Jeff Sessions Rescinds Obama-Era Enforcement Guidance: Five Observations

[Post has been updated and revised again to add new links: Jan. 12, 2018]

On January 4, 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions formally rescinded enforcement guidance that had been issued by the Obama Administration DOJ as far back as 2009. To simplify somewhat, that guidance had urged United States Attorneys not to enforce the federal marijuana ban against individuals who comply with state law, unless those individuals implicated some federal enforcement priority (e.g., by distributing marijuana to minors). The guidance – including the Cole II memorandum of 2013 – is discussed in the book at pages 343-353.

Here are the most relevant portions of the Attorney General’s brief statement:

“Congress has generally prohibited the cultivation, distribution, and possession of marijuana. . . . [The prohibitions and corresponding sanctions] reflect Congress’s determination that marijuana is a dangerous drug and that marijuana activity is a serious crime.

In deciding which marijuana activities to prosecute under these laws with the Department[ of Justice’s] finite resources, prosecutors should follow the well-established principles that govern all federal prosecutions. Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti originally set forth these principles in 1980, and they have been refined over time, as reflected in chapter 9-27.000 of the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual. These principles require federal prosecutors deciding which cases to prosecute to weigh all relevant considerations, including federal law enforcement priorities set by the Attorney General, the seriousness of the crime, the deterrent effect of criminal prosecution, and the cumulative impact of particular crimes on the community.

Given the Department’s well-established general principles, previous nationwide guidance specific to marijuana enforcement is unnecessary and is rescinded, effective immediately. . . .”

The full announcement (it’s only 3 paragraphs) can be found here.

Let me share five observations about the announcement.

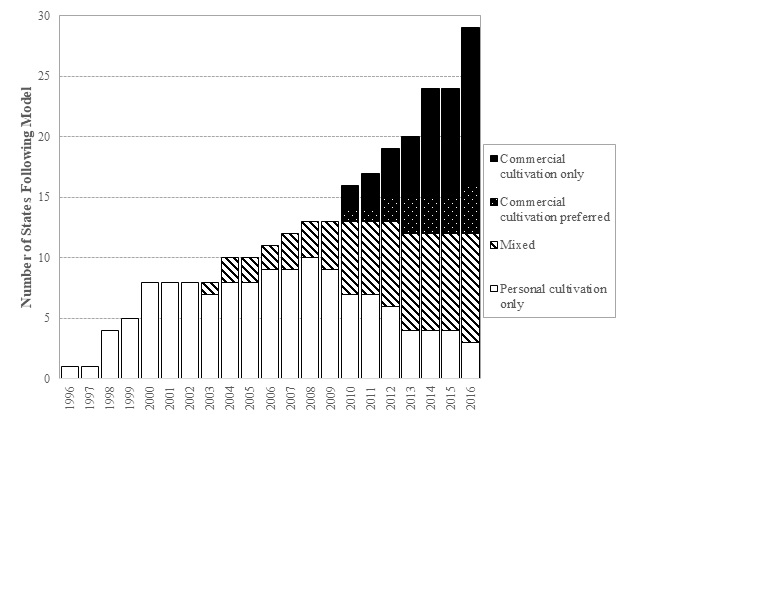

1. The guidance that was rescinded was critical to establishing the commercial marijuana industry that exists today. Before the first guidance (the Ogden memorandum) was issued in 2009, only a few states had explicitly authorized the commercial supply of marijuana. Up to that time, most states that had legalized (medical) marijuana expected consumers to grow the drug themselves or to have a caregiver do it (what I call the personal supply model). Even though many states thought that commercial suppliers would do a better job of meeting patient needs, they feared that large-scale commercial suppliers would be easy prey for federal law enforcement. But when the Obama Administration issued the Ogden memorandum in 2009, states perceived it as a green light and quickly embraced the commercial supply model, as shown in Figure 10.1 from my book (page 532):

The four models of supply are defined in the book on page 480. Under the personal only model, commercial cultivation and distribution are not allowed. The other models – including mixed – allow commercial cultivation and distribution, or even make that the exclusive mode of supply (the commercial only model). Indeed, by the end of 2017, all 30 states (plus D.C.) with medical marijuana laws had authorized the commercial production and distribution of the drug – a huge jump from the three that had done so as of 2008.

2. Nonetheless, the commercial marijuana industry can likely survive today without the rescinded guidance. The industry is bigger and more geographically dispersed than it was back in 2008. By the end of 2017, all 30 medical marijuana states (plus D.C.) had authorized the commercial production and distribution of medical marijuana – by contrast, only 3 states had done so as of 2008. There are already several thousand – as a rough estimate, perhaps 5,000 – state-licensed marijuana suppliers in operation across these states. The cat is out of the bag, so to speak, and putting it back in would not be easy, for reasons I’ve explained in this Article.

For one thing, U.S. Attorneys don’t have enough resources to wage an effective campaign against the marijuana industry (at least in some states). Colorado alone has over 600 licensed marijuana suppliers. Second, for a variety of reasons (e.g., a desire to seek local elected office in the future), those U.S. Attorneys don’t want to alienate local constituencies. This means they occasionally must put local preferences ahead of the preferences of the Attorney General (or their own). For example, a U.S. Attorney who aspires to elected office in California someday would likely think twice before initiating a crackdown on the local marijuana industry.

Indeed, the Attorney General is not even pressuring these U.S. Attorneys to start a crackdown. Although the Attorney General’s announcement labels marijuana activity “a serious crime”, he did not explicitly urge U.S. Attorneys to prosecute anyone. Instead, he indicated that enforcement decisions would be left to their discretion. And interestingly, the Attorney General strongly hinted that those U.S. Attorneys could exercise that discretion the same way they had under the Obama Administration guidance he just rescinded. That is how I read his statement that the guidance was being rescinded because it was redundant with guidance found in the U.S. Attorney Manual – i.e., the marijuana guidance was unnecessary and not necessarily wrong. Notably, the U.S. Attorney for Colorado has already announced that his Office’s would stay the course post-rescission:

“Today the Attorney General rescinded the Cole Memo on marijuana prosecutions, and directed that federal marijuana prosecution decisions be governed by the same principles that have long governed all of our prosecution decisions. The United States Attorney’s Office in Colorado has already been guided by these principles in marijuana prosecutions — focusing in particular on identifying and prosecuting those who create the greatest safety threats to our communities around the state. We will, consistent with the Attorney General’s latest guidance, continue to take this approach in all of our work with our law enforcement partners throughout Colorado.”

(The Colorado U.S. Attorney’s announcement can be found here.)

3. Nevertheless, the rescission announcement could exacerbate one problem for the marijuana industry. Namely, it will likely make it even more difficult for the industry to obtain banking services. For reasons discussed in the book (pages 681-696), banks have been reluctant to serve commercial marijuana suppliers. One piece of Obama Administration guidance from 2014 (Guidance Regarding Marijuana Related Financial Crimes) was designed in large part to allay the concerns of banks and thereby boost access to banking services for the marijuana industry. The Attorney General’s announcement on January 4 rescinded that guidance, as well as the guidance regarding prosecution of the marijuana industry itself. While some banks had started to serve the marijuana market (see my earlier post here), the rescission might cause some banks to retreat from it.

It is worth noting that the Attorney General did not — and probably could not — rescind guidance issued by the Treasury Department in 2014 regarding the Bank Secrecy Act and Marijuana Related Businesses (see here). However, I wonder whether that guidance – which simplifies the reporting requirements for banks that serve the state-licensed marijuana industry – can remain in effect, given that it explicitly references other now-rescinded enforcement guidance (like the Cole II memorandum of 2013).

4. The rescission may cause Congress to strike back against the DOJ. The Attorney General’s announcement has already triggered a backlash from lawmakers, with several members of Congress criticizing (to put it mildly) the rescission. The Cannabist has a useful collection of lawmaker reactions to the announcement here.

For the last 20 years, Congress has largely been content to let the Executive branch sort out the messy conflict between its statutes and state reforms. But if the DOJ renews enforcement of the federal ban, it might prompt Congress to take action. For example, Congress could bar the DOJ from spending funds to crack down on the recreational marijuana industry, the same way it has barred the agency from cracking down on the medical marijuana industry. (Those restrictions are discussed in the book at pages 353-358 and in this Article.) Passage of more substantive reform, like repeal of the marijuana ban itself, is also a possibility, but a far less likely one.

5. There are some steps states could take to protect themselves from a potential crackdown. I’ll write more about these later, but let me briefly note 2 options for the states. One is to continue to regulate the industry closely, e.g., to prevent diversion across state lines and distribution to minors. As noted above, preventing these sorts of actions likely remain federal law enforcement priorities (the principles of federal prosecution, found in the United States Attorney’s Manual), just as they were under the Obama Administration marijuana enforcement guidance. It stands to reason that effective state regulations of the marijuana industry will continue to lessen the perceived need for federal law enforcement intervention and thereby the likelihood of a federal crackdown.

Second, states could create a legal defense fund for licensees in the marijuana industry. I elaborate on this proposal in this Article. In a nutshell, the state would promise to pay the legal expenses of any state-licensed company that is targeted by the DOJ. The program, which could be funded by state marijuana taxes, would obviously help defray one (potentially large) expense faced by the marijuana industry. But it might also deter the DOJ from pursuing legal actions in the first instance. After all, if the DOJ knows that a prospective target will put up a vigorous defense, it might be less inclined to initiate legal action.

That’s my initial (revised and simplified) reaction. Here are some additional sources providing analysis of the rescission decision:

- Alicia Wallace, What Now? Experts and Politicians Weigh in On Potential Impact of Sessions’ Rollback of Marijuana Policy, The Cannabist

- Robert A. Mikos, Risky Business? The Trump Administration and the State Licensed Marijuana Industry, 2017 U. Ill. L. Rev. Online (2017) (my analysis explaining why a crackdown is unlikely remains relevant today)

- Robert A. Mikos, A Critical Appraisal of the Department of Justice’s New Approach to Marijuana Enforcement, 22 Stanford Law & Policy Review 633 (2011) (my analysis of the original Ogden memorandum provides some useful background on the rescinded guidance and explains its shortcomings)

- Sam Kamin, Jeff Sessions’s New Pot Policy: What Happens Now?, The Hill

- John Hudak, Why Sessions is Wrong to Reverse Federal Marijuana Policy

- The Hoban Law Group, After Sessions Takes Off the Gloves, the Legalized Cannabis Industry Strikes Back

- Doug Berman, U.S. Attorney for Oregon Expressing “Significant Concerns About the State’s Current Regulatory Framework”, Marijuana Law, Policy, and Reform