Elms

Vanderbilt is well-known for its large and ancient oaks and magnolias. In this post, I would like to bring attention to another kind of tree that is significant in the arboretum: elms. Distinctive for their graceful, fan-shaped branches, they were once common but have now become relatively rare. Vanderbilt’s arboretum is home to a number of impressive survivors.

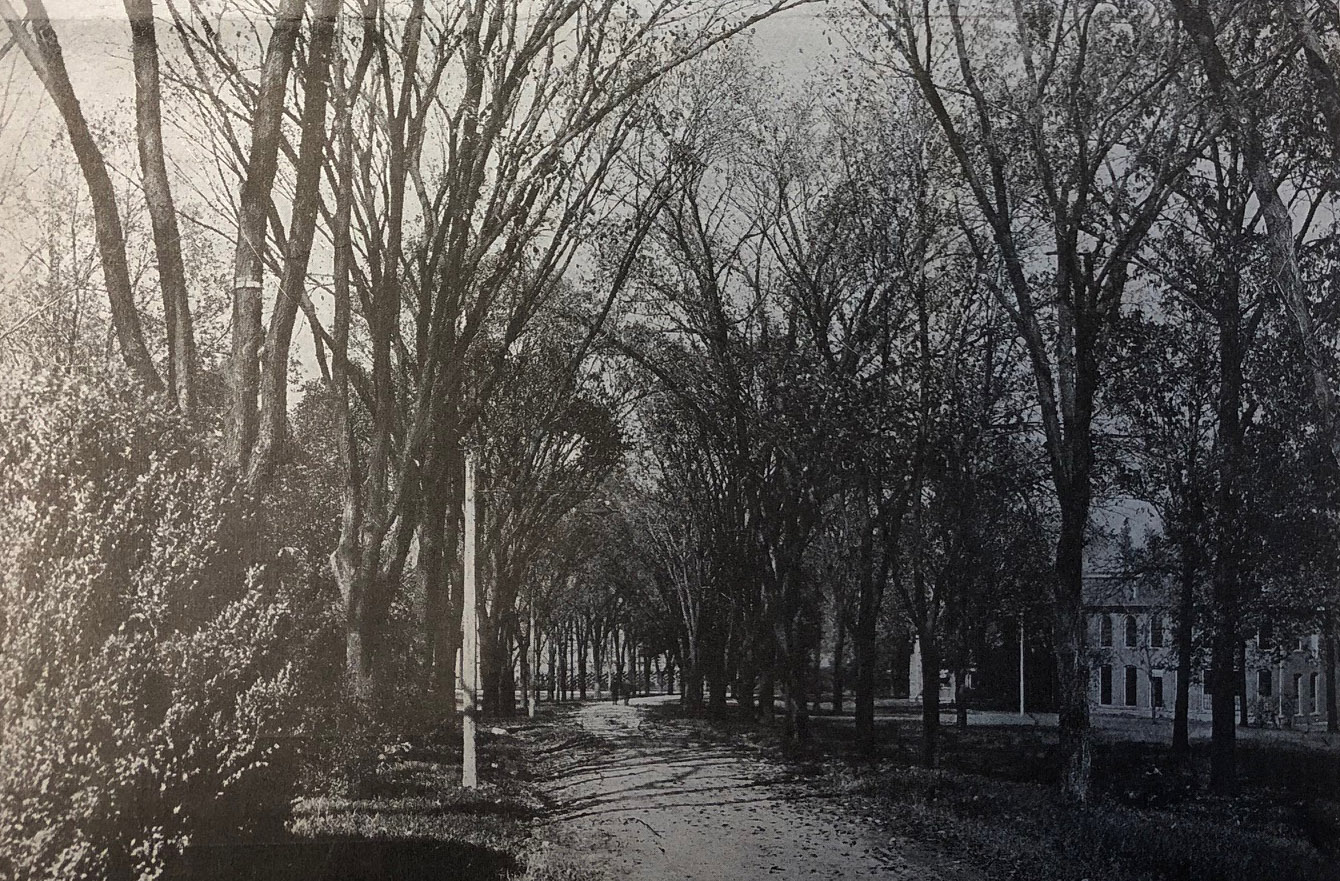

The outdoor cathedral

In the 1800’s native American elms (Ulmus americana) were widely planted along streets in cities all over the Unites States. They grew relatively quickly, were long-lived, and did well in urban conditions. When planted on both sides of a street, the soaring branches joined overhead to form a closed arch over the street. It is little wonder that nearly every town in the eastern U.S. has an “Elm Street”. The cathedral-like effect can be seen in the photo of Vanderbilt’s west campus in about 1920, taken from the article featured in my previous post.

Unfortunately, in the early 1900’s, a fungal disease, known as “Dutch elm disease” invaded the United States. Carried by bark beetles, the disease spread throughout the eastern U.S. and by the 1970’s had wiped out the majority of the mature elms. The practice of planting a monoculture of elms along streets did not help, as the disease could quickly spread from tree to tree.

Although there are insecticide treatments available for the disease, one of the best ways to prevent trees from becoming infected is to meticulously remove dead branches from the tree. Because of the care given to Vanderbilt’s trees, there are a number of noteworthy survivors on campus.

The Beta Theta Pi giant

Vanderbilt’s largest American elm, and probably the one in the best condition is in front of the Beta Theta Pi house on 24th Ave.S., just north of its intersection with Vanderbilt Place. With a height of 31 meters (100 feet), crown spread of 30 meters, and a diameter of 125 cm (49 inches), it’s the fifth largest tree in the arboretum and is one of the stars of the Tour of Giants tree tour. If you’ve never walked by it, you should definitely check it out – it’s spectacular! It still has most of its main branches, so you can get a feel for how impressive it would have been when both sides of a street were lined with trees like it.

The “West Avenue” elms

The “West Avenue” sidewalk as it appeared in 2014. One of the existing large American elms along its edge near Nealy Auditorium is pictured here. (http://bioimages.vanderbilt.edu/baskauf/90975)

West Avenue a little over 100 years earlier at nearly the same location, with the famous Garland oak in the center and the original Kissam Hall (now the location of Alumni Lawn) in the rear at the left. (Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University Archives photo PA.CAF.SCEN.007).

When the Vanderbilt campus was originally laid out, a dirt road known as “West Avenue” led from West End Avenue to a row of houses built as homes for faculty. Like most of the other streets on campus, trees were planted along its edge. I don’t think that those trees were exclusively elms, but certainly elms were included. When the roads leading to the interior of campus were removed in the 1950’s, many of them were replaced by sidewalks. Thus the major sidewalk from Rand Terrace to West End along Alumni Lawn follows the path of the old West Avenue.

There are four big American elms by the sidewalk in the vicinity of Rand Terrace. Two of them are on the Alumni Lawn side, seen in the picture above.

The other two are on the side opposite Alumni Lawn. The one directly across from Rand Terrace is at the right in the photo above (with the previously mentioned two in the distance). The other one is pictured at the beginning of this section.

These four trees aren’t quite enough for you to get the “cathedral” arch effect, but you can get a pretty good idea for the variety that exists in the typical shape of American elms.

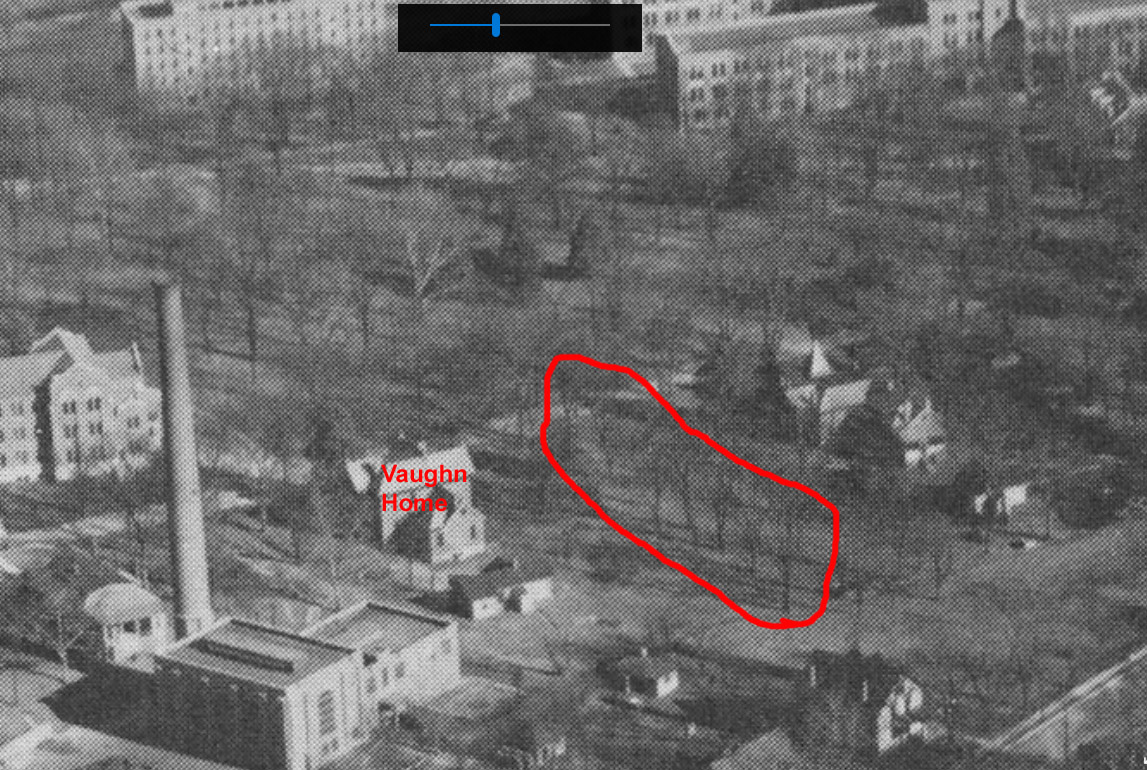

The Vaughn Home elms

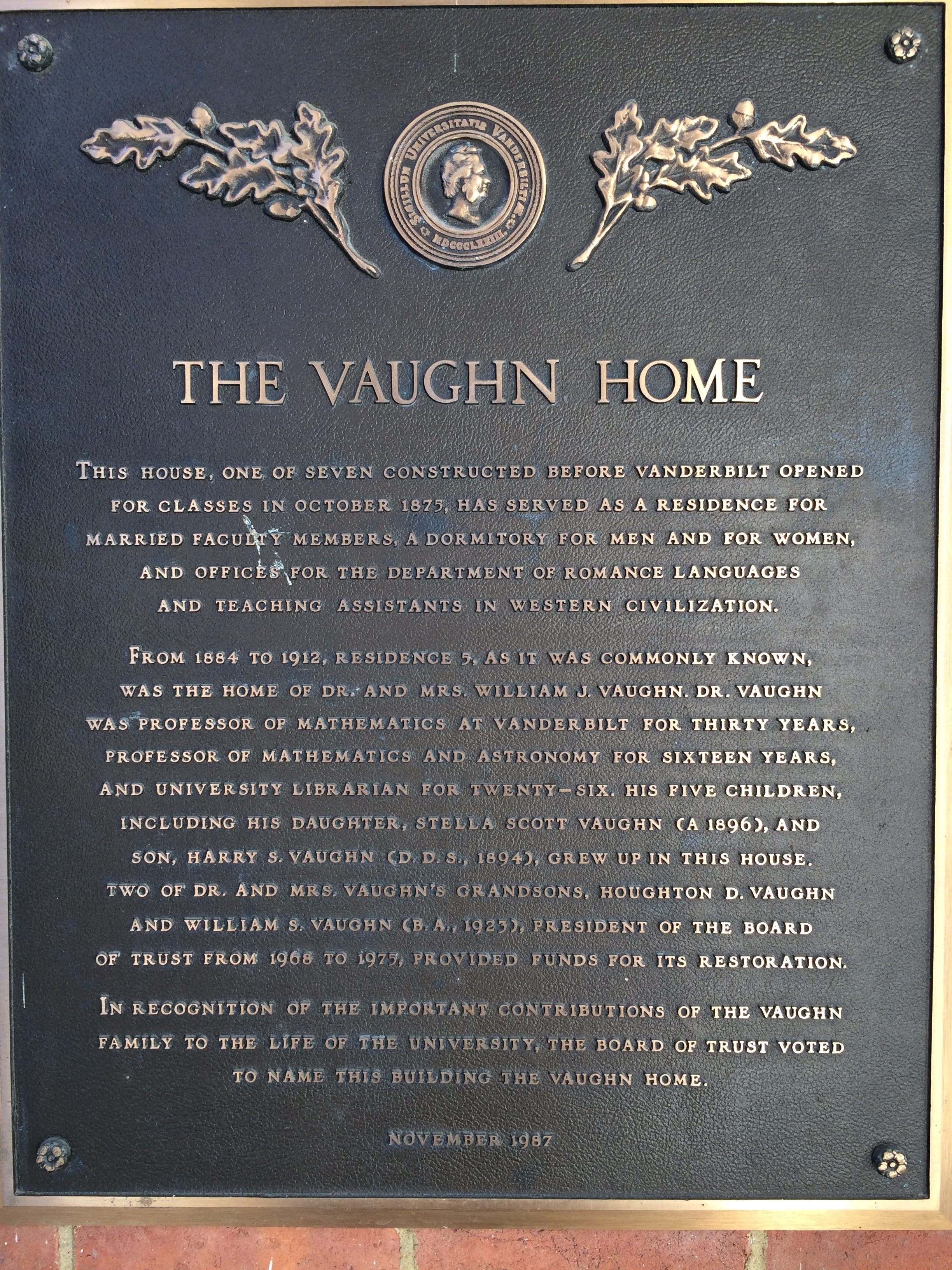

Five old elms growing near the Vaughn Home (old brick building visible in the center). If you aren’t familiar with the history of this building, read the plaque by its front door (image at the end of this post).

For years I’d noticed the five big American elm trees that grew in a row along the road that leads from Buttrick Hall past Jacobs Hall and to the Bryan Building. Although they still have the characteristic branching pattern of American elms, time has taken its toll on several of the trees that have lost a lot of their major branches. I’ve wondered if they had been planted along one of the original roads on campus, but it wasn’t until I happened to look at one of the old aerial photos of campus that I was inspired to dig into their history a little more.

I had a photo that I scanned from one of the Vanderbilt history books. Unfortunately, I didn’t record whether it was Conkin (1985)1 or McGaw (1978)2. I’m sure that the photo originally came from the archives, but they haven’t been able to locate it for me. In any case, while looking at the photo in the vicinity of the Vaughn Home (one of the original 6 faculty homes), I noticed some trees that might have included these five elms. I’ve circled the relevant trees in the photo below. By now, you’ve seen enough American elm photos to recognize the tell-tale shape of elms in the row of trees in the photo.

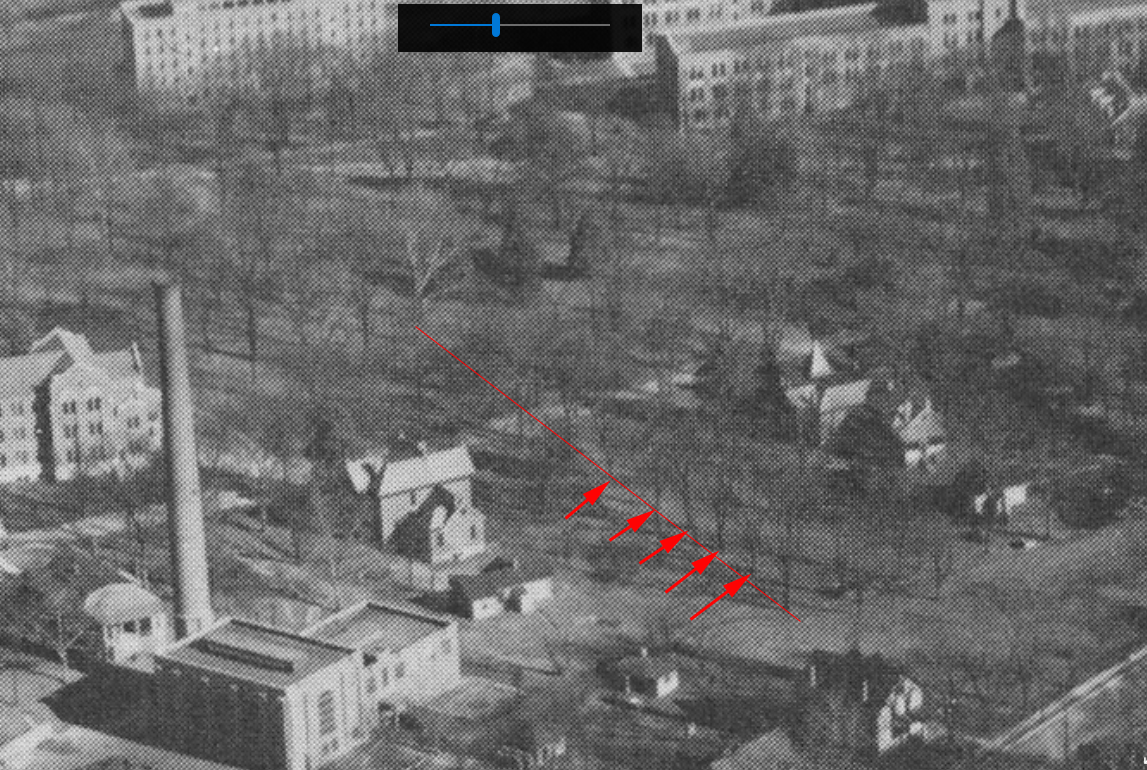

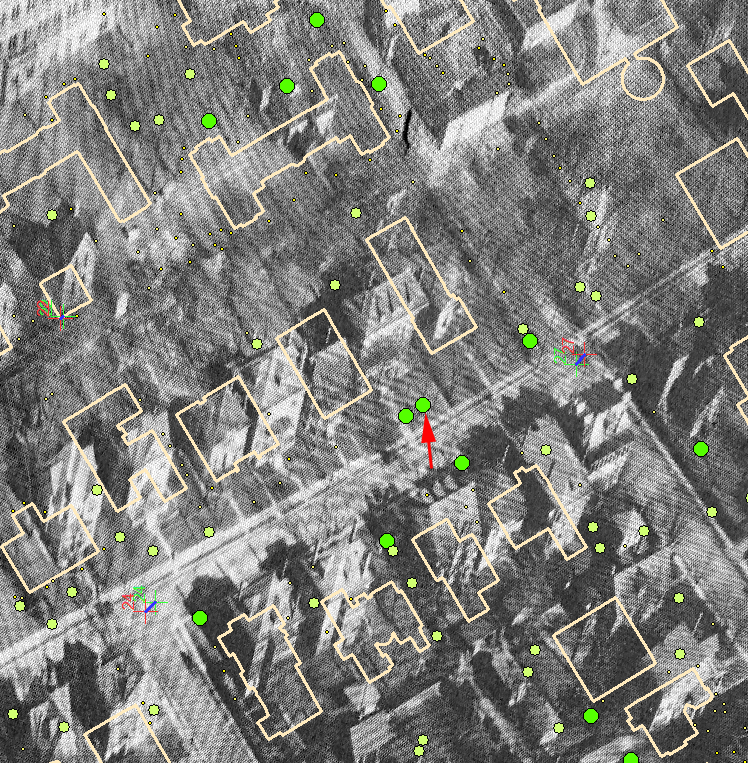

If you’ve read many of my earlier historical blog posts, or viewed the “How old are the trees” page on the arboretum website, you’ll know that I really geek out on analyzing old aerial photos to try to find existing trees when they were much younger. In this case, I decided to georectify this photo using ArcMap GIS to see if the positions of any of the trees in that row matched the current positions of the five elms near the Vaughn Home.

The georectification process involves matching “control points” on the photo with known positions on the GIS layer (in this case the footprints of existing buildings). Because Buttrick Hall, the Vaughn Home, and the Community Partnership House (plus two street intersections) all existed on the old photo and on the present day building layer, the software did a pretty good job of stretching out the photo to overlay it on the map. The locations of the 5 elm trees on the map are shown with arrows. The line made by the bases of the 5 elm trees was extended to show that it nearly coincides with the giant sycamore tree that is still present in the upper Stevenson courtyard. Because it’s white bark is so apparent, that sycamore is easily recognized in wintertime aerial photos of Vanderbilt.

If you look carefully, you can see that the bases of the trees of the trees I circled fall on the red line in the georectified photo, and are at about the same spacing as in the tree layer dots. So although it’s difficult to match particular trees on the photo with particular present-day trees, I’m pretty confident that the five existing elms are the same trees as the row in the photo. Here’s the photo again with arrows showing my best guess of which trees are the five existing ones. I also included the red line that leads to the base of the white-barked sycamore tree.

Because the photo included Wesley Hall (which burned in 1932) and Buttrick Hall (build in 1928), the photo can be dated to about 1930. That means that those five elms were large trees 90 years ago. Being a data nerd, of course I wanted to know just how tall they were. I made an expedition to the Vaughn Home and using a little geometry and a tape measure, I estimated that the height to the ridge of the building was about 11.5 m. In the photo, that distance was about 82 pixels. I estimated the heights of the trees pointed to by the red arrows as ranging between about 75 to 85 pixels. That put the heights in 1930 of the five elm trees at between about 10.5 to 12 meters (about 35-40 feet). A bit of web searching told me that healthy elms could grow to this height in around ten years. So that is an indication that these five elms by the Vaughn Home are probably at least 100 years old.

While I was measuring, I decided to measure the current (2018) heights and diameters of the five elms. In order, from the Bryan Building to Jacobs Hall, the diameters were: 85 cm, 94 cm, 78 cm, 64 cm, and 94 cm. The respective height estimates were: 19.2 m, 22.5 m, 22.9 m, 19.7 m, and 21.5 m. My Internet source said that elms could reach a diameter of a meter in 100 years, so that would be consistent with my earlier age estimate.

Because these trees were clearly planted in a line, at first I thought they were planted along the edge of a road that no longer exists. However, there is no sign of that road on the 1930 picture and there isn’t any formal road at that location in any of the campus maps from 1875 to 1900 that I’ve seen. It may have been that there was an unofficial lane that was framed by the trees. Although it’s hard to tell from the picture, it looks like perhaps there were several rows of elms planted in that area.

The success of this approach in locating and determining the 1930 heights of the Vaughn Home elms led me to take a similar look for the Beta Theta Pi giant on the same photo. Here’s that portion of the campus in georectified form:

The location of the Beta Theta Pi elm is indicated with the red arrow. Here’s what the original, un-rectified photo looks like, with an arrow at the same position as above:

It’s apparent from this photo that in 1930, 24th Ave.S. was lined with a row of American elm trees. There are three very big ones between the arrow and the corner of Vanderbilt Place, with more big ones continuing south past Vanderbilt Place. The arrow points at one of the smaller trees north of the three big elms.

Because none of the buildings in this part of the photo still exist, I couldn’t perform the same scaling exercise as I did using the Vaughn home. However, I was able to get an estimate of the pixel size by measuring the pixel distance between the intersection of 24th Ave.S. with Kensington Place and Vanderbilt Place (522 pixels). The GIS map told me that distance was 133 m. I estimated that the three tall elms were about 60 pixels tall and the smaller trees to the left were about 40 pixels tall. That would make their heights 15 m and 10 m (50 ft. and 33 ft.), respectively. Based on this estimate, in 1930 the smaller trees to the left were similar in size to the Vaughn Home elms.

At 31 meters, the Beta Theta Pi giant is currently 50% taller than the Vaughn Home elms, and its current 125 cm diameter is about 50% wider than the Vaughn Home elms are now. So although my georectification puts the red arrow on one of the smaller trees, based on how much larger the Beta Theta Pi tree is than the Vaughn elms, I think it is more likely that the leftmost big elm in the 1930 photo is actually the Beta Theta Pi tree. It’s possible that either the GPS location measured for the existing tree in the GIS database is off, the georectification is off, or both.

I tried to take a photo of the tree from a similar angle as the aerial photo to see if the branching pattern corresponds to the appearance of the larger elm in the aerial photo.

There are some similarities in the branch shape, but I’m not convinced. You’ll have to judge for yourself whether it’s similar enough to match the big elm in the 1930 photo.

So how old is the Beta Theta Pi elm likely to be? Height alone probably isn’t the best indication. Based on what I’ve read online, it appears that once elms mature, a lot of their growth may go into increasing their crown spread and trunk diameter rather than their height. For example, the national champion elm is 34 meters tall with a diameter of 262 cm, while another large elm was 29 meters tall with a diameter of 250 cm. So although these champion elms have double the trunk diameter of the Beta Theta Pi tree, they are about the same height. One source said that mature elm trees add about 1.25 cm to their trunk diameter per year. At that rate, the additional 40 cm of diameter that the Beta Theta Pi tree has over the Vaughn Home elms could represent an additional 30 years of age. That would put its age at around 130 years old or older. Because the large elm trees on the photo were clearly lining the side of 24th Ave.S., they were probably planted around the time the street and adjacent lots were platted. I haven’t dug into any historical records to try to find out when that occurred.

Since it is growing at a location outside of what was university property prior to 1900, it’s not likely to have been established as part of Bishop McTyeire’s massive tree-planting efforts. But it’s still awesome and one of the arboretum’s most amazing trees !

American elms vs. September elms

One of the unique features of the Nashville area is that it is the center of the universe for another species of elm that is not commonly found outside of Tennessee: September elm (Ulmus serotina). As far as I know, September elms are indistinguishable from American elms other than by the time of year when they bloom and set fruit. As the name suggests, September elms bloom in the fall, from about the second week of September through the first week of October. In contrast, American elms are one of the earliest blooming trees in the spring, from about the fourth week of February through the second week of March in Tennessee.

Lest you get too excited about running out and looking for exciting flowers on these elms, be aware that like many other wind-pollinated trees, the flowers of all elm species are tiny and mostly green. After pollination, the seeds develop into tiny, flattened single-seeded fruits with a circular, papery wing that surrounds the center. By this time of year (the first week of April), American elm fruits have completed their development and have fallen from the trees. You may notice great piles of these fruits accumulating against curbs or stair steps where they’ve blown up against an obstruction.

So if you are a bit patient, it’s actually pretty easy to determine if a particular tree is an American elm or a September elm – just check under it in April and November. If you see fruits on the ground in April, it’s an American elm. If you see fruits under it in November, it’s a September elm.

September elms in the arboretum

September elm is also susceptible to Dutch elm disease, so it is noteworthy that Vanderbilt has some really nice specimens of September elm.

Through the 1990’s Vanderbilt actually had the national champion September elm tree. It stood near the corner of Benson Science Hall. However, it came down by 2005 – I’m not sure what caused its death. Fortunately, there are still several other September elms that survive near Benson.

Between Benson/Old Central and Rand, there are two relatively large September elms. I’m not sure of their history. They are not apparent in the older aerial photos and don’t seem to line up with any old roadway. They may have just been stuck in at that location as part of a general landscaping plan.

The largest September elm

One of my favorite trees at Vanderbilt is the largest September elm in the arboretum. Although it doesn’t have a particularly large crown spread, it soars to a height of almost 100 feet (29 meters). That makes it taller than the national champion tree, which grows near the entrance to the Warner Parks Nature Center in Nashville. The national champion’s diameter of 109 cm is quite a bit larger than our tree’s 83 cm – our tree probably isn’t nearly as old. However, the champion tree has not been maintained well and if it were to succumb to Dutch elm disease due the the large amount of dead wood in its branches, the Vanderbilt tree would probably take its place as champion. Don’t get me wrong – I’m not wishing ill on the Warner Parks tree. But is is cool to think that because of the restricted range of September elm, the arboretum probably has one of the largest September elm trees in the world!

As spring progresses, I encourage you to take a few minutes to walk around campus and appreciate some of the amazing and ancient elm trees that we are lucky enough to have in the arboretum.

Steve Baskauf is a principal senior lecturer in the Biological Sciences Department at Vanderbilt University. He serves as the communications coordinator for the Vanderbilt Arboretum and can be contacted at steve.baskauf@vanderbilt.edu. Posted 2018 April 7. Unless otherwise noted, the images on this page were photographed by him.

References

1 Conkin, Paul K. 1985. Gone with the Ivy: A Biography of Vanderbilt University, University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

2 McGaw, Robert A. 1978. The Vanderbilt Campus: A Pictoral History, Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville.

Here’s the Vaughn Home plaque: