Overview on Refugee Resettlement

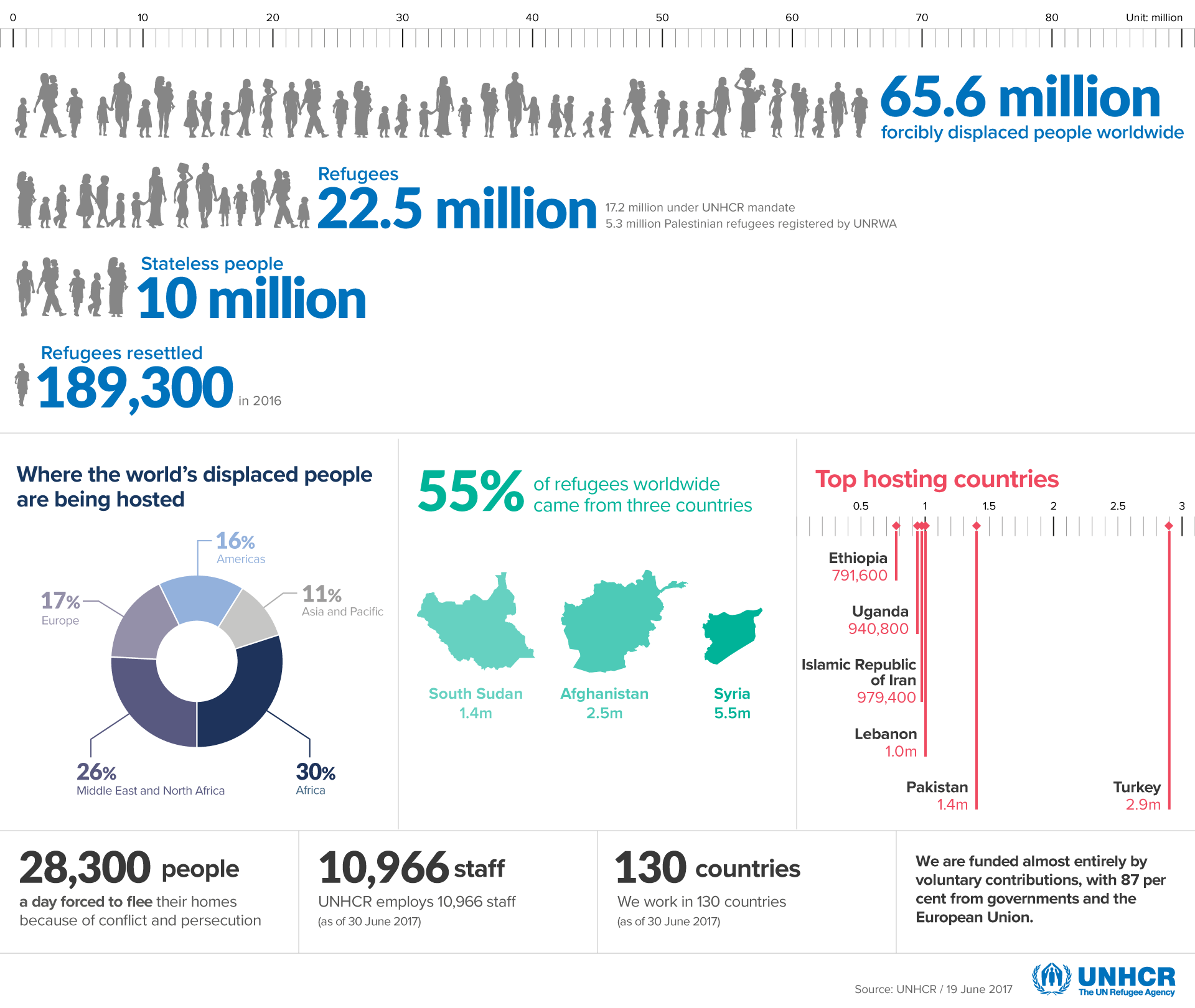

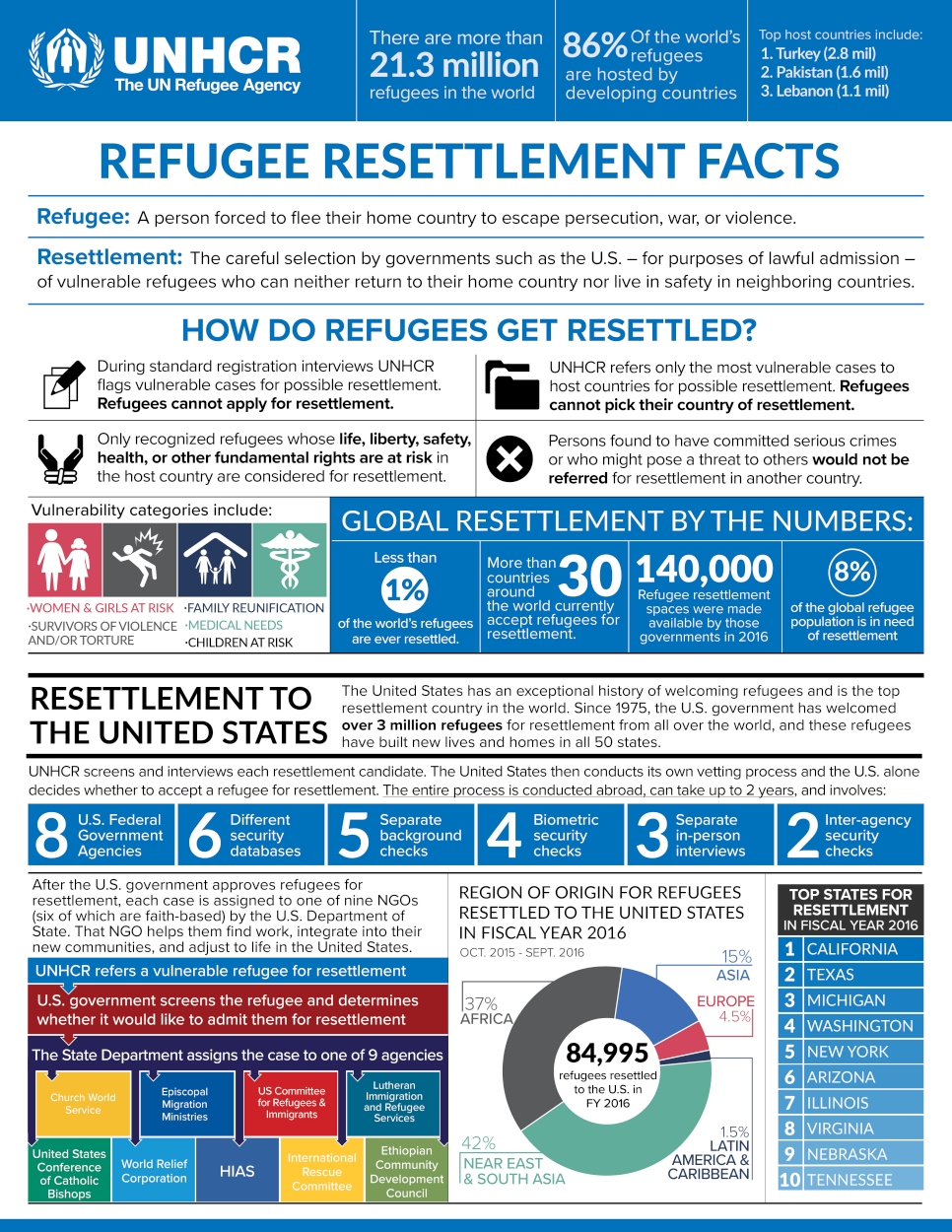

Around the world, 65.6 million people are forcibly displaced, 22.5 million of whom are refugees, and only 189,300 of whom are eventually resettled (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2017). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) defines a refugee as “a person forced to flee their home country to escape persecution, war, or violence” to a neighboring country, or asylum country (2016). Once in the asylum country, refugees are interviewed and identified by the UNHCR to determine which cases are most vulnerable and in need of resettlement. Resettlement is a highly selective and careful process in which a host country’s government lawfully admits vulnerable refugees who have been identified in a State in which they have originally sought protection (UNHCR, 2016). Contrary to popular belief, refugees do not apply for resettlement nor do they pick their country of resettlement, but are instead prioritized based on risk to “life, liberty, safety, health, or other fundamental rights in the host country” (UNHCR, 2011, p. 4). Examples of vulnerable cases include “women and girls at risk, survivors of violence and torture, family reunification, medical needs, and children at risk” (UNHCR, 2011, p.4).

(UNHCR, 2017)

(UNHCR, 2017)

Once a case is identified by the UNHCR, individuals go through a set of security screenings and interviews before the United States even begins its own vetting process to determine whether to admit a family into the resettlement program (UNHCR, 2017). The vetting process occurs abroad and can take as long as 2 years to complete; however, according to the UNHCR, refugees spend an average of 17 years living in exile (2014). The vetting process by the United States government partners with the Department of State Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) Refugee Admissions program, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Refugee Affairs Division of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services in the Department of Homeland Security (UNHCR, 2017). The security screening involves five separate background checks, pulling data from various security databases and works with other agencies to gather all information on the individual and is then assessed for entry by the State Department. If the case is accepted, one of 9 local resettlement agencies will be assigned the case and will work with individuals during the ninety-day resettlement period (UNHCR, 2017). The resettlement process guarantees refugees access to “civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights similar to those enjoyed by nationals,” but they are not able to obtain legal citizenship until 5 years later (UNHCR, 2016).

(UNHCR, 2016)

(UNHCR, 2016)

Upon arrival to the United States, refugees are greeted by caseworkers from one of the nine local resettlement agencies and are taken to their new furnished apartment for their first meal (U.S Department of State [USDOS], 2016). Caseworkers work closely with the newly arrived refugees over the next ninety days to help families establish independence and obtain jobs (USDOS, 2016). Refugees apply for Social Security and Food Stamps, enroll their children in local schools, learn how to access community services, arrange their first medical appointments, and connect with language services and classes (USDOS, 2016).

Refugee Health Screenings

Another mandatory component of the ninety-day resettlement process is obtaining a medical screening and examination within the United States by a designated civil surgeon (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2014). The guidelines for the medical screening are established by the work of the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine in 2006 so that the Department of State (DOS) and the U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services (UCIS) can flag inadmissible refugees due to certain medical conditions (CDC, 2014). This process involves obtaining a person’s medical history and performing a physical exam, screening for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, screening for hepatitis and tuberculosis, testing for intestinal parasites and malaria, and performing an optional mental health screening (CDC, 2014). A person is considered inadmissible if they present with a “communicable disease of public health significance, fail to present documentation of having received vaccination against vaccine-preventable diseases, who have or have had a physical or mental disorder with associated harmful behavior, and who are drug abusers or addicts” (CDC, 2014). These conditions were a direct result of the amendments in 1990 to the Immigration and Nationality Act in the United States and details on inadmissible cases can be found by clicking here and here (CDC, 2014). One recent amendment to the guidelines was the removal of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) from the list of inadmissible conditions in early 2010 (CDC, 2017).

Mental Health Screenings and Differing Perspectives Regarding Best Practices

Although the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine provides explicit guidelines and procedures for assessing refugee health, mental health screenings are not outlined in as much detail and practices vary from state to state (CDC, 2012). Federal funding is provided to agencies that conduct the health screenings, but procedures regarding mental health screenings are independently determined (Barnes, 2001). Variability in practices may also be due to staffing issues and linguistic and cultural barriers present on site (CDC, 2014). The primary concern when performing a mental health assessment is identifying cases in which a particular disorder can lead to harmful behavior and can threaten the safety of others, as first determined prior to arrival in the United States (CDC, 2014). However, diagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) is not a final decision, as a waiver can be completed to connect a refugee with a provider immediately upon arrival to address the particular concern and establish a course of treatment (CDC, 2014).

Prior to arrival in the United States, refugees may be exposed to a variety of factors that put them at risk for developing psychiatric disorders such as exposure to war and violence, oppression, internment in refugee camps, loss of family members, and internal displacement leading to separation (CDC, 2014). Additionally, these pre-migration stressors may be compounded by migration and post-migration stressors including a daily social and material inequality in the host country such as social isolation, discrimination, unemployment, poverty, and uncertain housing conditions (Miller & Rasmussen, 2017). More recently, legislation directed towards refugees and the political climate has contributed to an increase in hate crimes and the development of a hostile environment (Barnes, 2001). Therefore, it is important to recognize that a refugee’s mental health is both impacted by the trauma of conflict and the stress of resettlement and is greatly influenced by the post-migration environment (Miller & Rasmussen, 2017). Inappropriate support or a lack of services offered in the host country may lead to re-traumatization, which has been found to be more predictive of negative health outcomes in refugees (Johnson-Agbakwu, Nizigiyimana, Ramirez, & Hollifield, 2014).

For this reason, it is imperative that appropriate mental health assessments be included in the domestic medical screening, as the mandatory screening is the first encounter refugees have with the local health-care system (CDC, 2014). All refugees are transported to and from their initial medical screening by caseworkers, guaranteeing access to initial care and educational opportunity (CDC, 2014). Although mental health screenings are encouraged, only the Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9) is explicitly recommended for performing depression screenings (CDC, 2014).

The current screening procedure in Tennessee and many other states relies solely on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and assesses the severity of depression through a series of nine questions posed to the patient within minutes (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). However, the limited scope of this procedure fails to assess other mental health disorders such as Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety, both of which are found with increased prevalence in refugee populations (Johnson-Agbakwu, Nizigiyimana, Ramirez, & Hollifield, 2014). Specifically, 30% of refugees are affected by PTSD, which is nearly ten times the national average for US citizens (Polcher & Calloway, 2016). Additionally, the PHQ-9 does not account for presentation of “unexplained somatic symptoms such as headaches, stomachaches, or back pain” in the place of psychiatric symptoms due to cultural barriers and stigma, which may lead to underidentification of mental disorders in refugee populations (CDC, 2014).

The Refugee Health Screening-15 (RHS-15) is a “culturally-responsive screening method for emotional distress,” and has been used in the domestic medical examination for newly arrived refugees in some clinics in Arizona, North Dakota and Germany (Johnson-Agbakwu, Nizigiyimana, Ramirez, & Hollifield, 2014; Kaltenbach, Härdtner, Hermenau, Schauer, & Elbert, 2017, p. 200). The screening is available and has been validated in 15 languages, which overcomes the challenge of administering the PHQ-9 in a culturally-appropriate manner and remains effective throughout the resettlement process (Johnson-Agbakwu, Nizigiyimana, Ramirez, & Hollifield, 2014). The RHS-15 requires minimal training for bi-cultural and bi-lingual staff and only increases patient visits by five to ten minutes, thus proving to be both a time-efficient and effective screening method for anxiety, PTSD, and depression (Johnson-Agbakwu, Nizigiyimana, Ramirez, & Hollifield, 2014).

In a refugee’s primary encounter with the U.S healthcare system, medical professionals are able to begin mental health education and present the RHS-15 in a positive manner so as to encourage treatment and follow up, “lower emotional distress, improve adjustment, and prevent crisis” (Polcher & Calloway, 2016, p. 201). Results from the initial screening identify patients in need of immediate and urgent care, thus reducing the risk for development of poorer health outcomes and enhancing professionals’ understanding of patient mental health needs (Johnson-Agbakwu, Nizigiyimana, Ramirez, & Hollifield, 2014). This initiates a support network and allows for proper referrals to be made early on in the resettlement process. Stigma surrounding mental health is a significant barrier in treating refugee populations; however, patient and practitioner engagement during the initial RHS-15 screening can foster a positive relationship if the procedure is presented as “a tool to assess for emotional distress following resettlement rather than a screening for ‘mental illness’” (Polcher & Calloway, 2016, p. 200). A study assessing the effectiveness of the RHS-15 found that “Seventy-four percent of positive cases accepted treatment services. Of those, 79% engaged in treatment, and 92% continued treatment more than 3 months” (Hollifield, Verbillis-Kolp, Farmer, Toolson, Woldehaimanot, Yamazaki, Holland, St. Clair, & SooHoo, 2013, p. 207).

Perspectives on Refugee Health Outcomes

Another area of debate surrounding refugee health involves the prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCD) over time such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac disease. Though immigrants are thoroughly screened upon arrival for communicable diseases, not much research has been conducted on the prevalence of NCDs in refugee populations upon arrival to the United States. One study investigating this gap in the data found that fifty percent of adult refugees suffer from at least one form of a chronic NCD within the first eight months of arrival in the United States, highlighting the prevalence and severity of the issue (Yun, Hebrank, Graber, Sullivan, Chen, & Gupta, 2012). Furthermore, this finding suggests that “the prevalence of chronic conditions among adult refugees in this cohort may be higher than, or at least comparable to, that of the general US adult population” (Yun et al., 2012, p. 5). This becomes increasingly concerning as these chronic conditions may negatively impact the resettlement process and job success, thus further threatening the economic status of refugees and creating a vicious cycle (Yun et al., 2012).

Although the data from the aforementioned study suggests a desperate need for access to healthcare among refugees in the United States, opposition to federal funding of refugee aid directly threatens refugee well-being as well as the United States economy (Hunter, 2016). A study by Ferweda, Flynn, and Horiuchi (2017) was conducted shortly after President Trump signed an executive order to limit the admission of refugees into the United States in order to understand public opposition to refugee resettlement. Findings from the study indicate that individuals are more likely to be opposed to resettlement if there are not many refugees living within their community and if they have been exposed to negative media coverage of terrorism (Ferweda, Flynn, & Horiuchi, 2017). The authors further predict that these attitudes will become stronger if the current administration continues to pressure to the Department of Homeland Security to allow local governments to opt out of the resettlement process due to possible increased costs (Ferweda, Flynn, & Horiuchi, 2017). The study also suggests that individuals living in communities with a strong refugee presence are less likely to be affected by the media’s depictions of refugees and threatening frames as they are able to develop their own attitudes about their neighbors through personal interactions (Ferweda, Flynn, & Horiuchi, 2017).

Those in support of increased allocation of funds towards refugee resettlement and medical care draw from evidence produced in the 1990s in Germany (Hunter, 2016). During this time period, Germany attempted to lower the numbers of refugees entering the country from the Balkan regions by limiting access to health care (Hunter, 2016). However, findings later indicated that “annual health care costs were substantially higher—on average by 375 Euros per person per year—among migrants with delayed access to health care than those who had immediate access,” suggesting that earlier treatment is most effective and economically efficient (Hunter, 2016, p. 494). Therefore, one might predict similar findings if the high prevalence of NCDs in refugees is not addressed today in the United States.

Connections to Politics of Health

Prior to arrival in the United States, most refugees live in asylum states with high mortality rates and low access to healthcare, contributing to an increased prevalence of communicable diseases and lack of treatment for preventable diseases (Yun et al., 2012). Therefore, it is a widely-held belief that lack of treatment and diagnosis contributes to these prevalence rates in refugees arriving to the United States (Yun et al., 2012). However, this becomes less clear when assessing the prevalence of non-communicable diseases in refugee populations.

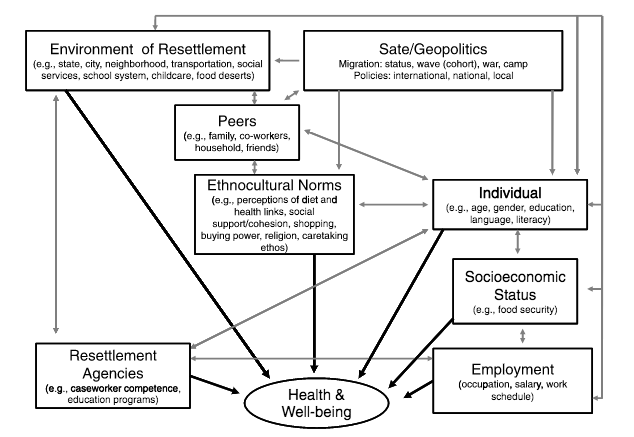

One perspective aligns with the Healthy Immigrant Effect or paradox suggesting that immigrants are “in better health upon arrival in the United States than their American counterparts but that this health advantage erodes over time” (Antecol & Bedard, 2006, p. 357). An ethnographic study by Patil, McGown, Djona Nahayo, and Hadley (2010), replicates this finding among refugees, suggesting that acculturation and daily life in the United States contribute to the “social production of health inequalities” of refugees (p. 141). The study occurred in the urban Midwest and assessed the various factors contributing to poor dietary health and increased prevalence of diabetes among refugee populations resettled in the United States (Patil et al., 2010). Findings from the study suggest that refugees are at an increased risk of suffering from poor diet acculturation due to constraints of low paying jobs, institutional barriers, and sources of knowledge as depicted in Figure 1 below (Patil et al., 2010). Low paying jobs limit the funds and resources families chose to allocate to food as well as their ability to use Food Stamps to pay for food items in specialty stores (Patil et al., 2010). Additionally, transportation limits an individual’s ability to access specialty stores and international markets in order to cook native dishes, resulting in the selection of processed foods and unhealthier items that are appealing to children (Patil et al., 2010). Furthermore, the authors suggest that a history of limited access to food in refugee camps may lead to over-feeding practices among parents, contributing to weight gain in children (Patil et al., 2010). Finally, the researchers suggest that the unequal development of language among children and parents creates tension and “lead to disparate dietary preferences and produce more budgetary strain” (Patil et al., 2010, p. 156).

Figure 1: (Patil et al., 2010).

A refugee’s access to medical care also raises the question of citizenship, as all refugees are granted access to “civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights similar to those enjoyed by nationals,” but are not able to obtain legal citizenship until 5 years later (UNHCR, 2016). Therefore, it is possible that other models of citizenship can be used to better understand refugee status in the United States.

As previously addressed, the stigma surrounding mental health and cultural barriers present in assessing mental health disorders poses challenges for treating refugee populations. The current usage of the PHQ-9 in assessing depression relies on an American standard of normalized behaviors, assessing for daily function and the presence of depressive symptoms (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). This questionnaire does not account for presentation of “unexplained somatic symptoms such as headaches, stomachaches, or back pain” in the place of psychiatric symptoms due to cultural barriers and stigma, which may lead to underidentification of mental disorders in refugee populations (CDC, 2014). Therefore, when asking about standard behaviors relating to depression, refugees may choose not to answer questions honestly due to perceived stigma (Polcher & Calloway, 2016). Relying on this measure enforces a Westernized standard of behavior and only allows for treatment of individuals who subscribe to the “global monoculture of happiness” and identify with a prescribed set of symptoms in order to receive therapy and treatment (Ecks, 2005, p. 244). This relates to Ecks’s concept of pharmaceutical citizenship (2005), as he might argue that the select refugees receiving treatment for depression after being identified through the PHQ-9 are pharmaceutical citizens of the “mainstream middle-class consumer society” (p. 244).

The treatment that refugees receive upon arrival to the United States can also be assessed through the lens of Nguyen’s concept of Therapeutic Citizenship (2005). All incoming refugees receive treatment for preventable diseases and are given basic vaccinations free of cost (CDC, 2014). However, this treatment is mandatory for admission to the United States and although refugees can make strides towards becoming citizens by receiving these treatments, the actions of the United States may be perceived as a “technique used to govern populations and manage individual bodies,” by regulating who is allowed to enter the United States and become a citizen (Nguyen, 2005, p, 126).

Additionally, this humanitarian effort to treat communicable diseases can be interpreted as an expression of biopower by the United States government, as these refugees are in dire need of support from the state. Foucault defined biopower as “forms of power that aim to control, regulate, and monitor a population’s biologic life,” which in this case can be observed by the government determining who is able to enter the United States and what biological treatments they must first receive (Fürher 2015).

References

Antecol, H., & Bedard, K. (2006). Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels?. Demography, 43(2), 337-360.

Barnes, D. M. (2001). Mental health screening in a refugee population: A program report. Journal of Immigrant Health, 3(3), 141-149.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians and Civil Surgeons. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/ti/civil/technical-instructions/civil-surgeons/introduction-background.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Immigrant and Refugee Health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/refugee-guidelines.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Guidelines for Mental Health Screening during the Domestic Medical Examination for Newly Arrived Refugees. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/mental-health-screening-guidelines.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Guidelines for the U.S. Domestic Medical Examination for Newly Arriving Refugees. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/domestic-guidelines.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Medical Examination of Immigrants and Refugees. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/medical-examination.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Medical Screening. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/sexually-transmitted-diseases/medical-screening.html

Ecks, S. (2005). Pharmaceutical citizenship: Antidepressant marketing and the promise of demarginalization in India. Anthropology & Medicine, 12(3), 239-254.

Ferwerda, J., Flynn, D. J., & Horiuchi, Y. (2017). Explaining opposition to refugee resettlement: The role of NIMBYism and perceived threats. Science advances, 3(9), e1700812.

Führer, Amand. “Statistics and sovereignty: the workings of biopower and epidemoiology.” Global Health Action 8 (2015): 1-2.

Hollifield, M., Verbillis-Kolp, S., Farmer, B., Toolson, E. C., Woldehaimanot, T., Yamazaki, J., … & SooHoo, J. (2013). The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15): development and validation of an instrument for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in refugees. General hospital psychiatry, 35(2), 202-209.

Hunter, P. (2016). The refugee crisis challenges national health care systems. EMBO reports, 17(4), 492-495.

Johnson-Agbakwu, C. E., Allen, J., Nizigiyimana, J. F., Ramirez, G., & Hollifield, M. (2014). Mental health screening among newly-arrived refugees seeking routine obstetric and gynecologic care. Psychological services, 11(4), 470.

Kaltenbach, E., Härdtner, E., Hermenau, K., Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2017). Efficient identification of mental health problems in refugees in Germany: the Refugee Health Screener. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup2), 1389205.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The phq‐9. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(9), 606-613.

Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2017). The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: an ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences, 26(2), 129-138.

Nguyen, V. K. (2005). Antiretroviral globalism, biopolitics, and therapeutic citizenship (pp. 124-144). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Patil, C. L., McGown, M., Nahayo, P. D., & Hadley, C. (2010). Forced migration: Complexities in food and health for refugees resettled in the United States. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 34(1), 141-160.

Polcher, K., & Calloway, S. (2016). Addressing the need for mental health screening of newly resettled refugees: a pilot project. Journal of primary care & community health, 7(3), 199-203.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNHCR Resettlement Handbook, 2011, July 2011, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4ecb973c2.html [accessed 19 November 2017]

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2016). Information on UNHCR Resettlement. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/information-on-unhcr-resettlement.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2016). Resettlement in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/resettlement-in-the-united-states.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2017). Figures at a Glance. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html

U.S Department of State. (2016). U.S Refugee Admissions Program. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/j/prm/ra/admissions/index.htm

Yun, K., Hebrank, K., Graber, L. K., Sullivan, M. C., Chen, I., & Gupta, J. (2012). High prevalence of chronic non-communicable conditions among adult refugees: implications for practice and policy. Journal of community health, 37(5), 1110-1118.

« Back to Glossary Index