Author Conversations: Mastodons to Mississippians

The 33rd annual Southern Festival of Books is this weekend, and Vanderbilt UP is celebrating our recent regional history books during the lead-up to the festival. One of those recent books is Mastodons to Mississippians: Adventures in Nashville’s Deep Past, written by archaeologist Aaron Deter-Wolf and anthropologist Tanya M. Peres.

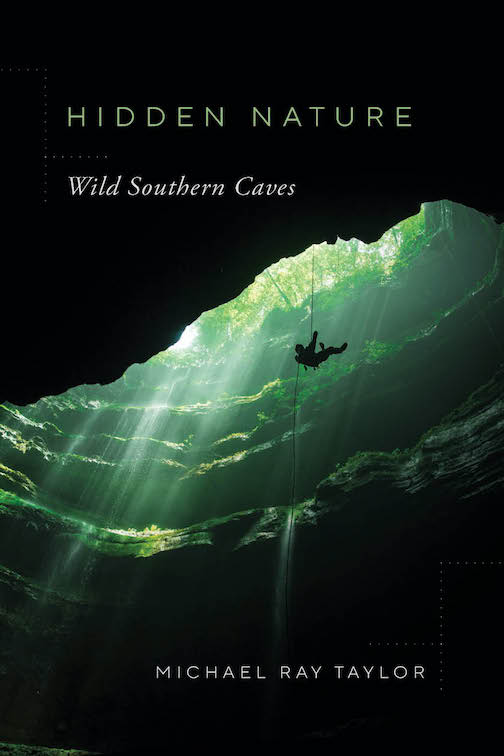

This past week, another Vanderbilt UP author, Michael Ray Taylor—whose book Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves (2020) was recently named a finalist for the 2021 Reed Environmental Writing Award by the Southern Environmental Law Center—spoke with Deter-Wolf and Peres about their work and about writing Mastodons to Mississippians. Keep reading below for their interesting discussion.

About Mastodons to Mississippians: Some history texts written for schoolchildren and the public have led us to believe that the first Euro-Americans arrived in Nashville to find a pristine landscape inhabited only by the buffalo and boundless nature, entirely untouched by human hands. However, during the period between about AD 1000 and 1425, a thriving Native American culture known to archaeologists as the Middle Cumberland Mississippian built the first urban landscape in what would become Nashville. Theirs is one of the stories of the city’s deep past, a history that includes mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and millennia of Native American settlement along the Cumberland River.

Aaron Deter-Wolf and Tanya M. Peres: Fantastical pseudo-archaeological stories of things like lost giants and ancient aliens used to be spread mainly in print, but today we contend with the 24/7 accessibility of the internet, social media, and on-demand “edutainment” programs. We both receive calls and emails every month from members of the public who are fascinated by archaeology and have some pretty creative visions of the past. Over the years these have included limestone slabs carved with secret microscopic images that can only be revealed under green light, a hidden race of Sasquatch-human hybrids building stone piles in the woods, and a parade of dinosaur eggs and “penis stones.” Those stories aside, it’s great that people are interested in the deep past, and we hope we’re able to help them understand it better!

The infamous “Grand Monster,” the First American Bank Smilodon, and other archaeological treasures you describe were first discovered when contemporary excavations intersected hidden limestone caves. How does Nashville’s limestone foundation contribute to preservation of its past?

Many archaeological sites have been destroyed by modern construction, and you mention the likely loss of currently unknown sites in the River North and East Bank development areas. What can be done to increase proper excavation and protection of sites like these in a rapidly growing city?

Unfortunately, most archaeological sites in Tennessee aren’t protected under state or local laws unless a development is subject to environmental or cultural resource permitting. This means that while individual graves of any age are protected by state cemetery statutes, developers are not required to look for, or avoid, any other part of an archaeological site. There are some cities that go further and include archaeology in their regulatory or permitting processes. For example, St. Augustine, Florida, has an archaeological preservation ordinance, a city archaeologist, and an active public archaeology network, all of which work to balance development and archaeological needs. It’s also critical for businesses and developers to partner with archaeologists and take a proactive approach toward heritage preservation and archaeological stewardship.

Aaron Deter-Wolf is a prehistoric archaeologist for the Tennessee Division of Archaeology. Tanya M. Peres is an associate professor of anthropology at Florida State University.

Aaron Deter-Wolf is a prehistoric archaeologist for the Tennessee Division of Archaeology. Tanya M. Peres is an associate professor of anthropology at Florida State University.

Michael Ray Taylor is a professor of communication and the chair of the Communication and Theatre Department at Henderson State University in Arkansas. He is the author of several books, including Hidden Nature, Cave Passages, Dark Life, and Caves, as well as articles in Sports Illustrated, the New York Times, Houston Chronicle, Wired, Audubon, Reader’s Digest, Outside, and many other print and digital publications.

Leave a Response