Overview

Universal Healthcare is the state in which every resident within a country receives adequate health insurance (Rich and Walter 2017). This includes providing necessary preventative, curative, and rehabilitative services to be comprehensive (WHO 2017). Within the United States, an informal form of universal healthcare existed during the 1800s when systems in more populous cities provided free treatment to patients in poverty in the name of community service (Rich and Walter 2017). After the increase of patients seeking free treatment and the tax increase on provided services, healthcare systems refused to donate their resources and services freely (Rich and Walter 2017).

A more formal version of universal healthcare came into conversation during the early 1900s when poverty became synonymous with unresolved illness due to the luxury health care had proved to be (Rich and Walter 2017). Because the medical industry and the government struggled to come up with a compromising solution that would address the millions of people without access to affordable healthcare, no true action occurred until the passage of Medicare in 1965, granting government-funded care to the elderly population (Rich and Walter 2017). Almost 50 years later, there has been a handful of efforts to implement universal healthcare including the Health Security Act and Affordable Healthcare Act. The Health Security Act, proposed but never implemented by former President Clinton in 1993, would have required most residents in the United States to purchase a comprehensive benefits package from the intermediary health alliances who negotiate with providers for more affordable health plans (Fuchs and Merlis 1993). The Affordable Healthcare Act, proposed and implemented by former President Obama in 2009, enforced that everyone have insurance (public or private) that was made affordable and comprehensive by having the government, employers, and individuals share responsibility in financing it (Mossialos et. al. 2016). Currently, this established healthcare is being repelled and changed due to President Trump’s opposing opinion on the system (Rich and Walter 2017).

In a worldwide context, many European countries established universal healthcare in the early 1900s to stabilize the economy and develop political power (Historical Foundation of Universal Healthcare 2014) (Universal Health Coverage and Health Outcomes 2016). Almost sixty countries have followed suite since due to the beneficial economic progress came as a result (Rich and Walter 2017).

Universal healthcare can be grouped into two main categories: single payer or two-tier (multi-payer). A single payer system is funded primarily through the government, financing all health care except for co-pays and co-insurances (Fuchs 1994). This is the most common form of universal healthcare. Two-tier refers to a minimum insurance provided by the government that can be supplemented by other forms of insurance if desired (Wan and Wang 2017). This could be through a health-savings plan or through private insurance (Wan and Wang 2017).

Figure 1. lists the categorization of many countries that provide universal healthcare (based on this article, insurance mandate states that residents must have some form of healthcare insurance) (Munro 2013).

Perspectives

The arguments for and against universal healthcare are multifaceted. Proponents of this form of health care argue health care itself is a basic right, not an economic good to be sold to the highest bidder (Chua 2006). As a result, providing free healthcare to all in need should not even be an issue. Furthermore, because of the growing correlation between poverty and healthcare, providing insurance to all would help alleviate some of the unnecessary financial burden from paying for expensive healthcare services that keep people in his or her impoverish state (Rich and Walter 2017). Also, it is important to note that uninsured people have a mortality rate of 25% due to the lack of access (Chua 2006). By providing insurance or some form of coverage to all, the number of uninsured people would decrease, which would in turn increase the population of healthy people— the population of a healthy and functioning working force— due to the accessible care offered (Chua 2006).

Antagonists to universal healthcare argue that healthcare decisions should not be put in the hands of the government because the freedom to select his or her own health care would be stripped from the person itself which is politically damaging (Jacob and Sprague 2017). Moreover, the cost of universalizing healthcare would result in a domino effect: the costs of other needed services would be cut, resulting in the loss of jobs and productivity (Jacob and Sprague 2017). Or, taxes would have to increase exponentially to compensate for the cost and the other social systems, both which are economically problematic (Rich and Walter 2017). Making healthcare universal could also cause a demand for the universalization of other resources like food, higher education, etc., completely socializing the society (Rich and Walter 2017). There are even arguments shedding light on how universal healthcare does not improve the quality of healthcare itself— the British National Healthcare System, for example, have extremely delayed response times, making patients wait weeks, even months to receive non-emergent care (Brzezinski 2009).

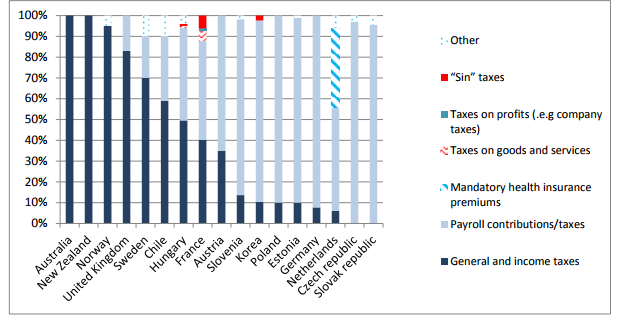

Figure 2. shows how government health expenditures are funded in many countries practicing universal healthcare (Universal Health Coverage and Health Outcomes 2016).

Context

An example of a country with functioning universal healthcare is Canada. The federal government oversees financing most of the services but provinces and territories are the ones that organize and deliver services (Mossialos et. al. 2016). The decentralization of the healthcare system is complemented with nongovernmental organizations that help standardized and improve practices. It is important to note that more than two thirds of the population are privately insured despite the publicly available organizations (Mossialos et. al. 2016).

The United States is an example of a state that is currently working through the process of universalizing health care. As previously mentioned, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), established in 2009, made health care a shared burden among the government, employees, and individuals themselves (Mossialos et.al. 2016). Basic healthcare compensates for emergency services, hospitalization, maternity care, prescriptions, and dental and vision care among other services (Mossialos et.al.2016). Despite these efforts, healthcare has yet to be universal in United States partly due to party politics. The current administration does not wish to continue implementing a universal healthcare system; however, due to some of the successes the ACA has had in reaching people in poverty which has led to some popularity, the administration is hoping to create a better universal healthcare to replace the ACA.

Despite the popularity of universal health care, many countries exist without it, though many of them are underdeveloped. For example, India, China, Mexico, and many African countries have yet to make a transition.

Figure 3. shows a map of the countries (in green) that provide universal health care. United States has yet to be included (Fisher 2012).

Politics of Health

The issues surrounding universal healthcare most closely align with the recognition and derecognition of biological citizenship. Adriana Petryna coined biological citizenship, the abilities that a person gains through biological acceptance from a governing entity, to connect to situations of scarcity and deprivation (2004). Since the system would identify everyone in pursuit to provide accessible healthcare, every population is given a sense of belonging to the government or the organization providing healthcare, which translates to having biological citizenship. When a government fails to recognize all populations, or provide healthcare to all people, there are certain populations that are not being address in membership, limiting their biological citizenship to the government or organization. Universal health care then becomes an issue of how many people can have biological citizenship to the specific entity—all, some, or none.

Universal healthcare can also be associated with Farmer’s principle structural violence, the suffering that arises due to an established limited/restricted access to basic needs (1996). Without healthcare access to every citizen and resident in a country, people living in poverty are predisposed to have little access to healthcare, a basic need, due to high costs of medical services. As a result, poor residents are a victim to healthcare’s structural violence. Universal healthcare attempts to address this suffering by guaranteeing that everyone has access to basic healthcare.

References

Brzezinski, N. 2009. “Does a universal health care system cause a decrease in quality of care?: A comparison of American and British quality in primary care.” Internet Scientific Publications.

Chua, Kao-Ping. 2006. “The Case for Universal Health Care”. AMSA. n.p.

https://www.amsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/CaseForUHC.pdf

Fisher, Max. (2012). “Here’s a Map of the Countries That Provide Universal Health Care (America’s Still Not on It)).” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/06/heres-a-map-of-the-countries-that-provide-universal-health-care-americas-still-not-on-it/259153/

Fuchs, Beth. C. 1994. “Health Care Reform: Single-Payer Approaches.” ProQuest Congressional.

Fuchs, Beth. C. and Mark Merlis. 1993. “Health Care Reform: President Clinton’s Health Security Act.” ProQuest Congressional.

“Historical Foundation of Universal Healthcare”.2014. n.p.

http://www.healthcarereformmagazine.com/economics/historical-foundation-of-universal-healthcare/

Jacobs, W.E., and Nancy Sprague. 2017. “Counterpoint: Universal Health Care is a Socialist Idea.” Points Of View: Universal Health Care 3. Points of View Reference Center, EBSCOhost.

Mossialos et. al. 2016. “International Profiles of Health Systems”. The Commonwealth Fund.

Munro, Dan. 2013. Universal Coverage Is Not “Single Payer” Healthcare. Forbes.

Rich, Alex K., and Andrew Walter. 2017. “Universal Health Care: An Overview.” Points of View: Universal Health Care 1. Points of View Reference Center, EBSCOhost.

“Universal Health Coverage and Health Outcomes.” 2016. OECD.

Wan, G., and Wang, Q. 2017. Two-tier healthcare service systems and cost of waiting for patients. Appl. Stochastic Models Bus. Ind.

WHO. “Universal Health Coverage”. 2017. Worldwide.

http://www.who.int/healthsystems/universal_health_coverage/en/

« Back to Glossary Index