Nicole Hefner

Professor Callahan-Kapoor

Politics of Health

April 6, 2017

The Food and Drug Administration

Definition and Background

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is a regulatory agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is responsible for promoting public health by regulating and supervising food safety, tobacco products, dietary supplements, medicine, medical devices, and other products (“What Does the FDA Do,” 2017). It is the oldest comprehensive consumer protection agency in the U.S. federal government, having been established in 1906 with the signing of the Food and Drug Act by President Theodore Roosevelt (“History,” 2015). As of 2014, the FDA had a budget of $4.4 billion and employed 15,000 individuals, including chemists, pharmacologists, physicians, microbiologists, veterinarians, lawyers, and others (Swann, 2014). Over $1 trillion worth of consumer goods – more than 25% of yearly consumer expenditures in the United States – is regulated by the FDA. The FDA received its regulatory authority from the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act enacted in 1938, and today it regulates both domestic and imported goods. Currently, the FDA is headquartered in Maryland, but 1/3 of the employees are based in Washington, D.C.; additionally, there are 223 field offices and 13 laboratories located throughout the country and abroad (“What Does the FDA Do,” 2017).

The responsibilities of the FDA extend to all fifty states as well as to Washington D.C. and U.S. territories including Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa. The FDA is made up of the Office of the Commissioner and four core directorates: medical products and tobacco, food and veterinary medicine, global regulations and policy, and operations. These four sectors divide up the responsibilities of the FDA which include, but are not limited to, protecting public health by assuring that foods are safe and properly labeled, assuring that drugs, vaccines, and medical devices are safe and effective, and protecting the population from radiation exposure (“FDA Basics – FDA Fundamentals,” 2015). The degree to which the FDA can regulate a certain product depends on the product itself. Nearly every aspect of prescription drugs (their testing, manufacturing, labeling, efficacy, and safety) is regulated by the FDA, while only the safety and labeling of cosmetic products is FDA-regulated. The FDA has been charged with predicting issues before they arise, which requires a huge labor force, constant testing, and the participation of manufacturers in oversight programs. Medications must undergo extensive testing before being marketed, and subsequent monitoring is required after they are released (“What Does the FDA Do,” 2017). Agency scientists are in charge of evaluating applications for new drugs, medical devices, and additives before they are approved or rejected (Swann, 2014). Foods and cosmetics, however, are not typically pre-approved, but they are inspected and recalled at a later time if problems are discovered. The FDA’s mission is to promote the health of the public and to help deliver safe and effective treatments. If industries are non-compliant with the rules that the FDA sets in place to achieve its mission, they may face fines, seizure of goods, civil liabilities, or criminal charges (“What Does the FDA Do,” 2017).

Controversy/Perspectives

The FDA’s primary job is to evaluate the safety of food and drugs and to approve new drugs for marketing. This is a demanding and complex task, and there have been many controversies about the way in which the FDA goes about its approval and regulation processes. Some feel that historically the FDA has taken far too long to take action when dangerous chemicals such as mercury or acrylamide have been found in food. They claim that the FDA is nonresponsive to outbreaks of bacteria in food, and that salmonella outbreaks in eggs, for example, could have been eradicated years ago if the FDA did not keep delaying the institution of on-farm regulations (“FDA Fails to Protect Americans from Dangerous Drugs and Unsafe Foods,” 2006). At the other extreme are those who criticize the FDA for overregulating food and drugs, often citing the Kefauver-Harris Amendments as the root of this problem. In 1962, the Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics Act of 1938 expanded the power of the FDA and added a proof-of-efficacy requirement. Because it takes much longer to prove the effectiveness and not just the safety of a drug, time constraints on the approval process were removed. As a result of the Kefauver-Harris Amendments, the FDA took much longer to approve drugs than previously, and there was a significant drop in the number of drugs approved per year after 1962. Critics complain that the FDA is overregulating new drugs, and that the subsequent delay and reduction in approval of drugs is costing people their lives (“Theory, Evidence, and Examples of FDA Harm,” 2016).

When the FDA was criticized in the 1990s for taking too long to approve drugs, Congress passed legislation allowing industries to reimburse the FDA for reviews in order to incentivize them to speed up their evaluations (“FDA History – Part V,” 2009). However, soon after the passage of that legislation, a crisis developed in 2004 with the FDA-approved drug Vioxx, which was found to increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes. The FDA was then criticized for approving medicines too easily and being too slow to issue warnings (Harris, 2008). Clearly, the FDA faces critiques from both sides of the argument regarding whether they are overregulating or underregulating drugs.

Today it can still be difficult to determine if a risk alert is from the FDA or not. For example, pharmacists pass out drug information sheets with prescriptions that appear to be official government papers. However, the FDA does not regulate or oversee those sheets at all, and erroneous information has been discovered on them. The FDA also does not oversee dietary supplements, and it only takes action if the supplements are shown to be unsafe. Therefore, any references to the FDA on dietary supplements do not actually mean that the FDA has approved them. For drugs, the FDA demands that manufacturers provide proof that the drugs are safe and effective, yet there are still exceptions. Some prescription medications today have been around since before the creation of the FDA and were never formally approved. The FDA still intends to eventually evaluate all of these drugs, but for now there continue to be unapproved prescription drugs on the market (Harris, 2008).

Historical/Topical Context

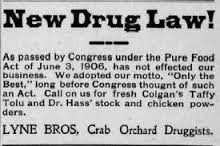

The first vestiges of the FDA date back to Lewis Caleb Beck in the Patent Office of the United States federal government who, in 1848, was given the task of performing chemical analyses of agricultural products (“History,” 2015). This spurred the creation of a division of chemistry in the federal government, which later became the Bureau of Chemistry in 1901. The modern era of the FDA, however, started in 1906, with the passage of the Pure Food and Drugs Act (Swann, 2014). For 27 years, Congress had blocked proposals for federal food and drug regulations. This act ended that impasse and represented a shift from distributive to regulatory functions of the federal government. In the latter half of the 19th century, technological innovations opened up new markets for the food, beverage, and drug industries, increasing competition and driving down prices. But inconsistencies in state laws made operating nationally very difficult. Products that would sell in one state sometimes did not conform to the standards of other states, and as a result, companies would need to produce multiple versions of a product. In addition, reports of food, beverages, and drugs containing adulterated products became so frequent around 1900 that Congress finally took a more active role in the pure food and drug movement. In 1906, Congress acknowledged the existing threats to public health, and political resistance to federal legislation on food and drug control finally dissipated (Barkan, 1985). The Pure Food and Drug Act was signed by President Theodore Roosevelt on June 30, 1906; it revolutionized the food and drug industries by forming the FDA as a consumer protection agency (Mulvaney, 2010).

The Pure Food and Drug Act prohibited the interstate transport of unlawful food and drugs as well as the addition of ingredients to food that posed any health hazard. Drugs that were defined by a certain standard could not be sold in any other condition unless clearly stated on the label, and all food and drugs had to accurately state the amounts of certain dangerous ingredients such as alcohol, heroin, and cocaine that they contained (“FDA History – Part I,” 2009). The act was passed in hopes of providing better regulation for drugs. One common occurrence prior to this time was that medicines did not cure the conditions that they claimed to, but instead they simply contained narcotics that numbed consumers so that they did not feel the effects of their illness as strongly (Mulvaney, 2010).

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, bringing cosmetics and medical devices under FDA control and requiring that drugs be labeled with directions for safe usage (“FDA History – Part II,” 2012). This act increased federal regulation by mandating pre-market approval of all drugs and giving the FDA authority to inspect factories and establish standards for food, cosmetics, and therapeutic devices. It is considered to be the foundational core of the FDA, as it provided the FDA with the regulatory authority most central to their current role.

The FDA has undergone a series of transitions since that time. In 1940, the FDA was transferred to the Federal Security Agency, which later became the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Then, in 1988, the Food and Drug Administration Act transferred the FDA to the Department of Health and Human Services where it would be led by a commissioner appointed by the president. Today, the FDA still works toward its same core mission of public health (Mulvaney, 2010). A recent event involving the FDA was the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act signed by President Obama on 4 January 2011. This sweeping reform ensured that the United States’ food supply was healthy by enacting a shift from responding to contamination events to preventing them (O).

How it relates to politics of health

The United States Food and Drug Administration is related to the topic of institutions through the concept of the political body. The FDA has rules and standards applied to the nation as a whole for its own well-being, as if it were one singular body that needs to be taken care of. It is the politicians of our country, not the citizens and laypeople, who make decisions regarding how the FDA regulates the food and drugs marketed throughout the nation. The FDA falls primarily under the political body as opposed to the individual or social body because its decisions may not affect each individual person or symbolize relationships in nature and society, but as a U.S. federal executive department, it will always be an artifact of political control (Scheper-Hughes and Lock, 1987).

The political body encompasses national institutions that regulate how we must act; this is exactly what the FDA does. It has certain responsibilities to the American public, which include protecting our health by regulating the actions of industries. When industries do not comply with the FDA’s standards, the FDA has the authority as a federal institution to punish those industries through fines or litigation (“What Does the FDA Do,” 2017). The FDA has structures and rules for approval and rejection of medications and foods, is organized and works toward a concerted effort of protecting public health, and is tied to government funding. These are all key components of an institution. Through the institution of the FDA, the United States’ political body serves public health through regulation and supervision of all food and drugs marketed to the American people.

Bibliography

Barkan, I. D. “Industry invites regulation: the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.” American Journal of Public Health 75, no. 1 (1985): 18-26. Accessed April 5, 2017. doi:10.2105/ajph.75.1.18.

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. “FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA).” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page. 2017. Accessed April 05, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/food/guidanceregulation/fsma/

“FDA Basics – FDA Fundamentals.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page. 2015. Accessed April 05, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/aboutfda/transparency/basics/ucm192695.htm

“FDA Fails to Protect Americans from Dangerous Drugs and Unsafe Foods.” Center for Science in the Public Interest. 2006. Accessed April 04, 2017. https://cspinet.org/new/200606271.html

“FDA History – Part I.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page. 2009. Accessed April 05, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/Origin/ucm054819.htm

“FDA History – Part II.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page. 2012. Accessed April 04, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/Origin/ucm054826.htm

“FDA History – Part V.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page. 2009. Accessed April 05, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/Origin/ucm125632.htm

Harris, Gardiner. “What’s Behind an F.D.A. Stamp?” The New York Times. September 29, 2008. Accessed April 04, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/30/health/policy/30fda.html

“History.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page. 2015. Accessed April 05, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/default.htm

Mulvaney, Dustin. Green Food : An A-to-Z Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2010. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed April 5, 2017).

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Margaret M. Lock. “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, 1, no. 1 (1987): 6-41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/648769.

Swann, John P. “FDA’s Origin & Functions – FDA’s Origin.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Page. 2014. Accessed April 05, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/Origin/ucm124403.htm

“Theory, Evidence, and Examples of FDA Harm.” FDAReview.org: a project of the Independent Institute. 2015. Accessed April 05, 2017. http://www.fdareview.org/05_harm.php

“What Does the FDA Do.” HG.org: Legal Resources. 2017. Accessed April 05, 2017. https://www.hg.org/article.asp?id=35057

« Back to Glossary Index