Michelangelo’s Signature Art

An Introduction to the Exploratory Study

by Carl Smith

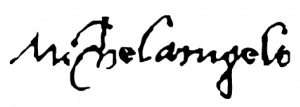

Can you read this familiar example of the great Renaissance artist’s signature? Of course you can, it is Michelangelo’s signature – right? Actually, no, it isn’t. If it were, you might not know whose signature it was, because it would look like this:

A well-meaning graphic artist manipulated this signature to create the one above. Why? So it would have the familiar spelling and you could recognize it: M I C H E L A N G E L O. That’s how we know him, and that’s the name he was given – but that’s not the spelling of it he used.

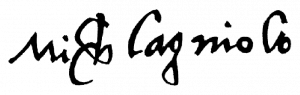

He was named for Michael the Archangel; in Italian, Michelangelo. But for what turn out to be some very interesting reasons, he clung to one of the older Tuscan spellings of his name, Michelagniolo. Nor do his signatures all look the same; he can be quite effusive, and at times even a bit sloppy:

Yet at other times he can be so precise as to appear to be engraving his signature, as in this unusually small example:

But while this small signature is certainly meticulous and eye-catching, it too is, alas, not quite genuine. Apparently the graphic artist was asked by a book’s publisher to retain the artist’s original spelling but do away with the confusing little caprices Michelangelo added at the end of his name; this is how he actually signed it:

It is indeed a shame the signature was altered, because those little gestures have some very interesting, even revelatory, associations.

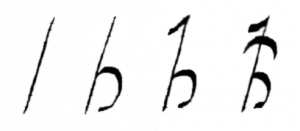

But what is this odd symbol he uses in so many of his signatures, and what does it mean? It is his che, an abbreviation he borrowed from an older style of writing known as mercantesca and adapted for his newer cursive style; it became almost a kind of trademark or logo for him, identifying him both as Michael-Angel and, if subtly, as a son of Florence, where as a boy he was first taught to write in the mercantesca style.

Here is a demonstration (in my hand) of how Michelangelo signed his name using his che, showing first the H (the stem, bulb, and flag that together make it look almost like a backwards musical eighth note), and then the additional, curved E-stroke across the stem of the H (the usual abbreviation for E in mercantesca):

Then all put together:

Writing as he did with quill pens fashioned from crow’s or raven’s tail feathers, Michelangelo could only connect two or three letters before he had to reposition his hand to maintain the necessary angle with the paper. Sometimes the gaps between groups of letters are surprisingly large – larger than is necessary – and he is not consistent with where he puts them. It can seem at times that he means for certain groups of letters to be understood as words themselves, and when read in that way they can be of surprising significance.

Recalling that Michelangelo’s love of wordplay in letters and poems was a source of delight to his friends, we eventually realize that the old Tuscan spelling of his name contains far more concealed words for such play than does the Italian spelling we are accustomed to – and he takes full advantage of them.

Almost all of Michelangelo’s signatures until around 1530 use his che, his Florentine trademark, but after some terribly difficult years in the late 1520s, he began to take longer trips to Rome, where he eventually moved in 1534, never to return to Florence; perhaps he decided that calling attention to his native city while living in a rival one was not helpful professionally. In any event, he began writing out each che as three individual letters and used his che only once in the next thirty years, in a unique and very special circumstance.

* * *

The signature at the top of this page is taken from an April 1525 letter from Michelangelo to his friend Giovanni [della] Spina in Florence.

Connect with Vanderbilt

©2026 Vanderbilt University ·

Site Development: University Web Communications