Recapping 3 Notable Federal Developments Affecting Marijuana Law in 2018

The title of this post was the focus of my remarks on a panel at the 2018 National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) annual summit in Los Angeles, held at the end of July. The panel drew a packed room, attesting to state lawmakers’ interest in marijuana law and policy.

You can watch the full panel (including yours truly, Representative Eric Hutchings of Utah, Senator Roger Katz of Maine, and Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer of California) on the NCSL Facebook page here (it’s about 1 hour long). Below, I’ve summarized my own remarks regarding federal developments; I’ve also added links to prior posts that expand upon each of my points:

In 2018, there have been at least three important developments concerning marijuana law and policy at the federal level. Each of these developments could affect the ability of state lawmakers to regulate marijuana as they see fit.

The FIRST development occurred back in January, when United States Attorney General (AG) Jeff Sessions rescinded marijuana enforcement guidance that had been issued by the Obama Administration. This guidance, known as the Ogden and Cole memoranda, had suggested the Department of Justice (DOJ) wouldn’t prosecute anyone who was acting in compliance with state marijuana laws.

At the time, the AG’s announcement stoked fears that the DOJ was planning to crack down on the state-licensed marijuana industry. But those fears proved unfounded. My earlier post (see here) explains why in greater detail, but let me highlight 2 reasons the DOJ hasn’t attempted to crack down and likely won’t ever do so in the future:

- For one thing, congress has tied the DOJ’s hands, at least with respect to MEDICAL marijuana. In each budget it has adopted since 2014, Congress has prohibited the DOJ from spending any of its allotted funds to prosecute medical marijuana users and suppliers who obey state law. This means that even if AG Sessions wanted to crack down on the medical marijuana industry, he couldn’t do it – he lacks the power.

- A second reason the DOJ has held back is that the agency simply doesn’t have the spare resources it would need to mount an effective crackdown on today’s marijuana industry (medical or otherwise). In other words, even without enforcement guidance or spending restrictions in place, the DOJ probably couldn’t put this cat back in the bag, so to speak.

In sum, while the rescission of enforcement guidance didn’t make it any easier for state lawmakers to pursue marijuana reforms, it hasn’t necessarily made it any more difficult either.

The SECOND development came from the Supreme Court in a case seemingly having nothing to do with marijuana: Murphy v. NCAA. The case arose several years ago when the state of New Jersey tried to repeal an old state ban on sports gambling. Several sports leagues (including the NCAA) sued New Jersey under an obscure federal law known as PASPA (the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act). In relevant part, PASPA prohibited the states from “authoriz[ing]” or “licens[ing]” sports gambling. The sports leagues prevailed in the lower courts, which enjoined New Jersey’s repeal, a move which effectively forced the state to keep its (no longer wanted) ban on sports gambling.

New Jersey, however, convinced the Supreme Court to hold that PASPA was unconstitutional. In particular, the Court held that the statute violated the anti-commandeering rule. In so doing, the Court endorsed an interpretation of that rule that I’ve been espousing for nearly a decade—namely, that it empowers states to legalize an activity even when Congress forbids it. Although the Murphy case involved sports gambling, it logically applies to marijuana possession/manufacture/distribution and other activities as well.

Of course, the Murphy decision doesn’t empower states to do whatever they want regarding marijuana policy. Nonetheless, it should put an end to a variety of misguided lawsuits claiming that state marijuana reforms are preempted to the extent they authorize or license marijuana activities (like possession and distribution) that are forbidden by federal law. For more of my thoughts on the Murphy decision and its implications for state marijuana reforms, you can visit this post here.

The THIRD noteworthy development came from Congress in the spring. Prompted at least in part by the AG’s rescission of enforcement guidance, Senators Cory Gardner and Elizabeth Warren introduced bipartisan legislation that would dramatically change federal law governing marijuana.

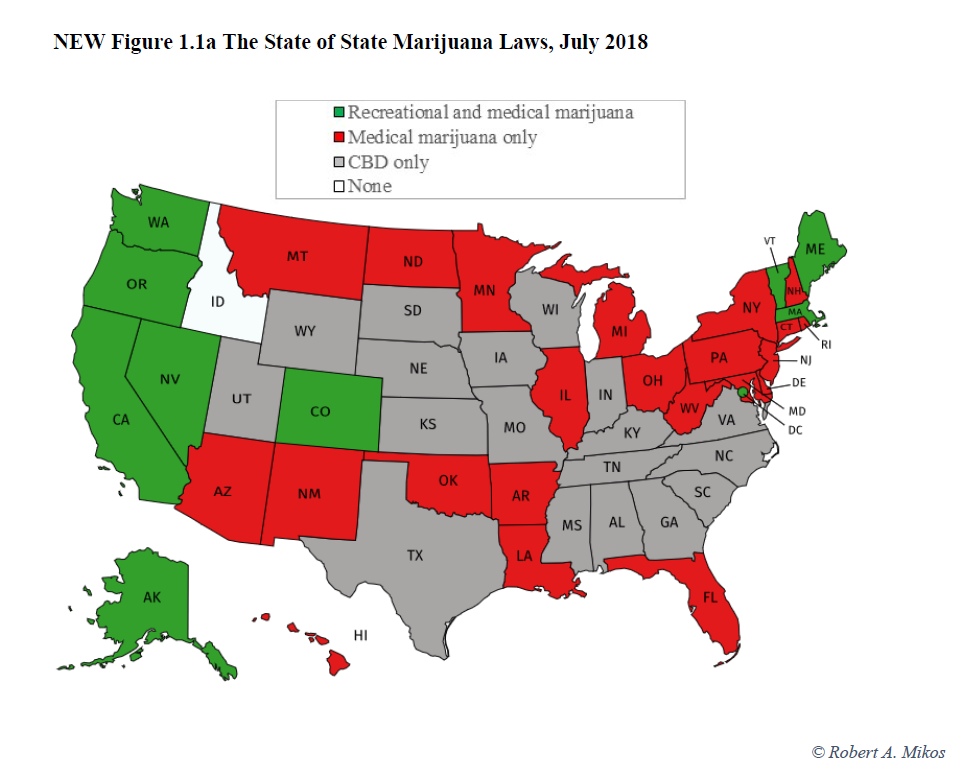

The proposal is called the STATES ACT, and you can read more about it in this post here. To simplify somewhat, the STATES ACT would turn federal supremacy on its head—it would empower state lawmakers to legalize the possession, manufacture and distribution of medical marijuana UNDER FEDERAL (and not just state) law. So federal law would take on some of the contours and hues of state law, as depicted on this map:

If it passed (and that’s a big IF), the STATES ACT would fundamentally alter the balance of power over marijuana law and policy. Under the Act, states could remove all of the obstacles that medical marijuana users and suppliers now face because of the federal ban on marijuana. For example, marijuana suppliers would be able to obtain federal trademark and bankruptcy protection as well as financial services from federally regulated banks.

Of course, Congress may not pass the STATES ACT (or something like it), at least anytime soon. Nonetheless, I want to call your attention to a little known fact: Congress has already given state lawmakers the power to turn off the federal marijuana ban in some limited circumstances. Let me give you one quick example as I wrap up.

The example involves marijuana paraphernalia—the equipment people use to consume and produce marijuana (think of vape pens and grow lights). Right now, the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) bans this equipment, no less than it bans marijuana. The ban is found in 21 U.S.C. Section 863(a) and is discussed in my book on pages 410-411. However, when Congress added this ban to the CSA in the 1980s, it also added an obscure (and hence seldom utilized) provision that enables states to turn off the federal ban by specifically authorizing the possession, manufacture, and/or distribution of drug paraphernalia under state law. This provision is found in 21 U.S.C. Section 863(f) and is discussed in my book on pages 410-411. Under Section 863(f), if a state passed a law specifically authorizing the possession, manufacture, and / or sale of drug paraphernalia under state law, it would seemingly make these devices legal under FEDERAL law as well.

To be sure, provisions like Section 863(f) are limited in scope. Nonetheless, they provide an example of what states could do to ameliorate the conflicts with federal marijuana law while waiting upon Congress to take up broader reforms.