The Lions’ Mouths

The Lions’ Mouths

by Carl Smith

When finally writing What’s in a Name? after a good many years of studying and considering Michelangelo’s surviving signatures and the contexts in which we find them, it became obvious that some of the more detailed observations on his hand were, while perhaps of considerable interest to calligraphers, not essential to the telling of the story of the signatures, and those I ultimately decided not to include. There are also some signatures in which it seems likely that he is, if not engaging in actual wordplay, nonetheless “playing with” – sometimes quite expressively – the visual appearance of his written name; given all we have seen him do with his pen when signing his name, this should hardly come as a surprise. But these signatures usually involve such small, detailed gestures that they are challenging to write about, and they seldom contribute anything essential to our larger narrative.

But for those signatures I chose to write about, I offered the fullest explanations I could, holding back no relevant details – with just a couple of exceptions. One of those exceptions I want to address now, because I believe it to be so interesting and so revealing of the remarkable depth of Michelangelo’s richly associative thought. My decision to wait before writing about this further level of associative thinking I believe to be revealed on a particular drawing sheet was prompted primarily by a desire not to overwhelm the reader with so many associations that my principal arguments about the sheet became obscured – as well as, frankly, a desire to wait and see how scholars who read the book reacted to it. I also wanted to live a while longer with my observations (some of which were surprising even to me) to see whether, over time, they seemed to weaken in significance.

They have not weakened. If anything, they now seem to me more significant and compelling than before, not less. So I have decided to begin filling in the few gaps I felt I needed to leave when writing the book about Michelangelo and his signatures. I do this with some reluctance and simply because of how interesting and potentially valuable the associations may prove in the long run, and I do it mindful of my assertion at the outset of the study that I intended to avoid discussing works of art not directly linked to his signatures.

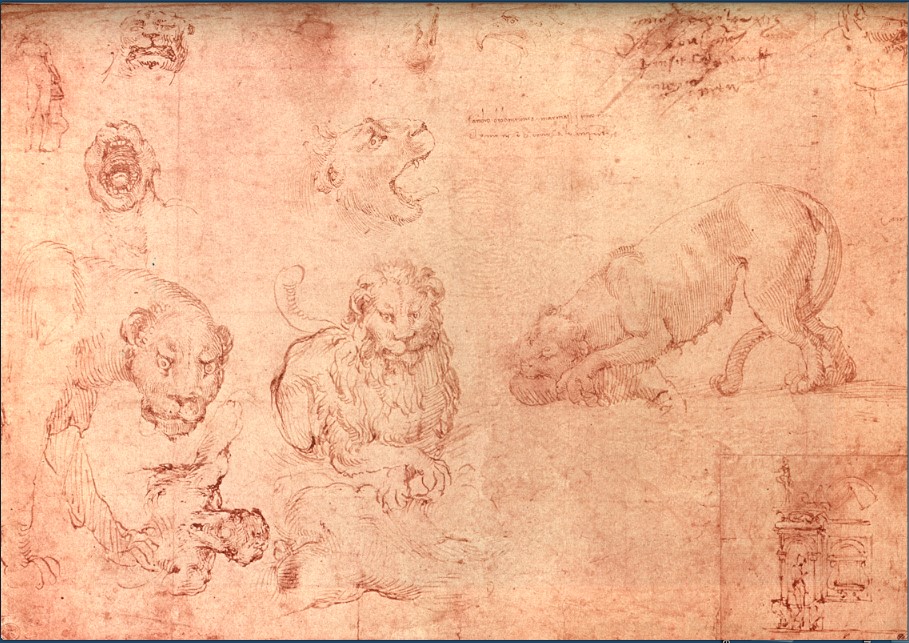

Probably the most significant addition to the book’s text concerns what I have called the Albertina’s “lions” sheet. Perhaps a very brief summary of the book’s discussion of the sheet should be included at this point.

Although de Tolnay accepted (as did many others) its attribution to Michelangelo, the Albertina’s own inventory lists this sheet of drawings of animals (among them several lions), male torsos, etc., as “workshop of Michelangelo.” There is little doubt, in my opinion, that the sheet was his, especially since some of the handwriting in the upper right quadrant is – as I believe I have demonstrated – his. But some of the writing is not his, and there is good reason to doubt that some of the figures are, especially (again, in my opinion) the miniature ones. (We are reminded that the presence of more than one hand on such drawing sheets is hardly remarkable.) Alan Pascuzzi’s suggestion that many of the animals would likely have been drawn from a copybook such as artists kept in their studios to train students and apprentices continues to resonate, and it offers a more-than-plausible explanation for the sheet’s origins. Why it was kept and then altered by the later (likely much later, to judge from the drawing style) addition – directly onto the sheet – of the Michelangelo’s statue of Bacchus in the upper left corner, and of the tomb – as an attachment (or rather as an insert) – in the lower right corner is impossible to say for certain, other than to suggest that the sheet must surely have been important to him in some way.

We saw how the lions, perhaps particularly the one with the widely gaping mouth, could cause us associatively to recall the Offertory Sentence of the Requiem, the mass for the dead, and I offered the suggestion that, as a sort of preconscious subtext, the sheet could be read as dealing with the price of yielding to temptation, perhaps even going so far as to suggest “the wages of sin.” I continue to hold to this view, although I readily acknowledge that the sheet itself is so cluttered, so laden with images that collectively produce what we of today might refer to as “visual noise,” that understanding its narrative with certainty is not possible. On the other hand, given Michelangelo’s demonstrated fondness for carefully constructed ambiguities, this seems to me just the sort of petri dish in which he might choose to cultivate such a metaphorical image, and if one is open to seeing it here, it cannot be overlooked.

But now, to explore another understanding of the sheet – but one which will ultimately, I believe, lead us back to this very same understanding – I would like to consider another of the lions, the one we see in profile, glancing curiously at us out of the corner of its eye as if to be sure we are still looking at it, the one with the almost comically – and anatomically impossible – finger-like tongue. Was its index-finger-like tongue that appears almost to be gesturing to us carefully drawn with that intent, or was it some young artist’s as-yet imperfect technique that gave it that appearance? I suspect the latter, but even if that were the case it would not prevent a later examiner of the sheet – perhaps even the same artist who had drawn it earlier – from seeing it just as we of today see it. (Even when squinting at the sheet through a strong lens, I could not determine whether the tongue had been altered at some point.)

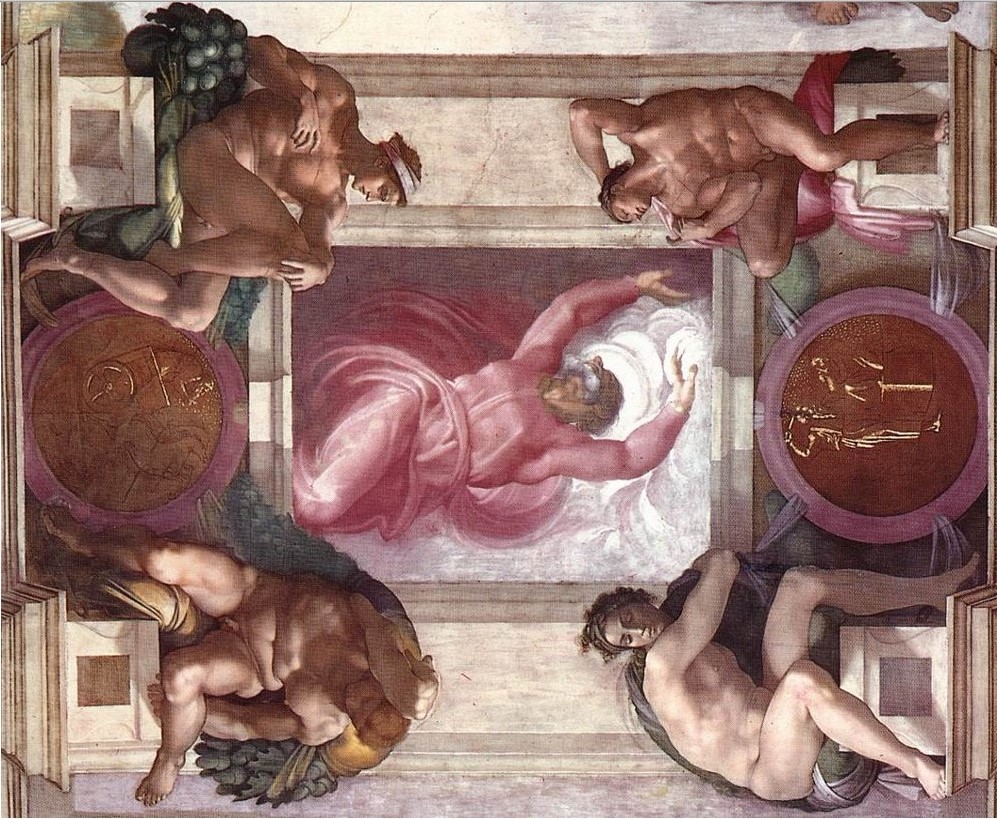

This doubtless seems a lot of to-do over minutiae on a drawing sheet few would call important, but in fact I believe it to be quite important and closely related to another image from Michelangelo’s hand, one no-one would call unimportant, one that also has a finger gesturing in seduction, its subtext also temptation, but one that is seen by thousands of people daily on the ceiling above the altar in the papal Sistine Chapel, in the panel known as “God separating the light from the darkness.”

Let me first hasten to say that I have no intention of undertaking a discussion of the Sistine ceiling – far from it. I only wish to point out certain perceived similarities of subtext between this one particular panel and the Albertina lions sheet. However far-fetched the idea might initially seem, I believe, first, that the two are likely related in some significant ways and, second, that suggesting an approximate chronological correspondence for the painting of the ceiling panel and alterations to the drawing sheet is entirely plausible. Let us remember that Michelangelo made clear to all who would listen that he had no wish to be painting a ceiling – this or any other – but that he wanted instead to be working on the pope’s original commission from him, the carving of his tomb.

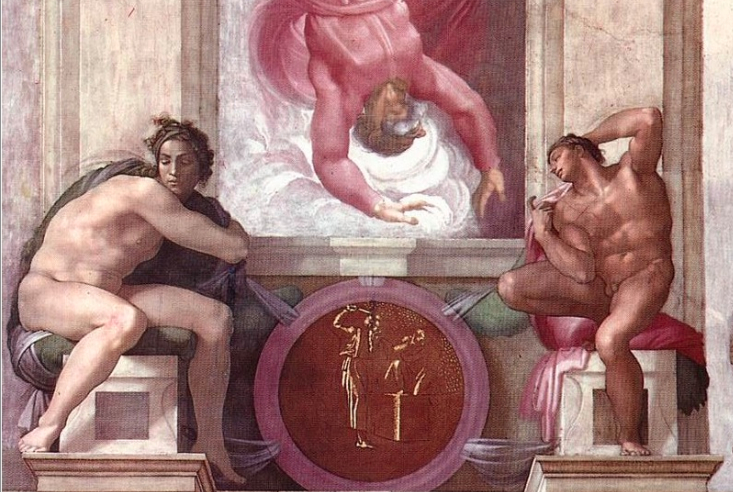

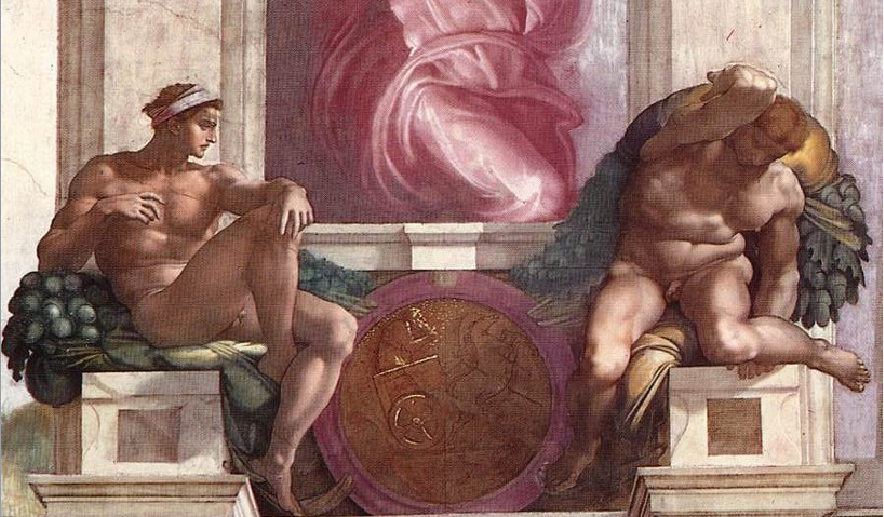

One could easily make a sizable study of the ceiling ignudi, the four nude youths (all of them in unique poses) that surround each of the five “recessed” ceiling panels. Many of the ignudi are presented in poses that would defy even an accomplished and agile gymnast, but these four are different. Of them, only one appears to be struggling in his assigned role, and that seems more because of the burden he has to bear than the pose he has had to assume.

Turning first to the two figures closer to God’s hands, we note that one is presented in what might reasonably be called a lascivious pose – apparent even before we notice the seductive, “come hither” gesture he makes to the other figure with his right index finger. But the object of his intentions is clearly having no part of it; his eyes are lowered modestly and he has turned his head away from the would-be seducer. And he is not alone or unaided in his virtuous response, since God’s right hand and arm seem to be restraining, perhaps even brushing away the would-be seducer, keeping him confined to the darkness while the virtuous figure, who is also shielded by God’s left arm, is surrounded by light in his more virtuous position nearer the altar wall.

Turning next to the two ignudi nearer God’s knees, we find an equally contrasted pair of figures. Both have sizable bundles of oak branches and leaves laden with large, heavy acorns – the emblem of Pope Julius’s family, the delle Rovere. The ignudo further from the altar wall, perhaps the most idealized beauty of the twenty figures, reclines casually in the darkness upon and against his oaken bundle, in a pose worthy of a more modern artist’s studio. With his glamorous looks and condescending pose, he seems to stare almost disdainfully at his fellow ignudo, one who seems bent nearly double under the weight of his own oaken bundle. Michelangelo struggled fiercely under the perceived weight of his delle Rovere burden, much like the virtuous ignudo, the one in the light – and nearer the altar wall. Michelangelo’s admiration for beautiful young men is surely a surprise to no-one today, but he had some harsh words for poseurs and dandies, perhaps most memorably in a scathing poem (JS:75), one whose words might be understood to describe a youth like this haughty, semi-reclining ignudo.1

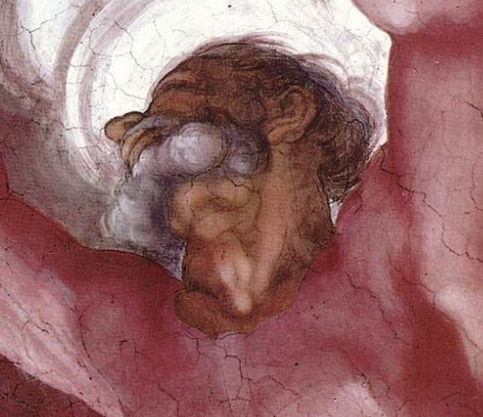

About the figure of God himself in this panel I will offer only two observations. Writing in the professional journal Neurosurgery, two doctors in that field strongly assert that certain features of God’s neck as depicted here are unique in Michelangelo’s work and that they clearly – and accurately – depict specific anatomical structures in the human spinal cord.1 Whether they are correct in this latter assertion I cannot say; I would assume they are. But I do have to question their claim that the representation of the neck structures in the ceiling panel is a unique one, because those same structures appear to be present (and in a similar pose) in the first of the two partial torsos located near the bottom left of the drawing sheet. (It is important to recall that, as is described in detail in the book, the sheet itself is rather small, faded, and challenging to study.)

I have wondered for some time, primarily on the basis of drawing style, whether those two torsos might not also be later additions to the sheet; I suspect they are. And if they are, they may have no relation to the lions just above and were not intended to appear as if being devoured by them; the torsos may merely have been squeezed into available space on the sheet. (Then again, the visual association may have been intentional even if the torsos were added later.) In any event, the similarity of the detailed structures in the neck, especially as revealed in a pose similar to that of the ceiling’s God figure, further increases the likelihood of some connection between these two fascinating panels (the fresco and the drawing sheet), regardless of the exact chronology.

This Sistine panel is sometimes spoken of as autobiographical, for a variety of reasons. I have little desire to challenge that suggestion; in fact, in support of it I will mention one especially curious detail. Michelangelo was, of course, famous for (and apparently ashamed of) his curiously flattened nose, which he claimed had been broken in an adolescent scuffle with a sculptor jealous of Michelangelo’s greater talent. But as any attentive viewer can easily determine, God’s (or Michelangelo’s?) nose as depicted here is anything but flattened, it is a schnoz of epic length and girth, while the nose of the figure in the drawing is flattened. Why would the Sistine figure, whoever he is (perhaps on some level both God and Michelangelo?), have been saddled with such a monster, if not to guarantee that from the chapel’s floor so far below it would prove too notable a nose to go long unnoticed?

1 May, 2010; I. Suk and R. Tamargo [return to text]

© 2015 Carl Smith

Connect with Vanderbilt

©2024 Vanderbilt University ·

Site Development: University Web Communications