscious while giving birth” (Papagni and Buckner 12). In the 1960s, more powerful forms of anesthesia were developed, including continuous caudal anesthesia and continuous lumbar epidural anesthesia (Papagni and Buckner 12). In the 1970s, electronic fetal monitoring was introduced (Papagni and Buckner 12). These sorts technological advancements demonstrate drastic changes in the processes of childbirth and postpartum care. These advancements can be described in Conrad’s term biotechnological advancements; These certainly have contributed to the medicalization of childbirth and postpartum care.

Conrad’s second engine, the idea of patients as consumers, is also relevant to the medicalization of postpartum care. Conrad argues that the health care system has become “commodified and subject to market forces,” and as a result, “medical care has become more like other products and services” (Conrad 8). People have become “consumers in choosing health insurance plans, purchasing health care in the marketplace, and selecting institutions of care” (Conrad 8). This engine contributes to the medicalization of postpartum care because postpartum care is extremely expensive, especially for women in the United States who lack insurance. According to the Listening to Mothers II Survey, 37% of surveyed women had to pay for some maternity care bills out of pocket, while 1% faced the burden of paying the entire bill out of pocket (Declercq et al. 12). Additionally, doulas, whose services must be purchased privately in the United States, have become more like other goods and services in the market. The system of medical care has been transformed into a market with producers and consumers, and the postpartum care system is no exception. Conrad would argue that this commodification contributes to the medicalization, in this case, of postpartum care.

Conrad’s third engine of medicalization is managed care. Recently, “managed care organizations have come to dominate health care delivery in the United States” (Conrad 10). He explains that managed care “requires preapproval for medical treatment and sets limits on some types of care” (Conrad 10). This system of managed care can be seen in the postpartum care system in what elements of postpartum care are not covered by insurance, which places limits on the care that new mothers and infants are able to receive. Due to the presence of managed care, many new mothers are “obligated by their insurance plans to specific physicians or obstetric groups. (Gilliland 762). As a result, the best care provider might not be available to them (Gilliland 762). Some mothers attempt to bridge this gap in care by hiring doulas. Therefore, the system of managed care affects postpartum care by limiting the care that new mothers can receive.

The medicalization of postpartum care is not restricted to the United States, however. The Sanhujori centers of Korea also represent the medicalization of postpartum care. It is important to consider what may be the costs and benefits of this medicalization. What is the impact on infant and maternal mortality rates during the postpartum period? What is the impact of medicalized care on maternal satisfaction?

Additional Resources

- Jessica Shortall’s TEDTalk “The U.S. Needs Paid Family Leave”

In this TEDTalk, Shortall discusses the lack of both paid and unpaid maternity leave available to new mothers in the United States. This talk is relevant to the topic of postpartum care because it highlights one of the major issues faced by postpartum women who work outside the home. As shown by the anecdotes that Shortall scatters throughout the talk, insufficient maternity leave is detrimental to the health of new mothers, and consequently, to the health of their babies. The issue of maternity leave is a matter on which the United States system of postpartum care certainly falls short.

- Doulas of North America Website

- Professor Cecily Begley of Trinity College Dublin Discusses Overmedicalization of Childbirth

- Korea Today #CuriousInKorea Segment about Postpartum Traditions in Korea

Works Cited

Albers, Leah, and Deanne Williams. “Lessons for US Postpartum Care.” The Lancet; London, vol. 359, no. 9304, 2 Feb. 2002, pp. 370-71. ProQuest 5000, login.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/198983341?accountid=14816. Accessed 27 Feb. 2018.

Bar-Yam, Naomi Bromberg. “Becoming a Mother: Postpartum Is a Special Time.” International Journal of Childbirth Education; Minneapolis, vol. 11, no. 4, 31 Dec. 1996, pp. 4-6. ProQuest 5000, login.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/212873003?accountid=14816. Accessed 27 Feb. 2018.

Benahmed, Nadia, et al. “Vaginal Delivery: How Does Early Hospital Discharge Affect Mother and Child Outcomes? A Systematic Literature Review.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 17, no. 289, 2017, pp. 1-14. BioMed Central, DOI:10.1186/s12884-017-1465-7. Accessed 11 Feb. 2018.

Bower, Bradley C. Unlicensed Midwife. 26 Jan. 2007. AP Ima. Accessed 14 Feb. 2018.

Buhler-Wilkerson, Karen. No Place Like Home: A History of Nursing and Home Care in the United States. Johns Hopkins UP, 2001.

Chen, Ching-Yu, et al. “Postpartum Maternal Health Care in the United States: A Critical Review.” Journal of Perinatal Education, vol. 15, no. 3, Summer 2006, pp. 34-42. PubMed Central, doi:10.1624/105812406X119002. Accessed 8 Feb. 2018.

Cheyney, Melissa, et al. “Outcomes of Care for 16,924 Planned Home Births in the United States: The Midwives Alliance of North America Statistics Project, 2004 to 2009.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, vol. 59, no. 1, Jan.-Feb. 2014, pp. 17-27. Wiley Online Library, DOI:10.1111/jmwh.12172. Accessed 12 Feb. 2018.

Coates, Rose, et al. “Women’s experiences of postnatal distress: a qualitative study.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 14, 2014, pp. 359-74. ProQuest, DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-14-359. Accessed 15 Feb. 2018.

Conrad, Peter. “The Shifting Engines of Medicalization.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, PDF ed., vol. 46, Mar. 2005, pp. 3-14.

Declercq, Eugene R., et al. “Listening to Mothers II: Report of the Second National U.S. Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences.” Journal of Perinatal Education, vol. 16, no. 4, Fall 2007, pp. 9-14. PubMed Central, doi:/105812407X244769. Accessed 8 Feb. 2018.

Gilliland, Amy L. “Beyond Holding Hands: The Modern Role of the Professional Doula.” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, vol. 31, no. 6, Nov. 2002, pp. 762-69. Wiley Online Library, DOI:10.1177/0884217502239215. Accessed 26 Feb. 2018.

Haran, Crishan, et al. “Clinical Guidelines for Postpartum Women and Infants in Primary Care: A Systematic Review.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 14, no. 51, 2014, pp. 1-9. Bio Med Central, DOI:10.1186/1471-2393-14-51. Accessed 11 Feb. 2018.

Kim, Jeongeun. “Survey on the Programs of Sanhujori Centers in Korea as the Traditional Postpartum Care Facilities.” Women & Health, vol. 38, no. 2, 2003, pp. 107-17. Taylor & Francis Online, DOI:10.1300/J013v38n02_08. Accessed 14 Feb. 2018.

Lantz, Paula, et al. “Doulas as Childbirth Paraprofessionals: Results from a National Survey.” Women’s Health Issues, vol. 15, no. 3, May-June 2005, pp. 109-16. Women’s Health Issues, DOI:10.1016/j.whi.2005.01.002. Accessed 26 Feb. 2018.

Meaney, S., et al. “Women’s Experience of Maternal Morbidity: A Qualitative Analysis.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 16, no. 184, 2016, pp. 1-6. BioMed Central, DOI:10.1186/s12884-016-0974-0. Accessed 11 Feb. 2018.

Mothers Reporting that Their Infants had a 1-week Checkup, by Race/Ethnicity, 2009-2010. 2013. HSRA Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed 15 Feb. 2018. Chart.

Mothers Who Had a Postpartum Checkup, by Maternal Education, 2009-2010. 2013. HSRA Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed 15 Feb. 2018. Chart.

Papagni, Karla, and Ellen Buckner. “Doula Support and Attitudes of Intrapartum Nurses: A Qualitative Study from the Patient’s Perspective.” Journal of Perinatal Education, vol. 15, no. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 11-18. PubMed Central, doi:10.1624/105812406X92949. Accessed 27 Feb. 2018.

Pease, Susan, and Heidi Begel. “In-Home Postpartum Care: Much More than Just Good Advice.” International Journal of Childbirth Education; Minneapolis, vol. 11, no. 1, 31 Dec. 1996, pp. 40-41. ProQuest, login.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/212866814?accountid=14816. Accessed 27 Feb. 2018.

Percentage of Sanhujori Centers Surveyed That Offer the Following Postpartum Services. 2003. Taylor & Francis Online. Accessed 15 Feb. 2018. Table.

“Postpartum Visit and Well-Baby Care.” Child Health USA 2013, Health Resources and Services Administration, mchb.hrsa.gov/. Accessed 14 Feb. 2018.

Shaw, Elizabeth, et al. “Systematic Review of the Literature on Postpartum Care: Effectiveness of Postpartum Support to Improve Maternal Parenting, Mental Health, Quality of Life, and Physical Health.” Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, vol. 33, no. 3, Sept. 2006, pp. 210-20. Wiley Online Library, DOI:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00106.x. Accessed 14 Feb. 2018.

Vahration, Anjel, and Timothy R. B. Johnson. “Maternity Leave Benefits in the United States: Today’s Economic Climate Underlines Deficiencies.” Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, vol. 36, no. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 177-79. Wiley Online Library, DOI:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00330.x. Accessed 15 Feb. 2018.

Wardrop, Andrea A., and Natalee E. Popadiuk. “Women’s Experiences with Postpartum Anxiety: Expectations, Relationships, and Sociocultural Influences.” The Qualitative Report, vol. 18, 2013, pp. 1-24. ProQuest. Accessed 15 Feb. 2018.

Webb, David A., et al. “Postpartum Physical Symptoms in New Mothers: Their Relationship to Functional Limitations and Emotional Well-being.” Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, vol. 35, no. 3, Sept. 2008, pp. 179-87. Wiley Online Library, DOI:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00238.x. Accessed 13 Feb. 2018.

“What Is a Doula?” DONA International, www.dona.org/. Accessed 27 Feb. 2018.

World Health Organization. “Counselling for Maternal and Newborn Health Care: A Handbook for Building Skills.” Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn, 2011. NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304191/. Accessed 15 Feb. 2018.

—. “Schedule of Postnatal Visits for Mother and Newborn.” Counselling for Maternal and Newborn Health Care: A Handbook for Building Skills, by World Health Organization, 2011. NCBI. Table.

« Back to Glossary Index