“The facts speak for themselves,” is a favorite maxim. Sometimes they do. But when they don’t? This liminal state between unequivocal truth and falsehood is where politics finds itself a comfortable home.

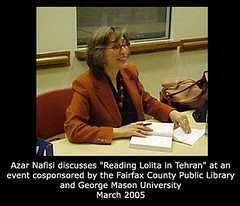

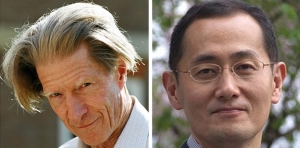

The time following the announcement of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine presents a special opportunity for the public communication of science. For a fleeting moment, you have the undivided attention of a newly captive audience. The tragedy is that politics ultimately inserts itself into the discourse and poisons the well, making it impossible for effective communication to materialize.

The most egregious example of this phenomenon comes from a piece written by Will Saletan at Slate, who opens with the following remarks:

Shinya Yamanaka, a scientist at Kyoto University, loved stem-cell research. But he didn’t want to destroy embryos. So he figured out a way around the problem.

His intention is to make a case for the moral prerogative that supposedly guided Yamanaka’s work, but his “facts” simply do not obtain. In the end, his article constitutes one of the worst-offending mischaracterizations of Yamanaka’s work seen to date.

Deconstructing a False Narrative

Saletan’s argument is built upon the following central premises: (1) Yamanaka desires an alternative to hESC; (2) This desire is motivated by moral objection to the use of embryos; (3) Yamanaka’s work avoids or eliminates the need for embryos; and (4) Yamanaka’s research is an alternative to hESC.

Taken together, these premises lead Saletan to derive the conclusion that Yamanaka’s Nobel Prize-winning research was a moral crusade against the use of embryos in stem cell research.

In making the case for this argument, Saletan generally assumes that premises (1), (3), and (4) are valid and therefore rallies around providing support for premise (2). Thus, the burden of proof is to provide compelling textual evidence for Yamanaka’s alleged moral objection as an underlying motivator in his work.

It is along both these lines that Saletan ultimately fails. I will address the problem with these tacit assumptions (1, 3, and 4) in greater detail in a separate post, but for now I want to focus on the more immediate issue at hand: the misappropriation of science as a means to a political end, particularly through the mischaracterization of research and manipulation of published literature.

Lines of evidence

Saletan utilizes four major lines of textual evidence: (1) The introduction of Yamanaka’s Cell paper; (2) A widely cited New York Times article; (3) A New Scientist interview; and (4) External commentary and responses, including that of anti-abortion groups and the science press.

Commentary from other groups allegedly asserting an ethical relationship or claim of a “moral achievement” is not proof of Yamanaka’s moral objection, so we can eliminate this from our discussion.

This narrows Saletan’s support to (1-3). I will examine each in detail, using an exegetical approach to the text. If Saletan’s claims from these three lines of evidence fail to obtain, then he fails to prove the second premise, and his conclusion is false.

The science literature

Saletan begins by arguing that Yamanaka’s research article itself is evidence that a moral objection to the use of embryos is the motivating factor behind his work. He reasons,

In the introduction to their Cell paper, Yamanaka and his colleagues outlined their reasons for seeking an alternative to conventional embryonic stem-cell research. “Ethical controversies” came first in their analysis. Technical reasons—the difficulty of making patient-specific embryonic stem cells—came second.

It appears that this would be a clear cut case of “true” or “false”—either the text states this or it does not—but Saletan’s claims are, in fact, fairly convoluted. First of all, Saletan has misinterpreted the meaning of the text, and secondly, he absurdly suggests that “order of mention” is somehow symbolic proof of significance, based on his faulty analysis.

Yamanaka and colleagues (Takahashi et al., 2007) begin their paper by identifying the two major properties of embryonic stem cells that make them so valuable for research: (1) indefinite self-renewal and (2) pluripotency. It is these properties, the authors continue, that create the vast potential for therapeutic applications. In the very next breath, the authors implicitly note that the scientific application of the cells into therapeutic ends has been halted by ethical controversies generated by the political climate. This interpretation is made possible by the wording offered in the text itself: the “controversy” is what “hinders” the research, Yamanaka carefully suggests.

The introduction to this award-winning paper is only five sentences, but it communicates much more than meets the eye for anyone familiar with the field of stem cell biology. Let me point out the glaring elephant in the room that Saletan is choosing to ignore: politics impedes science. And guess what? Strict limitations placed on hESC in Japan have made this type of research practically impossible. Yamanaka and his colleagues did not seek out an alternative to research on embryos; they never had a choice to begin with.

Saletan misses the point that the authors mention “ethical controversies” because, in fact, it is the number one reason why the therapies have yet to be achieved. This is relevant to his logic of “order of mention,” since it flips it on its head. The problem of immune rejection prevails precisely because of limited funding and extreme bureaucratic red tape—problems caused by political controversy. If you cannot freely research hESC, then you are not well-equipped to address the problem of patient specificity with these cells. In the face of such powerful structural limitations, which is more feasible: overhauling the political system, or modifying one’s own research agenda? iPS has gained legitimacy as a result of this. And of course, iPS was not invented out of thin air to address these problems. Yamanaka’s history of research happened to intersect with these sociopolitical problems that currently burden research.

Allusions to ethical problems in the literature offer no real evidence that moral objection to the use of embryos was an underlying motivator for Yamanaka in the execution of his research. But the literature offers overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Like any high-quality journal article (this was published in the prestigious Cell, after all), Yamanaka’s work is organized and concise. At multiple points in his paper, he directly states the purpose, outcome, and implications of his research. For example, the abstract begins with the following statement-of-purpose: “Successful reprogramming of differentiated human somatic cells into a pluripotent state would allow creation of patient- and disease-specific stem cells” (Takahashi et al. 2007, 1). His team concludes the following outcome, which reinforces the stated purpose: “Our study has opened an avenue to generate patient and disease-specific pluripotent stem cells” (Takahashi et al. 2007, 9). Finally, they lead into what is arguably the most exciting part of their research: the implications. They are one step closer to achieving therapeutic outcomes.

But in case that were not enough, an article penned solely by Yamanaka offers yet more insight. The crux of his paper centers around one main idea: “Generating pluripotent stem cells directly from cells obtained from patients is one of the ultimate goals in regenerative medicine” (Yamanaka 2007). Browse any of the literature and you will see that this is the prevailing theme. Yamanaka and his colleagues want to save patients’ lives. And so, the pursuit of patient and disease-specific stem cells is the reason for their research. With hESC research so limited, iPS technology drives their efforts.

“But the New York Times article says…”

Groups eager to politicize his work will be unsatisfied by this analysis. But what about the embryos, they protest, clinging to the notion that Yamanaka is their moral crusader. For them, the strongest evidence seems to come from a New York Times article published at the end of 2007. Anti-abortion groups have jumped all over it, latching onto a single quote in their desperate attempt to assert, “he’s one of us.” Saletan himself falls victim to this crime of [uncritical thinking], as he turns to this single excerpt as proof of his position:

Inspiration can appear in unexpected places. Dr. Shinya Yamanaka found it while looking through a microscope at a friend’s fertility clinic. … [H]e looked down the microscope at one of the human embryos stored at the clinic. The glimpse changed his scientific career. “When I saw the embryo, I suddenly realized there was such a small difference between it and my daughters,” said Dr. Yamanaka. … “I thought, we can’t keep destroying embryos for our research. There must be another way.”

Let us not forget that the author is telling a story. When is it ever reasonable to accept a story at face value without subjecting it to logical scrutiny? Secondary sourcing is fallible; narration is highly unreliable. Thus, we must approach any story by exercising our critical thinking skills as appropriate to separate fact from fiction. There are several reasons why you should approach this particular narrative—the framing of the story, not Yamanaka’s quote itself—with a similar degree of reservation and skepticism.

Intuitively, we know that Yamanaka does not actually believe that embryos under a microscope are morally equivalent to his daughters. If he held this belief, he certainly would not be involved in the field of stem cell biology, which requires pervasive manipulation and destruction of hESC along all lines of research. His preference to not use hESC does not presuppose that he is morally against the use of embryos; this is a false dichotomy. There are many other plausible explanations. On a practical level, it may indicate a desire to avoid obstacles to research; on a personal level, it may suggest a particular philosophy toward human nature that has not yet been accounted for.

But we are not limited to educated guesses. There is plenty of other evidence from which to draw our conclusions. In a December 2007 interview with New Scientist, Yamanaka is asked how he felt when he discovered that his experiment was a success: first surprise, then pride, he responded. And then he tells us this:

At the same time I felt kind of responsible for this technology we had developed because now everybody has the means to develop embryonic-like cells. And they can do it without any approval from the authorities.

On one hand, this is a crucial acknowledgement that regulatory oversight plays a major role in the field, which supports my analysis of the introduction to his Cell paper. iPS cells expand the world of practical research opportunities; hESC constrain it—at least right now. But most importantly, he indicates ambivalence regarding the ethical implications of the technology that he just brought into existence. Notably absent from his remarks is any suggestion of having “saved” the embryos, or a vindication of his so-called “moral project.”

Rather, his comments display a sense of ethical concern far more sophisticated than the current debate raging over disposal of excess embryos created through IVF. In this way, Saletan misses the mark completely. Yamanaka implies that his work is not equivocally “good,” at least in the sense of the black and white morality proposed by Saletan’s line of thinking (i.e., “iPS good, hESC bad”). Consider the implications. In theory, iPS technology would make it possible for me, as a female, to create sperm cells from my own DNA and combine them with my own eggs to create a new conceptus. All in a petri dish. This would not be a clone—it would be a genetically distinct organism. There is nothing in our modern human existential experience that could account for a creation like this. A new type of genetic human would be brought into existence. What would this mean for our humanity?

Yamanaka is deeply humble, but what I have gathered from reading both his work and personal interviews is that this is a man with a profound capacity for complex ethical reasoning. He is cautious about his work and forward-thinking about the field. He is, in every sense of the term, a humanist. Certainly, he brings this type of moral awareness to work with him every day. And I am grateful for scientists like him, who embody an ethic of virtue in their commitment to improving the existence of mankind.

At the end of the interview, Yamanaka offers some final thoughts:

We also need a more detailed comparison between iPS cells and embryonic stem cells in terms of what they do. If it is proved that iPS cells are as good as or better than embryonic stem cells, I think they can replace them. I do want to avoid the use of embryos if possible. Ultimately I think that patients’ lives are more important than embryos, but I do appreciate that embryos can become beautiful babies as well.

He regards embryos with a degree of prudence out of respect for human nature, not a desire to abide by a moral absolutist, categorical imperative. His position reflects a carefully reasoned stance closer to the middle, but certainly on a liberal end. It is permissive, rather than restrictive. A central tenet to his philosophy is the respect for potentiality. This is not the same as belief in embryo personhood, or of a supposed moral equivalence to full-fledged human beings, as Saletan and the NYT article would mislead us into thinking.

Incredibly, Saletan ignores the surrounding context and meaning inherent to this passage and misconstrues a choice quote in a subtle but powerful way. He writes this:

Yamanaka explained his ambivalence to New Scientist in December 2007. “Patients’ lives are more important than embryos,” he said. But “I do want to avoid the use of embryos if possible.”

Compare the two passages and note the differences. Yamanaka’s statements mean something qualitatively different when the order is manipulated and context is removed. Saletan erroneously suggests that Yamanaka feels ambivalence about the use of embryos; he manipulates Yamanaka’s words to construct this false pretense of ambivalence. But Yamanaka’s original words and statements provide no such interpretation. Rather, Yamanaka’s own moral position is clear, well-reasoned, and non-contradictory. Thus, Saletan has conjured a moral dilemma where none exists.

It it through this move that Saletan reveals himself as pandering to religious ideology: we have a categorical imperative to avoid the use of embryos in research at all costs, he implies. This is the ultimate duty, a goal towards which we must strive. This reeks of moral absolutism. Yamanaka’s views are not in conflict, but in fact exist harmoniously alongside one another.

Yamanaka does not believe that it is immoral to use embryos in research. He places a premium on existing human life over the potentiality of embryos, and he supports the continuation of embryonic research as long as it offers promise for therapeutic and regenerative medicine. But his humanistic philosophy towards life and science supports the idea that, if it is not necessary to destroy embryos in research, then by all means we should avoid doing so. This is a liberal view to research held by many in the science community.

This is not a man who, through some divinely-inspired teleological effort, devoted his life project to finding an alternative to the use of hESC research. Yamanaka is not your personal moral crusader; he is, first and foremost, a scientist. The work of a scientist is qualitatively different from that of an activist. His life of experimental research may, in the distant future, prove to complement his humanist views, but let’s not project our political agenda onto his work.

For this, the guilty parties should win an award for unethical misappropriation of science.

___

Sources:

Kazutoshi Takahashi, Koji Tanabe, Mari Ohnuki, Megumi Narita, Tomoko Ichisaka, Kiichiro Tomoda, and Shinya Yamanaka. 2007. “Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors.” Cell 131:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019.

Shinya Yamanaka. 2007. “Strategies and New Developments in the Generation of Patient-Specific Pluripotent Stem Cells.” Cell Stem Cell 1:39-49. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.012

Will Saletan. 2012. “The Healer: How Shinya Yamanaka transformed the stem-cell war and made everyone a winner.” Slate, October 9. Link