Meet the Team

Oct. 29, 2018

Callie Weber

Callie is a biomedical engineering major with a neuroscience minor from Hailey, Idaho. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she intends to go to graduate school to earn a PhD in biomedical engineering.

Contact: callie.m.weber@vanderbilt.edu

Lauren Parola

Lauren is a biomedical engineering major with a minor in engineering management from Arlington, Rhode Island. After graduating in May 2019, she plans to pursue a career in biomedical related industries.

Lauren is a biomedical engineering major with a minor in engineering management from Arlington, Rhode Island. After graduating in May 2019, she plans to pursue a career in biomedical related industries.

Contact: lauren.r.parola@vanderbilt.edu

Melia Simpkins

Melia is a biomedical engineering major with a minor in scientific computing from Kailua, Hawai’i. She plans to pursue industry jobs related to biomedical engineering and data analysis.

Melia is a biomedical engineering major with a minor in scientific computing from Kailua, Hawai’i. She plans to pursue industry jobs related to biomedical engineering and data analysis.

Contact: melia.simpkins@vanderbilt.edu

Emma Sterling

Emma is a biomedical engineering major with a minor in Medicine, Health, and Society from St. Louis, Missouri. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she intends to attend medical school.

Contact: emma.k.sterling@vanderbilt.edu

Kelly Swanson

Kelly is a biomedical engineering major with an engineering management minor from Palo Alto, California. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she intends to enter into the biomedical industry field.

Kelly is a biomedical engineering major with an engineering management minor from Palo Alto, California. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she intends to enter into the biomedical industry field.

Contact: kelly.e.swanson@vanderbilt.edu

BME Idea Proposal

Oct. 24, 2018

Executive Summary

In the current research market, there are no devices with the ability to co-culture microbes while keeping each strain distinct and allowing for chemical or nutrient interactions. There is an urgent need for this device to be able to better mimic the in vivo environment in tissues such as the stomach. This device would allow for the analysis of each bacteria individually while also learning how they interact.

We plan to create a co-culturing device that has 3-4 chambers separated by permeable membranes. This will allow the different bacteria strains to interact through the membranes, but not cross the barrier. The membranes will allow for the exchange of chemical signals to mimic how bacteria interact in vivo.

Update: March 26, 2019

Mar. 27, 2019

Since the last project update, progress has been made in the validation of our prototype, creating another iteration of our prototype, and patenting our device.

To begin with, we continued validation of our prototype by ensuring the device was built “true” or so that each flask was the same size and was 1 L in volume. This was tested by placing 2.25 L of water in one flask, and then ensuring that when fully dispersed, 750 mL of water was in each flask. This experiment was also tested with filters in place, which showed the device took 3 min to fully equilibrate with 0.2 micrometer filters. Afterwards, the side ports on all three flasks were blocked off, and 1 mL of water was added to each to ensure all flasks held 1 L of water.

The next validation performed was to test if metabolites were able to cross the filter while bacteria were present in the compartments of the device. To begin with, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was placed in one compartment of the device with the filters in place. Glucose was then added to another compartment of the device, and then the device was placed in an incubator for 24 hours. Samples were then taken from each of the compartments. In theory, if the device is working as designed, these samples should all contain glucose and metabolites produced by the MRSA. This experiment is currently in progress as we await results from the mass spectrometry core.

We have also made progress in creating another, vacuum-safe, iteration of our device to attempt to create a device able to hold bacteria in anaerobic conditions. We have placed the order for this iteration with Hammett Scientific, and are currently awaiting the prototype.

Finally, we are working on the patenting of our device with the CTTC. We had a meeting with Dr. Masood Machingal to discuss our course of action in patenting the device and how to assign authorships. Through this meeting it was determined that ourselves, along with Dr. Townsend would be listed as authors on the patent if we go through with it. Masood did however raise some concerns over the patentability of the device. Though the device is novel and useful, we are unsure how to argue the design is non-obvious. Though we put a large amount of effort to designing the device, putting filters between connected erlenmeyer flasks may not be completely non-obvious. Continuing with this, it has been decided we will come up with a list of claims with the assistance of Dr. Townsend, and then send them to Masood who has agreed to do a preliminary patent search before we file a disclosure to ensure that he feels it is patentable and worth the time to file a patent on.

Update: March 13, 2019

Mar. 13, 2019

Since our previous update, testing has been done on our device to confirm its accuracy to achieving our intended needs. Three different tests were done in order to make sure our device is working properly.

The first test completed on the device was to ensure the device could hold fluid without any leaking and check that the structure is able to facilitate a common media environment. This involved attaching the three flasks as they would be in testing with their rubber gaskets and metal clamps, but without the semipermeable membrane. Water was poured into all three flasks while the spouts were sealed to one another. Copper sulfate was added to one flask and easily diffused to the other compartments without any of the liquid or copper sulfate leaking out. This test proved that the gaskets and clamps formed a tight seal between each flask.

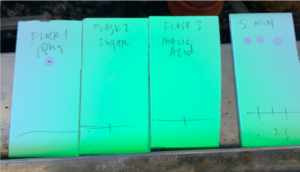

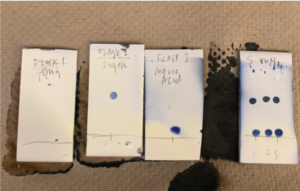

The next test that was completed to ensure the device allows for passage of small particles with membranes inserted into the device, as would occur in a study environment. In this test, three different molecule types were used: triphenylphosphine (Ph3P), a sugar, and L-malic acid. These molecules that are less than the 0.2 micron pore size within the membrane. All three flasks were attached with gaskets and clamps and separated by a semipermeable membrane and solution was added to all three flasks. Ph3P was place in flask 1, the sugar was placed in flask 2, and malic acid was placed in flask 3. After the initial addition of the molecules, the contents of each flask were tested by placing drops from each flask on a piece of paper. The presence of Ph3P could be seen under UV light and the organic molecules like the sugar and L-malic acid stained blue on the paper using alcain blue. From each piece of paper it could be seen that each flask contained only one molecule type. After 5 mins, the flasks were tested again. It could be seen on the paper using UV and alcain blue stain that all three molecules were contained in the flask. This test showed that these small molecules are able to diffuse across the semipermeable membrane over a short period of time. This indicated that the membrane will be effective in allowing communication and exchange of materials between separate bacteria in testing.

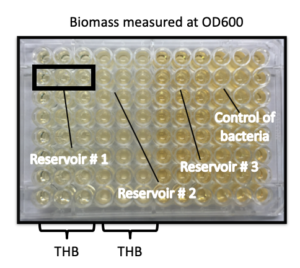

Additionally, a third test was run to ensure that the device is able to maintain cultures that are separate. This was done by setting up the device with clamps, gaskets and semipermeable membranes and placing Todd Hewett Broth in all three compartments. A strain of group b streptococcus was placed in one compartment, while the other two compartments were left empty. The device was left for 24 hours, after which samples from each flask were taken. Optical density testing was completed on samples from each flask as well as on control fluid containing broth and group b streptococcus. OD600 fluid biomass measurements showed that the growth density curve of the control bacteria and the compartment containing bacteria were the same, while the two compartments with no bacteria had a constant optical density. These results indicate that the bacteria were able to be contained within one compartment of the device without crossing over to the other two compartments. This test ensured bacteria could successfully be contained within one compartment of the device.

Finally, a test was run using a cocktail of fecal bacterial in one flask, group B streptococcus in the second, and plain broth in the third. After 10 hours, a sample was taken from the flask originally containing group B streptococcus and subcultured on a blood agar plate. This sample showed growth of pure group B streptococcus bacteria. This test showed the semipermeable membranes were capable of keeping a cocktail of bacteria types physically separated, indicating the device can be used for a multitude of microbes for microbiome experimentation.

Update: February 20, 2019

Feb. 20, 2019

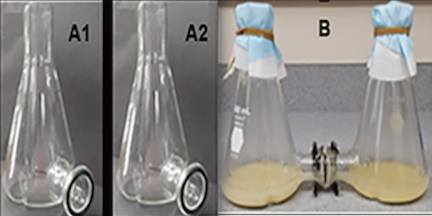

Since last week, we have received our first version of our prototype. The device arrived on 2/18 from Hammett Scientific, and consists of three custom Erlenmeyer Flasks with connective custom glass tubes and specialty clamps to connect all three sections. We have also acquired rubber gaskets which will be used to create an airtight seal between the connective tubes in order to keep our device closed and maintain sterility during use. We have also contacted Dr. Townsend to schedule times to test the device, and are going to coordinate with a lab student later this week with putting Group B Streptococcus strains into the device in order to test with crystal violet stains the functionality of the 0.2 micron filter, which will be acquired later this week.

Along with producing this device, we would like to patent it, and are beginning to work towards this goal as we continue to develop and refine our device. During the last week, we have contacted Karen Rufus at the Vanderbilt CTTC in order to begin putting together a disclosure to patent our microbiome co-culture device. Along with this, we have been working to further our patent search to ensure our device is not too similar to those already patented. This has also led us to begin writing the novel claims of our device. Thus far, the larger novel aspects of our project include:

- Flask structure- two connection tubes near bottom of each flask.

- Three cultures separated in such a way that nutrients and cell signals can passively diffuse from culture to culture without the need for transition through all chambers.

- Can simulate aerobic and anaerobic conditions within the co-culture structure.

These current claims however are very overarching, and will need to be further refined and extended upon for the actual patent, which we hope to work with Karen Rufus on in future meetings.

Looking forward, this week our group will spend most of our time on actually testing the device. The Townsend Lab has offered to allow us to test the device using crystal violet stains in their lab, as well as to utilize their resources to perform colorimetric assays and NMR using synthetic metabolites to confirm the functionality of the 0.2 micron filter between the microbe cultures.

Update: November 15, 2018

Nov. 15, 2018

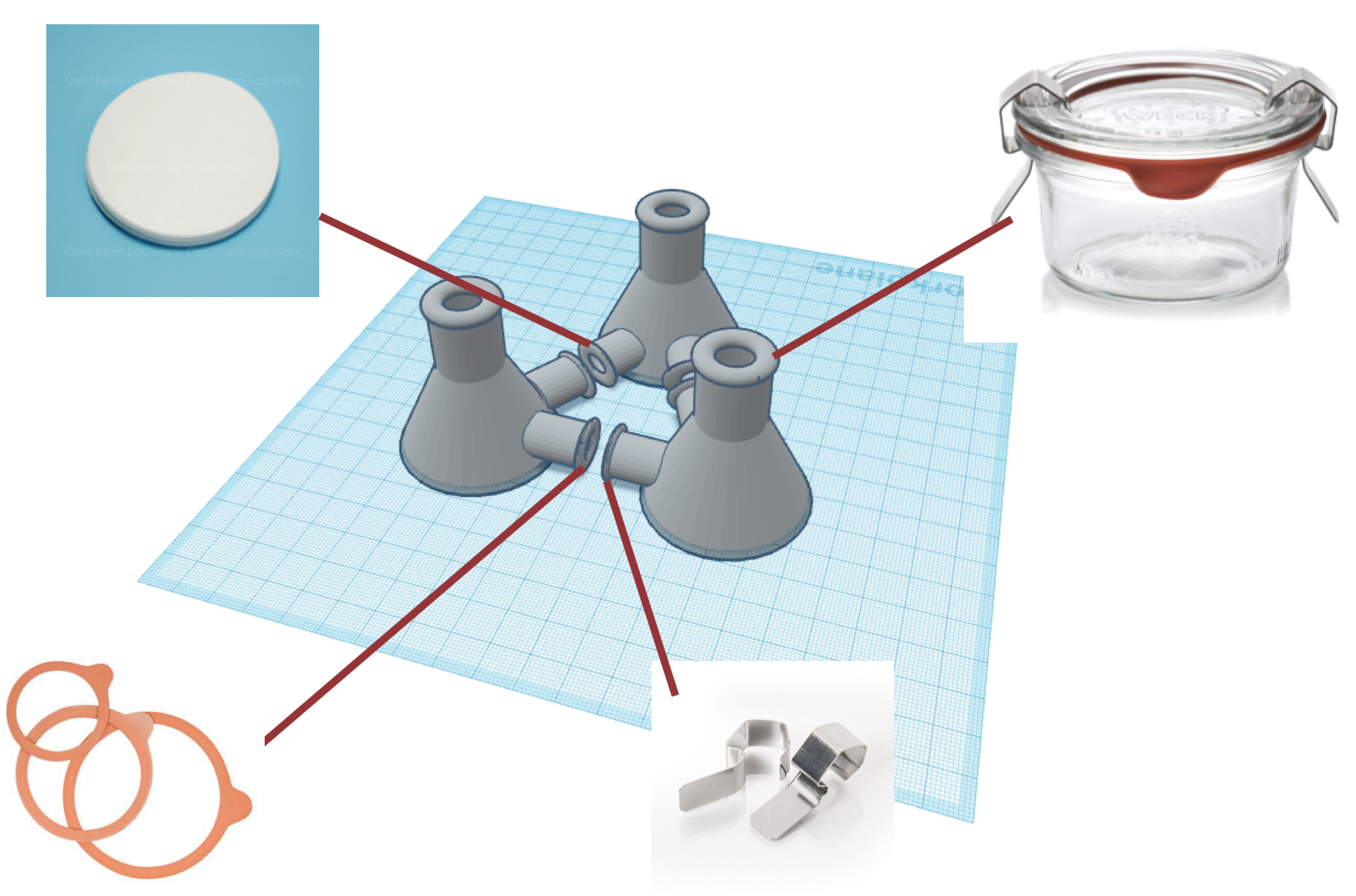

Since the last progress update, we have produced a detailed design for the set of erlenmeyer flasks that will be used in the device along with finding possible sealing materials to create a sanitary and airtight seal. We have also identified the permeable filters that will be used. The next step will be to attain the prototype flasks from the local glassblower we have been put in contact with, and order the sealing and filter components to attempt putting together a working prototype. Material and component choices will be adjusted based on the efficiency and compatibility determined through validation testing by the Townsend Lab. The following is the current material and design choices, along with cost estimates for each:

Flask Prototype Set

$110/flask

$330/set

Airtight Sealing Parts

10 rubber rings for WECK® jars diameter 60 mm

10 rubber rings for WECK® jars diameter 60 mm

$1.00/10 rings

Metal Clamps for Canning Jars, Set of 2

$0.80/2 clamps

Lid for anaerobic conditions

6 glass lids for Weck jars diameter 60 mm –

$1.50/6 lids

Permeable filter

60mm,0.2um,Cellulose Acetate Membrane Filter

$13.60/50 filters

Composite Design

Co-culturing and Synthetic Microbiomes

Nov. 12, 2018

Shi, Y. , Pan, C. , Wang, K. , Chen, X. , Wu, X. , Chen, C. A. and Wu, B. (2017) Synthetic multispecies microbial communities reveals shifts in secondary metabolism and facilitates cryptic natural product discovery. Environ Microbiol, 19: 3606-3618. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13858.

Kim, H. J., Lee, J., Choi, J. H., Bahinski, A., Ingber, D. E. (2016) Co-culture of Living Microbiome with Microengineered Human Intestinal Villi in a Gut-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Device. J. Vis. Exp. (114), e54344, doi:10.3791/54344.

Moutinho TJ Jr, Panagides JC, Biggs MB, Medlock GL, Kolling GL, Papin JA (2017) Novel co-culture plate enables growth dynamic-based assessment of contact-independent microbial interactions. PLoS ONE 12(8): e0182163, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182163

Cira, N. J., Pearce, M. T., & Quake, S. R. (2017). Neutral and niche dynamics in a synthetic microbial community. bioRxiv, 107896.

Project-Specific Importance

Nov. 12, 2018

Donovan S, M, Comstock S, S. (2017), Human Milk Oligosaccharides Influence Neonatal Mucosal and Systemic Immunity. Ann Nutr Metab 2016;69(suppl 2):41-51. doi: 10.1159/000452818

Flint, H. J., Duncan, S. H., Scott, K. P. and Louis, P. (2007), Interactions and competition within the microbial community of the human colon: links between diet and health. Environmental Microbiology, 9: 1101-1111. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01281.x

Townsend, S., and Aldrich, C.(2018), “Nature’s Elixir: Antimicrobial Effects Of Human Milk”. American Chemical Society Webinars

Other Research Applications

Nov. 12, 2018

Wu, H., Tremaroli, V., & Bäckhed, F. (2015). Linking microbiota to human diseases: a systems biology perspective. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 26(12), 758-770.

Wilson B, Rossi M, Kanno T, et al (2018), PWE-126 Low fodmap diet effect on IBS gastrointestinal microbiome and metabolites and prediction of response Gut;67:A181-A182.

Zitvogel, L., Daillere, R., Roberti, M. P., Routy, B., & Kroemer, G. (2017). Anticancer effects of the microbiome and its products. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 15(8), 465.

Update: November 6, 2018

Nov. 6, 2018

Within the past week, our group completed a literature review of relevant papers for co-culture devices for the study of microbiomes. The key papers in the field have been highlighted below.

1. Co-culture of Living Microbiome with Microengineered Human Intestinal Villi in a Gut-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Device[1]

Kim H.J. et al designed a protocol to replicate microbes in the intestinal tract, the colonization of these microbes, and the digestive shear forces that occur during human digestion. This protocol involves culturing epithelial cells on a “basement membrane” to create a monolayer that acts as the intestinal wall on a microdevice, dubbed “Gut-on-a-Chip” by the researchers. After the intestinal wall formed and the permeability was confirmed by TER tests, multiple microbe strains were introduced on the “lumen” side of the epithelial cells to create microbiomes that would exist in the human digestive tract. After a no-flow period of about 1.5 hours, the microbes were able to attach to the intestinal wall. Then, media was flushed at a constant pace to recreate the passing of nutrients and test the ability to remove waste. This allowed the researchers to identify the strains of microbes that could create microcolonies in the niches between intestinal villi and to determine how microbiomes were maintained, despite the constant movement in the digestive system. Researchers developed this dynamic intestinal protocol to improve upon static co-culturing of microbes which usually results in quick overpopulation and short observation periods of 1-2 days. The gut-on-a-chip method allows for both intestinal cells and microbe colonies to remain viable for up to two weeks. However, these devices culture multiple microbes mixed together, including up to 10 microbes in a small area, without the need or desire to separate strains.

Although our device will be made for a static co-culturing set-up, the microbes will be separated and cultured individually. This allows researchers to observe the microbe interactions with each other rather than other components such as the intestinal walls. The gut-on-a-chip design is one example of the need to improve upon current culturing models for microbes and the pursuit of a separated co-culturing device.

2. Synthetic multispecies microbial communities reveals shifts in secondary metabolism and facilitates cryptic natural product discovery[2]

Shi et al. designed a co-culturing device to test its ability to keep bacteria-fungal strains separate, while exchanging metabolites. Since microorganisms play a vital role in drug discovery, it is necessary to replicate the habitat of these microbiomes to properly study how they would react with one another and exchange chemical signals. Prior research indicates how most microbiomes grow physically separated from one another, but still exchange chemical signals. Therefore, it is necessary to create a device that can replicate this homeostatic environment to better understand the importance of this setup within the microbial ecological system.

The device in this study consisted of a 5 L conical flask, a dialysis bag with a two-part semi-permeable membrane, and a mechanical spring attracted to a magnet to maintain the bag’s position. The membrane, spring, and glassware were autoclaved after each use to clean the device, and the device required about 5 minutes to assemble. The membrane had a molecular-weight cut-off of 8-14 kDa, which was an appropriate size to prevent bacteria and fungi from crossing the membrane. The device was tested using Cladosporium sp. WUH1 (host strain) and B. subtilis CMMC(B) 63501 (guest strain). The host strain was allowed to take up the entire environment surrounding the dialysis bag, while the guest strain was restricted to the volume of the dialysis bag. In order to measure the movement of metabolites across the membrane, researchers measured chloramphenicol, a known metabolite, between the strains. Lastly, the researchers replicated an aerobic environment through the use of a swing bed, which was shown by previous studies to allow the growth of aerobic organisms.

Prior studies focused on creating equal-sized growth conditions for each strain, whereas this study created a larger environment (host) and smaller environment (guest) to monitor the interactions. For our study, we must consider whether we would like to make the chambers the same size, or allow for one chamber to be larger than the others. Additionally, our device should model a more accurate aerobic environment. This study used a swinging bag for this process, but we would like to focus on a more direct way to either “turn on” aerobic mode or “turn off.” We should also consider a design that is easily autoclavable and cleaned between each use. Additionally, it should require minimal assembly time.

3. Human Milk Oligosaccharides Influence Neonatal Mucosal and Systemic Immunity[3]

A study completed by Donovan et al. explored the role of human milk oligosaccharides in the development of infant immunity. Infants are at a higher risk for infection due to a less-exposed immune system. Therefore, infants use bioactive components in human breast milk to defend against this risk. Human milk oligosaccharides (HMO) are complex soluble glycans found in free form milk that are believed to assist in immunity. The amount of HMO in milk varies based on the type and maternal genetics.

This study outlined the roles of glycans in the body. The oligosaccharide composition of breast milk impacts the development of bacterial colonies within the infant, causing changes in their microbiota metabolic activity. An infant’s microbiome development begins in utero and continues to develop throughout the first few years of life. Studies show that breast fed or infants consuming supplemented formula were better at utilizing HMOs as carbon sources. HMOs must be broken down properly because oligosaccharides influence the infant mucosal and systemic immune system. HMOs are also believe to have a role in immune-related gene expression and protein production. Depending on the bacteria and HMO combination, the impact on gene expression varies. Additionally, HMOs are believed to affect the circulation of immune cells.

Recent studies found that infants fed HMO-supplemented formulas had lower incidence of diseases including bronchitis and lower respiratory tract infections. This indicated that HMOs could have a role in the innate and adaptive immune system through interactions with gastrointestinal cells. For this reason, adding HMOs to infant formula could be beneficial in enhancing immunity and overall digestive health. Our microbiome device aims to simulate the environments tested in this paper to gain a greater understanding of the components of human milk, and could eventually be used to enhance baby formula to promote infant health.

4. Novel co-culture plate enables growth dynamic-based assessment of contact-independent microbial interactions[4]

Moutinho et al. proposed a co-culture device similar to the one we had proposed, except only allowing for the co-culture of two microbes at the same time. Their goal was to design a low-cost, vertical membrane, co-culture device in which microbes could be kept separate, while still allowing for the study of chemical signals between colonies. The group produced mock-ups in SolidWorks 2015, which they then created using a mixture of water-jet cutting, milling, and laser cutting. The design included two chambers capable of holding 4 mL of liquid per chamber made out of polypropylene. The chambers were attached by machine bolting with an aluminum base. Between the two chambers, an Isopore™ Membrane Filter was used as a semipermeable membrane to separate the cultures, and silicon gaskets were used to adhere the chambers together to prevent contamination around the membrane. These devices allowed for optical density data collection, an analysis technique that could not be used in previous co-culture device platforms. Similar to the co-culture device presented in this paper, we hope for our cultures to allow for optical density data collection among separate microbe cultures, while still allowing for metabolites and nutrients to be shared across cultures. However, our device will improve on this design as we will allow for the study of 3-4 microbe species in one device.

5. Ultrathin transparent membranes for cellular barrier and co-culture models[5]

One of the most important components of the co-culturing device is the membrane. In a study done by Carter et al., a unique membrane was created and tested in comparison to existing forms of membranes. The study looked at how to improve current membranes that are frequently used in in vitro testing. Current membranes are incompatible with imaging analysis techniques. More importantly, they found that the polymeric track-etched membranes, which are currently in use, are not physiologically representative. Although the membranes are permeable to small molecules, they are substantially inferior to in vivo reality in representing the physical interactions that exist between co-cultured cells.

This study designed a new silicon dioxide membrane, which is a transparent ultrathin membrane. This membrane has: 1) porosity exceeding 20% and 2) a thickness comparable to that of the vascular basement membrane allowing it to support physiologically relevant cellular interactions. In testing the membrane capabilities, the researchers focused on the following: 1) membrane fabrication and physical properties 2) cell spreading 3) cell proliferation 4) cellular imaging and substrate autofluorescence and 5) cellular co-culture. Lastly, Carter et al. found that through the use of fluorescent dyes, cells were either able to form gap junctions across the silicon dioxide membrane or secrete extracellular vesicles across the membrane. This verifies that the cells were able to get within physiological distances to send signals to one another.

However, there were also limitations to this paper. The paper stated that they were able to facilitate physical contact through the membrane. However, physical contact is undesirable for our device, so further research into the type of physical contact is important if we decide to utilize a membrane such as this one. The membranes created by this research team have been cited as having a straightforward fabrication process, as well as the successful ability to facilitate new and improved barrier and co-culture models. Since this closely follows the goal of our device, we will use this as well as other studies about fabricated membranes to assist in creating the separations between our compartments.

Our next goal for our project will be to produce a detailed CAD design of our intended device to be produced and send it to the glass blowers we have been put in contact with. We hope to receive feedback from the glass blowers on feasibility of design and if they are capable of fulfilling all of the design parameters that we are intending to meet.

[1] H. J. Kim, J. Lee, J.-H. Choi, A. Bahinski, and D. E. Ingber, “Co-culture of Living Microbiome with Microengineered Human Intestinal Villi in a Gut-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Device,” J. Vis. Exp., no. 114, pp. 3–9, 2016.

[2] Y. Shi et al., “Synthetic multispecies microbial communities reveals shifts in secondary metabolism and facilitates cryptic natural product discovery,” Environ. Microbiol., vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 3606–3618, 2017.

[3] S. M. Donovan and S. S. Comstock, “Human milk oligosaccharides influence neonatal mucosal and systemic immunity,” Ann. Nutr. Metab., vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 42–51, 2017.

[4] T. J. Moutinho, J. C. Panagides, M. B. Biggs, G. L. Medlock, G. L. Kolling, and J. A. Papin, “Novel co-culture plate enables growth dynamic-based assessment of contact-independent microbial interactions,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 1–12, 2017.

[5] R. N. Carter, S. M. Casillo, A. R. Mazzocchi, J. P. S. Desormeaux, J. A. Roussie, and T. R. Gaborski, “Ultrathin transparent membranes for cellular barrier and co-culture models,” Biofabrication, vol. 9, no. 1, 2017.

Update: November 1, 2018

Nov. 1, 2018

Recent progress in producing a co-culture device for microbiomes has led to preliminary computer-aided drawings (CADs) of our device design ideas. At this point in our project, we have not made a decision on whether we would like to make our device in glass petri dishes or in connected erlenmeyer flasks. Both options come with a variety of pros and cons that we have mapped out in the past couple of weeks. The glass petri dish design would come at a lower cost, and would only require the production of holders in the dish to maintain the placement of the semi-permeable membrane between sections of the device. This dish design is however much more susceptible to contamination as the lid is less securely placed on the device. One modification we brainstormed to prevent this would be a thin ring of pliable plastic on the interior lip of the lid to produce a tighter seal on the device. This does however limit oxygen and carbon dioxide movement into and out of the device which could have potential negative effects on the cells. This plastic would also have to be fairly heat resistant in order to be autoclavable for sterility. The interconnected erlenmeyer flasks would provide a larger cell culture surface area for our microbes. This design also has a much smaller chance of accidental mixing of microbes between the co-cultures as they would be separated by a much greater distance (our chosen length of tubing). The erlenmeyer flask design would however come at a much greater cost as we would have to have our flasks adjusted by a professional glass-blower to design air-tight tubing ports in the flasks. Another complication would be the insertion of semi-permeable membranes into tubing to connect the flasks.

In researching the beginning steps of our project, we have attained the name of a glass blower in the Nashville area, and have been given general price ranges for our device prototype production. Eddie Bishop from the University of Tennessee and his wife have both been in contact with our advisor, Dr. Steven Townsend, as they both work in the glass blowing. They have priced the production of an airtight working prototype to be about $500. Using this information, we are currently discussing steps to cut down on these costs in order to lessen the cost for redesigning and reiterating prototypes. We have also located porous membrane options online which could be redesigned to fit our need. We intend to use a 0.22 micron filter similar to those found in Millipore Millex Syringe Filters. These filters are selectively permeable to objects smaller than 0.22 microns, which would be small enough to prevent the passage of microbes through the filter, but still large enough to allow the passage of chemical signals and nutrients.

Finally we have discussed with the Townsend Lab the testing of our device. Once prototyped, the device will be handed off to graduate level students in the lab to test the separation of microbes, sterility, and chemical signaling. We have determined that the graduate students will begin testing first for separation and sterility. To do this, the graduate students will start three separate bacteria cultures in the three different segments of our co-culture device. The bacteria cultures will be: Cocci (spherical) bacteria, Bacilli (rod-shaped) bacteria, and Spirilla (spiral) bacteria. Utilizing light microscopy, it will be possible to determine if any bacteria have crossed the membrane by observing the shapes of the bacteria in each compartment after extended incubation periods. This will allows the grad students to determine over time if our device successfully keeps the cultures separate. Determining sterility will also be clear in these culture examinations as contamination will appear in a different form than those bacteria purposefully being cultured.

Prototype Designs

Oct. 29, 2018

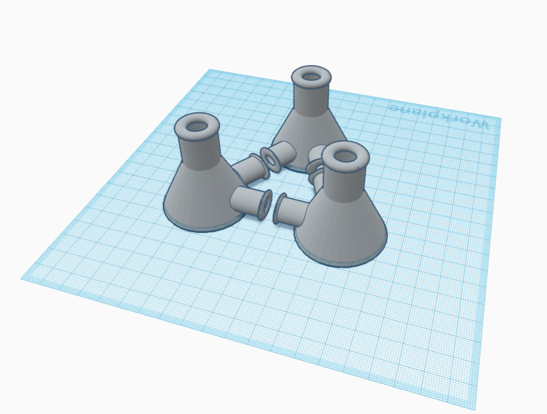

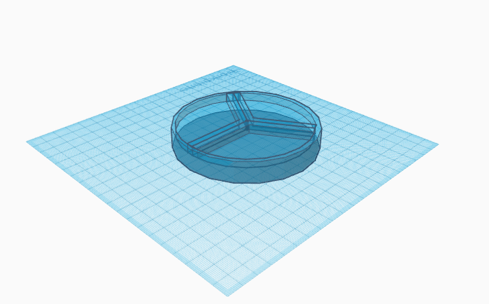

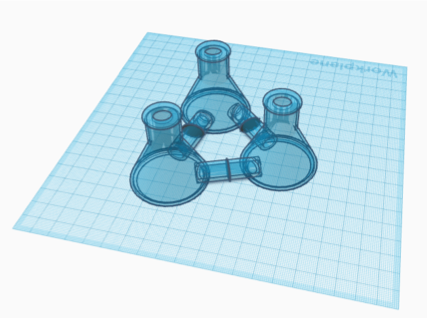

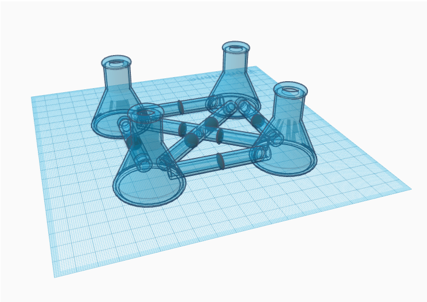

Prototype of Final Design

The final design may be similar to the following 3-D figures. These visual representations of possible prototypes were made using TinkerCad.com. The team will converge on a final solution based on validation tests and cost of production.

The 3-compartment petri dish solution (Figure 1) would be similar to existing culturing dishes, with permeable walls used to create three slices on the culturing surface. The three sections would be used for separate microbes and the walls would allow nutrients to transfer among the microbiome without allowing for physical mixing of the microbes themselves.

The Erlenmeyer flask designs (Figure 2, Figure 3) would use separate flasks for each microbe. The connecting tubes between the compartments include a permeable membrane that blocks the passage of microbes into other chambers. With shared media in all of the throughout the device, chemical signals and nutrients can be shared between the microbes, mimicking a microbiome of either 3 (Figure 2) or 4 (Figure 3) different microbe species.

A rough prototype existed in the Townsend Lab, before it broke earlier this week and consisted of two Erlenmeyer flasks with spouts at the base to be connected to each other with the permeable filter in the middle (Figure 4). The team is using the base design to expand the co-culturing to at least 3 compartments, and aims to provide a cap that allows for anaerobic conditions.