Research Interests

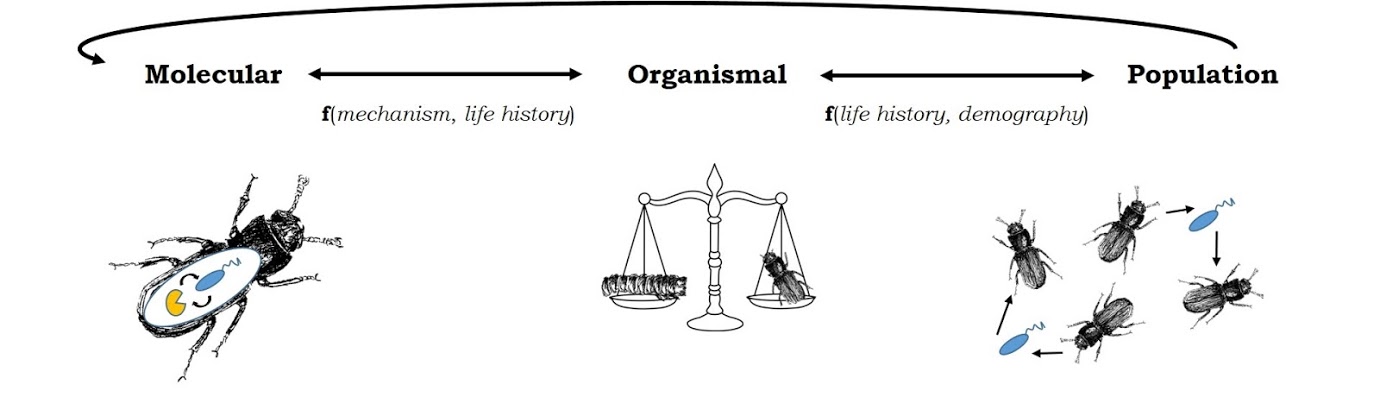

Immune system optimization in a variable world

What should an optimal immune system look like? The answer is, generally, “it depends.” It depends upon the types of microbes that a host is likely encounter, how often it has to face them, how much energy that immune response requires, and how much damage that immune response is likely to inflict upon the hosts’ own tissues. The underlying genetic architecture of the recognition, signaling, and effector networks that allow a host to deploy an appropriate immune response are similarly shaped by evolutionary constraints, including pleiotropy and genetic trade-offs with traits like survival and reproduction.

We are currently pursuing several research foci dedicated to bridging the knowledge gap between what we think an optimal immune system should look like and why immune systems in real organisms often (usually) defy these predictions.

Fundamental questions that we address include:

- If immune systems have been evolving in the presence of pathogens for millions or even billions of years, why do we still get sick?

- How does the environment and other microbes that a host experiences over the course of its life influence its susceptibility to a focal infection?

- What are the costs and constraints associated with deploying an immune response, and how do they feed back on the selective pressures that shape immune system genes, networks, and temporal dynamics?

- Can differences in immune system genes among populations, species, and even broad taxa (e.g. plants vs animals) provide clues toward understanding the complexity of immune systems across the tree of life?

You can read more about our specific research avenues below. We are currently accepting applications from students and postdocs who want to using biochemistry, genomics, and/or theory approaches to address research avenues related to the evolution of pleiotropy, signaling, metamorphosis, or coinfection.

Genetic pleiotropy in immune systems

CURRENTLY RECRUITING IN THIS AREA! Pleiotropy, where one gene affects multiple discrete traits, presents an interesting puzzle for evolutionary biologists because mutations that are adaptive for one trait could antagonize the function of another. Recent analyses in humans have identified immune system genes as particularly enriched for pleiotropic roles in other processes like development and neuronal function. This seems problematic because parasites often target immune genes for manipulation, leading to the expectation that immune genes would have to rapidly adapt to keep up the arms race. Developmental genes, meanwhile, are famously slow to evolve because any mutations could inflict catastrophic consequences on embryos. If selection cannot act on immune phenotypes without affecting the genetic basis of other important traits, could pleiotropy selectively constrain the evolution of immune systems?

What we’ve discovered so far:

- Two-thirds of genes involved in innate immune signaling pathways contribute to both organismal development and immune responses in an insect model (Williams et al. 2023). Under the hypothesis that immune and developmental functions might be under very different modes of selection – pitting adaptation to parasites against conserving developmental programs – we discovered that pleiotropic genes are indeed under stronger purifying selection than non-pleiotropic genes, particularly if they are broadly expressed across life stages. This suggests that pleiotropy does constrain the evolution of immune genes. Does this constraint influence the trajectory of host-parasite coevolutionary outcomes?

- Our coevolutionary models suggest that pleiotropy distorts the fitness landscape of immune signaling networks, allowing for more rapid evolution of highly fit inducible signaling dynamics over solutions with fewer mutational steps but lower fitness (Martin and Tate 2023). The models also predict that non-pleiotropic networks are less robust to parasite manipulation, leading to higher fitness variance and thus lower geometric mean fitness than pleiotropic networks. As a result, pleiotropic networks generally outcompete non-pleiotropic ones (Martin and Tate 2024).

- We quantified pleiotropy in orthologs across six model multicellular eukaryotes (Martin and Tate BioRxiv 2024). Contrary to our initial predictions, we discovered that older genes are just as likely as middle-aged genes to be pleiotropic, and that gene duplication did not necessarily relieve the burden; these patterns were broadly consistent across very different species. Interestingly, immune genes scored higher than other traits in the level of pleiotropy, suggesting that there is indeed something unique about immune system evolution that promotes pleiotropy.

Taken together, these studies suggest that pleiotropy constrains immune system evolution at the gene level but enables robustness to parasite manipulation at the network level. Stay tuned for more to come!

Metamorphosis and the evolution of immune investment

CURRENTLY RECRUITING IN THIS AREA! The trade-off calculus of immune investment becomes complicated when the relative costs and benefits of immunity fluctuate over the ontogeny (birth to old age) of an individual. For organisms that continuously grow and develop, selection for immune investment at one stage of life could force suboptimal investment in other stages. Most animals (in terms of species diversity and abundance) are not continuous developers, however, but instead undergo some form of metamorphosis, allowing them to separate the control of their immune systems in each life stage. We have recently begun projects in both insects and frogs to understand how development versus ecology drives stage-specific immune responses. Stay tuned for results!

What we’ve discovered so far:

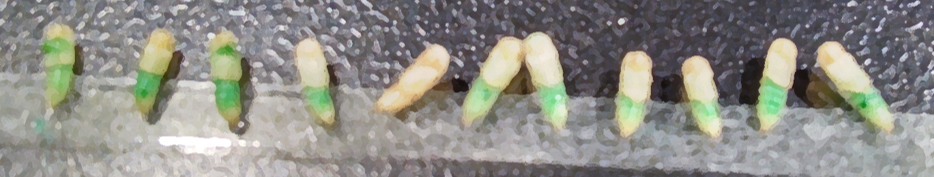

- Even though all flour beetle (T. castaneum) life stages live in their food medium and thus share a similar ecology, they show stark differences in the regulation of immune genes as they progress from larvae to adults (Tate, Perry and Jent 2021), which is correlated to stage-specific resistance to bacterial infection.

- Immune responses that larvae induce against gregarine infection can persist into adulthood even after they clear their infection. Many of these induced immune genes show different forms of co-regulation with other immune genes in each life stage (Critchlow, Norris, and Tate 2019).

Tribolium pupae injected with dye and dsRNA

The evolution of regulation in immune signaling networks

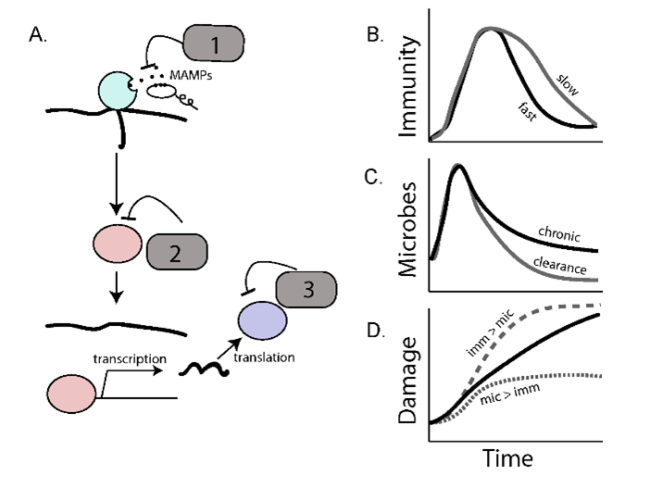

From an evolutionary perspective, optimal inducible immune responses are those that turn on quickly to clear a detected infection and then turn off quickly to avoid the energetic and immunopathological costs of maintaining unnecessary responses. Interestingly, signaling pathways both within and across species use multiple negative regulators to control the flow of information across recognition, signaling, and effector steps of an immune response (Lazzaro and Tate 2022). We are taking advantage of variation in these regulatory “motifs” – that is, what step of the pathway they target, whether they are under control of feedback loops, and whether they are (for example) degrading proteins or competing with them for binding – to understand the evolution of the “turn it off” response.

The role of negative regulators in modifying the costs and benefits of immune regulation. Adapted from Lazzaro and Tate 2022.

What we’ve discovered so far:

- Our stochastic models predict that negative regulators that act upstream vs downstream in a signaling pathway contribute differently to transcriptional noise in signaling output, and only by having both can noise be controlled against different types of pathogens (Asgari and Tate BioRxiv 2024a).

- Our agent-based model of signaling network evolution predicts that downstream negative feedback loops should almost always evolve – and evolve slowly – while upstream ones are dependent on the predictability of pathogens. Consistent with this prediction, preliminary genomic analyses across a variety of animals suggest that downstream negative regulators have smaller and less variable evolutionary rates than upstream regulators (Asgari and Tate BioRxiv 2024b).

- Variation in the efficacy of negative regulators can move the dial on phenotypes associated with the trade-off between pathogen resistance and immunopathology. We discovered that knockdown of cactus, a negative regulator of the insect Toll pathway, does improve resistance to infection but at a substantial and convex-shaped trade-off with development, fecundity, and gut cell regeneration (Critchlow et al. 2024). We are currently combining mathematical models with expansive RNAi experiments in multiple immune signaling pathways to test the prediction that the shape of the trade-off is steeper for pleiotropic and downstream regulators relative to upstream regulators – stay tuned for new results!

The role of coinfection in dynamics across ecological scales

Parasites modulate host population dynamics through their effects on growth rate and mortality, and can even reverse the outcome of competition among multiple host species. In natural populations, organisms usually suffer exposure to more than one parasite at a time (Tate 2019). We are currently investigating how co-infecting microbes influence immune dynamics and infection outcomes in an experimental system; at the same time, we are combining theory and experiments to understand how natural variation in these within-host dynamics affects processes at the population and community levels of biological organization.

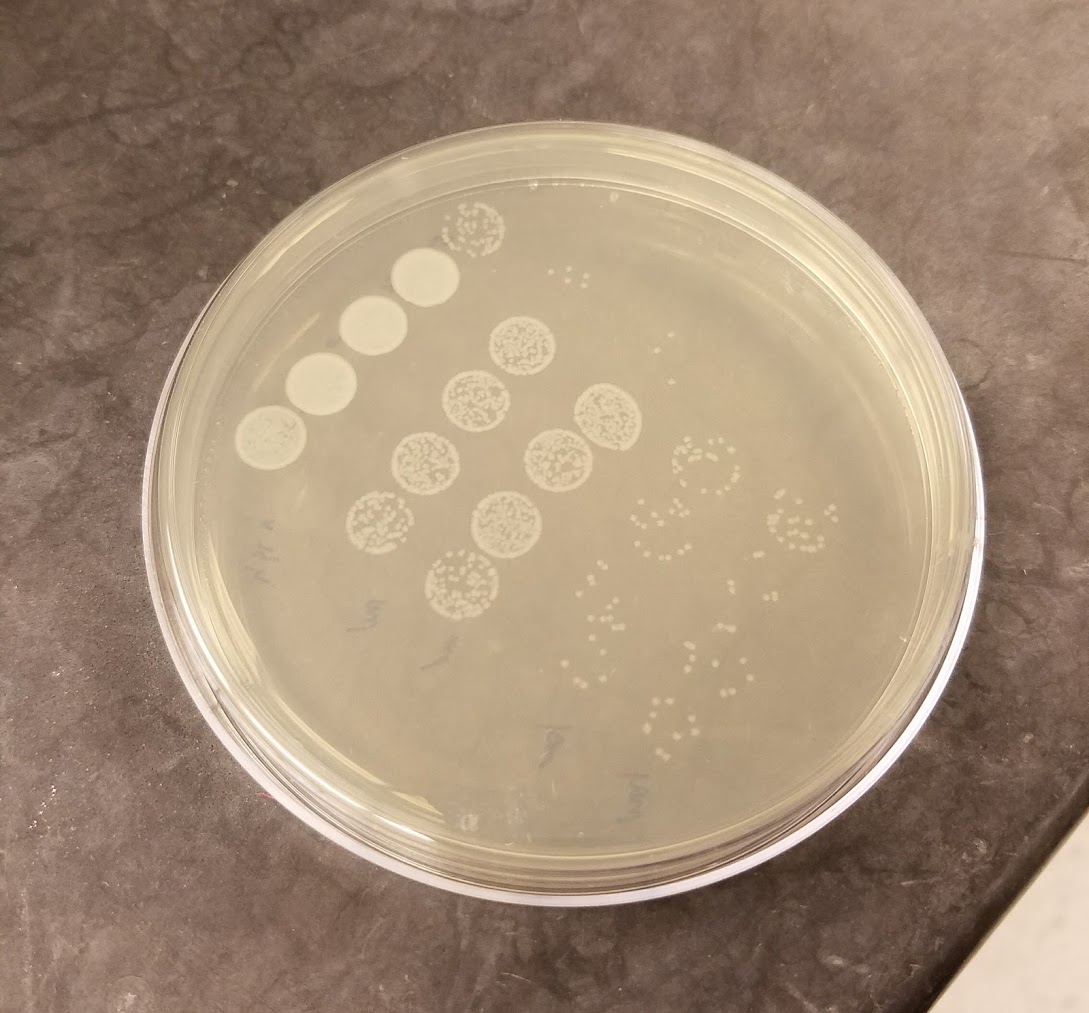

Bacillus thuringiensis colonies

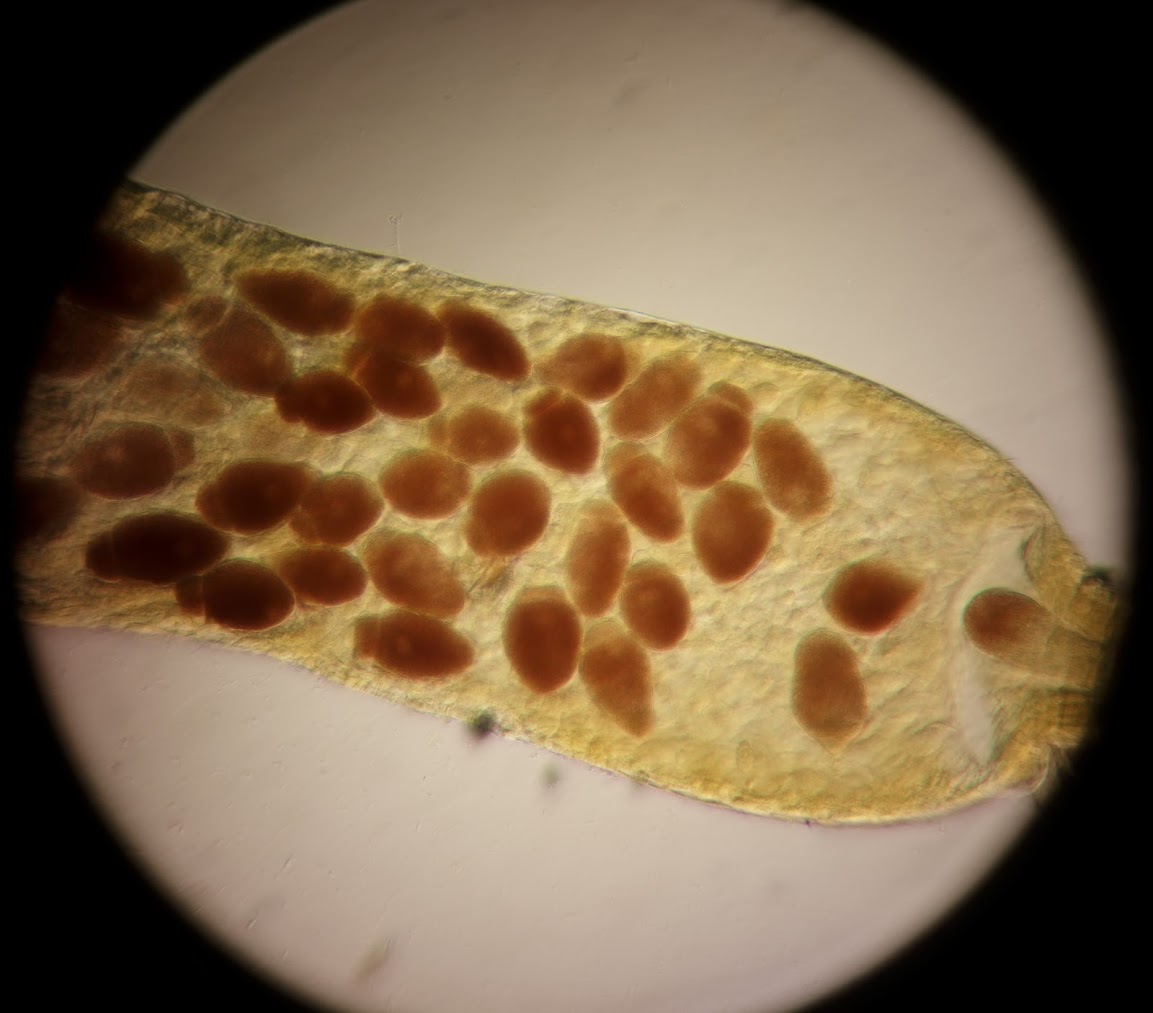

Eugregarine parasites in the beetle midgut

What we’ve discovered so far:

- Our theoretical models predict that the introduction of a second parasite can reverse the outcome of parasite-mediated competition among two host species in an assemblage if the second parasite alters mortality rates associated with the first (Rovenolt and Tate 2022).

- In flour beetles, coinfection with a gregarine parasite instigates the expression of a completely different set of immune genes after bacterial infection compared to beetles without gregarines, which is associated with an increase in the rate of bacteria-induced beetle mortality (Schulz et al. 2025). We are expanding these experiments to encompass several species that inspired our theoretical work – stay tuned for new results!

©2026 Vanderbilt University ·

Site Development: University Web Communications