As we discussed in class, when reading Murakami one must pay special attention to even the most trivial details, even if they’re external to the story itself. The styling and thought behind the chapter names, which alternate in the use of italics and in the sophistication of their descriptiveness, foreshadowed the dual plots that characterizes Hard Boiled Wonderland, for example. Immediately following the table of contents, however, are a set of carefully selected images, the frontispiece, that the reader would be at a loss to ignore. The first page is all black, drawing significant attention from the otherwise white pages of the book, and simply depicts two scraps of paper, each with a different cover photo. The simple presentation of the two similar but different items again reinforces the concept of two unique plots. Considering the first plot is about a human data processor trying to save the world from ending, the fact that the first pad of paper conveys a series of music notes (data) spiraling off of a neat scale (doomsday!) seems rather fitting. The second notepad is a little harder to make out at first, but shows a simple river flowing through the woods, as one might expect to find in the much more “organic”plot of the second story, which is set in the outdoors of a rural town with a much heavier emphasis on beasts and nature.

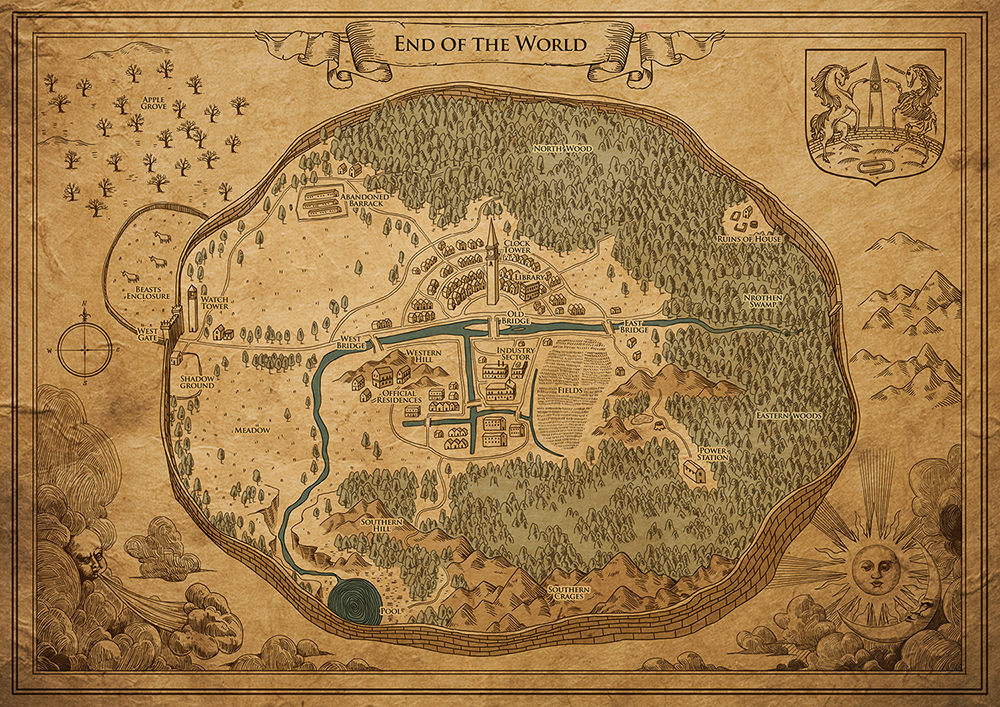

A map of the town is provided on the next page, and immediately open viewing it I was reminded of the story behind Michelangelo’s fresco The Creation of Adam. An Indian physicist named Frank Meshberger noted that the background figures and shapes behind God as depicted in the painting are actually highly reminiscent of an anatomically accurate brain, right down to the brain stem, frontal lobe, and optic chiasm. As Michelangelo had a certified expertise in human anatomy, it is suggested that the artist actually covertly inverted the divine moment of man’s creation that he was commissioned to paint, and instead depicted the moment that man created God (as a reflection of man) from the power of his imagination (big floating brain). The ambiguity in the moment cannot refute the legitimate possibility that maybe Michelangelo thought God is “The Creation of Adam.” Considering this potential artistic move, look again at the map of the End of the World presented in the frontispiece. The city walls are presented in an ovular fashion (that even rolls and seems to lack the rigidity anticipated from brick) that bears an uncanny resemblance to a human brain. The “beasts enclosure” is remarkably spherical, suspiciously outside the walls, and in the exact location that one might expect an eye ball to be observing a profile cut-out of a human head. The centralized town with its different working sectors and is also highly comparable to the organized functionality of the organs in a brain. The path of the roads through the city shamelessly parallel the pathway of the cerebral arterial circle through the brain. To top it off the most central clock tower in the town is recreated outside the brain and flanked by two unicorns contained in a shield, as if a thought bubble were emerging from the brain boasting the ultimate symbols of the imagination: the mythical unicorn. It is no wonder at all that, later in the book, the town of the second plot is eventually revealed to the reader as merely a world generated by the first narrators subconscious, a product of the imagination foreshadowed by art early on. Murakami has successfully employed Michelangelo’s controversial artistic tactics to foreshadow the events of his novel.

.jpg)

Miguel, I really like the way in which you focus on some of the more seemingly minute aspects of Murakmi’s work. In fact I think one of the greatest things about this work is that Murakmi uses all of the tools at his disposal to create—what I believe is (as you and others have mentioned) an allegory of the human brain, consciousness and thought. You do a great job of illuminating how the map of the End Of The World—and thus the entire town itself—is symbolic of the brain and the ways in which it operates. Another key component of this symbolism is the dual plot in alternating chapters that you and others bring up. However, beyond the simple symbolism of the right and left-brain that this dual plot demonstrates, I think this structure literally forces us to engage in a “mind game” similar to that of the narrator in Hard Boiled Wonderland, when he counts the coins in his left and right pockets (Murakmi p. 6).

In a way, reading the two alternating plots, we are forced to keep track of two stories going on at the same time, just as the narrator is tallying and totaling coins in each of his two pockets. Ultimately the narrator combines the two totals, and only then is he confident in the sharpness of his mind. Likewise, these two plots ultimately converge as we realize the “End of the World” is a product of the narrator’s subconscious in Hard Boiled Wonderland. Thus I think Murakmi uses this structure to not only symbolize how the mid works, but to blatantly force us to think in the way our mind already operates. Ultimately, I think Murakmi argues that an ideal society is one that values both “right-brain” and “left-brain” characteristics, in other words, neither a highly data driven society (right brain) or a fantastical society (left brain) are ideal, but rather a society that values concepts from both is ideal, because it fits the way humans think and operate.