“The question is: how to be isolated without having to be insulated?”

Sarah Kareem is Associate Professor of English at UCLA

“The question is: how to be isolated without having to be insulated?” (D. W. Winnicott, “Communicating and Not Communicating Leading to a Study of Certain Opposites,” 1965)

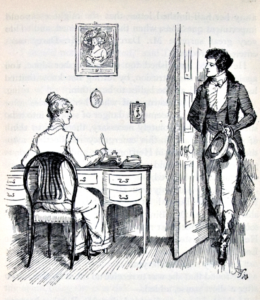

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about a late-nineteenth-century illustration to Jane Austen’s 1813 novel, Pride and Prejudice. The illustration, by Hugh Thompson, appears at the beginning of Chapter 32, and is accompanied by the caption, “Darcy and Elizabeth at Charlotte (nee Lucas) Collins’ house” (1894).

Thompson’s illustration beautifully captures the ambivalence of Austen’s iconic couple. Lizzy, poised to write, meets Darcy’s gaze. He stands in the open door. His feet, dancer-like, suggest movement; but is he stepping in or backing out?

The ambivalence on display in Thompson’s illustration initially drew my interest because I’m writing a book about the practice of putting an object to which you are attached at a remove—the way Darcy, in one scene in Austen’s novel, strenuously attends to his book because he is struggling to resist his attraction to Elizabeth. Conversely, when a book is so absorbing as to be “hard to put down,” laying it aside is a venerable technique for prolonging the narrative. In examples like this, distancing practices both mark and cultivate intimacy.

After the moment Thompson captures, the two go on to discuss—and also display—the subtle modulating effects distance has on intimacy. Darcy and Elizabeth quarrel about whether Charlotte, now married and living fifty miles away from her parents, can be said to have settled near to or far from her family. While Lizzy views Charlotte as living uncomfortably far from her family, Darcy sees the same distance as uncomfortably close. Lizzy, embarrassed and feeling that Darcy is mocking her parochialism, concedes that “[t]he far and the near must be relative, and depend on many varying circumstances.” Meanwhile, their bodies engage in their own advance and retreat. “Mr. Darcy drew his chair a little towards her … Elizabeth looked surprised. The gentleman experienced some change of feeling; he drew back his chair …”

Darcy’s dismay that Elizabeth defends the advantages of settling close to your family stems from his belief that she must surely feel stifled in the confined society of the village of Longbourn. Elizabeth’s retort, “people themselves alter so much, that there is something new to be observed in them forever,” disputes the premise of his belief: that in a small community there is less of human nature to be observed. Elizabeth’s remark implies instead that a perceptive observer understands that there is always more to see even in those whom we know best. Elizabeth’s suggestion that the perceptive observer makes her own amusement, is poignant, as Stanley Cavell observes, because “this implication of a certain genius in Elizabeth at the same time serves more threateningly to seal her isolation (or loneliness), to show her consciousness to risk being unshareable.” Her remark implies, in other words, that the powers of discrimination that make living in this confined world bearable for Elizabeth also sequester her from others. In the end, of course, Elizabeth finds in Darcy someone with whom her consciousness is sharable.

Although I feel grateful that I don’t inhabit a world governed by the marriage plot’s unstoppable momentum, in 2020 it’s also difficult not to wistfully long for some plot—any plot—that might deliver us from our collective confinement. Even as I mourn the straitened circuit we inhabit, I do think we find in Elizabeth’s reply an answer too to D. W. Winnicott’s question, “how to be isolated without having to be insulated?” We may not all have Elizabeth’s genius for observation, but with luck we have enough to find some pleasure in the tiniest of blips in the all-engulfing sameness that is 2020: the slightest dissipation of smoke in the air; the child or pet hovering just outside the Zoom frame; the shade in a two-inch piece of ivory.

Sarah Tindal Kareem is Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Los Angeles. Kareem is currently writing her second book, Vexed, which is about how distance, obstacles, and negative feelings facilitate rather than impede aesthetic attachment. Her first book, Eighteenth-Century Fiction and the Reinvention of Wonder, (2014) recently came out in paperback. You can find her on Twitter @rabidduckwit.

She will be the guest speaker at the 18th/19th Century Colloquium meeting on October 9th from 2-4 p.m. via Zoom. Register here.