Why I Went to Prison

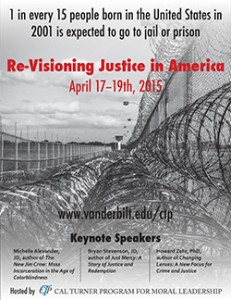

This post is written by Eric Brown, an alumnus of Vanderbilt Divinity School who works with the Nashville office of The Children’s Defense Fund where he addresses the challenge of the Cradle to Prison Pipeline and serves as an active member of the Re-Visioning Justice Working Group facilitated by the Cal Turner Program for Moral Leadership in the Professions. This group convenes local academicians and activists to consider the problems that attend mass incarceration and the death penalty and to develop ways to address them. Eric will be speaking on the Cradle to Prison Pipeline at the “Re-Visioning Justice in America” conference, April 17-19, 2015.

This post is written by Eric Brown, an alumnus of Vanderbilt Divinity School who works with the Nashville office of The Children’s Defense Fund where he addresses the challenge of the Cradle to Prison Pipeline and serves as an active member of the Re-Visioning Justice Working Group facilitated by the Cal Turner Program for Moral Leadership in the Professions. This group convenes local academicians and activists to consider the problems that attend mass incarceration and the death penalty and to develop ways to address them. Eric will be speaking on the Cradle to Prison Pipeline at the “Re-Visioning Justice in America” conference, April 17-19, 2015.

Why I Went to Prison

I was a good kid. I did not have any priors, yet still ended up in Riverbend Maximum Security Prison. I did not want to be there, but I did my time. I watched the clock’s tortoise-like speed, waiting for my freedom. Come 8PM, I was able to see freedom and opportunity again.

I’m different from the many who are incarcerated at Riverbend. I volunteer to go. It is mandatory for the guys on the inside to do an extended amount of time to pay a debt to society. I did not go to prison because of a crime, but because of this nagging white lady named Janet Wolf.

Where Janet saw a sickening atrocity of black, brown, and poor bodies placed in cages and stripped of their humanity, I saw thugs and criminals doing time they deserved for their crimes. I never talked about this feeling much because somewhere deep inside, I knew I sidestepped being in one of these cages myself. I am conditioned to think that prison is only for those who do bad things, and not for those who really may need a special needs facility instead. I thought prison was for bad people not realizing that courts too often lock up a person who looked the part, but never played the part. I never took into consideration people doing life sentences for non-violent crimes involving twenty dollars worth of a drug. Most importantly, I did not realize the reason I did not want to be in prison is because most of the people looked like myself; young, male and black.

Too often, being in prison is synonymous with being black. No one saw the intellect of these guys on the inside. They saw only convicts. People did not see the behind the scenes stories of drug abuse, violence, or innocence. They saw only “guilty as charged.” At Riverbend, no one saw men made in the image of God. They saw delinquents who must constantly pay for their crimes, even after their release. Not enough people asked, was there a support base or a listening ear hearing a cry of plea before ending up in this place? Not enough people understand the impact on the families of the incarcerated, who already live paycheck to paycheck and now pay more to stay in contact with their imprisoned loved one?

Many do not know because this topic is hidden from the consciousness of people living in the busy-ness of their lives. What does this have to do with me? Being pressured to come to prison forced me to deal with the reality of knowing that people of my faith know little about our faith. If I am called as a Christian to go to those who are held captives, either I am not a good Christian, or I am a very good oppressor in my complacency. Being forced to go to prison caused me to ask this question at my church, “Who in this service knows someone in prison?” When I saw around 80 to 90 percent of the membership raise their hands, I knew they were lying to other people saying their family member went to college, I saw the shame that is assumed by the black race. God is calling us to see that this injustice in our society is lucrative for some, while being a financial, spiritual, and mental burden for others. But are we listening?

I went to prison, not as one who is bodily incarcerated, but as one mentally caged from seeing complexities. Now, however, I go to prison as a student learning how prison is a microcosm of the outside world. My fear is that my organization’s work for children’s rights means nothing when the prison business is booming with a fresh crop of young black and Latino males ripe for the picking. I continue to go to prison, to keep younger ones from falling through the cracks and landing in brand new cages that strip humans to commoditized animals.

From Nashville, TN, Eric Brown is the Lead Organizer of the Children’s Defense Fund’s Nashville Team. He is also the assistant to the pastor of Jefferson Street Missionary Baptist Church. He was graduated from American Baptist College, and earned master’s degrees in theological studies and ethics from Vanderbilt University. Follow Eric on Twitter @ConsiderEso

March 18th, 2015

“Cradle to Prison Pipeline” – never heard that one. But it seems only too true. Now, if we think of such things as “no child left behind” and/or “affirmative action” and if these were of any use, then prison population in the US, let alone the “white to black ratio” should decline, shouldn’t it? How then can the opposite be true?