Definition of Term and Background:

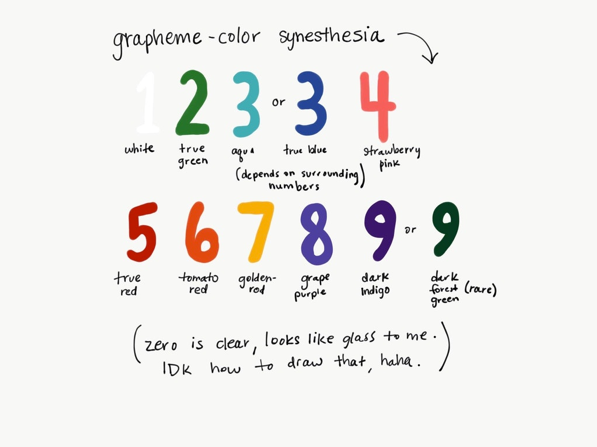

Synesthesia (also spelled Synaesthesia) is a phenomenon in which when one sense is stimulated, other senses are stimulated as well. There are many ways in which people can have synesthesia because it can involve any of the senses. The most common type is called grapheme-color synesthesia, which means that someone associates colors with letters and/or numbers (i.e. A is red). Some people only associate the color with the letter while others perceive the letter as being red, no matter which color it actually is. Some other examples of the coupling of the senses is seeing colors when one hears music or associated colors with certain food (i.e. beef is dark blue). (Robertson & Sagiv, 2005)

Figure 1. Depiction of grapheme-color synesthesia (Casandraonline, Reddit)

Different types of Synesthetes:

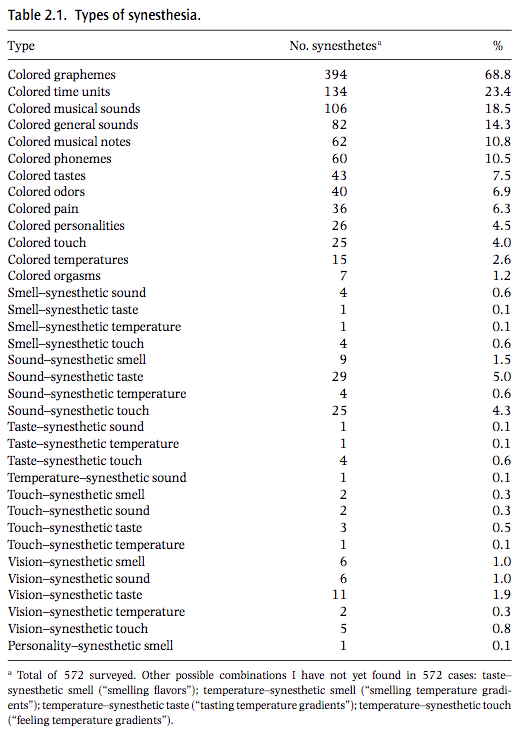

Figure 2. Examples of types of synesthesia (Robertson & Sagiv, 2005)

While the list above is not fully exhaustive of every type of synesthesia someone could have, it is a fairly inclusive list developed by Sean Day in his research about synesthesia. This list was published in a book in 2005, so it is probable that the numbers have changed, but I am including this to demonstrate the variability in synesthesia. This variability makes it more difficult to have a set way of studying this phenomenon and so most researchers have to choose which type of synesthesia to study.

Historical Context:

Synesthesia was first studied by Sir Francis Galton in 1880. Galton was not a synesthete, but his friend was, and it led him to study the phenomenon. He concluded that synesthesia occurred in about “1 out of every 30 adult males, or 15 females” (Galton, 1880). Other psychologists since then have estimated different numbers of prevalence, as low as 1 in 25,000 (Cytowic, 1989). The most cited number today, though, is 1 in 2000 (Baron-Cohen et al, 1996). Early research led Galton to believe that synesthesia is a familial trait and that it is more common in females than males (Galton, 1880). Baron-Cohen et al. (1996) supported this theory in their research as well. Research in synesthesia was popular at the beginning of the 20th century but faded out by the 1940s due to incredibility in the studies. Research began again in the 1980s (Baron-Cohen et al., 1996).

Perspectives/Controversy:

The debate about whether or not synesthesia is even real has driven most of the research about synesthesia. People who do not experience synesthesia may have a difficult time believing that it exists. In the 1940s, studies about synesthesia essentially vanished because “introspection had become an unrespectable method of data collection in experimental psychology, and there appeared to be no objective way of validating that synaesthesia was actually occurring, over and above the self-report data from the subjects themselves” (Baron-Cohen et al., 1996). Since there was no standardized test to prove that synesthesia existed, researchers found no point in continuing the research.

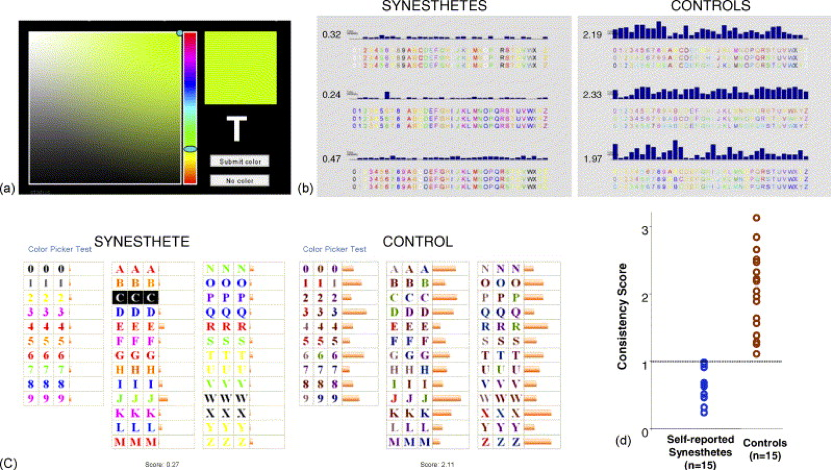

Since then, more research has been developed about synesthesia and more tests have been created to prove that synesthesia exists. The first standardized test that became widely accessible was in 2007 at www.synesthete.org. This site includes a questionnaire about which symptoms of synesthesia the individual has. Then there is a test for the specific type. For example, if someone has grapheme-color synesthesia, they will be asked to give each letter a color three different times to see whether it is the same (Eagleman et al., 2007). In Eagleman et al.’s study (2007) they tested synesthetes versus a control group of non-synesthetes to test the validity of this test.

Figure 3: results from Eagleman et al.’s study (2007).

In the results, we see that synesthetes were more consistent throughout the trials while the control group had more variability with each trail. This demonstrates that synesthesia is, in fact, real. However, this is just one example of the testing that researchers have done to test for synesthesia.

Relation to Politics of Health:

Synesthesia is related to politics of health through the medicalization of synesthesia and the lack of widespread scientific knowledge about it. Synesthetes tend to not have issues from their synesthesia that negatively impact their lives. However, knowledge about synesthesia is not very common, especially in developing countries, and some synesthetes are institutionalized as a result of this phenomenon. These are excerpts from Sean Day’s section of the book Synesthesia: Perspectives from Cognitive Neuroscience.

In the past 6 years, I have also received urgent e-mail messages from synesthetes in Chile, Peru, and Italy. In each of these cases, the synesthete had sought out doctors to get more information about their synesthesia, only to get caught in a complex web where one or more doctors, plus various family members, wanted to institutionalize them, or at least perform a series of quite potentially harmful tests involving drugs (19).

This excerpt shows real life examples of doctors not understanding what synesthesia is, and automatically medicalizing it because it is not the norm.

Synesthesia is not considered a problem in most cases. However, lack of knowledge about synesthesia—within the medical and scientific community, and, more broadly, among the general public—is considered a major problem by the synesthete community. Synesthetes do not need a cure for synesthesia. Rather, we need and want non-synesthete experts, family members, and concerned others to be informed about the occurrence and nature of our experiences so that it stops being thought of as an aberration, but rather as a normal variant of perception. Together, we all need to work at finding ways to get rid of biases, misconceptions, pseudoscientific misinformation, dogmatism, and intolerance, so that far many more synesthetes can finally feel a sense of relief and acceptance (31).

Sean Day is also a synesthete, and this excerpt summarizes his feelings about synesthesia in relation to the general public. Synesthetes do not need their condition to be medicalized, rather, they want their condition to be recognized.

References:

Baron-Cohen, Simon, Lucy Burt, Fiona Smith-Laittan, John Harrison, and Patrick Bolton. “Synaesthesia: Prevalence and Familiality.” Perception 25, no. 9 (September 1, 1996): 1073-079. doi:10.1068/p251073.

Casandraonline. “My Grapheme-color Synesthesia • R/Synesthesia.” Reddit. August 15, 2017. Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.reddit.com/r/Synesthesia/comments/6twc1e/my_graphemecolor_synesthesia/.

Cytowic, Richard E. “Theories of Synesthesia: A Review and a New Proposal.” Springer Series in Neuropsychology Synesthesia, 1989, 61-90. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3542-2_3.

Eagleman, David M., Arielle D. Kagan, Stephanie S. Nelson, Deepak Sagaram, and Anand K. Sarma. “A Standardized Test Battery for the Study of Synesthesia.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods 159, no. 1 (January 15, 2007): 139-45. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.07.012.

Galton, Francis. “Visualised Numerals.” The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 10 (1881): 85-102. doi:10.2307/2841651.

Robertson, Lynn C., and Noam Sagiv. Synesthesia: Perspectives from Cognitive Neuroscience. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

« Back to Glossary Index