Research

General Interests

My research interest is to understand how large mammals choose the habitats they use and how human activities (e.g. land-use and land-cover changes) affect their long-term persistence. Large mammals are fundamental for community and ecosystem structure as they usually represent the largest biomass of an area, they occupy distinct trophic levels (top predators, meso-predators, herbivores) and they are frequently the first ones to disappear from areas where there is human interference, because of direct (poaching) and indirect effects (habitat reduction, increased isolation, domestic diseases).

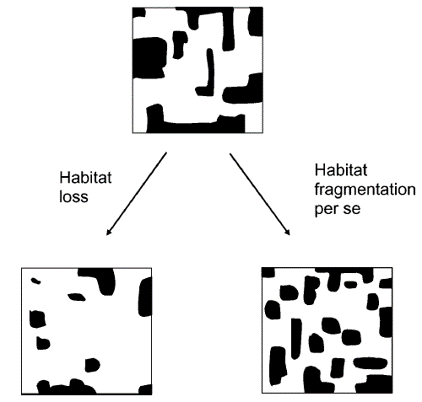

(Source: Fahrig 2003)

I have been conducting my research in Brazilian ecosystems because Brazil harbors one of the world’s greatest diversity of species and ecosystems, and a gradient of history of human exploitation, with some ecosystems with more than 100 years of land change, others with less than 50 years of land change, and few with large tracts of continuous pristine habitats. Also, as Brazil’s economic growth is intensified, so are the challenges of maintaining economic growth and preserving natural systems and biodiversity. Understanding the effects of land use and land-cover change on Brazilian ecosystems will help in efforts to reduce biodiversity loss and harmful effects on ecosystem function at local and regional scales, as well as on the global scale.

Current Research

My current research involves understanding large mammals’ spatial needs at multiple spatial scales (e.g. regional and local).

(Jorge et al. 2013)

(Lima et al. 2014, 2012)

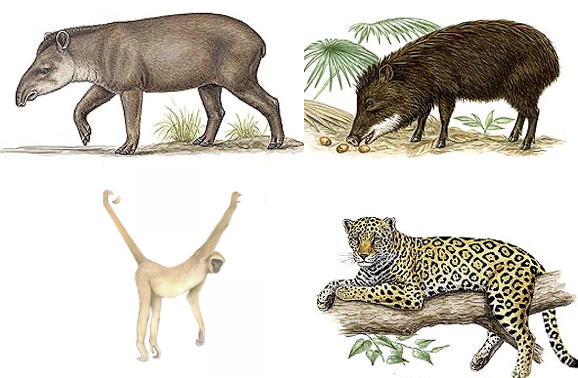

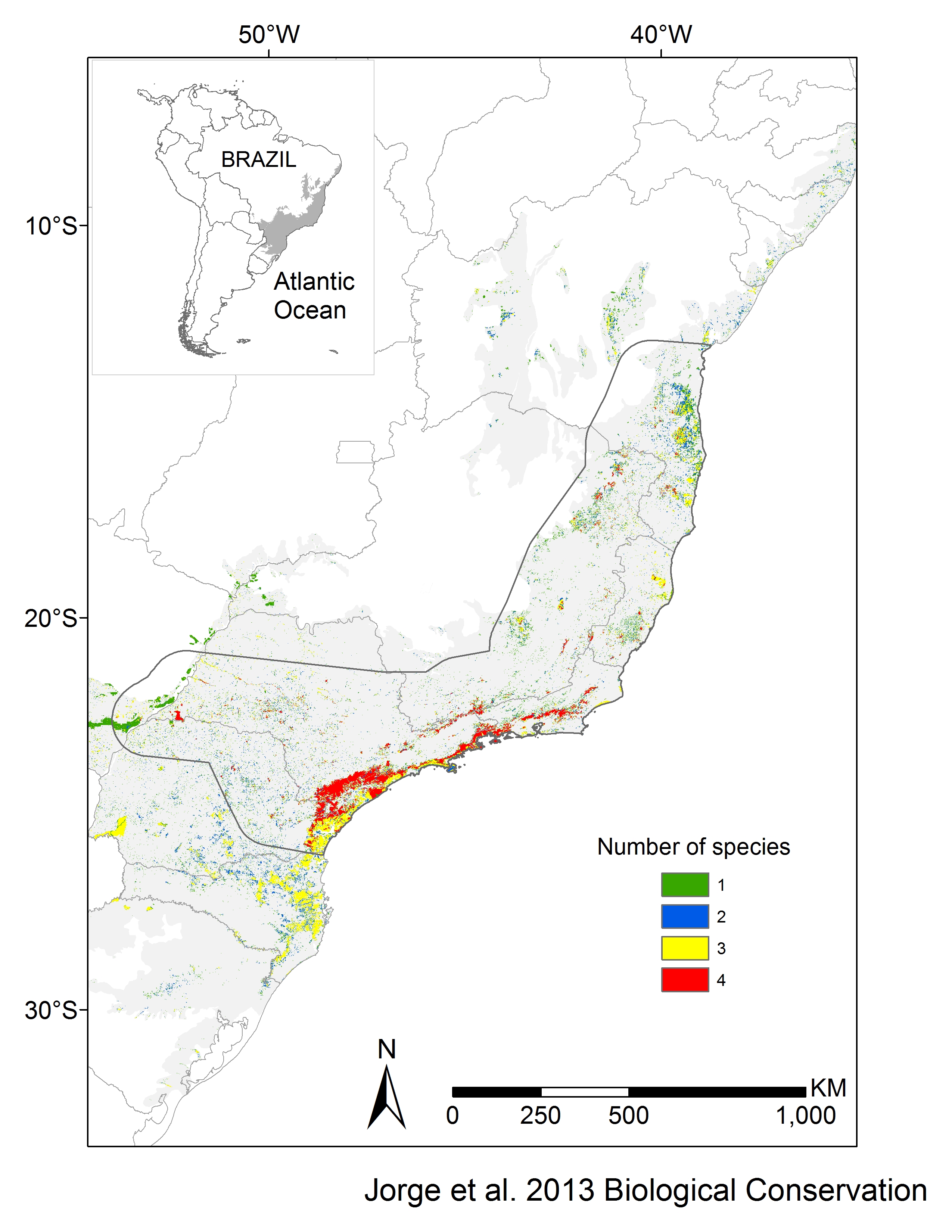

At the regional scale, I use species distribution modeling to map habitat suitability and understand factors that are affecting species presence. I have recently modeled potential distribution of four keystone large mammals (jaguars, tapirs, peccaries and wolly-spider monkeys) in the Atlantic forest.

(Jorge et al. in prep.)

Each species has unique ecosystem role and is highly threatened from human activities. Our results show that most of what is left of the Atlantic rainforest is not suitable for any of the four species, even large and protected tracts of forest.

(Jorge et al. 2013)

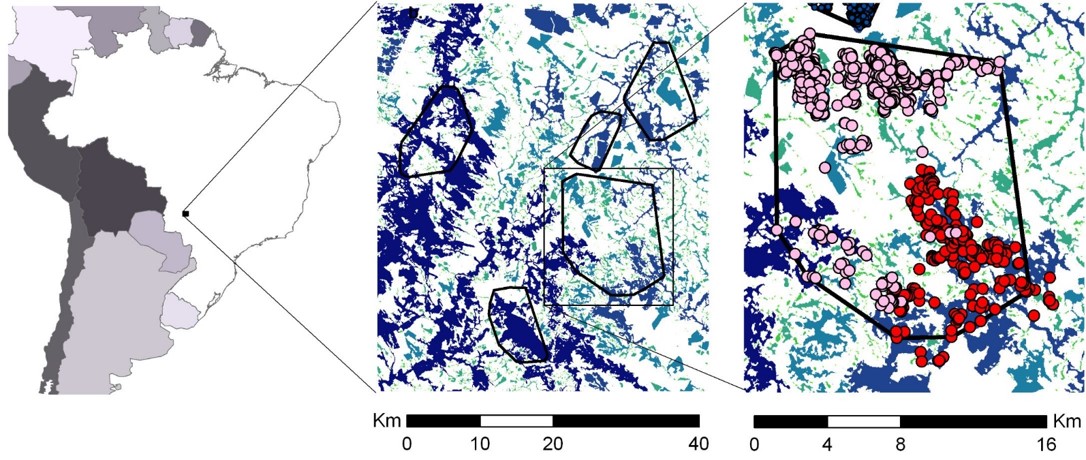

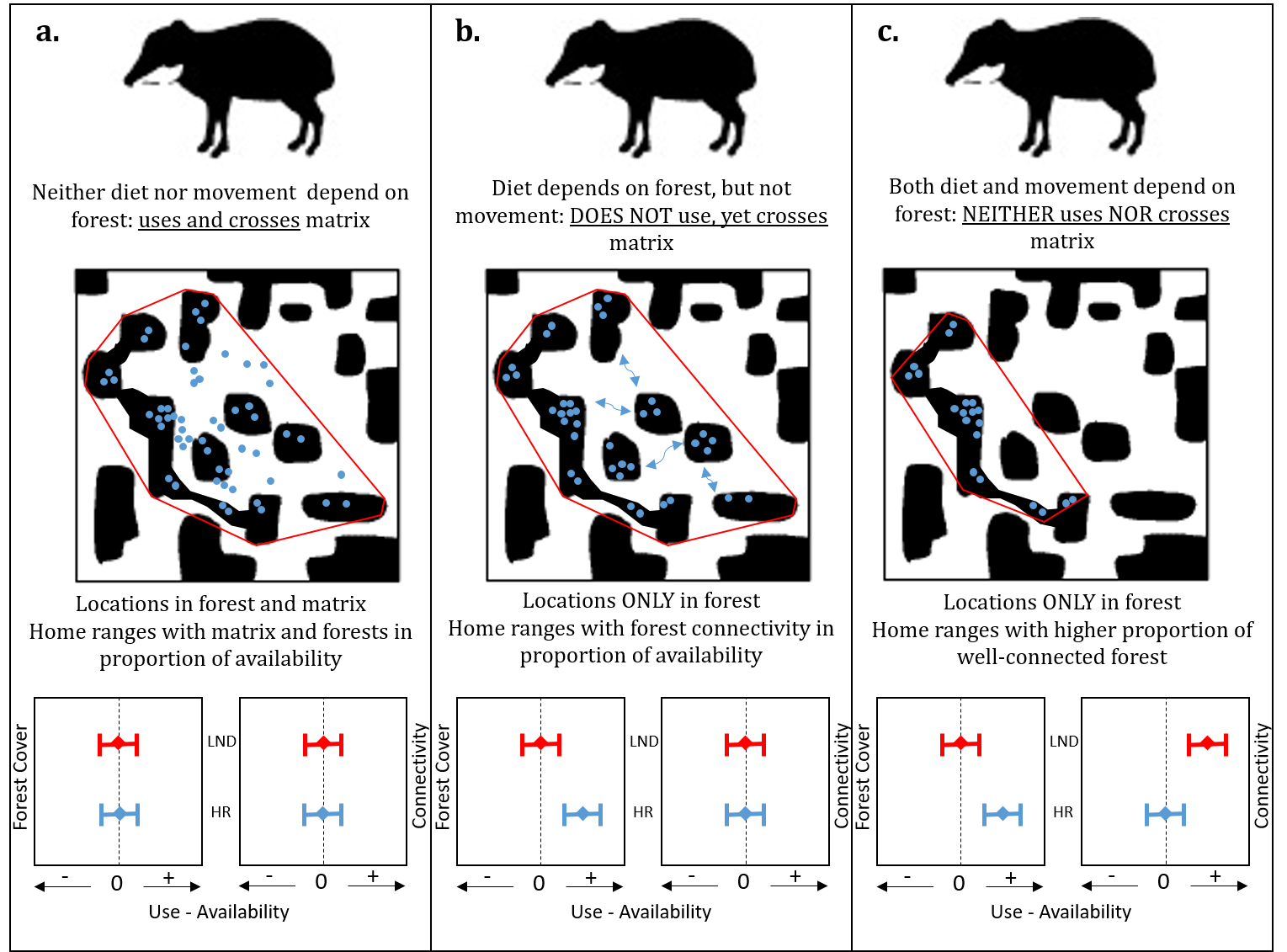

At the local spatial scale, I use radio-telemetry as well as camera-trapping to understand how landscape features (such as proportion of native habitat and connectivity) affect individual movement and habitat selection. I have been working with two species (the white-lipped peccary, Tayassu pecari, and the bush-dog, Speothos venaticus), in two ecosystems: savanna and rainforest.

(Jorge et al. 2019)

White-lipped peccaries are social ungulates (55-80 lbs) are called “ecosystem engineers” because where they forage, they completely change the understory structure and recruitment, affecting ecosystem regeneration dynamics and ultimately patterns of biodiversity. I am using GPS technology to track white-lipped peccaries’ movements and understand their needs at local spatial scale with fine-grained resolution.

(Jorge et al. in prep.)

The bush dog is a rare Netropical small wild dog (7-13 lbs) and the sole in the Neotropics to live in packs. Until the 1990s, there was no information about bush dogs’ ecology in the wild. Since 2004, we have been radio-tracking bush dogs in a region of moderate land use change (Western Brazil). So far we have found that bush dogs are able to move around heterogeneous landscapes, but they are heavily dependent on native habitats and habitat connectivity to move and meet their daily needs. As the proportion of native habitat is converted into croplands and cattle ranches, the area exploited by a pack greatly increases and they become vulnerable to predation by dogs and domestically transmitted diseases.

My future plans include continuing to explore habitat suitability at regional level using species distribution modeling with other species and in other ecosystems. I will also expand the GPS-tracking program with white-lipped peccaries to new areas and new ecosystems. Finally, I plan to use my field-based findings on individual-based models that will help better predict species’ faith in distinct scenarios of landscape change and propose ways to minimize their disappearance and long-term loss of their services to the ecosystems where they live.

Connect with Vanderbilt

©2024 Vanderbilt University ·

Site Development: University Web Communications