“The paradox of education is precisely this – that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated. The purpose of education, finally, is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions, to say to himself this is black or this is white, to decide for himself whether there is a God in heaven or not. To ask questions of the universe, and then learn to live with those questions, is the way he achieves his own identity.”

James Baldwin

Creator Statement

Creator Statement

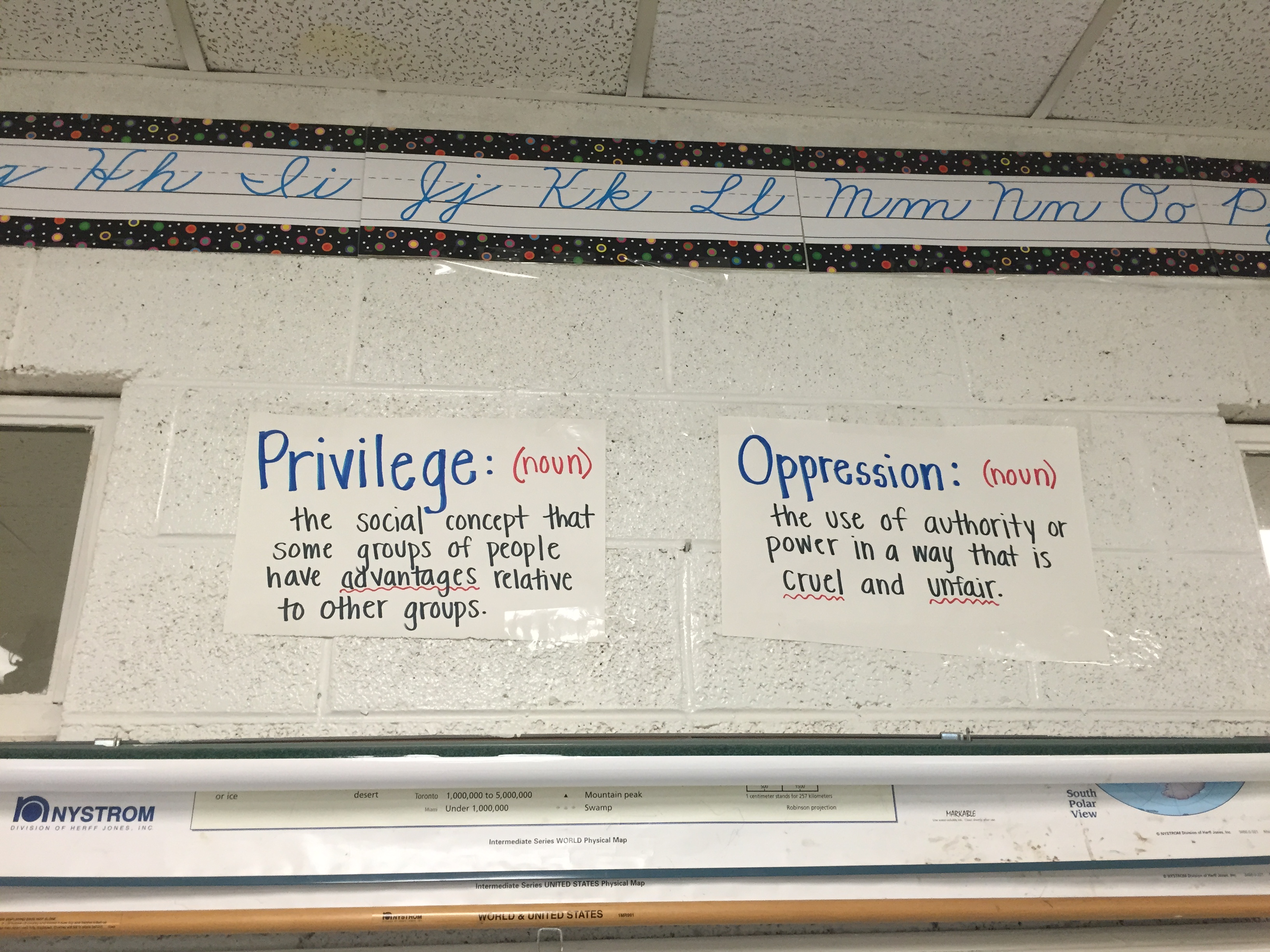

When I began my second year teaching in Lamar, South Carolina, I chose a year-long theme for my fifth grade Social Studies classes: Privilege and Oppression. I taped the definitions on the wall and during each unit, my students would consider how the privilege and oppression of individuals and groups shaped the historic events they studied. My hope, then and now, was that my students would be able to put these complex ideas into both a historical and personal context, and to see how these forces shape their lives today.

Lamar is a small, rural town located near the I-95 corridor, often referred to as the “Corridor of Shame” because of the struggling schools that are located along its path through the state. These schools share similar characteristics: they are overwhelmingly rural, serve a large minority population, and are found in communities with persistent poverty. School districts along the corridor struggle to achieve funding equity with suburban and urban districts, and have trouble attracting high-quality teachers. State and federal education policies and solutions offer ignore the difficult reality faced by rural schools as their students fall further behind in the search for educational access and opportunity.

My experiences in Lamar prompted me to choose rural education as the focus for this practicum, and to shine a light on the unique issues faced by students and educators living and working in rural communities. My practicum explores the struggles of rural schools by examining teacher labor markets, technology infrastructure, school choice reform, and state literacy policies. Through this practicum process, I hope to share the experiences of students and teachers in rural schools, and to use those experiences to shift the education policy conversation to include these often-forgotten voices.

Practicum Linkage

My first practicum deliverable is an infographic video titled “Rural Education Labor Markets.” The video provides basic statistics on the Tennessee teacher labor market in rural schools, with a focus on teacher pay and qualifications. The video also examines the quality of educator preparation programs in rural communities across the state. I conclude with recommendations for the state and for districts hoping to attract high-achieving students into the field of education, and how to incentivize high-quality educators to teach in rural schools.

My second deliverable is an extended blog post examining rural technology infrastructure, titled “Want to Bring Equity to Rural Schools? Start With Ed Tech Infrastructure.” I first wrote this blog post during my summer fellowship with Bellwether Education Partners for their education blog Ahead of the Heard. In it, I reflect on my struggles incorporating technology into my lessons, and propose solutions for rural schools looking to improve their basic internet infrastructure.

My third deliverable is a podcast episode from Pod Save Education, a series created with my classmates that examines education policy and reform in the Trump era. In my episode, I offer insight into current demographic trends in rural schools, with a focus on rural schools in the Deep South. My classmates and I also discuss how President Trump’s main education policy, school vouchers, would affect rural districts.

My fourth and final deliverable is a policy brief on South Carolina’s Read to Succeed legislation, titled “Read to Succeed and Rural Education: How to Improve Childhood Literacy for South Carolina’s Forgotten Students”. The brief offers an overview of the landmark literacy legislation, and offers three core recommendations on how to improve the program for rural teachers and students.

Process Narrative

As I explained above, I chose the topic of rural education because of my time teaching in rural South Carolina, and as a way to explore the experiences of communities that are often left out of our classroom and policy discussions.

This summer, I served as a summer fellow at Bellwether Education Partners in Washington, D.C. Part of my fellowship involved the opportunity to choose a topic of interest and write a blog post for the organization. I knew I wanted to write something about my students in Lamar, and after a little research came up with the topic of educational technology infrastructure. I was lucky that EdWeek also choose ed tech as a summer-long topic, and used their lack of rural school information to prompt my blog response.

During this semester, as I began my practicum project, I was pleasantly surprised to find more information on rural schools than expected, which I owe to the election of President Trump and the increased focus on rural communities. However, few of these resources explored the experiences of people of color in rural communities, despite the fact that nationwide, the rural minority student population continues to grow. Based on these findings, I made the choice to further explore the changing demographics of rural communities for my podcast episode.

While I initially envisioned my practicum as a series of written briefs and reports, presentations from my classmates convinced me to add more multimedia pieces to my final plan. I worked with my podcast group to create a well-crafted introduction for our series to make each episode professional and connected. I also found the infographic video to be a digestible, well-designed way to present a large amount of statistics.

Overall, I think this completed practicum reflects my approach to education policy: it examines core issues of equity and practice through deliverables that are accessible to anyone with a basic interest in the state of education. I am proud of how these pieces explore rural education through various policy lenses, and believe they are a reflection of how I have studied and considered these issues here at Peabody and beyond.

Key Supporting Sources

Below are my key supporting sources for this project. Other general sources are cited on each deliverable page.

1. Marré, Alexander. “Rural Education at a Glance.” United States Department of Agriculture. EIB 171, 2017.

The ERS’ Rural Education report annually examines trends in educational attainment in rural communities and how those attainment levels affect economic prosperity. This year’s report finds that educational attainment varies greatly amongst rural individuals by gender and race, and also finds that on average, rural communities have far fewer degree-holding adults than urban or suburban communities. The report also identifies a relationship between educational attainment and measures of economic prosperity, such as poverty averages and unemployment rates. Overall, the report finds that the diversity of rural communities has increased over the past two decades. It also finds that although educational attainment has increased in rural communities, the rates of growth continue to lag behind individuals living in suburban and urban communities.

2. Johnson, Jerry, et al. “Why Rural Matters 2015-2016: The Condition of Rural Education in the 50 States.” Rural School and Community Trust, 2016.

The researchers behind “Why Rural Matters” deeply explore the state of rural education across the United States by examining a host of statistics covering areas like poverty, race, educational outcomes, student mobility, and demographic changes. Notably, the researchers found that while minority students make up less than 27% of the national rural student population, over 69% percent of minority students are concentrated in 13 states, most of which are found in the South. The authors conclude that rural growth (in total number of students, in the diversity of rural student populations, and in the number of rural students seeking special education services) should propel state and federal lawmakers to consider how best to help rural populations. They also acknowledge the difficulty of creating broad policies to help rural schools, as rural communities across the country differ greatly in their makeup and needs.

3. United States, Congress, “Status of education in rural America.” National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Dept. of Education, 2007.

In 2006, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) developed a new system for identifying, coding, and gathering information on rural communities. This report is the first of its kind to use this new tracking system to report on basic demographics in rural communities across the U.S. After incorporating the new coding, researchers found that while rural schools as a whole had lower rates of poverty than their urban counterparts, poverty in rural America is concentrated in remote areas that primarily serve minority students. Their study of student demographics, achievement, and outcomes signal that recent national policy proposals are unlikely to benefit rural students, as they suffer from unique structural and location-related issues. The study also offers resources tailored to help rural schools bridge the accessibility gap and to consider ways to bring talented educators into rural communities.

4. Campbell, Neil and Catherine Brown. “Vouchers Are Not a Viable Solution for Vast Swaths of America.” Washington D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2017.

During the presidential campaign, Donald Trump’s key education proposal involved creating vouchers for public school students to attend the private school of their choice. Since his election, the Department of Education has explored the feasibility of this plan and begun to take steps toward future implementation. The authors explore the devastating effect this proposal would have on the public K-12 system, and how the proposal leaves behind rural students. Many rural districts have few to no private school offerings for students, and the authors counter that even if new private schools are created in response to the plan, there is no guarantee that they will be higher quality than the local public schools. The authors argue that a broad, “one-fits-all” approach to vouchers ignores the realities of rural schools, and sets those same schools up for failure.