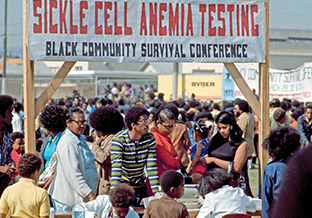

Free sickle cell anemia testing at the Black Community Survival Conference in Mar-Apr 1972.

Here is a link to a short video of the Black Community Survival Conference in 1972, taken from the San Francisco Bay Area Archives. https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/190201

Background: The Black Panther Party and Health Activism

The Black Panther Party (BPP) was an Afrocentric, leftist organization founded in 1966 in Oakland, CA. The prolific movement used Black nationalist rhetoric in order to provoke the US Government into making racially-sensitive policies aimed towards the greater Black community.[1] While originally created in order to hold local police accountable for their acts of physical brutality, the BPP quickly evolved into a multifaceted activist organization with headquarters all over the world. Led by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, the BPP created a Ten-Point Program in May 1967 that outlined its short- and long-term goals. Newton and Seale aimed to achieve de facto freedom for the Black community, meaning: full employment, exemption from the military, decent housing, education, physical safety from police brutality and freedom of those currently held in local, state and federal prisons. To the BPP, the government’s inactive stance towards Black Americans was reinforced and exacerbated by the “[Capitalist robbery] of the Black Community”.[2]

The Black Panther Party used multiple vehicles to transport their message throughout the country and the world. One of the most notable ways they did so was through health and healthcare activism. In March 1972, the BPP held the first Black Community Survival Conference in Oakland, CA, where they distributed food, registered people to vote and took blood tests for sickle cell anemia.[3] Thousands of people attended, attracting substantial media attention and ultimately many new, Black members who were eager to unify as one community. This was the first of many acts of social activism that the BPP instigated; Newton and Seale also created the Free Breakfast For Children program, sponsored classes on health and economics, taught lessons on self-defense and first aid, created an “emergency-response ambulance program” and a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center.[4] These programs attempted to keep the Black community healthy, informed and safe—feats that the US government had not achieved in the eyes of the BPP. As a result, the BPP’s mantra became “serve the people, body and soul”.[5]

While the Free Breakfast For Children program garnered widespread acknowledgement for its massive attendance and its facilitation of the BPP’s core values, the most notable health activism the BPP conducted was its fight for awareness, prevention and treatment for sickle-cell anemia (SCA). A disease that affects the size and shape of red blood cells in the body, SCA is most commonly (but not exclusively) found among people of African descent. As such, the Black Panther Party coined SCA as a ‘Black Disease’, citing the lack of publicly-funded research on it as a racialized issue.[6] This became one of the Party’s main avenues for social activism. The BPP proceeded to create medical clinics called People’s Free Medical Centers all over the country in order to increase access to healthcare and sickle-cell testing[7] for underprivileged Black communities, all the while providing them a strong political education.[8] They continued to fight for these causes until the Nixon Administration finally answered their wishes for federal regulation of SCA in 1971. This action ironically took the wind out of BPP’s anti-government sails, eventually leading to the Party’s expiration in 1982.

Controversy

However, it didn’t take long for the BPP and their proactive defense of Black lives to come under scrutiny. In the fall of 1967, Huey Newton allegedly murdered a white police officer, prompting FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to label the Party as a “black nationalist hate group”. In the following years, Hoover made it his mission to delegitimize the Black Panther Party by weakening its leadership and ideological strength. He created a government program called COINTELPRO in order to prevent Black Americans from organizing during the 1960’s, ultimately authorizing Hoover to shut down the BPP’s medical clinics across the nation.[9] Had Hoover and COINTELPRO not shut down these clinics, the BPP would have tested an estimated 1 million people for sickle-cell disease by 1973.[10]

Hoover also targeted Nation of Islam, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and Martin Luther King Jr. His ultimate goal was to pit Black activists together in order to destabilize them in one swift movement.[11] Hoover’s crusade against the Black Panthers, however, was particularly controversial. COINTELPRO used “surveillance, infiltration, perjury and police harassment” in order to defeat ‘the Black anarchist organization’ that was responsible for crimes against white people and officers of the law.[12]

Many did not share Hoover’s sentiment towards the Black Panther movement. In her novel, Body and Soul, Dr. Alondra Nelson writes that “the Party’s focus on healthcare was both practical and ideological”.[13] Nelson was among many who believed that the BPP was simply trying to reduce the healthcare inequity that was spurred by racist institutions (the government, schools, Big Pharma, hospitals, etc.) by providing free health resources and prevention tools to underserved Black communities. In Nelson’s view, the BPP simply used sickle-cell disease as a vehicle for their message: racially-sensitive healthcare is a right, not a privilege.[14]

Historical Context

The Black Panthers’ SCA activism raised awareness about Black bodies, expanded community healthcare infrastructure (to include sickle cell prevention) and called attention to the government’s blunders.[15]

But while the BPP strived earnestly to maintain these efforts, they faced racial barriers to their continued success. Regardless of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), de facto equality was still largely absent from American culture during the 1960’s.[16] Much discrimination and prejudice towards Black people occurred on a regular basis, barring The Black Panthers and other activist organizations from achieving their goals of equality. But while Black leaders like MLK Jr. preached nonviolence and vocal protests, leaders of the BPP and the Nation of Islam (Malcom X) resorted to violent means, if necessary.[17] This often obfuscated the BPP’s core values and goals, often acting counterintuitively against them.

Nevertheless, the Black Panther Party’s goals of uplifting Black America overshadowed any of its penchant for violence, even if the entities became entangled from time to time. By racializing sickle-cell anemia and contextualizing it as a Black Problem in need of federally-mandated solutions, the BPP ushered in a new era of health activism in the United States where anyone could petition the government to address hot button issues of their choice.

One health activist program that arose as a result of the BPP’s boundary-pushing work is the HIV/AIDS movement in the 1980’s. This is an important, parallel context to the BPP’s work with SCA; like the Panthers, the LGBT community claimed HIV/AIDS as their own and used it as a vehicle for their own ideological goals. While HIV is not solely a gay disease, activists used it as a way to discuss LGBT(QIA) rights, institutional pathways of inequity, problematic marriage laws and lack of access to healthcare resources. They uplifted the LGBT community, and used HIV to become their own agents of change and equality, much like the Black Panthers did with SCA. Both the BPP and LGBT activists strove to get biological citizenship for their communities; recognition from the government in the form of sensitive health policies and resources would have opened doors for racial and gender equality.[18] Because we embody the environments, opportunities and policies in place to regulate us, racialized and gender-sensitive health policy would have also lead to healthier minority bodies in the US. This was the fundamental goal of both the Black Panthers and LGBT activists in the mid-20th century.

Politics of Health

The Black Panthers’ emphasis on health activism is directly related to the politics of health. They willingly politicized sickle cell anemia in order to advocate rigorously on behalf of the Black community. They used health as a mediating tactic through their ideologically reinforced health education, genetic screening for a racialized disease (SCA), food programs emphasizing Black history, systematic oppression, and barriers to access for Black Americans. They made a seemingly ‘invisible’ disease like sickle-cell anemia ‘visible’ through adamant activism, free clinics, and robust education programs, attempting to give Black Americans biological citizenship in the United States.[19] They flipped the script on racialized political tactics by racializing sickle-cell anemia themselves. This forced the government to see SCA through Black lenses, to heed any institutional barriers in place costing them peace, racial equality and money and make a change. Nixon’s 1971 fundraising efforts for SCA research was a great first step to institutional and biological recognition of Black bodies. However, we still do not have a reliable cure for sickle-cell anemia, rendering it a political health problem today.

Bibliography

Alkebulan, Paul. Survival pending revolution: the history of the Black Panther Party. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Austin, Curtis J. Up against the wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006.

Bader, Elanor J. “Black Panthers’ Fight For Free Health Care Documented in New Book.” Truthout: News Analysis. October 26, 2013. Accessed January 26, 2017. http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/19603-new-book-explores-the-black-panther-party-fight-for-free-health-care.

Black Community Survival Conference II. San Francisco Bay Area Archive. September 27, 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017. https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/190201.

Bloom, Joshua, and Waldo E. Martin. Black against empire: the history and politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Fullilove, Robert. “The Black Panther Party Stands for Health.” The Black Panther Party Stands for Health | Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. February 23, 2016. Accessed January 26, 2017. https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/black-panther-party-stands-health.

Hazen, Don. “The Side of the Black Panthers That’s Been Virtually Ignored: Their Fight for Healthcare Justice.” Alternet. December 21, 2011. Accessed January 26, 2017. http://www.alternet.org/story/153527/the_side_of_the_black_panthers_that%27s_been_virtually_ignored%3A_their_fight_for_healthcare_justice.

Lazerow, Jama, and Yohuru R. Williams. In search of the Black Panther Party: new perspectives on a revolutionary movement. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Nelson, Alondra. Body and soul: the Black Panther Party and the fight against medical discrimination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Petryna, Adriana. “Biological Citizenship: The Science and Politics of Chernobyl-Exposed Populations.” Osiris, 2nd Series, 19 (2004): 250-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3655243.

Westneat, Danny. “Reunion of Black Panthers stirs memories of aggression, activism.” Tribune Business News, June 2, 2004. Accessed January 26, 2017. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-117788029.html?refid=easy_hf.

[1] Paul Alkebulan, “Survival pending revolution: the history of the Black Panther Party”, (Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 2007), 25-40.

[2] Ibid., 25-40.

[3] “Black Community Survival Conference II.”, (San Francisco Bay Area Archive, 2011).

[4] Danny Westneat, “Reunion of Black Panthers stirs memories of aggression, activism.” (Tribune Business News, 2004), 1.

[5] Alondra Nelson, Body and soul: the Black Panther Party and the fight against medical discrimination, (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 115-152.

[6] Ibid., 115.

[7] Panther clinics also provided basic health services such as: “testing for high blood pressure, lead poisoning, tuberculosis, and diabetes; cancer detection screenings; physical exams; treatments for colds and flu; and immunization against polio, measles, rubella, and diphtheria…[as well as] well-baby services, pediatrics and gynecology exams”. See

Elenor J. Bader, “Black Panthers’ Fight For Free Health Care Documented in New Book.” (Truthout: News Analysis, 2013), 1.

[8] Ibid., 1.

[9] Westneat, “Reunion of Black Panthers stirs memories of aggression, activism.”, 1.

[10] Nelson, Body and soul, 115.

[11] Jama Lazerow and Yohuru R. Williams. In search of the Black Panther Party: new perspectives on a revolutionary movement. (Durham, Duke University Press, 2006.), 55.

[12] Ibid., 57.

[13] Don Hazen, “The Side of the Black Panthers That’s Been Virtually Ignored: Their Fight for Healthcare Justice.”, (Alternet, 2011), 1; Nelson, Body and soul, 120.

[14] Nelson, Body and soul, 118.

[15] Ibid., 126.

[16] Robert Fullilove, “The Black Panther Party Stands for Health.”, (New York, Columbia University Press, 2016), 1.

[17] Curtis J. Austin, Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. (Fayettvile, University of Arkansas Press, 2006), 14.

[18] Petryna, Adriana. “Biological Citizenship: The Science and Politics of Chernobyl-Exposed Populations.” Osiris, 2nd Series, 19 (2004): 250-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3655243.

[19] Nelson, Body and soul, 120.

« Back to Glossary Index