Aphids and Digital Archives: Thinking Through Digital Preservation with Dionne Brand’s The Blue Clerk

“In the mornings the clerk reads the obituaries. All of these bales may be considered obituaries of a sort but we are talking about the regular obituaries where people actually die. Here on the dock nothing and no one dies. The clerk would like them to die the finite closed death of a real obituary of the type as the ones in newspapers. Aphids do not kill leaves, per se. They extrude the sap of them and they expel a sweet substance of their own called honeydew, etc., etc., on down the line.” “Verso 25” Dionne Brand, The Blue Clerk: Ars Poetica in 59 Versos

By Nathan H. Dize

As an avid reader of Dionne Brand’s poetry, I knew that as soon as her new collection The Blue Clerk came out that I had to have it. Her collections Ossuaries and Inventory have helped me in the past when articulating my thoughts about the creation of archives and understanding the reverence that Caribbean communities have for the dead. The Blue Clerk is also concerned with similar themes as it focuses on the conversation between a shipping clerk and a poet standing on a wharf. Their conversation, and arguments, center around what the poet has withheld, left unwritten. As the keeper of the poet’s papers, the Blue Clerk is cast as the archivist.

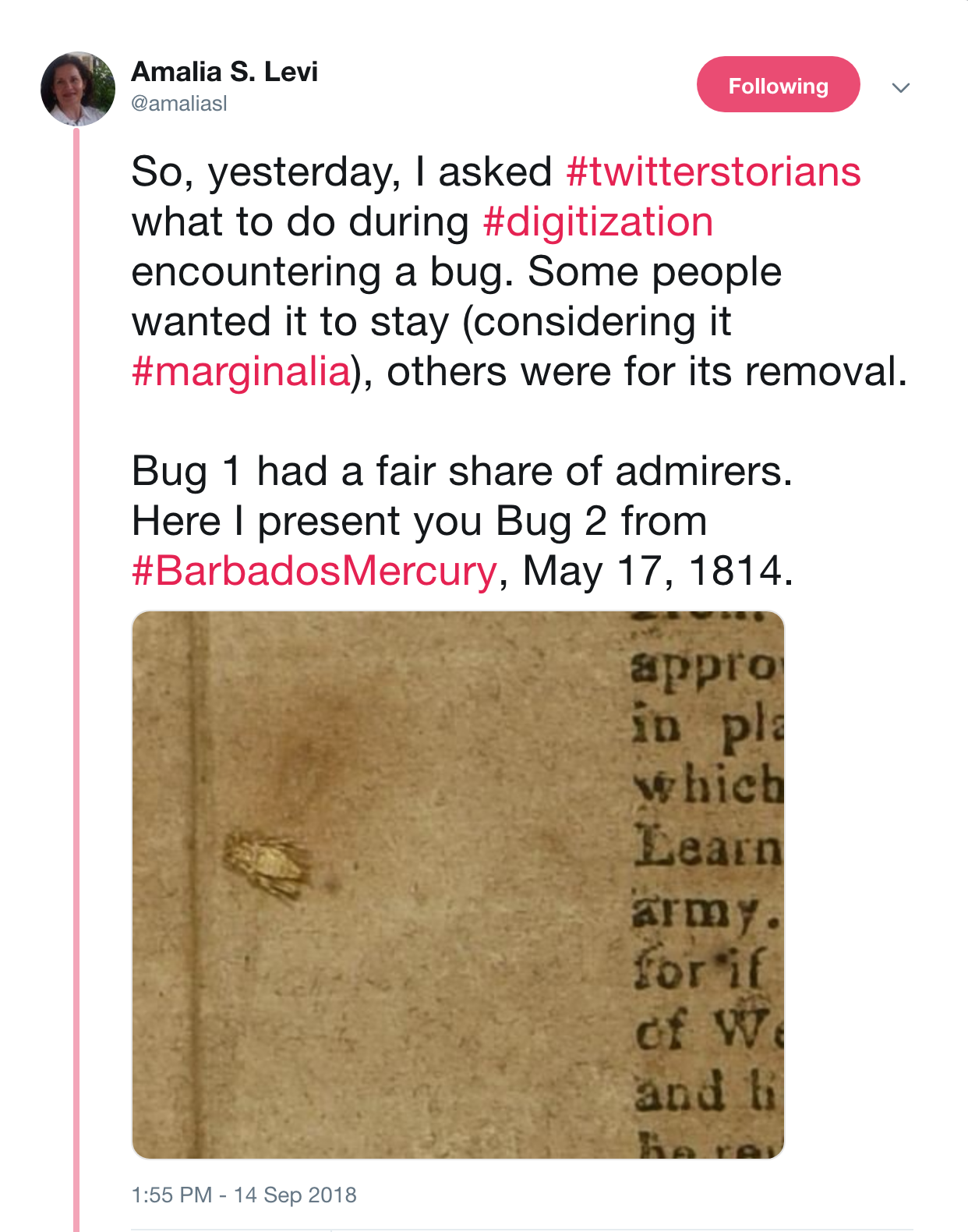

One of the recurring images throughout the collection is the idea of environmental decay, causing the poet’s papers to weather over time. The aphids burrow, eat away, and transform the bales of documents over time, creating new layers of meaning and sensation. While reading The Blue Clerk, I could not stop thinking about a series of tweets by Amalia S. Levi on the bugs that she and the digitization team for the Barbados Mercury recently found while preparing documents to be scanned (see the image of one of the tweets below). If you haven’t been following the digitization efforts you should! It is almost as Brand writes in “Verso 41.1,” “[the] aphids dove in the shape of anchors. I smelled twelve thousand desert flowers. We were joined by one million bees, they slept in the folds of our documents…” (Brand 204).

In her tweets, Levi mentions that among the project team members there was some dispute as to what to do with the bugs that had dug into the folds of the newspaper. For archivists and enthusiasts, and even Brand, the bugs represent another layer of meaning. The bugs reconnect the subjects and the worlds within the bales of documents to the real world. In a sense, the bugs are the first to re-animate the unprocessed archive. For the aphids and other bugs, the byproducts of their endeavors are the stuffs of an archivist’s nightmare. They are taking organic matter, ink and paper, and attempting to process it for other, more organic ends.

Brand, and any archivist for that matter, provides ample space for reflection on the precarity of archival material. This is something that has been on my mind quite a lot recently as I have been conducting research in the Special Collections at Fisk University, where whenever I leave my table, flecks of acidic print paper roll down my shirt. Something Brand’s clerk refers to at one time as “a sand of indecipherable-ness” (Brand 210). The Barbados Mercury team has also had to manage decaying paper as well.

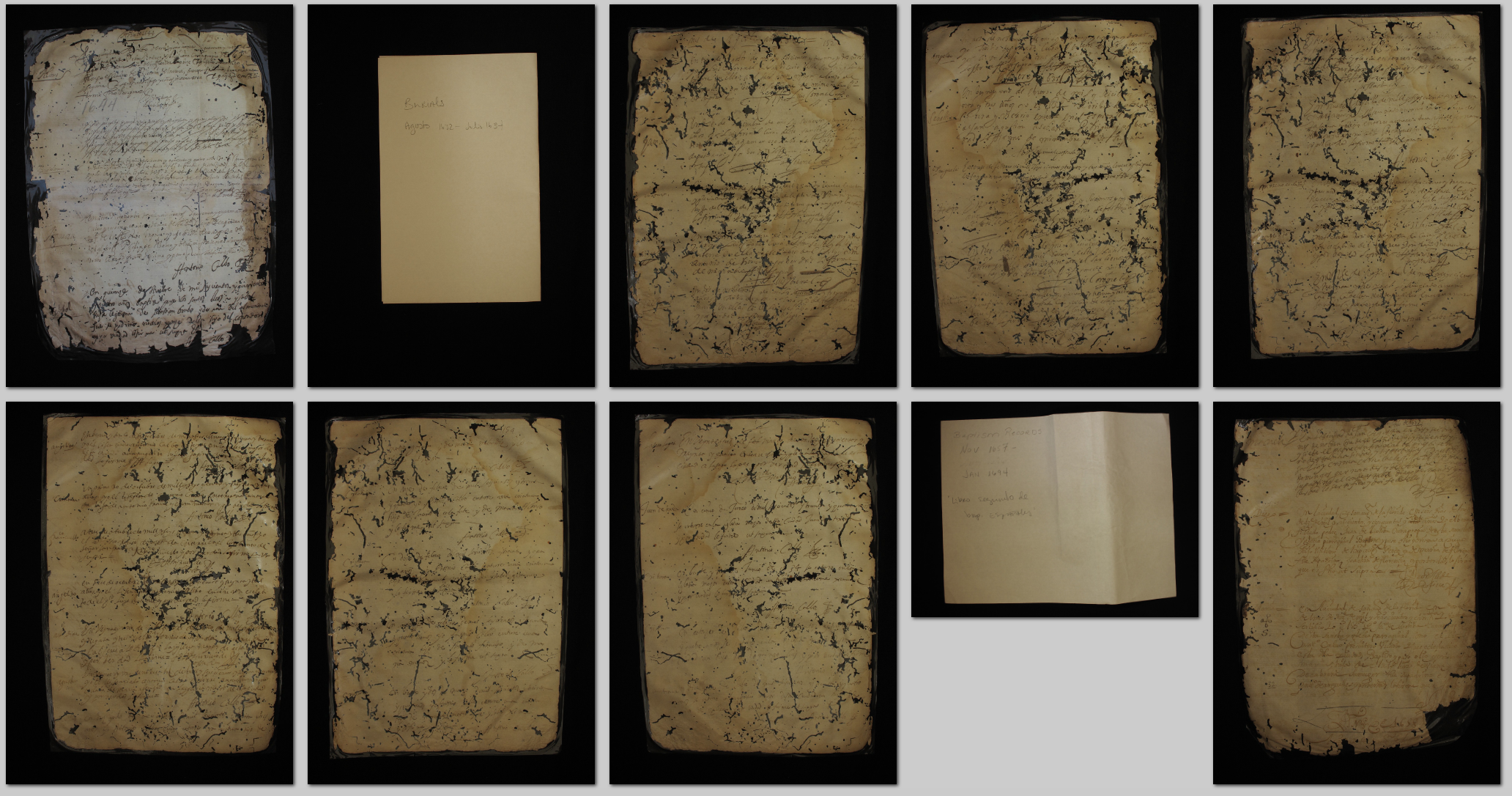

Here at Vanderbilt University, the disintegration and decay of documents is something that is heavily represented in the Slave Societies Digital Archive (SSDA). (Again, check out their collection if you’ve never had the chance!) The SSDA archive is a primer on how digitization can preserve the most fragile of sources. Thinking back to the obituaries Brand speaks of in the opening quote to this blog post, here are images of 17th century burial records from the Archdiocese of St. Augustine, Florida. Thinking through Brand’s poetry helps to not merely see the decaying fibers of paper as purely a loss of information. There are ideas and other factors to consider when looking at documents covered in termite holes or the honeydew of aphids. With respect to Brand we might think of this as the environmental factors of the Caribbean that the digital archive also preserves.

I, myself, am for keeping the bugs because their presence speaks to a once active process of degeneration. The bugs provide answers, even if their pernicious work must come to an end. As the Barbados Mercury and Slave Societies Digital Archive both show, digitization and preservation are necessary for retaining a wide range of cultural knowledge. Ultimately, it is up to individual project teams to decide how to handle the environmental factors of the archives they are processing. But, what causes the archivist the most grief might, in time, be most generative for the poet.