Home » News » A Residential College Memory

A Residential College Memory

Posted by Douglas Fisher on Wednesday, November 2, 2016 in News.

Last year I attended the Second Residential College Symposium (RCS) at Southern Methodist University (SMU), and this year the Vanderbilt Commons hosted the third in the series. I presented with Matthew Sinclair and Jim Lovensheimer on our collaboration at Warren and Moore colleges (WaM); had the great pleasure of talking to Rishi Sriram, Faculty Steward of Brooks Residential College at Baylor University, who impressed the heck out of me at the SMU conference; and I did some catching up with Eric Kaufmann, Faculty Principal of Honors Residential Commons (HRC) at Virginia Tech, who visited Warren and Moore with HRC students last year, and who influenced me too. I wish that I could have attended more this year, but home turf demands and conference travel preparation played out inconveniently.

I met some residential faculty colleagues this year for the first time too, including the Provost of Merrill College at UC Santa Cruz, Elizabeth Abrams, and the Provost of Cowell College, Alan Christy, also of UC Santa Cruz. I was excited to meet them. I attended Stevenson College of UCSC as a freshman from 1975-76. Elizabeth suggested in a Faculty cohort meeting at the Commons-hosted RCS that its the residential college that is the dominant identity for many from UCSC, and so it is with me.

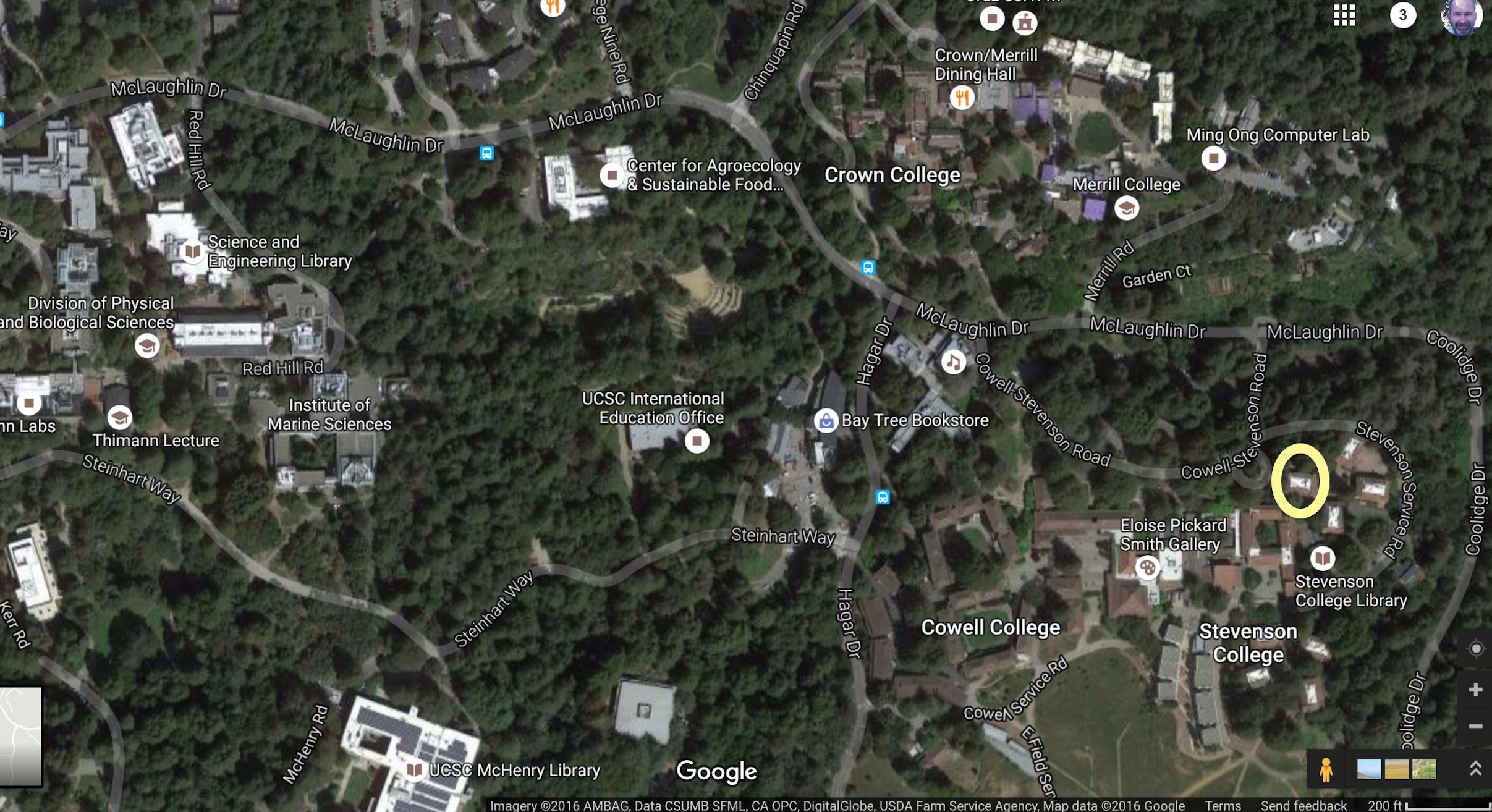

I lived in the upper quad of the Stevenson dorms, in the dorm encircled in yellow in the image. Our dorm was all first year students, with women on the first floor, men on the third floor, and men and women on the second floor; there was a single central, shared restroom and laundry space on our floor, and presumably other floors too. For Vanderbilt folks, my dorm was the “mini Commons” for the upper quad. I still remember leaving my parents’ house in Glendora, CA, in my VW bug, with a trunk (that is now in our closet at Warren 503!) in the back seat, driving up US 101, carrying the trunk upstairs to my third floor room, and meeting my roommate, who was from Oklahoma, for the first time.

Elizabeth and Alan said that the college provosts were interested in the stories that alums had to tell, and so I will tell one. They seemed interested that I remembered so much about my Stevenson College core course. I rattled off the readings for them (Pirsig, Kafka, Nietzsche, Dostoevsky, Malcolm X, Sartre, Marx and Engels), as part of a discussion that followed Elizabeth’s question to Jim Lovensheimer and me about curricular offerings by Warren and Moore colleges (of which there are none yet).

“Stevenson 1”, the 5-credit college core course, was required of all first year students. In those days all UCSC courses were 5 credit hours, and everyone was expected to take three courses. Instead of letter grades, there were end-of-semester written evaluations by instructors. I remember that my section of Stevenson 1 convened, perhaps daily, in the first floor lounge of my dormitory. I have vague impressions of being seated in a circle, with my section of perhaps 10 students, talking amongst ourselves and the instructor on the readings.

I still have four reports that I prepared for the Stevenson 1 course, but I am sure that I had not laid eyes on them since I last moved offices in Computer Science at Vanderbilt — about 15 years ago. Nonetheless, I could point to the significance of the readings in my life, even before I went through my reports again the other day. Stevenson 1 was clearly a course on individual identity in society.

The reports, with erasures and cross outs, were written on my manual Olympia typewriter, which is now in my Computer Science office’s micro-museum of technology. The dates of the reports and name of instructor are given too (“Oct. 13, 1975”, “Mr. Lindsey”; “Oct. 27, 1975”, “Mr. G. Lindsey”; “Nov. 12, 1975”, “Mr. Glen Lindsey” (first name misspelled); “December 3, 1975”, “Glenn Lindsey”).

I am glad that by the end of the quarter, I was comfortable identifying Mr. Lindsey by his first name. I found him by Web search very easily. His bio in the second column of this newsletter suggests Mr. Lindsey as an exemplar of a humanities student succeeding in business because of the strengths of a humanities education. This is an emotion-tinged personal find after 40 years.

Mr. Lindsey’s comments are on the reports. On my first report on Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, he was effusive, “almost speechless”, concluding with “I expect the other papers to be as good and to hear more from you in class.” My father was very proud of that paper, and for what seemed like several years, my younger brother had a favorite line from my paper that he would quote in a theatrical tone, and then laugh. They both read the book and discussed it together as they read. We talked about the book when I returned home on break.

In my second report, I compared Nietzsche’s “superman” and Dostoevsky’s the Grand Inquisitor. Mr. Lindsey wrote that it was “certainly well written” (“certainly”) and the thesis was original, but that I spent “too much time on plot summary and paraphrase” so that my interpretation suffered. After other comments he concluded with “This is a good paper, however.” I can only imagine now that this more tepid response was a letdown. But The Grand Inquisitor, in particular, has stuck with me all these years. Just last year, I suggested to a colleague, and faculty facilitator of a film as a part of Vanderbilt’s International Lens series, that there were interesting parallels between Dostoevsky’s parable and “The Heavenly Creature”, a vignette from the film. I delved back into the text, which I still have, to support the argument. She seemed to love the parallels. Perhaps this reading of many years ago will find its way into a work of scholarship one day, and in any case, it has contributed to an enthusiastic connection between colleagues.

The third paper on Kafka’s The Trial received a “Good job” and a comment on the mismatch between the opening thesis and what I actually developed in the paper, on the carelessness and hiding-in-plain-sight brutality of bureaucracy. This paper received many more in-text comments from Mr. Lindsey than any of the other three. When Kurt Vonnegut spoke at Vanderbilt almost 30 years ago on the shape of stories, he graphed prototypical Kafka on stage at Langford Auditorium, with a line graph that started deep in the negative region, continued level for a time, and then went to “negative infinity” — I laughed loudly, but only because I had read The Trial and saw its truth in my own life. What I remember so exactly from the novel is the parable of the man from the country. I have replayed it many times. Its a story of how the fear of breaking with the traditional, hidden, and insidious practices towards individuals in a bureaucracy shames the soul. And of course, the fear that eclipses the “courage to change the things I can” can kill the body too.

With the final paper on The Autobiography of Malcolm X, I may have returned to the heights I achieved with the first paper, at least in Mr. Lindsey’s eyes. What a great book to conclude a course that spent much time on the repression of individuals by societies. Malcolm X was a remarkable man, who transformed profoundly — not once, not twice, but three times or more. He exemplified the superman of earlier writers, not born to it, but always evolving as a step function. He was the real-life antithesis of the man from the country. Malcolm X became a personal archetype. While I have taken many small steps along the up-and-down staircase function of my life, I am thankful for the one large step that is comparable with Malcolm X’s exemplars.

While I have had many good courses, and many great-course moments, the Stevenson 1 course ranks with the very few of my most impactful courses. The two others, of which I am aware, are computer Data Structure Techniques from Thomas Standish, and the psychology of Memory and Cognition from Tarow Indow, both at UC Irvine. I took those two courses concurrently, which I am certain added to their impact. I believe that Stevenson 1 may have influenced some life choices, but mostly it gave me frameworks for reflecting on the actions I would have done anyways, and the consequences that followed. And while I remembered Mr. Lindsey little over these many years (as I remember now, because one must remember that one remembered too), I have reread his comments, more extensive than what I summarize here, and I am thankful for his gracious presence in my life. What a great mentor he was, and I was not conscious of it.

I left UCSC after 2 quarters, but through no fault of UCSC or Stevenson College. UCSC had been my father’s dream school, not mine, and I think I needed more structure than the freedom that UCSC afforded. I am now struck by the irony of that desire for structure given the nature of the Stevenson 1 course, and my desire for structure in the face of my rebellion against paternal influence. I went instead to the United States Naval Academy (USNA) for two years. Though there were differences between the two schools that are predictable, they are both residential college systems, intended to establish lifelong bonds. I maintained friendships at each. My best friend at UCSC, who turned me (and my brother) on to the Grateful Dead, now plays an important role at UCSC. After two years at USNA, perhaps emboldened by Malcolm X, I moved again, to UC Irvine, largely a commuter campus with a middle-of-the-road political temperament, to finish my undergraduate degree in computer science, and where I stayed for graduate school.

I have many fond memories of Stevenson College and UCSC. Its been fun and instructive to relive the one. Returning to Elizabeth’s original prompt, in an upperclass, residential college like Warren College at Vanderbilt, I can imagine college-specific courses too, though not required and not 5 credits! At Vanderbilt, the Commons’ reading and year-long discourse plays much the same role as Stevenson 1, and is probably potentially as profound to our students as Stevenson 1 was for me.

Moreover, in the Vanderbilt setting, a seminar in an upper-class college would encourage exploration of out-of-the-box course designs by instructors. It does so at the Commons. I have taught three first-year 1-credit seminars that I recall; one was a gentle introduction to computer science, but the latter two were on computing and environmental sustainability, which preceded my upper division special topics courses at the nexus of those fields. With the advent of University Courses, the exploratory niche of residential college courses may be diminished, but not eliminated. I dream of a seminar in one of the Warren common spaces on Art of the Data Structure, for example, which brings together students from art, computer science, and all disciplines, to visually and stylistically represent disciplinary and societal content as it is formatted and processed “inside” the computer (e.g., think about the dance that happens inside the computer when doing a Google search for the Yellowstone caldera or the presidential election). Perhaps the first instance of such a seminar or “gathering of minds” will be not-for-credit, with incentives other than grades, like a public exhibit or a publication. Its probably a stretch to assume that students would do it for fond memories 40 years hence! But one advantage to living this long is that I know the power of those memories, and I can hope to meet students where they are, and ensure that there is the possibility of the experience.

I appreciate that Elizabeth, Alan, and RCS triggered the reflection. Thanks to all, including my instructor of 40 years ago.

Doug Fisher is Faculty Director of Warren College. The opinions expressed herein are Doug’s, and are not necessarily the opinions of Vanderbilt University.

©2026 Vanderbilt University ·

Site Development: University Web Communications