Read To Succeed and Rural Education: How to Improve Childhood Literacy for South Carolina’s Forgotten Students

Taylor Seale, Vanderbilt University—Peabody College

Overview

In response to increasing global economic competition and workforce demands, many states are turning their focus to high-quality education—specifically, improving childhood literacy. There is a growing body of research demonstrating that elementary reading scores can help predict how a child will later succeed in high school, college, or their career (Hernandez 2011). Many states have developed policies to address the country’s literacy gap—in 2014, South Carolina joined their ranks with the passage of Act 294: The Read to Succeed Act.

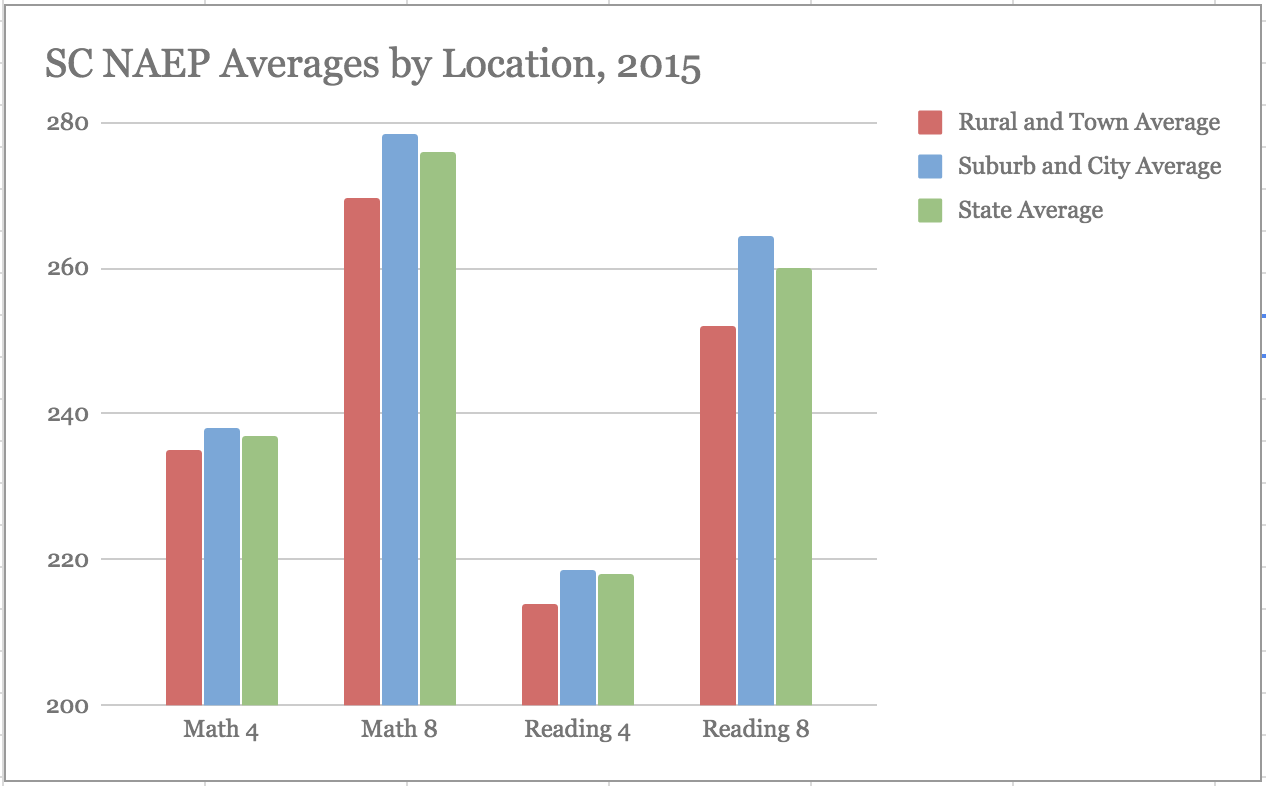

The Read to Succeed Act is a comprehensive package addressing literacy performance at the school, district, and state levels. The state created Read to Succeed in response to studies demonstrating South Carolina continues to rank in the bottom 10th percentile in the nation in literacy achievement (EPE Research Center 2013). When scores are broken down geographically, rural students fare even worse: students in the state’s cities and suburbs outscore children living in rural areas and small towns on all NAEP measures, with the greatest gap in reading (SC NAEP Trend Results 2015).

This brief assesses literacy challenges facing South Carolina students and how the changes implemented through Read to Succeed can successfully improve literacy at all age levels. I also address areas of improvement that the legislature and Department of Education can consider for rural schools as the state moves toward full implementation over the next two years. Suggested improvements for rural districts include:

- Temporarily remove the third-grade retention mandate

- Provide more funding and direction for summer reading camps

- Expand literacy endorsement class opportunities and create guidelines for courses

With these changes and additions, we can ensure an improved academic climate for children across South Carolina, regardless of location, and give children the literacy tools necessary to meet the state’s workforce demands.

South Carolina’s Literacy Deficit

South Carolina’s students are underperforming and unprepared in reading and writing. Before the passage of Read to Succeed, South Carolina ranked 45th in the nation in K-12 achievement. The state lies in the bottom half of states in areas like literacy, student success outcomes, and school funding (EPE Research Center 2013). As evidenced by the chart below, students living in rural areas and small towns score lower than suburban and urban students in all tested NAEP subjects.

Source: South Carolina NAEP Trend Results, SC Department of Education, 2015

A study commissioned by the state in response to these scores and rankings identified four key education challenge areas (Literacy Matters 2010):

- Low student achievement in literacy

- Achievement gaps among minority groups

- Summer reading loss

- Limited number of exemplary literacy classrooms

What Read to Succeed Includes

The state addressed these challenge areas with the input of state education organizations, universities, and district officials. The holistic policy is the most prominent legislation to date focused on improving the state’s literacy climate (Act 284: Read to Succeed). The eight main components of the policy include:

- State, district, and school reading plans

- Mandated third grade retention

- Local summer reading camps

- Provision of reading interventions

- Requirements for in-service educator endorsements

- Early learning and literacy development

- Teacher preparation

- School-based reading coaches

My Recommendations

1. Temporarily Remove the Third Grade Retention Mandate

Read to Succeed requires that if a student does not demonstrate reading mastery by the end of third grade, they must be retained. Students can avoid repeating third grade if they participate in a local summer reading camp and pass a state-administered test at the end of the summer.

While studies of retention efforts in other states demonstrate the policy’s potential for success, implementing a sudden, strict retention mandate can have unintended consequences for teachers and students alike. Retention is also logistically difficult for small, rural elementary schools with few third-grade teachers and literacy support staff.

My recommendation: Require failing students to participate in summer reading camps, but give a five year “grace period” where teachers and principals continue to control retention requirements.

Retention Case Studies: Consequences in Texas and Florida

Florida

Results are mostly positive on the short-term academic effects of Florida’s retention policy, but the long term and behavior effects are mixed (Balkom 2014). One study of non-academic effects found that retained students were more likely to be disciplined or suspended than their socially promoted peers (Ozek 2015).

Texas

Like Florida, Texas’ retainment policy shows some small positive academic benefits, but implementation saw the misuse of the policy by teachers and administrators. For example, many teachers responded to retention enforcement and accountability pressures by increasing their identification of special needs students, therefore reducing the amount of “traditional” students that would fall into the accountability window for testing and possible retention (Booher-Jennings 2005).

My Recommendation, Explained:

- Reading camps will give failing students immediate access to remedial instruction

- Five-year grace period will allow teachers more time to learn about the requirements behind the mandate before implementation, and prepare the leaders of small rural schools and districts for the necessary staff logistics brought on by retention

- Phasing-in will give the state extended time to study the effects of retention

2. Funding and Direction for Summer Reading Camps

Each district must hold summer reading camps for third grade students who did not demonstrate proficiency on the end of the year state assessment. The camps are funded and run by the individual districts, and must be staffed with certified teachers with literacy endorsements (Act 284: Read to Succeed). At the conclusion of the summer reading camp, students will have a second opportunity to demonstrate mastery on a state assessment and advance to the fourth grade.

These camps have the tremendous opportunity to assist failing students and set them onto the path of success. However, the state must be diligent about offering the necessary support to districts if the programs are to be successful, particularly in rural districts where cross-school collaboration is more difficult.

My recommendation: Include additional funding in the yearly Read to Succeed allotment to support reading camps in high-poverty districts, and offer guidelines and lesson plans to summer camp educators.

Importance of Additional Funding for High-Poverty Districts

- The variety of funding levels across counties means that some districts will have less money to put toward running the summer reading camps.

- Additional funding would allow high-poverty districts to give failing students the same level of support they would receive in other areas of the state.

- Additional funding would also allow for the hiring of certified summer staff in rural, high-needs districts.

Importance of State-Created Summer Camp Lesson Plans

- High local control could lead to a variety of implementation across districts.

- State-created guidelines and lessons will give needed direction to district camp leaders, ensuring that every student is receiving consistent and necessary remedial instruction.

- State plans would ensure that regardless of location, students are receiving the same research-backed literacy support.

3. Extend Literacy Endorsement Opportunities and Provide a Course Framework

Read to Succeed requires public school educators at all levels and in all subjects to receive at least one state-approved literacy endorsement. Early childhood and elementary educators require two courses (six credit hours), while middle and secondary educators are mandated to complete one course (three credit hours) (Act 284: Read to Succeed). The endorsement courses are left to the district or schools to administer. Teachers who fail to receive the endorsement through their school or district or who teach in a school or district that does not provide the course must pay out of pocket for the endorsement from a state university.

Requiring a literacy endorsement from every educator is an excellent way to emphasize the importance of reading across all grade levels and subjects. Participation in the courses, however, often requires extra time and money on the part of teachers, and those in rural or small counties often lack the same course offerings as their counterparts in other areas of the state.

My recommendation: Provide alternative endorsement classes that fit educators’ times and budgets, and provide a course framework that standardizes learning across the state.

Alternate Endorsement Opportunities

- SC ETV-broadcast courses

- Saturday courses at local universities

- Weekend development sessions in each of the four state divisions

- Online endorsement course conducted by the state or a participating district

Importance of Literacy Endorsement Course Framework

- As with the district reading camps, high local control could lead to a variety of implementation across districts.

- A state-created framework for the educator endorsement courses would allow educators to receive similar lessons regardless of location or course type (i.e. in person, online, etc.)

Act 284: Read to Succeed. (2014). South Carolina General Assembly. General Session 2013-2014.

Balkcom, Kimberly. (2014). “Bringing Sunshine to Third-Grade Readers: How Florida’s Third-Grade Retention Policy Has Worked and Is a Good Model for Other States Considering Reading Laws.” Journal of Law and Education (43.3). Pages 443-453.

Booher-Jennings, J. (2005). “Below the bubble: “Educational Triage” and the Texas Accountability System.” American Educational Research Journal 42, 2, Pages 231-268.

EPE Research Center. (2013). “State and National Grades Issued for Education Performance, Policy; U.S. Earns a C-plus, Maryland Ranks First for Fifth Straight Year.” Education Week’s Quality Counts Report. Washington, DC.

Hernandez, Donald J. (2011). “Double Jeopardy: How third-grade reading skills and poverty influence high school graduation.” Albany, New York: Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Ozek, Umut. (2015). “Hold Back to Move Forward? Early Grade Retention and Student Misbehavior.” Education Finance and Policy. Volume 10, Pages 350-377.