TIRC

Definition/Background

In 1954, the Tobacco Industry Research Committee, or TIRC, was established by a coalition of fourteen major tobacco companies to investigate the consequence of smoking on health (Cigarette Century, 251). It was founded as a subset of the Tobacco Institute trade association, which the public—including newspapers, activist groups, and eventually the U.S. legal system—has accused of obfuscation of scientific knowledge on health concerns, questionable public relations tactics like marketing to children and young adults, lobbying to influence political restrictions in their favor, opposing tobacco control measures, and letting industrial growth take precedence over the public welfare (Saloojee et al., 2000). Litigation has since made public much of the Tobacco Institute’s documentation, seeming to shed light on its alleged collusion in governmental and scientific affairs. As a result, in 1998, the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement dissolved the Tobacco Institute and the TIRC, while imposing various restrictions, financial provisions, and multi-billion-dollar settlement claims (Master Settlement Agreement).

Context

A.M. Brandt, a medical researcher focusing on the socio-ethical history of health, notes in his work on tobacco and the tobacco industry, “The cigarette had drawn fire from critics ever since its popular introduction in the nineteenth century…The medical literature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is replete with testimony to the multiple perils of tobacco. Nonetheless, the cigarette had largely trumped these objections by the 1930s as it became ubiquitous. Smoking came to be considered a behavior of medical discretion…” (Cigarette Century, 3). Clearly, a hospitable cultural context—one that highly approved of individual choice in matters of personal risk, and was readily susceptible to innovative marketing—proved vital for the tobacco economy, and would seem an inviting, distortable angle by which the Tobacco Institute could salvage their market. However, critical investigation of tobacco would only continue. In June of 1954, the American Cancer Society released findings that indicated a significant health disparity in smokers and non-smokers aged 50 to 70 (Brawley et al., 6). This was also following a recent drop in domestic sale of cigarettes, according to a 1953 survey (3). Thus, Brandt concludes, the 20th century scientific milieu—characterized by expansion and consolidation of the scientific method, a probative tool highly conducive to critical inquiry—coupled with a slacking grip of the tobacco industry on public credibility (as evidenced by the declining consumer base) likely shocked the major industrial players into forming the Tobacco Institute coalition, as the members’ profits were broadly threatened by incisive scientific study which painted tobacco in a negative light (Inventing Conflicts of Interest, 2012). Brandt adds, the postwar nuclear age also played into the industry’s stratagem; as he says, “science was in high esteem” and so the TIRC had to balance public image with its aims to subvert and condemn the looming threat of scientific knowledge (Inventing Conflicts of Interest, 2012). As a result, the TIRC would proliferate their own studies that discredited any link between smoking and cancer (Brawley et al., 6). The back-and-forth claims between the TIRC and independent studies continued, fluctuating tobacco sales and the public opinion on cigarette use, until the TIRC was effectively dismantled by the Master Settlement Agreement (Cigarette Century, 2009). Brandt continues, “By the early 1990s, smoking rates—spurred by powerful shifts in the social meaning of cigarette use—would dip in the United States to approximately 25 percent, the lowest rates since the 1920s” (7). Thus, a reversal of the cultural climate can have an opposite effect on public industry, as the increasing awareness of adverse effects of smoking as well as tightened tobacco regulation devastated the prospering corporate entity. As a result, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop says, “over 750,000 lives have been saved” (Cigarette Century, 7). Avoiding not only a danger to scientific credibility, the dismantling of the TIRC has thus served to mitigate a serious threat to public health.

Population of Smokers in the U.S. Note the high smoker retention during TIRC establishment around ’53 and the drastic drop around the Master Settlement Agreement in ‘98 – Stackexchange.com

Perspectives

TIRC research effectively split public confidence not only in smoking, but also in scientific knowledge itself. In support of industry funded studies and the innocuousness of tobacco, Dr. C. C. Little was the scientific director of the TIRC and also an adamant research skeptic; naturally, he doubted the probative force of scientific analysis of the time relating to smoking as hazardous to health, as he says to a Wall Street Journal reporter, “The present dramatic situation emphasizes the need for greatly extended basic research” (Wall Street Journal, 1954). In the same article, he also appealed to an attitude of cooperation between the TIRC and ACS, as demonstrated by his access to preliminary findings prior to their public release. At first blush, it would seem that there remained genuine skeptics to the carcinogenic quality of tobacco—considering TIRC publication and mid-1900s smoker retention—following the preliminary flood of scientific suspicion by “the British Medical Research Council; the American Heart Association; the Joint Tuberculosis Council of Great Britain; the Canadian Department of National Health and Welfare; the cancer societies of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Netherlands; and the American Cancer Society” in the 1950s (Brawley et al., 6). However, even after Surgeon General Luther Terry announced the unequivocal link between smoking and lung cancer in 1966, the tobacco industry insisted on the lack of categorical evidence for the next three decades (Cigarette Century, 2009). This issue raises questions of conflicting interest—whether research should accept industry funding, how committees and journals can protect against biases in knowledge production, and what action should be taken against suspect academic correspondence. Public health researcher Richard Edwards notes, “About a quarter of North American journal editors required disclosure of sources of funding and institutional affiliations. Those arguing against the need for disclosure believe that it is a simplistic and ineffective method of guarding against biased research, and in some circumstances may result in unwarranted prejudice against researches and suppression of scientific dialogue” (Edwards, 1). Others argue that disclosure is “essential to maintain confidence in the research process” (1).

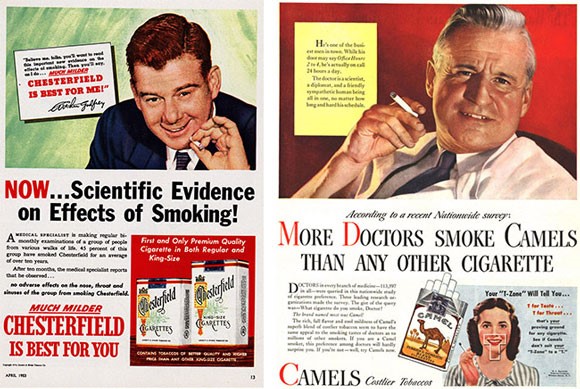

Tobacco Institute ad brandishing scientific evidence and physician approval– Hirsh Health Sciences Library

Politics of Health

Controversy surrounding the TIRC relates to the politics of health as a paradigmatic impingement on scientific knowledge production. Given the nature of the TIRC, Brandt suggests “Fundamental questions about knowing, and about how we know, are illuminated by examining the obstacles that medical science and the public confronted as cigarettes came to be indicted as a powerful cause of serious death and disease” (Cigarette Century, 4). Corporate sponsored knowledge threatened the legitimacy of smoking-cancer research, having a fatal impact on much of the vulnerable public, either too young, uneducated, or otherwise lacking the expertise to discern for themselves the dangers of tobacco (Cigarette Century, 2009). This is an instance of what anthropologist Jill Fisher might call “targeting ready-to-recruit populations” who, while not engaging in clinical trials per se, are similarly targeted by corporate entities who use ignorance as a primary recruiting tool (Fisher, 2007). In fact, a 1987 memorandum of the Institute suggested two prerequisites “to resist smoking restrictions and restore smoker confidence”, namely, reversing the scientific and popular opinion of smoking’s threat to health and restoring its social acceptability (Saloojee et al., 2000). Indeed, a 1969 TIRC document states, “Doubt is our product…Spread doubt over strong scientific evidence and the public won’t know what to believe” (Saloojee et al., 1). In light of these practices (viz. the billions of dollars spent by the TIRC to obscure relevant health facts), historian Robert Proctor coined the term “agnotology”—referring to the deliberate propagation of ignorance—to explore how powerful industries spread deceit to sell product (Proctor as cited by Kenyon, 2016). Thus, he terms ignorance not simply as a passive “lack of knowledge”, but in this case as an active, enforced unknowing. Just so, researcher Richard Edwards writes, “the US Tobacco Institute paid $2500 to $10,000 to authors of letters criticizing the 1993 EPA report that declared environmental tobacco smoke carcinogenic”, aptly calling this a direct violation of scientific purpose (Edwards, 2). Moreover, the struggle of independent studies to firmly establish a causative connection, as opposed to simply correlating smoking and cancer, relates to “political etiology”—a study of the underlying socio-cultural causes of disease (Brawley et al., 2013). Indeed, the rise and fall of the Tobacco Institute, particularly its research division, has sparked much investigation on the medical effects of tobacco use, while leaving much for anthropologists to answer concerning underlying causes of disease, vulnerability of targeted populations, and the validity of health knowledge.

Works Cited

Brandt, Allan M. “Inventing Conflicts of Interest: A History of Tobacco Industry Tactics.” American Journal of Public Health, American Public Health Association, Jan. 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3490543/.

Brandt, Allan M. The Cigarette Century: the Rise, Fall and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. Basic Books, 2009.

Brawley, Otis W., et al. “The First Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health: The 50th Anniversary.” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 18 Nov. 2013, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21210/pdf.

By A Wall Street Journal Staff Reporter. “More Research Needed On Cancer, Smoking Link, Scientist Says.” Wall Street Journal (1923 – Current File), 23 June 1954. ProQuest, search.proquest.com/docview/132105006.

Edwards, Richard. “The Covert Influence of the Tobacco Industry on Research and Publication: a Call to Arms.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health., U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 1999, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10396529.

Fisher, Jill A. “‘Ready-to-Recruit’ or ‘Ready-to-Consent’ Populations?: Informed Consent and the Limits of Subject Autonomy.” Qualitative Inquiry : QI, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 2007, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3044324/.

Kenyon, Georgina. “The Man Who Studies the Spread of Ignorance.” BBC, BBC, 6 Jan. 2016, www.bbc.com/future/story/20160105-the-man-who-studies-the-spread-of-ignorance.

“Master Settlement Agreement.” National Association of Attorneys General. 1998. http://www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa/msa-pdf/1109185724_1032468605_cigmsa.pdf

Saloojee, Yussuf, and Elif Dagli. “Tobacco Industry Tactics for Resisting Public Policy on Health.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, World Health Organization, July 2000, www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?pid=S0042-96862000000700007&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt.

« Back to Glossary Index